The Journ Al of the Polynesian Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Borobudur 1 Pm

BOROBUDUR SHIP RECONSTRUCTION: DESIGN OUTLINE The intention is to develop a reconstruction of the type of large outrigger vessels depicted at Borobudur in a form suitable for ocean voyaging DISTANCES AND DURATION OF VOYAGES and recreating the first millennium Indonesian voyaging to Madagascar and Africa. Distances: Sunda Strait to Southern Maldives: Approx. 1600 n.m. The vessel should be capable of transporting some Maldives to Northern Madagascar: Approx. 1300 n.m. 25-30 persons, all necessary provisions, stores and a cargo of a few cubic metres volume. Assuming that the voyaging route to Madagascar was via the Maldives, a reasonably swift vessel As far as possible the reconstruction will be built could expect to make each leg of the voyage in using construction techniques from 1st millennium approximately two weeks in the southern winter Southeast Asia: edge-doweled planking, lashings months when good southeasterly winds can be to lugs on the inboard face of planks (tambuku) to expected. However, a period of calm can be secure the frames, and multiple through-beams to experienced at any time of year and provisioning strengthen the hull structure. for three-four weeks would be prudent. The Maldives would provide limited opportunity There are five bas-relief depictions of large vessels for re-provisioning. It can be assumed that rice with outriggers in the galleries of Borobudur. They sufficient for protracted voyaging would be carried are not five depictions of the same vessel. While from Java. the five vessels are obviously similar and may be seen as illustrating a distinct type of vessel there are differences in the clearly observed details. -

Diplomacy and the American Civil War: the Impact on Anglo- American Relations

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses, 2020-current The Graduate School 5-8-2020 Diplomacy and the American Civil War: The impact on Anglo- American relations Johnathan Seitz Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/masters202029 Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Seitz, Johnathan, "Diplomacy and the American Civil War: The impact on Anglo-American relations" (2020). Masters Theses, 2020-current. 56. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/masters202029/56 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses, 2020-current by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Diplomacy and the American Civil War: The Impact on Anglo-American Relations Johnathan Bryant Seitz A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History May 2020 FACULTY COMMITTEE: Committee Chair: Dr. Steven Guerrier Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. David Dillard Dr. John Butt Table of Contents List of Figures..................................................................................................................iii Abstract............................................................................................................................iv Introduction.......................................................................................................................1 -

The Samoan Aidscape: Situated Knowledge and Multiple Realities of Japan’S Foreign Aid to Sāmoa

THE SAMOAN AIDSCAPE: SITUATED KNOWLEDGE AND MULTIPLE REALITIES OF JAPAN’S FOREIGN AID TO SĀMOA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN GEOGRAPHY DECEMBER 2012 By Masami Tsujita Dissertation Committee: Mary G. McDonald, Chairperson Krisnawati Suryanata Murray Chapman John F. Mayer Terence Wesley-Smith © Copyright 2012 By Masami Tsujita ii I would like to dedicate this dissertation to all who work at the forefront of the battle called “development,” believing genuinely that foreign aid can possibly bring better opportunities to people with fewer choices to achieve their life goals and dreams. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is an accumulation of wisdom and support from the people I encountered along the way. My deepest and most humble gratitude extends to my chair and academic advisor of 11 years, Mary G. McDonald. Her patience and consideration, generously given time for intellectual guidance, words of encouragement, and numerous letters of support have sustained me during this long journey. Without Mary as my advisor, I would not have been able to complete this dissertation. I would like to extend my deep appreciation to the rest of my dissertation committee members, Krisnawati Suryanata, Terence Wesley-Smith, Lasei Fepulea‘i John F. Mayer, and Murray Chapman. Thank you, Krisna, for your thought-provoking seminars and insightful comments on my papers. The ways in which you frame the world have greatly helped improved my naïve view of development; Terence, your tangible instructions, constructive critiques, and passion for issues around the development of the Pacific Islands inspired me to study further; John, your openness and reverence for fa‘aSāmoa have been an indispensable source of encouragement for me to continue studying the people and place other than my own; Murray, thank you for your mentoring with detailed instructions to clear confusions and obstacles in becoming a geographer. -

Meroz-Plank Canoe-Edited1 Without Bold Ital

UC Berkeley Survey Reports, Survey of California and Other Indian Languages Title The Plank Canoe of Southern California: Not a Polynesian Import, but a Local Innovation Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1977t6ww Author Meroz, Yoram Publication Date 2013 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Plank Canoe of Southern California: Not a Polynesian Import, but a Local Innovation YORAM MEROZ By nearly a millennium ago, Polynesians had settled most of the habitable islands of the eastern Pacific, as far east as Easter Island and as far north as Hawai‘i, after journeys of thousands of kilometers across open water. It is reasonable to ask whether Polynesian voyagers traveled thousands of kilometers more and reached the Americas. Despite much research and speculation over the past two centuries, evidence of contact between Polynesia and the Americas is scant. At present, it is generally accepted that Polynesians did reach South America, largely on the basis of the presence of the sweet potato, an American cultivar, in prehistoric East Polynesia. More such evidence would be significant and exciting; however, no other argument for such contact is currently free of uncertainty or controversy.1 In a separate debate, archaeologists and ethnologists have been disputing the rise of the unusually complex society of the Chumash of Southern California. Chumash social complexity was closely associated with the development of the plank-built canoe (Hudson et al. 1978), a unique technological and cultural complex, whose origins remain obscure (Gamble 2002). In a recent series of papers, Terry Jones and Kathryn Klar present what they claim is linguistic, archaeological, and ethnographical evidence for prehistoric contact from Polynesia to the Americas (Jones and Klar 2005, Klar and Jones 2005). -

Wao Kele O Puna Comprehensive Management Plan

Wao Kele o Puna Comprehensive Management Plan Prepared for: August, 2017 Prepared by: Nālehualawaku‘ulei Nālehualawaku‘ulei Nā-lehua-lawa-ku‘u-lei is a team of cultural resource specialists and planners that have taken on the responsibilities in preparing this comprehensive management for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. Nā pua o kēia lei nani The flowers of this lovely lei Lehua a‘o Wao Kele The lehua blossoms of Wao Kele Lawa lua i kēia lei Bound tightly in this lei Ku‘u lei makamae My most treasured lei Lei hiwahiwa o Puna Beloved lei of Puna E mālama mākou iā ‘oe Let us serve you E hō mai ka ‘ike Grant us wisdom ‘O mākou nā pua For we represent the flowers O Nālehualawaku‘ulei Of Nālehualawaku‘ulei (Poem by na Auli‘i Mitchell, Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i) We come together like the flowers strung in a lei to complete the task put before us. To assist in the preservation of Hawaiian lands, the sacred lands of Wao Kele o Puna, therefore we are: The Flowers That Complete My Lei Preparation of the Wao Kele o Puna Comprehensive Management Plan In addition to the planning team (Nālehualawaku‘ulei), many minds and hands played important roles in the preparation of this Wao Kele o Puna Comprehensive Management Plan. Likewise, a number of support documents were used in the development of this plan (many are noted as Appendices). As part of the planning process, the Office of Hawaiian Affairs assembled the ‘Aha Kūkā (Advisory Council), bringing members of the diverse Puna community together to provide mana‘o (thoughts and opinions) to OHA regarding the development of this comprehensive management plan (CMP). -

Linguistic Evidence for a Prehistoric Polynesia—Southern California Contact Event

Linguistic Evidence for a Prehistoric Polynesia—Southern California Contact Event KATHRYN A. KLAR University of California, Berkeley TERRY L. JONES California Polytechnic State University Abstract. We describe linguistic evidence for at least one episode of pre- historic contact between Polynesia and Native California, proposing that a borrowed Proto—Central Eastern Polynesian lexical compound was realized as Chumashan tomol ‘plank canoe’ and its dialect variants. Similarly, we suggest that the Gabrielino borrowed two Polynesian forms to designate the ‘sewn- plank canoe’ and ‘boat’ (in general, though probably specifically a dugout). Where the Chumashan form speaks to the material from which plank canoes were made, the Gabrielino forms specifically referred to the techniques (adzing, piercing, sewing). We do not suggest that there is any genetic relationship between Polynesian languages and Chumashan or Gabrielino, only that the linguistic data strongly suggest at least one prehistoric contact event. Introduction. Arguments for prehistoric contact between Polynesia and what is now southern California have been in print since the late nineteenth century when Lang (1877) suggested that the shell fishhooks used by Native Hawaiians and the Chumash of Southern California were so stylistically similar that they had to reflect a shared cultural origin. Later California anthropologists in- cluding the archaeologist Ronald Olson (1930) and the distinguished Alfred Kroeber (1939) suggested that the sewn-plank canoes used by the Chumash and the Gabrielino off the southern California coast were so sophisticated and uni- que for Native America that they likely reflected influence from Polynesia, where plank sewing was common and widespread. However, they adduced no linguistic evidence in support of this hypothesis. -

Dugout Canoe Gr: Prek-2 (Lesson 6)

TRADITIONAL TRANSPORTATION: DUGOUT CANOE GR: PREK-2 (LESSON 6) Elder Quote/Belief: “Summer came and they would go around by boat. They made their first dugout canoes. They chopped down large cottonwood, and fashioned that into a canoe. They went in that into Eyak Lake. Then they tried spruce instead of cotton wood. That too was good. They carved large boats out of spruce.” -Anna Nelson Harry 1 Anna Nelson Harry, Yakutat, about 1975. (Photo courtesy of Richard Dauenhauer) Grade Level: PreK-2 Overview: The Eyak and Sugpiaq people traditionally carved dugout canoes in the Chugach Region, specifically in Prince William Sound. “The canoes were so seaworthy that they were used not just for interisland voyages to visit relatives or allies, but also to wage war and to engage in trade missions over hundreds of miles. In fact, dugout canoes plied the waters between Southeast Alaska, (Eyak) and Kodiak Island in the days before the coming of Europeans”. (Echo’s http://www.echospace.org/articles/273/sections/665.html) Standards: AK Cultural: AK Content Science: CRCC: E4: Culturally-knowledgeable students B2: A student should understand and MC1: Different kinds of wood have demonstrate an awareness and be able to apply the concepts, models, different qualities and different uses; appreciation of the relationships and theories, universal principles, and facts wood can be obtained from the forest processes of interaction of all elements in that explain the physical world. and from driftwood. the world around them. A student should determine how ideas and concepts from one knowledge system relate to those derived from another knowledge system. -

Disability, Activism, and Education in Samoa, 1970-1980

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE December 2015 Trying Times: Disability, Activism, and Education in Samoa, 1970-1980 Juliann Anesi Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Anesi, Juliann, "Trying Times: Disability, Activism, and Education in Samoa, 1970-1980" (2015). Dissertations - ALL. 418. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/418 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract In the 1970s and 1980s, Samoan women organizers established Aoga Fiamalamalama and Loto Taumafai, which were educational institutions in Samoa, an island in the Pacific. Establishing these schools for students with intellectual and physical disabilities, excluded from attending formal schools based on the misconception that they were "uneducable". In this project, I seek to understand how parent advocates, allies, teachers, women organizers, women with disabilities, and former students of these schools understood disability, illness, inclusive education, and community organizing. Through interviews and analysis of archival documents, stories, cultural myths, legends related to people with disabilities, pamphlets, and newspaper media, I examine how disability advocates and people with disabilities interact with educational and cultural discourses to shape programs for the empowerment of people with disabilities. I argue that the notions of ma’i (sickness), activism, and disability inform the Samoan context, and by understanding, their influence on human rights and educational policies can inform our biased attitudes on ableism and normalcy. -

Chapter 5. Social and Economic Environment 5.1 Cultural Resources

Rose Atoll National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan Chapter 5. Social and Economic Environment 5.1 Cultural Resources Archaeological and other cultural resources are important components of our nation’s heritage. The Service is committed to protecting valuable evidence of plant, animal, and human interactions with each other and the landscape over time. These may include previously recorded or yet undocumented historic, cultural, archaeological, and paleontological resources as well as traditional cultural properties and the historic built environment. Protection of cultural resources is legally mandated under numerous Federal laws and regulations. Foremost among these are the NHPA, as amended, the Antiquities Act, Historic Sites Act, Archaeological Resources Protection Act, as amended, and Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. Additionally, the Refuge seeks to maintain a working relationship and consult on a regular basis with villages that are or were traditionally tied to Rose Atoll. 5.1.1 Historical Background The seafaring Polynesians settled the Samoan Archipelago about 3,000 years ago. They are thought to have been from Southeast Asia, making their way through Melanesia and Fiji to Samoa and Tonga. They brought with them plants, pigs, dogs, chickens, and likely the Polynesian rat. Most settlement occurred in coastal areas and other islands, resulting in archaeological sites lost to ocean waters. Early archaeological sites housed pottery, basalt flakes and tools, volcanic glass, shell fishhooks and ornaments, and faunal remains. Stone quarries (used for tools such as adzes) have also been discovered on Tutuila and basalt from Tutuila has been found on the Manu’a Islands. Grinding stones have also been found in the Manu’a Islands. -

Granting Samoans American Citizenship While Protecting Samoan Land and Culture

MCCLOSKEY, 10 DREXEL L. REV. 497.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 5/14/18 2:11 PM GRANTING SAMOANS AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP WHILE PROTECTING SAMOAN LAND AND CULTURE Brendan McCloskey* ABSTRACT American Samoa is the only inhabited U.S. territory that does not have birthright American citizenship. Having birthright American citizenship is an important privilege because it bestows upon individ- uals the full protections of the U.S. Constitution, as well as many other benefits to which U.S. citizens are entitled. Despite the fact that American Samoa has been part of the United States for approximately 118 years, and the fact that American citizenship is granted automat- ically at birth in every other inhabited U.S. territory, American Sa- moans are designated the inferior quasi-status of U.S. National. In 2013, several native Samoans brought suit in federal court argu- ing for official recognition of birthright American citizenship in American Samoa. In Tuaua v. United States, the U.S. Court of Ap- peals for the D.C. Circuit affirmed a district court decision that denied Samoans recognition as American citizens. In its opinion, the court cited the Territorial Incorporation Doctrine from the Insular Cases and held that implementation of citizenship status in Samoa would be “impractical and anomalous” based on the lack of consensus among the Samoan people and the democratically elected government. In its reasoning, the court also cited the possible threat that citizenship sta- tus could pose to Samoan culture, specifically the territory’s commu- nal land system. In June 2016, the Supreme Court denied certiorari, thereby allowing the D.C. -

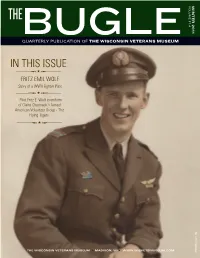

In This Issue

VOLUME 17:4 2011 WINTER IN THIS ISSUE FRITZ EMIL WOLF Story of a WWII Fighter Pilot Pilot Fritz E. Wolf in uniform of Claire Chennault’s famed American Volunteer Group - The Flying Tigers. THE WISCONSIN VETERANS MUSEUM MADISON, WI WWW.WISVETSMUSEUM.COM WVM Mss 2011.102 FROM THE DIRECTOR Wisconsin Veterans Museum. How soldier in the 7th Wisconsin. He may could it be otherwise? We are sur- have read about the Iron Brigade rounded by things that resonate in books, but the idea of advancing with stories of Wisconsin’s veterans. shoulder to shoulder in line of battle In this issue you will read stories under musket and cannon fire was about three men who, although sep- a relic of a far away past. Likewise, arated by time, embody commonly Hunt could never have imagined held traits that link them together Wolf’s airplane, let alone land- among a long line of veterans. We ing one on the deck of a ship. As a start with the account of the in- resident of Kenosha, Isermann may trepid naval combat flying ace Fritz have known veterans of Hunt’s Iron Wolf, a native of Madison by way of Brigade, but their ancient exploits Shawano, Wisconsin who flew with were long ago events separated by Claire Chennault’s Flying Tigers in more than fifty years from the Great China, and later with the US Navy. War. To a twentieth century man Wolf’s story is followed by the tragic engaged in WWI naval operations, account of an English immigrant, Gettysburg might as well have been John Hunt, who settled in Wiscon- Thermopylae. -

In the Supreme Court of the United States

No. 15-981 In the Supreme Court of the United States LENEUOTI FIAFIA TUAUA, ET AL., PETITIONERS v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ET AL. ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT BRIEF FOR THE FEDERAL RESPONDENTS IN OPPOSITION DONALD B. VERRILLI, JR. Solicitor General Counsel of Record BENJAMIN C. MIZER Principal Deputy Assistant Attorney General MARK B. STERN PATRICK G. NEMEROFF Attorneys Department of Justice Washington, D.C. 20530-0001 [email protected] (202) 514-2217 QUESTION PRESENTED Whether the Fourteenth Amendment’s Citizenship Clause, which provides that “[a]ll persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States,” U.S. Const. Amend. XIV, § 1, Cl. 1, confers United States citizenship on individuals born in American Samoa. (I) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Opinions below .............................................................................. 1 Jurisdiction .................................................................................... 1 Statement ...................................................................................... 2 Argument ....................................................................................... 8 Conclusion ................................................................................... 22 TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Cases: Afroyim v. Rusk, 387 U.S. 253 (1967) ................................. 20 Armstrong v. United States, 182 U.S. 243 (1901) .............