Phad of the Phad : Reading and Writing of the Ritual Craft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

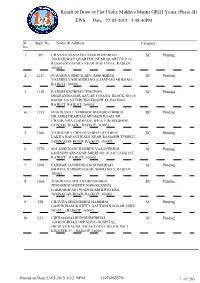

EWS 22-05-2015 5:48:40PM Result of Draw of Flat Under Mukhya Mantri

Result of Draw of Flat Under Mukhya Mantri GRIH Yojna (Phase-II) EWS Date : 22-05-2015 5:48:40PM Sr. Appl. No. Name & Address Category No. 1 99 CHAVDA SANJAYKUMAR PITHABHAI SC Pending 560 RAILWAY QUARTER, NEAR QUARTER P 14, RUKHADIYAPARA NEAR MAFATIYA, RAJKOT, 360002 2 1117 PURABIYA SIMPALBEN ASHOKBHAI SC Pending VALMIKI VADI SHERI NO 4, JAMNAGAR ROAD, , RAJKOT, 360001 3 1119 RAJESH NAJIBHAI CHAUHAN SC Pending DHARAMNAGAR AAVAS YOJANA, BLOCK NO 10 ROOM 286 SATERLING HOSPITAL PACHAD, RAJKOT, RAJKOT, 360001 4 1155 MAKWANA LAXMIBEN BHAGIRATHBHAI SC Pending DR AMBEDKARNAGAR MAIN ROAD, NR CHAMUNDA GARRAGE, B\H S T WORKSHOP, GONDAL ROAD, , RAJKOT, 360001 5 1160 VADODARA CHHAGANBHAI JIVABHAI SC Pending LAKHA BAPANI WADI, NEAR RAMAPIR TEMPLE, JAMNAGAR ROAD, RAJKOT, 360002 6 1279 SOLANKI KANCHANBEN VASANTBHAI SC Pending KHOADIYARNAGAR SHERI NO 18 AJI VASAHAT, RAJKOT, , RAJKOT, 360003 7 1309 PARMAR JAGDISHBHAI SOMABHAI SC Pending BH RTO, NARSHINAGAR, SHERI NO 5, RAJKOT, 360001 8 1364 MAKWANA MILAN BHANUBHAI SC Pending JUMABHAI MISTRY NAMAKANMA, LAKHABAPANI WADI SLAM KWATERS, JAMNAGAR ROAD, RAJKOT, 360001 9 528 CHAVDA SHAMJIBHAI HAJIBHAI SC Pending GADHIGRAM SOCIETY GAUTAM NAGAAR SARY NO 02, , , RAJKOT, 360001 10 531 CHUDASMA DILIP BHIMJIBHAI SC Pending 150 RINGROAD OPP SLING HOSPITAL, DHARAMNAGAR AWAS YOJNA BLOCK NO 1 KWATER-17, , RAJKOT, 360001 Printed on Date 22-05-2015 6:12:19PM 139769655791 1 of 203 Result of Draw of Flat Under Mukhya Mantri GRIH Yojna (Phase-II) EWS Date : 22-05-2015 5:48:40PM Sr. Appl. No. Name & Address Category No. 11 532 -

Arts a LIVING TEMPLE - (PHAD PAINTING in RAJASTHAN)

[Mahawar *, Vol.6 (Iss.3): March, 2018] ISSN- 2350-0530(O), ISSN- c2394-3629(P) (Received: Feb 01, 2018 - Accepted: Mar 22, 2018) DOI: 10.29121/granthaalayah.v6.i3.2018.1521 Arts A LIVING TEMPLE - (PHAD PAINTING IN RAJASTHAN) Dr. Krishna Mahawar *1 *1 Assistance Professor (Painting), Rajasthan University, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India Abstract I consider Phad Painting as a valuable pilgrimage of Rajasthan. Phad painting (Mewar Style of painting) or Phad is a stye religious scroll painting and folk painting, practiced in Rajasthan state of India. This is a unique scroll making folk art; this style of painting is traditionally done on a long piece of cloth or canvas, known as phad. It is synonymous with the Bhopa community of the state. These are beautiful specimen of the Rajasthani cloth paintings. The narratives of the folk deities of Rajasthan, mostly of Pabuji and Devnarayan- who are worshipped as the incarnation of lord Vishnu & Laxman. Each hero-god has a different performer-priest or Bhopa. The repertoire of the bhopas consists of epics of some of the popular local hero-gods such as Pabuji, Devji, Tejaji, Gogaji, Ramdevji.The Phad also depict the lives of Ramdev Ji, Rama, Krishna, Budhha & Mahaveera. The iconography of these forms has evolved in a distinctive way. Shahpura in Bhilwara district of Rajasthan are widely known as the traditional artists of this folk art-form for the last two centuries. Presently, Shree Lal Joshi, Nand Kishor Joshi, Prakash Joshi and Shanti Lal Joshi are the most noted artists of the phad painting, who are known for their innovations and creativity. -

Phad Painting of Bhilwara, Rajasthan

A Review AJHSAsian Journal of Home Science Volume 8 | Issue 2 | December, 2013 | 746-749 Phad painting of Bhilwara, Rajasthan RUPALI RAJVANSHI AND MEENU SRIVASTAVA Received:30.05.2012; Accepted:24.10.2013 See end of the paper for authors’ affiliations Correspondence to : RUPALI RAJVANSHI Department of Textile and Apparel Designing, College of Home Science, Maharana Pratap KEY WORDS : Phad painting University of Agriculture and Technology, UDAIPUR HOWTO CITE THIS PAPER : Rajvanshi, Rupali and Srivastava, Meenu (2013). Phad painting of Bhilwara, Rajasthan. Asian J. (RAJASTHAN) INDIA Home Sci., 8 (2): 746-749. had painting is a beautiful specimen of Indian cloth The main theme of Phad painting was to illustrate the painting which has its origin in Rajasthan. The Phad heroes of Goga Chuhan, Prithviraj Chauhan, Amar Singh Ppaintings of Rajasthan are basically the cloth painting Rathore, Teja ji and many others were illustrated on the Phadas which is done on scroll of cloth known as “Phad”. in the earlier times but today the stories from the life of Pabuji The Rajasthani Phad (sometimes spelled Par) is a visual and Narayandevji are primarily depicted. While, Phadas display accompaniment to a ceremony involving the singing and the stories of Ram Krishnadala, Bhainsasura and Ramdev. recitation of the deeds of folk hero deities in Rajasthan, a The legends are painted on long rectangular cloths that desert state in the west of india. Phad painting is a type of may be 35 feet long by 5 feet wide for Devnarayan Phad and scroll painting. The smaller version of Phad painting is called 15 feet by 5 feet for Pabuji-ki Phad (Fig. -

Conserving Water & Biodiversity: Traditions of Sacred Groves in India

European Journal of Sustainable Development (2016), 5, 4, 129-140 ISSN: 2239-5938 Doi: 10.14207/ejsd.2016.v5n4p129 Conserving Water & Biodiversity: Traditions of Sacred Groves in India Mala Agarwal1 Abstract Sacred groves, a wide spread phenomenon in cultures across the world, are often associated with religion & culture, are instrumental in preserving biodiversity and nature without being questioned. Scattered all over India e.g. scrub forests in the Thar Desert of Rajasthan maintained by the Bishnois, Hariyali in Uttarakhand, Shinpin in Himachal Pradesh and associated with religion they are often sacrosanct. The sacred groves are self sustained ecosystem and conserve the endemic, endangered & threatened species, medicinal plants and wide variety of cultivars. Water and soil conservation is the most well documented ecological service provided by the sacred groves that helps prevent flash floods and ensures supply of water in lean season in the desert of Rajasthan. Encountering threats like fragmentation, urbanization, and overexploitation now they need governmental support to exist e.g. Introduction of the ‘Protected Area Category Community Reserves’ under the Wild Life (Protection) Amendment Act, 2002. Key words-Water conservation, eco-system, bio diversity, sacred groves. 1. Introduction Sacred Groves are considered as “Sacred Natural Sites” (IUCN) [1].These are the relic forest patches preserved in the name of religion & culture. They extend from Asia, Africa, and Europe to America mostly in Africa and Asia [2]. In India, Groves are present from North-east Himalayan region, Western & Eastern Ghats, Coastal region, Central Indian Plateau and Western desert [3]. Indian sacred groves have pre-Vedic origin. They are associated with indigenous / tribal communities who believe in divinity of nature and natural resources. -

Interview List for Selection of Appointment of Notaries in the State of Rajasthan

Interview List for Selection of Appointment of Notaries in the State of Rajasthan Area of Practice S.No Name File No. Father Name Address Enrollment no. Applied for Behind the Petrol Pump Taranagar, Dist. N-11013/592/2016- Nanakram Rajgarh Road Taranagar R/344/1998 1 Madan Singh Sahu Churu NC Sahu Dist.Churu Rajasthan- Dt.13.04.98 331304 VPO Gaju Was Tehsil Taranagar, Dist. N-11013/593/2016- R/239/2002 2 Shiv Chand Ram Mahipat Ram Taranagar, Distt.Churu Churu NC Dt.24.02.02 Rajasthan-331304 Opp.Govt.Jawahar N-11013/594/2016- P.S.School Kuchaman R/1296/2003 3 Madan Lal Kunhar Kuchaman City Hanuman Ram NC City Nagar Rajasthan- Dt.31.08.03 341508 Ward No.11, Padampur, Bhupender Singh Padampur, Sri N-11013/595/2016- Nirmal Singh R/2384/2004 4 Distt. Sri Ganganagar , Brar Ganganagar NC Brar Dt.02.10.04 Rajasthan-335041 Brijendra Singh N-11013/596/2016- Lt.Sh.Johar Lal A-89, J.P. Colony, Jaipur, 5 Rajasthan R/ Meena NC Meena Rajasthan 3-R-22, Prabhat Nagar, Dt. & Sess. Court N-11013/597/2016- Lt.Sh.Himatlalj Hiran Magri, Sector-5, R/2185/2001 6 Om Prakash Shrimali Udaipur NC i Shrimali dave Udaipur, Rajasthan- Dt.07.12.01 313002 Sawai Madhopur C-8, Keshav Nagar, N-11013/598/2016- Mool Chand R/432/1983 7 Shiv Charan Lal Soni (only one Mantown, Sawai NC Soni Dt.12.09.83 memorial ) Madhopur, Rajasthan Kakarh- Kunj New City N-11013/599/2016- R/1798/2001 8 Pramod Sharma Kishangarh, Ajmer Ramnivas Kisangarh Ajmer NC Dt.15.09.01 Rajasthan-305802 414, Sector 4, Santosh Kumar Distt. -

Certificate Course in Criminology (Private) S

Sardar Patel University of Police, Security and Criminal Justice, Jodhpur Provisional Short Listed Candidates of Certificate Course in Criminology (Private) S. No. E-mail Address Applicant's Name Father's Name 1 thes***[email protected] AADESH KUMAR SEN BHANWAR LAL SEN 2 rai***[email protected] AADRAM HARU RAM 3 aaja***[email protected] aajam jalawat mangu khan 4 shar***[email protected] ABHAY KUMAR ANANT KUMAR 5 abha***[email protected] ABHAY KUMAR NARENDRA SINGH 6 abha***[email protected] abhay singh poonam chand 7 stay***[email protected] ABHAY SINGH SITA RAM 8 as77***[email protected] ABHIMANYU CHAUHAN PRATAP SINGH CHAUHAN 9 abhi***[email protected] ABHISHEK ASHOK KUMAR 10 rega***[email protected] ABHISHEK KUMAR KASOTIYA LAL CHAND KASOTIYA 11 para***[email protected] ABHISHEK PARASAR GOPAL PARASAR 12 shar***[email protected] abhishek sharma siya ram sharma 13 abhi***[email protected] Abhishek Singh Parbat Singh 14 ades***[email protected] ADESH NEHRA SURESH NEHRA 15 adit***[email protected] ADITYA ACHARYA RAJESH ACHARYA 16 aelc***[email protected] AELCHI BAI POONAMARAM 17 ajay***[email protected] AJAY KUMAR DHARANA PARAMANAND DHARANA 18 ajay***[email protected] AJAY KUMAR SAINI KALLU RAM SAINI 19 as30***[email protected] AJAY KUMAR SAINI RAM BHAROSI SAINI 20 ajay***[email protected] AJAY NAIN VIJAY KUMAR 21 ajay***[email protected] AJAY POONIYA JAGDISH POONIYA 22 KOMA***[email protected] AJAY SINGH DEVI SINGH 23 akha***[email protected] AJAY SINGH KHANGAROT RAJPAL SINGH KHANGAROT 24 ajay***[email protected] -

Modified Mining Plan with Progressive Mine Closure

Category of Mine- OTFM- OC MODIFIED MINING PLAN WITH PROGRESSIVE MINE CLOSURE PLAN OF BHACHERIYA QUARTZ, FELDSPAR MICA & GRANITE MINE (Submitted as per rule Minor mineral rule 29 [5 (vi)] & (7) of RMMCR-2017 for working lease) BHACHERIYA QUARTZ, FELDSPAR, MICA & GRANITE MINE MINERALs – QUARTZ, FELDSPAR, MICA & GRANITE, M.L. No.- 18/2001 NEAR VILLAGE– BHACHERIYA TEHSIL – DEOGARH, DISTRICT – RAJSAMAND (RAJ.) LEASE AREA – 4.8180 HECT. (NON FOREST LAND) SSO ID- AURUMGRANITE LEASE PERIOD FROM 09. 10. 2007 TO 08. 10. 2057 Period of Mining scheme with progressive mine closure plan start from 2018-2019 to 2021-2022 [ LESSEE ] M/s Aurum Granite R/o- Village-Bhachediya,Post-Kundwa, Tehsil- Deogarh, Distt.Rajsamand(Raj.) Mobile no.- 95898-59311 E-mail- [email protected] PREPARED BY DR. MUKESH KUMAR JAGETIA C/o ARAVALLI GEOLOGICAL & MINING CONSULTANCY 24, Shopping Center, Opposite Mining Office, Hiran Magri Sector-11, Udaipur-313002 (Rajasthan) Phone No. - 0294-2489840, Mobile No.-9414290241, 9983325026 Email id- [email protected], [email protected] IBM RQP Registration No.-RQP/UDP/189/99-A RQP certificate valid upto 26-08-2021 File no: agmc/Amt 313 CONTENTS S. No. Chapter Particulars Page No. No. 1. General & introduction 1 2. Location & accessibility 4 3. Details of approved mining plan/scheme of mining 6 (if any) PART - A 4. 1.0 Geology and exploration 9-29 5. 2.0 Mining 30-44 6. 3.0 Mine drainage 46 7. 4.0 Stacking of mineral, reject/ sub grade 47 material and disposal of waste 8. 5.0 Use of mineral 49 9. 6.0 Processing of ROM and mineral reject 52 10. -

Los Angeles a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomu

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles FIND THE TRUE COUNTRY: DEVOTIONAL MUSIC AND THE SELF IN INDIA’S NATIONAL CULTURE A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by VIVEK VIRANI 2016 © Copyright by Vivek Virani 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Find the True Country: Devotional Music and the Self in India’s National Culture by Vivek Virani Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Daniel M. Neuman, Chair For centuries, the songs of devotional poet-saints have been an integral part of Indian religious life. Countless regional traditions of bhajans (devotional songs) have been able to maintain their existence by adapting to serve the contemporary social needs of their participants. This dissertation draws on fieldwork conducted over 2014-2015 with contemporary bhajan performers from many different genres and styles throughout India. It highlights a specific tradition in the Central Indian region of Malwa based on poetry by Kabir and other Sants (anti- establishment poet-saints) performed by lower-caste singers. This tradition was largely unheard- of half a century ago, but is now a major part of Malwa’s cultural life that has facilitated the creation of lower-caste spiritual networks and created a space for those networks to engage in discourse about social issues. Malwa’s bhajan singers have also become part of India’s popular ii religious and musical life as certain performers have attained celebrity status and been recognized at the national level as living bearers of the Sant tradition. This dissertation follows performers and songs from Malwa into new contexts and explores the processes by which performers and audiences in diverse styles and contexts use Sant bhajans to construct understandings of the self. -

2018 NIC BALLIA 8-10-18 (5128).Xlsx

DPR for Ballia, ULB– Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana BLC-(N) (Urban) 2018 WARD S.N CANDIDATE NAME Caste F/H NAME AGE NO. ADDRESS 1 03 AAASHIM KHATOON 4 MAIHARDDIN KURAISHI 43 KAZIPURA ISALAMABAD BALLIA 2 15 AAYASH KHATOON 4 SAKIL AHAMAD 25 RAJENDRA NAGAR ,BALLIA 3 03 ABDUL GAFFAR ANSARI 4 NABBI RASUL 64 KASABTOLA KAJIPURA BALLIA 4 03 ABDUL MAJID 4 ABDUL SAKUR 38 KAZIPURA ISALAMABAD BALLIA 5 03 ABDUL RAHEEM 4 NABI RASOOL 50 KASABTOLA KAJIPURA BALLIA 6 14 ABHAY KUMAR 4 JAYRAM 28 RAJPUT NEWARI,BALLIA 7 11 ABHAY KUMAR YADAV 4 VIJAYMAL YADAV 35 MUHAMMADPUR BALLIA 8 13 ABHISHEK KUUMAR SINGH 4 KASHI NATH SINGH 35 TAIGORE NAGAR JEL KE PEECHE 9 11 ADITYA PRASAD KANU 4 VISHWANATH 66 GANDHI NAGAR CHITBARAGAON 10 11 AFASANA KHATOON 1 YUNUSH ANSHARI 26 BAHERI BALLIA 11 03 AFROJ ALI ANSARI 4 MOHAMMAD GAFFAR 37 KAZIPURA ISALAMABAD BALLIA 12 16 AFTAB ALAM 4 MD. HABIB 45 RAJPUT NEWARI BALLIA 13 03 AJAM KURAISHI 4 HASIM KURASHI 53 KAZIPURA ISALAMABAD BALLIA 14 13 AJAY KUMAR KHARWAR 1 HAR RAM KHARWAR 18 RAMPUR UDDYABHAN NAI BASTI BALLA 15 11 AJAY KUMAR YADAV 4 RAM VILASH YADAV 36 VAJEERAPUR CHANDANPUR BALLIA 16 07 AJAY PASWAN 1 BHARAT PASWAN 31 PURANI BASTI 17 11 AJAY PASWAN 1 SHIV NATH RAM 21 KRISHNA NAGAR, BALLIA 18 11 AJAY YADAV 4 DOMAN YADAV 45 KRISHNA NAGAR KANSHPUR BALLIA 19 13 AJEET KUMAR 4 HARERAM PRASAD 34 RAMPUR UDDYABHAN NAI BASTI BALLA 20 11 AJEET YADAV 4 PARSHURAM YADAV 34 JAPLINGANJ YADAV NAGAR BALLIA 21 03 AKHTAR ALI ANSARI 1 MD JABBAR ASNARI 35 KAZIPURA ISALAMABAD BALLIA 22 03 AKHTAR ALI ANSARI 1 NURUL HASAN 59 KAZIPURA ISLAMABAD BALLILA 23 AKHTARI -

CSC E Governance Services Ltd

CSC e_Governance Services Ltd. Sr.No Agent Name Agent Address Dist name State name Pincode 1 Aayuesh Goel Kalsi Road Dakpathar Vikasnagar Dehradun Dehradun Uttarakhand 248125 Gandhi Bomma Center Road, Beside Vro Office, Alamuru, East 2 Achanta Srinivasarao East Godavari Andhra Pradesh 533233 Godavari, Ap 3 Ajay Joshi Pitgara, Badnawar, Dist. Dhar Dhar Madhya Pradesh 454660 4 Ajay Kumar Noukri Point, Rani Bajaar,Nohar Hanumangarh Rajasthan 335523 5 Akhilesh Thakur Court Road Dhar Dhar Madhya Pradesh 454446 4-125, Gandhi Center, Paritala, Kanchikacherla, Krishna, Andhra 6 Akula Narasimhaswamy Krishna Andhra Pradesh 521180 Pradesh 7 Anil Kumar Manjeri Csc Center,Poonthottathil Tower Nilambur Road Manjeri Malappuram Kerala 676121 8 Anil Namta Yashmehul Studio,Bagbera Colony J.P. Road East Singhbhum Jharkhand 831002 9 Ankit Saini Sarthak Computer Education Holi Tiba Tijara Alwar Rajasthan 301411 10 Arvind Madan Teli Near Bus Stand, Jalgaon Road, Jamner, Jalgaon Jalgaon Maharashtra 424206 11 Aziz Gohar Khan Tareen Vill Thapal, Najibabad Distt Bijnor Up Bijnor Uttar Pradesh 246763 12 Balwinder Singh Near Sub Tehsil, Alal Road Sherpur Sangrur Punjab 148025 13 Basavaraj Hiremath Maheshwar Digital,509, Main Road Pathade Galli Akkol-591211 Belgaum Karnataka 591211 14 Bhera Ram Prime Computers Opp. Rajasthan Marudhar Bank Bilara Jodhpur Jodhpur Rajasthan 342602 15 Chekka Suresh Kumar 7-135 Main Road Opp Sbi Rayavaram, East Godavari, Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Andhra Pradesh 533346 16 Chitikesu Harisuman H No 8-1-70 ,Opp.Mamatha Hospital , Jammikunta -

-

Mp History, Art & Culture

MADHYA PRADESH HISTORY & CULTURE (UPDATED DECEMBER 2020) MPPSC 2020 Web: mppscadda.com Telegram: t.me/mppscadda WhatsApp/Call: 9953733830, 7982862964 MADHYA PRADESH: HISTORY & CULTURE CONTENTS ❖ Chapter 1 MAJOR EVENTS AND DYNASTIES IN THE HISTORY OF MADHYA PRADESH ❖ Chapter 2 CONTRIBUTION OF MADHYA PRADESH IN FREEDOM MOVEMENT ❖ Chapter 3 MAJOR TRIBES OF MADHYA PRADESH ❖ Chapter 4 IMPORTANT TRIBAL PERSONALITIES OF MADHYA PRADESH ❖ Chapter 5 MAJOR FESTIVALS and FAIRS of MADHYA PRADESH ❖ Chapter 6 MAJOR FOLK MUSIC, FOLK ARTS &FOLK THEATRE OF MADHYA PRADESH ❖ Chapter 7 MAJOR DIALECTS OF MADHYA PRADESH ❖ Chapter 8 MAJOR ARTS AND SCULPTURE OF MADHYA PRADESH ❖ Chapter 9 RELIGIOUS AND TOURIST PLACES OF MADHYA PRADESH ❖ Chapter 10 LITERATURE and LITTERATEUR OF MADHYA PRADESH ❖ Chapter 11 FAMOUS MUSICIANS AND PAINTERS OF MADHYA PRADESH ❖ Chapter 12 CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS OF MADHYA PRADESH ❖ Chapter 13 MAJOR AWARDS and HONOURS OF MADHYA PRADESH Web: mppscadda.com Telegram: t.me/mppscadda WhatsApp/Call: 9953733830, 7982862964 MPPSC 2020 PRELIMS NOTES MADHYA PRADESH HISTORY & CULTURE Major Events and Dynasties in the History of Madhya Pradesh MPPSCADDA Web: mppscadda.com Telegram: t.me/mppscadda WhatsApp/Call: 9953733830, 7982862964 1. MAJOR EVENTS AND MAJOR DYNASTIES IN HISTORY OF MADHYA PRADESH ANCIENT HISTORY OF MP MADHYA PRADESH • As its name implies—madhya means "central" and pradesh means "region" or "state"—it is situated in the heart of the country. • This central region belongs to the Gondwana land the southern part of supercontinent pangea. The term Gondwana means the land of the Gonds and even today, MP continues to be inhabited by various tribal groups Prehistoric Period of Madhya Pradesh • The prehistoric settlements in present day MP developed primarily in the valleys of rivers such as Narmada, Chambal and Betwa.