559188 Bk Harbison US

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Association for Jewish Studies

42ND ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE ASSOCIATION FOR JEWISH STUDIES DECEMBER 19– 21, 2010 WESTIN COPLEY PLACE BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS ASSOCIATION FOR JEWISH STUDIES C/O CENTER FOR JEWISH HISTORY 15 WEST 16TH STREET NEW YORK, NY 10011-6301 PHONE: (917) 606-8249 FAX: (917) 606-8222 E-MAIL: [email protected] www.ajsnet.org President AJS Staff Marsha Rozenblit, University of Maryland Rona Sheramy, Executive Director Vice President/Membership Karen Terry, Program and Membership and Outreach Coordinator Anita Norich, University of Michigan Natasha Perlis, Project Manager Vice President/Program Emma Barker, Conference and Program Derek Penslar, University of Toronto Associate Vice President/Publications Karin Kugel, Program Book Designer and Jeffrey Shandler, Rutgers University Webmaster Secretary/Treasurer Graphic Designer, Cover Jonathan Sarna, Brandeis University Ellen Nygaard The Association for Jewish Studies is a Constituent Society of The American Council of Learned Societies. The Association for Jewish Studies wishes to thank the Center for Jewish History and its constituent organizations—the American Jewish Historical Society, the American Sephardi Federation, the Leo Baeck Institute, the Yeshiva University Museum, and the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research— for providing the AJS with offi ce space at the Center for Jewish History. Cover credit: “Israelitish Synagogue, Warren Street,” in the Boston Almanac, 1854. American Jewish Historical Society, Boston, MA and New York, NY. Copyright © 2010 No portion of this publication may be reproduced by any means without the express written permission of the Association for Jewish Studies. The views expressed in advertisements herein are those of the advertisers and do not necessarily refl ect those of the Association for Jewish Studies. -

Jascha Nemtsov• “The Scandal Was Perfect”

Jascha Nemtsov “The Scandal Was Perfect” Jewish Music in the Works of European Composers Well into the 19th century, Jewish music went largely unnoticed in Euro- pean culture or was treated dismissively. Russian composers wrote the first chapter of musical Judaica. At the start of the 20th century, a Jewish national school of music was established in Russia; this school later in- fluenced the work of many composers in Western Europe. Since the Holocaust, Jewish music is understood less as folk music, it has become a political and moral symbol. The parties of the Hasidim where they merrily discourse on talmudic problems. If the entertainment runs down or if some- one does not take part, they make up for it by singing. Melodies are invented... a wonder-rabbi... suddenly laid his face on his arms, which were resting on the table, and remained in that position for three hours while everyone was silent. When he awoke he wept and sang an entirely new, gay, military march. Franz Kafka, 29 November 19111 What particularly impressed Kafka at a gathering of a Hasidic community at their rabbi’s home is typical for traditional Judaism: Religion and music are so tightly intertwined that reading and praying are conducted only in song. The first Hebrew grammar, De accentibus et orthographia linguae Hebraicae, by the Stuttgart humanist Johannes Reuchlin (1455–1522), was published in Alsatian Ha- genau in 1518. Reuchlin focused on the Hebrew Bible and included as well the motifs – Biblical cantillations – with which it was chanted by the European (Ashkenazi) Jews. This marked the first appearance of these motifs outside the Jewish community as well as the first time that they were transcribed into European musical notation.2 Music that had hitherto fulfilled only a ritual purpose thus became the subject of aca- demic discourse. -

Piano Trio Repertoire Discography & Review Index: "S” Composers Compiled by David Barker

An A to Z of the Piano Trio Repertoire Discography & Review Index: "S” Composers Compiled by David Barker Project Index Kaija Saariaho Caecilian Trio 1952-, Finland (+ Fauré, Lalo 1, Ravel; Debussy, Fauré, Ravel & Roussel: String quartets, Ravel: Violin Je sens un deuxième coeur (2003) sonata) Vox CD3X3031 (+ Sibelius 2-4; Lefkowitz: Ruminations, Schissi: Nene, Wennakoski: Paarme) Trio Daphnis Yarlung Records YAR52638 [review] (+ Trio 2) UT3 Records UT3009 Leonid Sabaneev Florestan Trio 1881-1968, Russia (+ Trio 2) Hyperion CDA67538 [review][review] Trio-Impromptu (1907) Göbel Trio Berlin Michael Schäfer, Ilona Then-Bergh, Wen-Sinn SWR Music SWR10379 Yang (+ Sonata) Golub-Kaplan-Carr Trio Genuin GEN12236 [review] (+ Debussy, Faure) Arabesque 6643 Sonata (1924) Gould Piano Trio Michael Schäfer, Ilona Then-Bergh, Wen-Sinn (+ Trio 2, La muse) Yang Champs Hill CHRCD140 [review] (+ Trio-Impromptu) Genuin GEN12236 [review] Grumiaux Trio (+ Trio 2) Talent 66 Camille Saint-Saëns 1835-1921, France Guarneri Trio (+ Martin, Ravel) Trio 1 in F, op. 18 (1863) Ottavo 28922 Altenberg Trio Wien Horszowski Trio (+ Trio 2) (+ Fauré, d’Indy) Challenge Classics SACC72111 Bridge 9441 [review][review] Aquinas Piano Trio Joachim Trio (+ Trio 2) (+ Trio 2) Guild GMCD7408 [review] Naxos 8.550935 Australian Trio Trio Latitude 41 (+ Trio 2, Muse, Swan, Septet, Cello & violin (+ Trio 2) sonatas) Eloquentia EL1547 ABC Classics 4766435 ABC Classics 4764327 Nash Ensemble MusicWeb International Updated: October 2020 Piano Trios: S Composers (+ Septet, Carnival of the -

Jascha Nemtsov: Publikationen

Jascha Nemtsov: Publikationen Monographien – Doppelt vertrieben: deutsch-jüdische Komponisten aus dem östlichen Europa in Palästina /Israel (= Jüdische Musik. Studien und Quellen zur jüdischen Musikkultur, Band 11), Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2013; – Louis Lewandowski. „Liebe macht das Lied unsterblich!“ (=Jüdische Miniaturen, Band 114), Verlag Hentrich & Hentrich, Berlin 2011 (zusammen mit Hermann Simon); Englischsprachige Version: Louis Lewandowski. „Love makes the melody immortal!“ (=Jewish Miniatures, Vol. 114a), Verlag Hentrich & Hentrich, Berlin 2011; – Deutsch-jüdische Identität und Überlebenskampf: jüdische Komponisten im Berlin der NS-Zeit (= Jüdische Musik. Studien und Quellen zur jüdischen Musikkultur, Band 10), Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2010; – Der Zionismus in der Musik: jüdische Musik und nationale Idee (= Jüdische Musik. Studien und Quellen zur jüdischen Musikkultur, Band 6), Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2009; – Oskar Guttmann (1885–1943) und Alfred Goodman (1919–1999) (= Jüdische Miniaturen, Band 89), Verlag Hentrich & Hentrich, Berlin 2009, – Arno Nadel (1878–1943). Sein Beitrag zur jüdischen Musikkultur (= Jüdische Miniaturen, Band 77), Verlag Hentrich & Hentrich, Berlin 2009, – Enzyklopädisches Findbuch des Potsdamer Archivs der Neuen Jüdischen Schule in der Musik (= Jüdische Musik. Studien und Quellen zur jüdischen Musikkultur, Band 8), Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2008; – Die Neue Jüdische Schule in der Musik (= Jüdische Musik. Studien und Quellen zur jüdischen Musikkultur, Band 2), Harrassowitz Verlag, -

Gained in Translation

Jascha Nemtsov, Dr habil., born in 1963 in Magadan (Russia). Studied piano at the Leningrad Conservatory (Concert The research project “Cultural Continuity Diploma with honors). In Germany since in the Diaspora – The Experience of Rus- 1992. Apart from the classical and ro- sian Jews in an Era of Social Change” is Gained in mantic piano repertoire, several concert based at the Department of European programs with works by Jewish and Rus- Studies and Modern Languages, Univer- sian composers of the 20th century. sity of Bath, and funded by the Lever- Translation Numerous radio recordings and by now 25 CDs as soloist and with partners hulme Trust UK. David Geringas (violoncello), Tabea Zim- www.bath.ac.uk/esml/rjccp/index.htm mermann (viola), Kolja Blacher, Dmitry Translations and Sitkovetsky and Ingolf Turban (violin), Chen Halevi (clarinet), the Vogler Quar- Their Influence tet and others. His CDs have been awar- ded many distinctions like “Audiophile Upon the Continuity Reference – The Best of 200”, “Klassik heute Empfehlung”, “CHOC - Le Mon- of Russian Jewish de de la Musique”, “Recording of the Culture in the West Month (MusicWeb)”, “Disc of the Month April 2006” (BBC Music Magazine), or the German Record Critics Prize (2007). Third international conference of the research project “Cultural Continuity in the Diaspora” For further information please contact: Jörg Schulte Department of Hebrew and Jewish [email protected] Studies & Institute of Jewish Studies University College London September 21-22, 2009 Monday, September 21 Tuesday, -

Ben-Haim · Bloch · Korngold

Ben-Haim · Bloch · Korngold Cello Concertos Raphael Wallfisch BBC National Orchestra of Wales Łukasz Borowicz VOICES IN THE WILDERNESS CELLO CONCERTOS BY EXILED JEWISH COMPOSERS Paul Ben-Haim (1897–1984) Cello Concerto (1962) 22'01 1 Allegro giusto 9'01 2 Sostenuto e languido 6'23 3 Allegro gioioso 6'37 Ernest Bloch (1880–1959) Symphony for Cello & Orchestra (1954) 17'52 4 Maestoso 3'25 5 Agitato 9'23 6 Allegro deciso 5'04 Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897–1957) All rights of the producer and of the owner of the work reserved. 7 Concerto in D in one movement 13'17 Unauthorized copying, hiring, renting, public performance and broadcasting 8 Tanzlied des Pierrot (from the opera Die tote Stadt) 4'17 of this record prohibited. cpo 555 273–2 (1880–1959) Ernest Bloch Recorded 31 October – 2 November 2018, BBC Hoddinott Hall 9 Vidui (1st movement of the Baal Shem-Suite) 3'00 Recording produced by Simon Fox-Gál Balance engineer: Simon Smith, BBC Wales 10 Nigun (2nd movement of the Baal Shem-Suite) 6'53 Edited by Jonathan Stokes and Simon Fox-Gál T.T.: 63'25 Executive Producers: Burkhard Schmilgun/Meurig Bowen Cover Painting: Felix Nussbaum, »Der Leierkastenmann«, 1931, Raphael WallfischVioloncello Berlin, Berlinische Galerie BBC National Orchestra of Wales © Photo: akg-images, 2019; Design: Lothar Bruweleit cpo, Lübecker Str. 9, D–49124 Georgsmarienhütte Łukasz Borowicz Conductor ℗ 2019 – Made in Germany Łukasz Borowicz © Katarzyna Zalewska Anmerkungen des Cellisten Paul Ben-Haim: sich alsbald Paul Ben-Haim (hebr. »Sohn des Hein- Konzert für Violoncello und Orchester rich«) nannte, ins Exil ging. -

Nr 34 (3/2017) ISSN: 2353-7094 Advisory Board Dr Vaclav Kapsa (Akademie Věd České Republiky) Dr Hab

nr 34 (3/2017) ISSN: 2353-7094 advisory board dr Vaclav Kapsa (Akademie věd České republiky) dr hab. Aleksandra Patalas (Uniwersytet Jagielloński w Krakowie) prof. Matthias Theodor Vogt (Institut für kulturelle Infrastruktur Sachsen) dr hab. Piotr Wilk (Uniwersytet Jagielloński w Krakowie) editorial staff Katarzyna Babulewicz Jolanta Bujas Marek Dolewka (Editor-in-Chief) Agnieszka Lakner Martyna Rodzeń Hubert Szczęśniak Justyna Szombara cover design and typesetting Agnieszka Bień proofreading Jolanta Bujas KMM UJ Editorial Staff abstracts’ translation Jolanta Bujas address Koło Naukowe Studentów Muzykologii UJ ul. Westerplatte 10 31–033 Kraków [email protected] This publication is supported by the Council of Scientific Students’ Organisations of the Jagiellonian University (Rada Kół Naukowych UJ). The participation of foreign reviewers in the evaluation of the publication was financed under the agreement No. 613/P-DUN/2017 from the funds of the Minister of Science and Higher Education for popularisation of science. Table of Contents Introduction 5 Federica Marsico 7 A Queer Approach to the Classical Myth of Phaedra in Music Marta Beszterda 29 At the Intersection of Musical Culture and Historical Legacy: Feminist Musicology in Poland Barbora Kubečková 51 Zdeněk Fibich (1850–1900) and his Songs to Goethe: Forgotten Settings? Clare Wilson 75 From the Inside Out: An Analytical Perspective of André Caplet’s Harmonic Evolution Through Selected Mélodies, 1915-1925 Nana Katsia 97 The Modification of the Genre of Mystery Play in the Wagner’s, Schoenberg’s and Messiaen’s Compositions Michał Jaczyński 115 The Presence of Jewish Music in the Musical Life of Interwar Prague Sylwia Jakubczyk-Ślęczka 135 Musical Life of the Jewish Community in Interwar Galicia. -

The Presence of Jewish Music in the Musical Life of Interwar Prague

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Jagiellonian Univeristy Repository Kwartalnik Młodych Muzykologów UJ nr 34 (3/2017), s. 115–133 DOI 10.4467/23537094KMMUJ.17.030.7859 www.ejournals.eu/kmmuj Michał Jaczyński JAGIELLONIAN UNIVERSITY IN KRAKÓW The Presence of Jewish Music in the Musical Life of Interwar Prague The subject matter of this article is the history of Jewish music’s pres- ence in the general culture of the interwar Prague. Both concepts—of the Jewish music and the general culture—require clarification. As for the latter issue, the author means the culture represented by the multinational audience of the leading concert halls and the readers of the high-volume Prague press, who for various reasons after 1918 became intensely interested in Jewish music, earlier cultivated mainly (though not only) within the diaspora. It cannot be assumed that the participants of the general music culture were exclusively members of non-Jewish audience; nevertheless, the meaning of the presence of Jewish music in this culture can be reduced to the mechanism of cultural exchange between Jewish and non-Jewish society, analogous to the one identified by Philip Bohlman, who described the career of Jewish music in the neighboring centers: Vienna and Budapest.1 Bohlman focused on these currents and genres of music that represent Jewish ethnos as the aim of his work was to enter the title issue into the modern discourse. The topic of his book is the connection between the expansion of Jewish music and the migration of rural Jews from Eastern Europe to modern Western metropolises. -

TFG- La Nova Escola Jueva

I Treball Fi de grau La Nova Escola Jueva Una renaixença cultural Estudiant: Isaac Bachs Viñuela Especialitat/ Àmbit/Modalitat: Interpretació CiC- Violí Director/a: Miguel Simarro Grande Curs: 2016-2017 Vistiplau del director/a del Treball EXTRACTE TRILÍNGÜE The present work aims to explain the elements that led to the birth of a jewish cultural renaissance in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as well as its development and subsequent influence on key composers of western music, such as Shostakovich and Prokofiev. Thereby, this work is widely documented from a printed bibliography of renowned jewish musicologists, such as Israel Adler and Abraham Idelssohn, as well as works made from the point of view of the performer, such as those made by pianists Jascha Nemtsov and Alexander Tentser, among others. Thanks to this work, I have found out that the New Jewish School was a stylistic embryo that later crystallized into the works of Shostakovich and Prokofiev, among others, and that, on the other hand, its members and repertoire have gone through an undeserved oblivion. El presente trabajo quiere explicar los factores que propiciaron el nacimiento de un renacer cultural judío a finales de siglo XIX y principios del XX, así como su desarrollo i la incidencia posterior en los compositores cruciales de la música occidental, como son Shostakovich i Prokofiev. Para ello, este trabajo está documentado ampliamente a partir de bibliografía impresa de musicólogos judíos especializados de gran nombre, como son Israel Adler y Abraham Idelssohn, así como de trabajos hechos desde la perspectiva del intérprete, como son los realizados por los pianistas Jascha Nemtsov y Alexander Tentser, entre otros. -

TOCC0343DIGIBKLT.Pdf

JOEL ENGEL Chamber Music and Folksongs I. KAPLAN (18??–19??) 1 Air (Jewish Melody) for violin, harp and harmonium (1912)* 2:59 JOEL ENGEL 2 Adagio Misterioso, Op. 22, for violin, cello, harp and harmonium* 4:57 Three Yiddish Songs for voice, oboe and piano, arr. Cantor Louis Danto 3 Nor nokh dir 2:25 4 Ritshkele 2:49 5 Akh! Nit gut! (Jüdische Volkslieder No.3, 1909) 2:30 The Dybbuk: Suite, Op. 35, for clarinet, strings and percussion 23:24 6 I For What Reason? – From Song of Songs (Mipneh Mah? – M’schir Haschirim) 5:09 7 II Beggars’ Dances (M’choloth Hakabzanim) 6:39 8 III Wedding March (Marsch Chatunah) 2:13 9 IV The Veiling of the Bride (Chipuy Hakalah) 2:34 10 V Hassidic Melody (Nigun Chassidim) 2:27 11 VI From Song of Songs – For What Reason? (reprise) 4:22 12 Hen hu hivtiach li for voice, violin and piano (1923)* 2:50 2 Violinstücke, Op. 20 7:01 13 No. 1 Chabad Nigun, for cello and piano arr. from violin version for cello by Uri Vardi 3:08 14 No. 2 Freylekhs, for violin and piano 3:53 2 Fifty Children’s Songs for voice and piano (1923) 15 No. 9 In der Suke 1:22 I. KAPLAN (18??–19??) 16 No. 8 Shavues 1:17 1 Air (Jewish Melody) for violin, harp and harmonium (1912)* 2:59 17 No. 1 Morgengebet* 1:09 JOEL ENGEL 11 Children’s Songs (Yaldei Sadeh), Op. 36 2 Adagio Misterioso, Op. 22, for violin, cello, harp and harmonium* 4:57 18 No. -

Twentieth-Century Composers

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: TWENTIETH -CENTURY COMPOSERS INSPIRED BY JEWISH CULTURE: SELECTIONS FROM THE SOLO AND COLLABORATIVE PIANO REPERTOIRE Susan M. Slingland, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2006 Dissertation directed by: Professor Rita Sloan School of Music Throughout the twentieth -century, many composers of both Jewish and non-Jewish descent found inspiration in the heritage of the Jewish people. The rise of nationalism and increased study of folk melodies and rhythms led to the exploration of the riches of Jewish music. The musicological premise of nationalism in music is that every nation has a unique history and therefore must have its own individualistic musical tradition. Due to the Diaspora, Jewish folksongs come in many diffe rent flavors but still convey the basic communal expression of their common struggle for existence, religion and culture. This is musical nationalism in the broadest possible sense. The dispersion of the Jewish people is reflected in the wide range of cu ltures into which they were assimilated: Slavic Eastern Europe, the Middle East (in particular, Israel), as well as the sephardic tradition of the Mediterranean regions and, of course, the melting pot of America. The composers featured in this performance dissertation project reflect that diversity. In many cases, composers drew upon the exoticism of Jewish music and re -interpreted it to pay homage to their own rich culture or to highlight the tragic history of the Jewish people in the first half of the tw entieth -century. The works considered for this topic are influenced by both sacred and secular melodies. These selections all include piano, whether it be art song, chamber music or solo repertoire. -

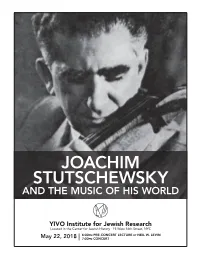

Joachim Stutschewsky and the Music of His World

JOACHIM STUTSCHEWSKY AND THE MUSIC OF HIS WORLD YIVO Institute for Jewish Research Located in the Center for Jewish History · 15 West 16th Street, NYC 6:00PM PRE-CONCERT LECTURE BY NEIL W. LEVIN May 22, 2018 | 7:00PM CONCERT PROGRAM אגדה (Legend (1952 יהויכין סטוצ’בסקי (JOACHIM STUTSCHEWSKY (b. 1891 UKRAINE – d. 1982 ISRAEL for cello and piano סוויטה חסידית (Hasidic Suite (1937 1. Hasidic Dance 2. Meditation 3. Hamavdil לזר סמינסקי (LAZARE SAMINSKY (b. 1882 UKRAINE – D. 1959 USA for cello and piano ֿפריילעכס (Freylekhs: Improvisation (1934 יהויכין סטוצ’בסקי (JOACHIM STUTSCHEWSKY (b. 1891 UKRAINE – d. 1982 ISRAEL for cello and piano מחול זעיר (Jolly Dance (1957 יהויכין סטוצ’בסקי (JOACHIM STUTSCHEWSKY (b. 1891 UKRAINE – d. 1982 ISRAEL for cello and piano ֿפריילעכס (Freylekhs, Op. 21 (1919 יואל אנגל (JOEL ENGEL (b. 1868 RUSSIAN EMPIRE – d. 1927 TEL AVIV for violin, cello, and piano פנטזיה חסידית (Hasidic Fantasy (1954 יהויכין סטוצ’בסקי (JOACHIM STUTSCHEWSKY (b. 1891 UKRAINE – d. 1982 ISRAEL for clarinet, cello, and piano BRIEF INTERMISSION מוסיקה לצ’לו (Music for Violoncello (1977 1. Moderato 2. Rather fast, lively 3. Slow פאול בן-חיים (PAUL BEN-HAIM (b. 1897 GERMANY – d. 1984 ISRAEL for solo cello ניגון והורה (Nigun & Hora* (2018 ניגון: ״יזכור״ The Yizkor Nigun .1 הורה להבה The Flaming Hora .2 עופר בן-אמוץ (OFER BEN-AMOTS (b. 1955 ISRAEL for cello and piano שיר יהודי (Shir Yehudi (1937 יהויכין סטוצ’בסקי (JOACHIM STUTSCHEWSKY (b. 1891 UKRAINE – d. 1982 ISRAEL for cello and piano מוסיקה כליזמרית לחתונה (Klezmer’s Wedding Music (1955 יהויכין סטוצ’בסקי (JOACHIM STUTSCHEWSKY (b.