Land Reform and New Meaning of Rural Development in Zimbabwe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PLAAS RR46 Smeadzim 1.Pdf

Chrispen Sukume, Blasio Mavedzenge, Felix Murimbarima and Ian Scoones Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences Research Report 46 Space, Markets and Employment in Agricultural Development: Zimbabwe Country Report Chrispen Sukume, Blasio Mavedzenge, Felix Murimbarima and Ian Scoones Published by the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, University of the Western Cape, Private Bag X17, Bellville 7535, Cape Town, South Africa Tel: +27 21 959 3733 Fax: +27 21 959 3732 Email: [email protected] Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies Research Report no. 46 June 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission from the publisher or the authors. Copy Editor: Vaun Cornell Series Editor: Rebecca Pointer Photographs: Pamela Ngwenya Typeset in Frutiger Thanks to the UK’s Department for International Development (DfID) and the Economic and Social Research Council’s (ESRC) Growth Research Programme Contents List of tables ................................................................................................................ ii List of figures .............................................................................................................. iii Acronyms and abbreviations ...................................................................................... v 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................ -

MASHONALAND EAST PROVINCE - Basemap

MASHONALAND EAST PROVINCE - Basemap Mashonaland Central Karanda Chimandau Guruve MukosaMukosa Guruve Kamusasa Karanda Marymount Matsvitsi Marymount Mary Mount Locations ShinjeShinje Horseshoe Nyamahobobo Ruyamuro RUSHINGA CentenaryDavid Nelson Nyamatikiti Nyamatikiti Province Capital Nyakapupu M a z o w e CENTENARY Mazowe St. Pius MOUNT DARWIN 2 Chipuriro Mount DarwinZRP NyanzouNyanzou Mt Darwin Chidikamwedzi Town 17 GoromonziNyahuku Tsakare GURUVE Jingamvura MAKONDE Kafura Nyamhondoro Place of Local Importance Bepura 40 Kafura Mugarakamwe Mudindo Nyamanyora Chingamuka Bure Katanya Nyamanyora Bare Chihuri Dindi ARDA Sisi Manga Dindi Goora Mission M u s e n g e z i Nyakasoro KondoKondo Zvomanyanga Goora Wa l t o n Chinehasha Madziwa Chitsungo Mine Silverside Donje Madombwe Mutepatepa Nyamaruro C o w l e y Chistungo Chisvo DenderaDendera Nyamapanda Birkdale Chimukoko Nyamapanda Chindunduma 13 Mukodzongi UMFURUDZI SAFARI AREA Madziwa Chiunye KotwaKotwa 16 Chiunye Shinga Health Facility Nyakudya UZUMBA MARAMBA PFUNGWE Shinga Kotwa Nyakudya Bradley Institute Borera Kapotesa Shopo ChakondaTakawira MvurwiMvurwi Makope Raffingora Jester H y d e Maramba Ayrshire Madziwa Raffingora Mvurwi Farm Health Scheme Nyamaropa MUDZI Kasimbwi Masarakufa Boundaries Rusununguko Madziva Mine Madziwa Vanad R u y a Madziwa Masarakufa Shutu Nyamukoho P e m b i Nzvimbo M u f u r u d z i Madziva Teacher's College Vanad Nzvimbo Chidembo SHAMVA Masenda National Boundary Feock MutawatawaMutawatawa Mudzi Rosa Muswewenhede Chakonda Suswe Mutorashanga Madimutsa Chiwarira -

Census Results in Brief

116 Appendix 1a: Census Questionnaire 117 118 119 120 Appendix 1b: Census Questionnaire Code List Question 6-8 and 10 Census District Country code MANICALAND 1 Sanyati 407 Shurugwi 726 Rural Districts Urban Areas MASVINGO 8 Buhera 101 Chinhoyi 421 Rural Districts Chimanimani 102 Kadoma 422 Bikita 801 Chipinge 103 Chegutu 423 Chiredzi 802 Makoni 104 Kariba 424 Chivi 803 Mutare Rural 105 Norton 425 Gutu 804 Mutasa 106 Karoi 426 Masvingo Rural 805 Nyanga 107 MATABELELAND NORTH 5 Mwenezi 806 Urban Areas Rural Districts Zaka 807 Mutare 121 Binga 501 Urban Areas Rusape 122 Bubi 502 Masvingo Urban 821 Chipinge 123 Hwange 503 Chiredzi Town 822 MASHONALAND CENTRAL 2 Lupane 504 Rural Districts Nkayi 505 HARARE 9 Bindura 201 Tsholotsho 506 Harare Rural 901 Centenary 202 Umguza 507 Harare Urban 921 Guruve 203 Urban Areas Chitungwiza 922 Mazowe 204 Hwange 521 Epworth 923 Mount Darwin 205 Victoria Falls 522 BULAWAYO 0 Rushinga 206 MATABELELAND SOUTH 6 Bulawayo Urban 21 Shamva 207 Rural Districts AFRICAN COUNTRIES Mbire 208 Beitbridge Rural 601 Zimbabwe 0 Urban Areas Bulilima 602 Botswana 941 Bindura 221 Mangwe 603 Malawi 942 Mvurwi 222 Gwanda Rural 604 Mozambique 943 MASHONALAND EAST 3 Insiza 605 South Africa 944 Rural Districts Matobo 606 Zambia 945 Chikomba 301 Umzingwane 607 Other African Countries 949 Goromonzi 302 Urban Areas OUTSIDE AFRICA Hwedza 303 Gwanda 621 United Kingdom 951 Marondera 304 Beitbridge Urban 622 Other European Countries 952 Mudzi 305 Plumtree 623 American Countries 953 Murehwa 306 MIDLANDS 7 Asian Countries 954 Mutoko 307 Rural Districts Other Countries 959 701 Seke 308 Chirumhanzu Uzumba-Maramba-Pfungwe 309 Gokwe North 702 Urban Areas Gokwe South 703 Marondera 321 Gweru Rural 704 Chivhu Town Board 322 Kwekwe Rural 705 Ruwa Local Board 323 Mberengwa 706 MASHONALAND WEST 4 Shurugwi 707 Rural Districts Zvishavane 708 Chegutu 401 Urban Areas Hurungwe 402 Gweru 721 Mhondoro-Ngezi 403 Kwekwe 722 Kariba 404 Redcliff 723 Makonde 405 Zvishavane 724 Gokwe Centre 725 . -

National Rapid Response Team Contacts

National Rapid Response Team Contacts City/Town Contact Person Mobile Number Toll free Number Institution/Role Ace Ambulance +263 782999901-4 (0) 8080412 Harare ZRP (0242) 777777 ZRP Harare - Wilkins (0242) 741872 Wilkins Hosp Harare - Wilkins (0242) 740404 Wilkins Hosp Harare Dr Chonzi +263 712860777 Harare Dr Bara +263 734322293 Harare Dr Mudariki +263 772974314 Bulawayo Ms Sibanda +263 772677476 Bulawayo Dr Nyathi +263 776248128 Bulawayo Dr Ncube +263 772424812 Bulawayo Dr E Sibanda +263 772880581 Director Health Services Bulilima Dr Hapanyengwi +263 772907621 Beitbridge Dr Samhere +263 772386895 Bindura Mr Karisa +263 773271670 DMO Bikita Dr Mungwari +263 715411650 Centenary/Muzarabani Mr Kangundu +263 777366045 DNO Chegutu Dr Masvosva +263 772720190 Chiredzi Dr Dhlandhlara +263 775094360 Chirumanzu Dr S Maunga +263 772286685 (0) 8080435 Chirumanzu Mr Mukomberanwa +263 773 394 154 (0) 8080435 Chirumanzu Sr Mutumwa +263 772 911 454 (0) 8080435 Concession Dr Sosera +263 774736753 Gokwe North DR Chikara +263 775 428800 Gokwe North E Muchenje +263772 575437 City/Town Contact Person Mobile Number Toll free Number Institution/Role Gokwe South DR Mashoko +263 774 074739 Gokwe South D Mukotsi +263 774 002 934 Goromonzi Dr Karim +263 772347378 Guruve Zvomuya +263 772641444 DNO Gwanda Dr Gwarimbo +263 775735679 Gweru Dr Mhene +263 773258210 (0) 8080435 Gweru Provincial Hosp Toll free +263 787822276 (0) 8080435 Gweru Provincial Hospital Gweru& City G Shariwa +263 773 639 797 (0) 8080435 Gweru& City Mr Sekanhamo +263 715017014 (0) 8080435 Gweru& -

Lions Clubs International Club Membership Register the Clubs and Membership Figures Reflect Changes As of March 2005

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF MARCH 2005 CLUB MMR MMR FCL YR MEMBERSHI P CHANGES TOTAL TYPE IDENT NBR CLUB NAME DIST RPT DATE RCV DATE OB NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERS 7300 027882 BANKET-TRELAWNEY 412 8 0 0 0 0 0 8 7300 027883 BEIT BRIDGE 412 1 10-2004 10-14-2004 -4 -4 4 0 0 0 -4 -4 0 7300 027886 BULAWAYO 412 1 07-2004 08-18-2004 7300 027886 BULAWAYO 412 1 08-2004 08-18-2004 7300 027886 BULAWAYO 412 1 08-2004 08-18-2004 7300 027886 BULAWAYO 412 1 09-2004 09-17-2004 1 1 7300 027886 BULAWAYO 412 1 09-2004 10-01-2004 7300 027886 BULAWAYO 412 1 10-2004 10-01-2004 7300 027886 BULAWAYO 412 1 11-2004 11-26-2004 7300 027886 BULAWAYO 412 1 12-2004 12-06-2004 7300 027886 BULAWAYO 412 1 01-2005 01-14-2005 7300 027886 BULAWAYO 412 1 02-2005 02-05-2005 7300 027886 BULAWAYO 412 1 03-2005 03-01-2005 21 0 1 0 0 1 22 7300 027887 BULAWAYO MATOPOS 412 1 06-2004 03-01-2005 2 -5 -3 7300 027887 BULAWAYO MATOPOS 412 1 07-2004 03-01-2005 7300 027887 BULAWAYO MATOPOS 412 1 08-2004 03-01-2005 7300 027887 BULAWAYO MATOPOS 412 1 09-2004 03-01-2005 7300 027887 BULAWAYO MATOPOS 412 1 10-2004 03-01-2005 7300 027887 BULAWAYO MATOPOS 412 1 11-2004 03-01-2005 7300 027887 BULAWAYO MATOPOS 412 1 12-2004 03-01-2005 -2 -2 7300 027887 BULAWAYO MATOPOS 412 1 01-2005 03-01-2005 7300 027887 BULAWAYO MATOPOS 412 1 02-2005 03-01-2005 7300 027887 BULAWAYO MATOPOS 412 1 03-2005 03-22-2005 20 2 0 0 -7 -5 15 7300 027889 CHIREDZI 412 1 05-2004 08-18-2004 7300 027889 CHIREDZI 412 1 06-2004 08-18-2004 7300 -

MASHONALAND EAST PROVINCE - Overview Map 26 October 2009 Legend Province Capital

MASHONALAND EAST PROVINCE - Overview Map 26 October 2009 Legend Province Capital Hunyani Casembi Key Location Chikafa Chidodo Muzeza Musengezi Mine Mushumbi Musengezi Pools Chadereka Mission Mbire Mukumbura Place of Local Importance Hoya Kaitano Kamutsenzere Kamuchikukundu Bwazi Muzarabani Mavhuradonha Village Bakasa St. St. Gunganyama Pachanza Centenary Alberts Alberts Nembire Road Network Kazunga Chawarura Dotito Primary Chironga Rushinga Mount Rushinga Mukosa Guruve Karanda Rusambo Marymount Chimanda Secondary Marymount Shinje Darwin Rusambo Centenary Nyamatikiti Guruve Feeder azowe MashonalandMount M River Goromonzi Darwin Mudindo Dindi Kafura Bure Nyamanyora Railway Line Central Goora Kondo Madombwe Chistungo Mutepatepa Dendera Nyamapanda International Boundary Madziwa Borera Chiunye Kotwa Nyakudya Shinga Bradley Jester Mvurwi Madziwa Vanad Kasimbwi Institute Masarakufa Nzvimbo Madziwa Province Boundary Feock Mutawatawa Mudzi Muswewenhede Chakonda Suswe Mudzi Mutorashanga Charewa Chikwizo Howard District Boundary Nyota Shamva Nyamatawa Gozi Institute Bindura Chindengu Kawere Muriel Katiyo Rwenya Freda & Mont Dor Caesar Nyamuzuwe River Mazowe Rebecca Uzumba Nyamuzuwe Katsande Makaha River Shamva Mudzonga Makosa Trojan Shamva Nyamakope Fambe Glendale BINDURA MarambaKarimbika Sutton Amandas Uzumba All Nakiwa Kapondoro Concession Manhenga Kanyongo Souls Great Muonwe Mutoko PfungweMuswe Dyke Mushimbo Chimsasa Lake/Waterbody Madamombe Jumbo Bosha Nyadiri Avila Makumbe Mutoko Jumbo Mazowe Makumbe Parirewa Nyawa Rutope Conservation Area -

Zimbabwe Livelihood Zone Profiles. December 2010

Zimbabwe Livelihoods Zone VAC ZIMBABWE Profiles Vulnerability Assessment Committee 15 February 2010 The Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee (ZimVac) is Chaired by the Food and Nutrition Council (FNC) which is housed at the Scientific Industrial Research and Developing Council (SIRDC), Harare, Zimbabwe. Acknowledgements The Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee (ZimVac) would like to express its appreciation for the financial, technical and logistical support that the following agencies provided towards the data collection, analysis and writing-up of the Revised Livelihoods profiles for Zimbabwe; Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation Development and Mechanizations’ Department of Agricultural Extension Services (AGRITEX) Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare’s Department of Social Welfare Ministry of Finance’s Central Statistical Office (CSO) Ministry of Education’s Curriculum Development Ministry of Transport’s Department of Meteorological Services United Nations’ World Food Programme (WFP) United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) United Nations’ Office of Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) World Vision (WV) OXFAM ACTIONAID Save the Children United Kingdom (SC-UK) Southern Africa Development Community Regional Vulnerability Assessment Committee (RVAC) United States of America International Development Agency (USAID) Department for International Development (DFID) The European Commission (EC) FEG (The Food Economy Group) The Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWSNET) The revision -

FSC Map Atlas

FSC Map atlas As of April 2020 Summary: 1. Partners Presence SO1 - Wards in which individuals are receiving food assistance 2. Partners Presence SO2 - Wards in which individuals are receiving agriculture and livelihood assistance 3. GAP Analysis - People targeted and people reached by province 4. FSL interventions: Implementation of COVID-19 mitigation and protection measures Zimbabwe Partners Presence SO1 - Wards in which individuals are receiving food assistance as of April 2020 About:This map shows wards where interventions have been conducted in the month of April 2020. It clearly identifies wards where no intervention has been Harare reported as of May 2020 and where gaps could remain. DanChurch Aid (WFP):Mobile Money Mashonaland Central Planned Mashonaland West AFRICARE(WFP):In-kind ZCC:Mobile Money AQZ (WFP):In-kind CTDO(WFP):In-kind Mashonaland East CARE:Mobile Money LGDA(WFP):In-kind ADRA (WFP):In-kind CARE (WFP):Mobile Money World Vision(WFP):In-kind CARITAS (WFP):In-kind CTDO (WFP):In-kind ZRCS(WFP):In-kind CTDO (WFP):In-kind LEAD (WFP):In-kind GOAL (WFP):Mobile Money LGDA (WFP):In-kind TDH (WFP):In-kind World Vision(WFP):In-kind World Vision (WFP):In-kind ZRCS (WFP):In-kind World Vision (WFP):In-kind Planned Planned ZCC:Mobile Money ZCC-CC:In-kind, Hurungwe Mbire Mobile Money Midlands Centenary/ Muzarabani ADRA:In-kind Kariba Mount Urban Rushinga ADRA(WFP):In-kind Guruve Darwin Aficare(WFP):In-kind Karoi Mashonaland Caritas(CAFOD):CBS++ Kariba Central HOCIC(WFP):In-kind Mvurwi UMP Mudzi Shamva LID Agency(WFP):In-kind Mazowe -

Your Phone Number Has Been Updated!

Your phone number has been updated! We have changed your area code, and have updated your phone number. Now you can enjoy the full benefits of a converged network. This directory guides you on the changes to your number. TELONE NUMBER CHANGE UPDATE City/Town Old Area New Area Prefix New number example City/Town Old Area New Area Prefix New number example Code Code Code Code Arcturus 0274 024 214 (024) 214*your number* Lalapanzi 05483 054 2548 (054) 2548*your number* Banket 066 067 214 (067) 214*your number* Lupane 0398 081 2856 (081) 2856*your number* Baobab 0281 081 28 (081)28*your number* Macheke 0379 065 2080 (065) 2080*your number* Battlefields 055 055 25 (055)25*your number* Makuti 063 061 2141 (061) 2141*your number* Beatrice 065 024 2150 (024) 2150*your number* Marondera 0279 065 23 (065) 23*your number* Bindura 0271 066 210 (066) 210*your number* Mashava 035 039 245 (039) 245*your number* Birchenough Bridge 0248 027 203 (027) 203*your number* Masvingo 039 039 2 (039) 2*your number* (029)2*your number* Mataga 0517 039 2366 (039) 2366*your number* Bulawayo 09 029 2 (for numbers with 6 digits) Matopos 0383 029 2809 (039) 2809*your number* (029)22*your number) Bulawayo 09 029 22 Mazowe 0275 066 219 (066) 219*your number* (for numbers with 5 digits) Mberengwa 0518 039 2360 (039)2360*your number* Centenary 057 066 210 (066) 210*your number* Chatsworth 0308 039 2308 (039)2308*your number* Mhangura 060 067 214 (067) 214*your number* Mount Darwin 0276 066 212 (066) 212*your number* Chakari 0688 068 2189 (068) 2189*your number* Murambinda -

Land Reform, Commercial Agriculture and Local Economic Growth in Zimbabwe

Land reform, commercial agriculture and local economic growth in Zimbabwe Blasio Mavedzenge, Felix Murimbarimba, Ian Scoones and Chrispen Sukume Introduction Land reform in Zimbabwe has radically transformed the rural economy. After 2000, around 145,000 families were allocated smallholder plots and a further 20,000 took on medium scale farms. This replaced an agrarian structure that was divided between 4,500 large- scale commercial farms and many small communal area farms. The new farmers have had many challenges, but they have also created employment and are generating new economic linkages, both in the local economy and further afield. In the last few years we have looked at this unfolding dynamic by tracing the networks of economic activity from a series of farms in two sites – Mvurwi in Mazowe district, a high potential area near the capital, and Wondedzo near Masvingo, in the drier southeast. By looking at four commodities – tobacco, horticulture, beef and maize - we asked: what are the economic linkages created by new farming enterprises, how are these influencing the local economy, what livelihoods and forms of employment are being created, and what challenges are being faced? 1 A number of important value chains. Since land Permanent employees are findings emerge: reform, a dualistic agrarian often kin, or from the structure has largely been farmer-employer’s original Agricultural production replaced by a mix of small ‘home’ area. In areas made possible by land and medium sized farms where ‘compound’ labour reform has created a wide (A1 and A2 in the new was common, such as range of economic activity resettlements). -

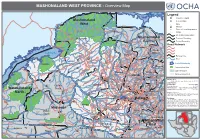

MASHONALAND WEST PROVINCE - Overview Map

MASHONALAND WEST PROVINCE - Overview Map Kanyemba Mana Lake C. Bassa Pools Legend Province Capital Mashonaland Key Location r ive R Mine zi West Hunyani e Paul V Casembi b Chikafa Chidodo Mission Chirundu m Angwa Muzeza a Bridge Z Musengezi Place of Local Importance Rukomechi Masoka Mushumbi Musengezi Mbire Pools Chadereka Village Marongora St. International Boundary Cecelia Makuti Mashonaland Province Boundary Hurungwe Hoya Kaitano Kamuchikukundu Bwazi Chitindiwa Muzarabani District Boundary Shamrocke Bakasa Central St. St. Vuti Alberts Alberts Nembire KARIBA Kachuta Kazunga Chawarura Road Network Charara Lynx Centenary Dotito Kapiri Mwami Guruve Mount Lake Kariba Dora Shinje Masanga Centenary Darwin Doma Mount Maumbe Guruve Gachegache Darwin Railway Line Chalala Tashinga KAROI Kareshi Magunje Bumi Mudindo Bure River Hills Charles Mhangura Nyamhunga Clack Madadzi Goora Mola Mhangura Madombwe Chanetsa Norah Silverside Mutepatepa Bradley Zvipane Chivakanyama Madziwa Lake/Waterbody Kariba Nyakudya Institute Raffingora Jester Mvurwi Vanad Mujere Kapfunde Mudzumu Nzvimbo Shamva Conservation Area Kapfunde Feock Kasimbwi Madziwa Tengwe Siyakobvu Chidamoyo Muswewenhede Chakonda Msapakaruma Chimusimbe Mutorashanga Howard Other Province Negande Chidamoyo Nyota Zave Institute Zvimba Muriel Bindura Siantula Lions Freda & Mashonaland West Den Caesar Rebecca Rukara Mazowe Shamva Marere Shackleton Trojan Shamva Chete CHINHOYI Sutton Amandas Glendale Alaska Alaska BINDURA Banket Muonwe Map Doc Name: Springbok Great Concession Manhenga Tchoda Golden -

Zimbabwe Lean Season Assistance – Januar Y - Apr Il 2021

Zimbabwe Lean Season assistance – Januar y - Apr il 2021 This map aims to represent the level of achievement related to food assistance response for the period Jan-Apr 2021. The selection of the period derives from two major factors: 1) data are available for all actors, and 2) the period coincides with the peak and end of the lean season response plan of major aid agencies. The gradient of the colours shows the ratio of the achievement at district level, calculated considering all beneficiaries reached against the estimation of people in need elaborated in October 2020, and according to the following criteria: People reached:for each agency, it was considered the maximum number of beneficiaries reported in any month. This is because food assistance is supposed to operate by monthly cycle for the same households being served every month of the programme. Both government and non-governmental agencies, including the UN, are included in this map. People in need:it was used the estimation of people in need from the ZimVAC rural assessment, and the WFP CARI report for the urban areas. This choice was made in order to consider all people in need who were supposed to be reached by the implementation of all programmes. Mbire Hurungwe Centenary/ Muzarabani Kariba Urban Mount Rushinga Guruve Darwin Karoi Kariba Bindura Mvurwi Mudzi Mashonaland Shamva Mashonaland West Chinhoyi Bindura Urban UMP East Makonde Mazowe Mutoko Gokwe North Zvimba Goromonzi Harare Binga Harare Murehwa Victoria Chegutu NortonHarare Rural Falls Sanyati Chitungwiza Gokwe Chegutu