THE RIGHTS of FIREFIGHTERS (Fourth Edition)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FIRE DEPARTMENT COUNTY Adair County Tri Community Volunteer Fire Dept

FIRE DEPARTMENT COUNTY Adair County Tri Community Volunteer Fire Dept. Adair Bell Rural Fire Department Inc Adair Chance Community Fire Department Inc. Adair Christie Proctor Fire Association Adair Greasy Volunteer Fire Department Inc. Adair Hwy 100 West Fire Protection Adair Hwy 51 West Rural Fire District, Inc. Adair Mid County Rural Fire Dept. Inc. Adair Town of Stilwell for Stilwell Fire Department Adair Town of Watts for Watts Fire Department Adair Town of Westville for Westville Fire Department Adair City of Cherokee for Cherokee Fire Department Alfalfa Nescatunga Rural Fire Association Alfalfa Town of Aline for Aline Fire Department Alfalfa Town of Burlington for Burlington Fire Department Alfalfa Town of Byron for A&B Fire Department Alfalfa Town of Carmen for Carmen Fire Department Alfalfa Town of Goltry for Goltry Fire Department Alfalfa Town of Helena for Helena Fire Department Alfalfa Town of Jet for Jet Fire Department Alfalfa Bentley Volunteer Fire District Atoka City of Atoka for Atoka Fire Department Atoka Crystal Volunteer Fire Department Association Atoka Daisy Volunteer Fire Department, Inc. Atoka Farris Fire District Atoka Harmony Fire Department Atoka Hopewell Community Firefighters Association Atoka Lane Volunteer Fire Department Association Atoka Town of Caney for Caney Fire Department Atoka Town of Stringtown for Stringtown Fire Department Atoka Town of Tushka for Tushka Fire Department Atoka Wards Chapel Fire Department, Inc. Atoka Wardville Rural Volunteer Fire Dept. Atoka Wilson Community Rural Fire Association -

Tennessee County Fire Handbook Prepared by Kevin J

Tennessee County Fire Handbook prepared by Kevin J. Lauer, Fire Management Consultant EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF STATEWIDE ANALYSIS CURRENT ASSESSMENT OF FIRE PROTECTION CAPABILITIES COUNTY EXECUTIVE/ MAYOR’S SURVEY FIRE DEPARTMENT SURVEY ISO RATINGS AND COUNTY GOVERNMENT COUNTY WATER SUPPLY PLANNING FIRE PREVENTION FIRE DEPARTMENT FUNDING FORMATION OF A COUNTYWIDE FIRE DEPARTMENT RECRUITMENT AND RETENTION TRAINING TENNESSEE COUNTY FIRE HANDBOOK Kevin J. Lauer Fire Management Consultant Dedication The Tennessee County Fire Handbook is dedicated in both new and existing buildings. Over time the to Dwight and Gloria Kessel. Dwight Kessel gave fire bureau expanded to provide public education 31 years of dedicated service to the people of and fire/arson investigation as well as code Knox County as a Knoxville City Council member, enforcement. This approach was unprecedented at Knox County Clerk and County Executive. During the time on a county level and remains a model his tenure as County Executive, Kessel oversaw that most counties in the state should study to tremendous growth in the county’s population improve life safety and property loss reduction. and services provided. The county was handed several duplicate governmental services from Even after Kessel’s tenure in office, he has the city such as schools, jails, libraries and continued to improve county government across indigent care (which became a model that other the state. The Kessel’s generous endowment communities across the nation studied and used to the University of Tennessee was earmarked to improve their delivery of indigent care). All for special projects that the County Technical were successfully absorbed into the realm of Assistance Service (CTAS) would not normally county services. -

Safeguard Properties Western Wildfire Reference Guide

Western U.S. Wildfire Reference Guide | 11/19/2020 | Disaster Alert Center Recent events reportedly responsible for structural damage (approximate): California August Complex Fire (1,032,648 acres; 100% containment) August 16 – Present Mendocino, Humboldt, Trinity, Tehama, Lake, Glenn and Colusa Counties 54 structures destroyed; 6 structures damaged Approximate locations at least partially contained in event perimeter: Alder Springs (Glenn County, 95939) Bredehoft Place (Mendocino County, 95428) Chrome (Glenn County, 95963) Covelo (Mendocino County, 95428) Crabtree Place (Trinity County, 95595) Forest Glen (Trinity County, 95552) Hardy Place (Mendocino County, 95428) Houghton Place (Tehama County, 96074) Kettenpom (Trinity County, 95595) Mad River (Trinity County, 95526, 95552) Red Bluff (Tehama County, 96080) Ruth (Trinity County, 95526) Shannon Place (Trinity County, 95595) Zenia (Trinity County, 95595) Media: https://www.appeal-democrat.com/colusa_sun_herald/august-complex-100-percent-contained/article_64231928-2903- 11eb-8f83-97a9edd02eec.html P a g e 1 | 16 Western U.S. Wildfire Reference Guide | 11/19/2020 | Disaster Alert Center Blue Ridge Fire (14,334 acres; 100% containment) October 26 – November 7 Orange/San Bernardino/Riverside counties 1 structure destroyed; 10 structures damaged Approximate locations at least partially contained in event perimeter: Chino Hills (San Bernardino County, 91709) Corona (Riverside County, 92880*) *Impacted ZIP code only Yorba Linda (Orange County, 92885, 92886, 92887) Media: -

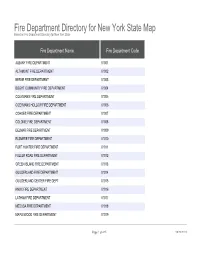

Fire Department Directory for New York State Map Based on Fire Department Directory for New York State

Fire Department Directory for New York State Map Based on Fire Department Directory for New York State Fire Department Name Fire Department Code ALBANY FIRE DEPARTMENT 01001 ALTAMONT FIRE DEPARTMENT 01002 BERNE FIRE DEPARTMENT 01003 BOGHT COMMUNITY FIRE DEPARTMENT 01004 COEYMANS FIRE DEPARTMENT 01005 COEYMANS HOLLOW FIRE DEPARTMENT 01006 COHOES FIRE DEPARTMENT 01007 COLONIE FIRE DEPARTMENT 01008 DELMAR FIRE DEPARTMENT 01009 ELSMERE FIRE DEPARTMENT 01010 FORT HUNTER FIRE DEPARTMENT 01011 FULLER ROAD FIRE DEPARTMENT 01012 GREEN ISLAND FIRE DEPARTMENT 01013 GUILDERLAND FIRE DEPARTMENT 01014 GUILDERLAND CENTER FIRE DEPT 01015 KNOX FIRE DEPARTMENT 01016 LATHAM FIRE DEPARTMENT 01017 MEDUSA FIRE DEPARTMENT 01018 MAPLEWOOD FIRE DEPARTMENT 01019 Page 1 of 425 09/28/2021 Fire Department Directory for New York State Map Based on Fire Department Directory for New York State Address City State 26 BROAD STREET ALBANY NY 115 MAIN STREET PO BOX 642 ALTAMONT NY CANADAY ROAD BERNE NY 1095 LOUDON ROAD COHOES NY 67 CHURCH STREET COEYMANS NY 1290 ROUTE 143 COEYMANS HOLLOW NY 97 MOHAWK STREET COHOES NY 1631 CENTRAL AVENUE ALBANY NY 145 ADAMS STREET DELMAR NY 15 WEST POPLAR DRIVE DELMAR NY 3525 CARMAN ROAD SCHENECTADY NY 1342 CENTRAL AVENUE ALBANY NY 7 CLINTON STREET GREEN ISLAND NY 2303 WESTERN AVE GUILDERLAND NY 30 SCHOOL ROAD GUILDERLAND CENTER NY 2198 BERNE ALTAMONT ROAD KNOX NY 226 OLD LOUDON ROAD LATHAM NY 458 CR 351 MEDUSA NY 61 COHOES ROAD WATERVLIET NY Page 2 of 425 09/28/2021 Fire Department Directory for New York State Map Based on Fire Department -

Tab 7 Fire Service in Tennessee

Report of the Tennessee Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations Fire Service in Tennessee 2 Contents An Examination of Fire Service Funding in Tennessee .............................................................. 5 Tennessee Ranks High for Fire Losses .................................................................................. 5 Issues Raised by House Joint Resolution 204 ........................................................................ 6 How Fire Service is Provided in Tennessee ................................................................................ 7 Mutual Aid ........................................................................................................................... 8 Fire Service Coverage .......................................................................................................... 9 Fire Service Funding ............................................................................................................ 10 Counties can establish fire tax districts with differential property tax rates ...................... 12 All fire departments can charge fees for service ............................................................... 12 Additional ways to reduce fire losses ................................................................................... 13 Smoke Alarms ................................................................................................................. 14 Sprinklers ....................................................................................................................... -

California Directory of Building, Fire, and Water Agencies

California Directory Of Building, Fire, And Water Agencies American Society of Plumbing Engineers Los Angeles Chapter www.aspela.com Kook Dean [email protected] California Directory Of Building, Fire, And Water Agencies American Society of Plumbing Engineers Los Angeles Chapter www.aspela.com Kook Dean [email protected] 28415 Pinewood Court, Saugus, CA 91390 Published by American Society of Plumbing Engineers, Los Angeles Chapter Internet Address http://www.aspela.com E-mail [email protected] Over Forty years of Dedication to the Health and safety of the Southern California Community A non-profit corporation Local chapters do not speak for the society. Los Angeles Chapter American Society of Plumbing Engineers Officers - Board of Directors Historian President Treasurer RICHARD REGALADO, JR., CPD VIVIAN ENRIQUEZ KOOK DEAN, CPD Richard Regalado, Jr., Mechanical Consultants Arup City of Los Angeles PHONE (626) 964-9306 PHONE (310) 578-4182 PHONE (323) 342-6224 FAX (626) 964-9402 FAX (310) 577-7011 FAX (323) 342-6210 [email protected] [email protected] Administrative Secratary ASPE Research Foundation Vice President - Technical Walter De La Cruz RON ROMO, CPD HAL ALVORD,CPD South Coast Engineering Group PHONE (310) 625-0800 South Coast Engineering Group PHONE (818) 224-2700 [email protected] PHONE (818) 224-2700 FAX (818) 224-2711 FAX (818) 224-2711 [email protected] Chapter Affiliate Liaison: [email protected] RON BRADFORD Signature Sales Newsletter Editor Vice President - Legislative PHONE (951) 549-1000 JEFF ATLAS RICHARD DICKERSON FAX (957) 549-0015 Symmons Industries, Inc. Donald Dickerson Associates [email protected] PHONE (714) 373-5523 PHONE (818) 385-3600 FAX (661) 297-3015 Chairman - Board of Governors FAX (818) 990-1669 [email protected] Cory S. -

RETAC Contacts 13 Search and Technical Rescue

Foothills RETAC Medical Resource Guide Table of Contents Sect. Title 1 Caches (MCI and Surge) 2 Critical Care Transport Services 3 Dispatch Centers 4 Emergency Managers 5 Facility Bio-Phone and PCR Fax Numbers 6 Facilities/Facility Resources 7 Fire Agencies 8 Flight Services 9 Ground Transporting Agencies 10 Health Departments 11 Medical Directors 12 RETAC Contacts 13 Search and Technical Rescue * All Data Contained in this guide is self-reported or found on public websites Names and specific information may change between updates Section 1 Caches Includes MCI and Surge Caches Prehospital Resources/Medical Supply Caches Resource County Location Directions for Pick-Up Activation Trailer Specifics Contact Info MCI Caches Boulder County AMR Boulder Office Directions for Pick-Up Activation Trailer Info Contact Info This cache is located in the Boulder Office of AMR Activation: 303 441-4444 This cache will be kept in an old American Medical Ambulance, 3800 Pearl St., Boulder, Colorado. This is the dispatch center. ambulance and NOT in a trailer. Response From Highway 36 take Foothills Parkway north to the Please have the Dispatch center Please notify the Boulder 3800 Pearl St Pearl St. exit and turn left(west) onto Pearl Parkway. notify the Boulder Operations Communications Center at the Boulder, Co. 80301 Go two blocks to Frontier and turn right (north). Then Supervisor. They will tone for a number above for any request for Contact Person: go one block to Pearl St. and turn right (east). driver and have the FRETAC the cache. 303-441-5852 Ambulance Cache delivered. Broomfield County North Metro Fire Directions for Pick-Up Activation Trailer Info Contact Info 303-438-6400 Broomfield Police The trailer is stored inside the fire Dispatch They will advise the on- NMFRD Station 67, 13875 S. -

Center for Public Safety Management Operational and Administrative Analysis, May 2021

CENTER OPERATIONALFOR PUBLIC SAFETY MANAGEMENT, AND LLC ADMINISTRATIVE ANALYSIS BILLINGS FIRE DEPARTMENT, BILLINGS, MONTANA Final Report-May 2021 CENTER FOR PUBLIC SAFETY MANAGEMENT, LLC 475 K STREET NW, STE 702 • WASHINGTON, DC 20001 WWW.CPSM.US • 716-969-1360 Exclusive Provider of Public Safety Technical Services for International City/County Management Association THE ASSOCIATION & THE COMPANY The International City/County Management Association is a 103-year-old nonprofit professional association of local government administrators and managers, with approximately 13,000 members located in 32 countries. Since its inception in 1914, ICMA has been dedicated to assisting local governments and their managers in providing services to its citizens in an efficient and effective manner. ICMA advances the knowledge of local government best practices with its website (www.icma.org), publications, research, professional development, and membership. The ICMA Center for Public Safety Management (ICMA/CPSM) was launched by ICMA to provide support to local governments in the areas of police, fire, and emergency medical services. ICMA also represents local governments at the federal level and has been involved in numerous projects with the Department of Justice and the Department of Homeland Security. In 2014, as part of a restructuring at ICMA, the Center for Public Safety Management (CPSM) was spun out as a separate company. It is now the exclusive provider of public safety technical assistance for ICMA. CPSM provides training and research for the Association’s members and represents ICMA in its dealings with the federal government and other public safety professional associations such as CALEA, PERF, IACP, IFCA, IPMA-HR, DOJ, BJA, COPS, NFPA, and others. -

View the Nationwide List of Thomas Fire Cooperating Agencies

THOMAS FIRE NATIONWIDE COOPERATING AGENCIES Alaska Alaska Fire Service Resources, Alaska Fire Service - Galena Zone, Mat-Su Area Forestry, Northern Region Office, Alaska Fire Service - Tanana Zone Arkansas Ouachita National Forest, Ozark & St. Francis National Forests Arizona Phoenix District, Flagstaff District, Tucson District, Arizona State Forestry - Central District, Arizona State Forestry - Northwest District, Avondale Fire Department, Alpine Fire District, Arizona Strip Field Office, Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest, Arizona State Forestry Division - State Office, Beaver Dam / Littlefield Fire District, Bisbee Fire Department, Bullhead City Fire Department, Benson Fire Department, Buckskin Fire District, Buckeye Fire Department, Central Arizona Fire and Medical Authority, Central Yavapai Fire District, Casa Grande Fire Department, Coronado National Forest, Coconino National Forest, Colorado River Agency, Daisy Mountain Fire Department, Arizona State Forestry Division - Deer Valley Office, Eloy Fire District, Fry Fire District, Gila District Office, Globe Fire Department, Green Valley Fire District, Golder Ranch Fire District, Greer Fire District, Heber-Overgaard Fire Department, Highlands Fire District, Kaibab National Forest, Mayer Fire District, Mohave Valley Fire Department, Navajo Region Fire and Aviation Management, North County Fire and Medical District, Nogales Fire Department, Northwest Fire Rescue District, Patagonia Volunteer Fire Department, Peoria Fire Department, Phoenix District Office, Picture Rocks Fire District, -

Fire & Emergency Medical Services Study City of New

FIRE & EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES STUDY CITY OF NEW BEDFORD (This is a draft and will be professionally formatted once finalized.) New Bedford Fire & Emergency Medical Services Study Draft Report – November 12, 2015 - Page 1 Table of Contents 1 - Executive Summary 2 - Study Process 3 - The New Bedford Community 4 – New Bedford Fire Department Services 5 – Fire and EMS Dispatch and Communications in New Bedford 6 – Fire and EMS Deployment Models 7 – New Bedford Emergency Medical Service 8 – EMS and Fire Department Budgets 9 – Benchmarking Against Other Communities 10 – Standards of Cover – New Bedford Fire Department 11 – Recommendations Glossary of Terms FACETS Team Members - Brief Biographies Listing of Tables and Figures Table 1 – Unemployment Rates in New Bedford, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and the United States Table 2 – Income Characteristics for New Bedford and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Table 3 – Land Use in New Bedford Table 4 – New Bedford Housing Characteristics Table 5 - New Bedford Fire Department Daily Staffing - April 2015 Table 6 - New Bedford Fire Incidents by Type and Year Table 7 - New Bedford Fires Table 8 – Percentage of False Alarms Table 9 – Marine Unit Responses Table 10 – Fire Permit Fees Table 11 – New Bedford EMS Unit Responses and Transports Table 12 – New Bedford EMS Expenditures and Revenue Table 13 – New Bedford Fire Department Expenditures Table 14 – Benchmark City Characteristics Table 15 – Benchmark Fire Department Resources Table 16 – Fire Department Actual Expenditures for 2014 Table 17 -

GACC Detailed Situation Report - by Protection

GACC Detailed Situation Report - by Protection Report Date: 09/25/2021 Geographic Area: Northern California Area Coordination Center Preparedness Level: IV 0 Wildfire Activity: Agency Unit Name Unit ID Fire P/ New New Uncntrld Human Human Lightning Lightning Total Total Acres Danger L Fires Acres Fires Fires Acres Fires Acres Fires (YTD) (YTD) (YTD) (YTD) BIA Hoopa Valley Tribe CA-HIA H 5 0 0 0 61 70 0 216 61 286 BIA 0 0 0 61 70 0 216 61 286 BLM Northern California District (CA-LNF) CA-NOD L 1 0 0 0 16 146.6 22 149.6 38 296.2 BLM 0 0 0 16 146.6 22 149.6 38 296.2 C&L Auburn Volunteer Fire Department CA-ABR N/R American Canyon Fire Protection District CA-ACY N/R Adin Fire Protection District CA-ADI N/R Anderson Fire Protection District CA-AFD N/R Alta Fire Protection District CA-AFP N/R Albion/Little River Volunteer Fire Department CA-ALR N/R Alturas City Fire Department CA-ALV N/R Annapolis Volunteer Fire Department CA-ANN N/R Arbuckle/College City Fire Protection District CA-ARB N/R Arcata Fire Protection District CA-ARF N/R Artois Fire Protection District CA-ART N/R Anderson Valley Fire Department CA-AVY N/R Bayliss Fire Protection District CA-BAY N/R Brooktrails Community Service District Fire Department CA-BCS N/R Bodega Bay Fire Protection District CA-BDB N/R Beckwourth Fire Protection District CA-BEC N/R Ben Lomond Fire Protection District CA-BEN N/R Sep 25, 2021 1 7:04:29 PM GACC Detailed Situation Report - by Protection Report Date: 09/25/2021 Geographic Area: Northern California Area Coordination Center Preparedness Level: IV -

Berthoud Fire Protection District CWPP Provides Guidance to Promote the Health, Safety and Welfare of the Community

BERTHOUD FIRE PROTECTION DISTRICT WILDLAND URBAN INTERFACE COMMUNITY WILDFIRE PROTECTION PLAN Prepared for: Berthoud Fire Protection District Berthoud, Colorado Submitted By: Anchor Point Boulder, Colorado September 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY OF THIS DOCUMENT...................................................................................................................... 1 THE NATIONAL FIRE PLAN............................................................................................................................... 1 PURPOSE............................................................................................................................................................ 2 GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ................................................................................................................................. 3 OTHER DESIRED OUTCOMES........................................................................................................................... 3 COLLABORATION: COMMUNITY/AGENCY/STAKEHOLDERS ...................................................................... 4 STUDY AREA OVERVIEW .................................................................................................................................. 5 VALUES AT RISK................................................................................................................................................ 9 LIFE SAFETY AND HOMES.....................................................................................................................................................9