The Delius Society Journal Autumn 2015, Number 158

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’

‘The Art-Twins of Our Timestretch’: Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’ Catherine Sarah Kirby Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Music (Musicology) April 2015 Melbourne Conservatorium of Music The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper Abstract This thesis explores Percy Grainger’s promotion of the music of Frederick Delius in the United States of America between his arrival in New York in 1914 and Delius’s death in 1934. Grainger’s ‘Delius campaign’—the title he gave to his work on behalf of Delius— involved lectures, articles, interviews and performances as both a pianist and conductor. Through this, Grainger was responsible for a number of noteworthy American Delius premieres. He also helped to disseminate Delius’s music by his work as a teacher, and through contact with publishers, conductors and the press. In this thesis I will examine this campaign and the critical reception of its resulting performances, and question the extent to which Grainger’s tireless promotion affected the reception of Delius’s music in the USA. To give context to this campaign, Chapter One outlines the relationship, both personal and compositional, between Delius and Grainger. This is done through analysis of their correspondence, as well as much of Grainger’s broader and autobiographical writings. This chapter also considers the relationship between Grainger, Delius and others musicians within their circle, and explores the extent of their influence upon each other. Chapter Two examines in detail the many elements that made up the ‘Delius campaign’. -

A Sound Invest~Ent J Arnes Fanzine

a sound invest~ent j arnes fanzine It's not until you've heard the music that you realise that James have narrated the story of your life. You know the songs because you've lived the song .. .. - James: Best of. ... a sound investment james fanzine issue#4 Issue #4 is finally out. We' ve been gone for a couple of years, but it a lm o ~ l fee ls like it's been longer (oh wait... It has been!) We apologize for our abscn · whi ch was mainly due to financial difficulties (we' ve had our own Bl ack Thurs day) and James being gone, but now that they're back in full force, we' ve dccldc ~l to put the zinc into gear and publish this issue. 1997 saw James cancel a number of shows in the States and England .... we hope that 1998 will bring renewed success to the band. At the time of printing, we hear that James wi ll have a greatest hits album that is due out in March J99K which will coincide with a short promo tour in the UK in mid· April. We also hc1 u that they wi ll have another album of new material released in late 1998. For current updates, check out the Internet sites which are continuously being updated as information is given. We hope you enjoy the zinc, it's been a lcutM time in the making .... if you are not on our mailing list, please send us your address/email. Also, let us know what you think (ie: do you want to sec m1ot hr1 issue?) Send us your comments and suggestions: LoriChin ChrisZych PO Box 251372 6088 Windemere Way Glendale, CA 91225-1372 Riverside, CA 92506 This issue is dedicated to ]ames Lawrence Gott. -

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers I-P JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) Born in Bowdon, Cheshire. He studied at the Royal College of Music with Stanford and simultaneously worked as a professional organist. He continued his career as an organist after graduation and also held a teaching position at the Royal College. Being also an excellent pianist he composed a lot of solo works for this instrument but in addition to the Piano Concerto he is best known for his for his orchestral pieces, especially the London Overture, and several choral works. Piano Concerto in E flat major (1930) Mark Bebbington (piano)/David Curti/Orchestra of the Swan ( + Bax: Piano Concertino) SOMM 093 (2009) Colin Horsley (piano)/Basil Cameron/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra EMI BRITISH COMPOSERS 352279-2 (2 CDs) (2006) (original LP release: HMV CLP1182) (1958) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra (rec. 1949) ( + The Forgotten Rite and These Things Shall Be) LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA LPO 0041 (2009) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Leslie Heward/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1942) ( + Moeran: Symphony in G minor) DUTTON LABORATORIES CDBP 9807 (2011) (original LP release: HMV TREASURY EM290462-3 {2 LPs}) (1985) Piers Lane (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/Ulster Orchestra ( + Legend and Delius: Piano Concerto) HYPERION CDA67296 (2006) John Lenehan (piano)/John Wilson/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend, First Rhapsody, Pastoral, Indian Summer, A Sea Idyll and Three Dances) NAXOS 8572598 (2011) MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 British & Commonwealth Concertos I-P Eric Parkin (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + These Things Shall Be, Legend, Satyricon Overture and 2 Symphonic Studies) LYRITA SRCD.241 (2007) (original LP release: LYRITA SRCS.36 (1968) Eric Parkin (piano)/Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend and Mai-Dun) CHANDOS CHAN 8461 (1986) Kathryn Stott (piano)/Sir Andrew Davis/BBC Symphony Orchestra (rec. -

The Delius Society Journal Spring 2001, Number 129

The Delius Society Journal Spring 2001, Number 129 The Delius Society (Registered Charity No. 298662) Full Membership and Institutions £20 per year UK students £10 per year US/\ and Canada US$38 per year Africa, Aust1alasia and far East £23 per year President Felix Aprahamian Vice Presidents Lionel Carley 131\, PhD Meredith Davies CBE Sir Andrew Davis CBE Vernon l Iandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Richard I Iickox FRCO (CHM) Lyndon Jenkins Tasmin Little f CSM, ARCM (I Ions), I Jon D. Lilt, DipCSM Si1 Charles Mackerras CBE Rodney Meadows Robc1 t Threlfall Chain11a11 Roge1 J. Buckley Trcaswc1 a11d M11111/Jrrship Src!l'taiy Stewart Winstanley Windmill Ridge, 82 Jlighgate Road, Walsall, WSl 3JA Tel: 01922 633115 Email: delius(alukonlinc.co.uk Serirta1y Squadron Lcade1 Anthony Lindsey l The Pound, Aldwick Village, West Sussex P021 3SR 'fol: 01243 824964 Editor Jane Armour-Chclu 17 Forest Close, Shawbirch, 'IC!ford, Shropshire TFS OLA Tel: 01952 408726 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.dclius.org.uk Emnil: [email protected]. uk ISSN-0306-0373 Ch<lit man's Message............................................................................... 5 Edilot ial....................... .... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... 6 ARTICLES BJigg Fair, by Robert Matthew Walker................................................ 7 Frede1ick Delius and Alf1cd Sisley, by Ray Inkslcr........... .................. 30 Limpsficld Revisited, by Stewart Winstanley....................................... 35 A Forgotten Ballet ?, by Jane Armour-Chclu -

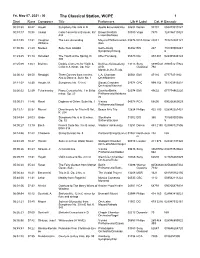

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Fri, May 07, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 30:47 Haydn Symphony No. 042 in D Apollo Ensemble/Hsu 02698 Dorian 90191 053479019127 00:33:1710:38 Vivaldi Cello Concerto in B minor, RV Brown/Scottish 03080 Virgo 7873 724356110328 424 Ensemble/Rees 00:44:5514:31 Vaughan The Lark Ascending Meyers/Philharmonia/L 03876 RCA Victor 23041 743212304121 Williams itton 01:00:5621:29 Nielsen Suite from Aladdin Gothenburg 06392 BIS 247 731859000247 Symphony/Chung 6 01:23:2501:14 Schubert The Youth at the Spring, D. Otter/Forsberg 05373 DG 453 481 028945348124 300 01:25:3933:03 Brahms Double Concerto for Violin & Bell/Isserlis/Academy 13113 Sony 88985321 889853217922 Cello in A minor, Op. 102 of St. Classical 792 Martin-in-the-Fields 02:00:1209:50 Respighi Three Dances from Ancient L.A. Chamber 00561 EMI 47116 07777471162 Airs & Dances, Suite No. 1 Orch/Marriner 02:11:02 14:30 Haydn, M. Symphony No. 12 in G Slovak Chamber 02578 CPO 999 154 761203915422 Orchestra/Warchal 02:26:3232:29 Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1 in B flat Gavrilov/Berlin 02074 EMI 49632 077774963220 minor, Op. 23 Philharmonic/Ashkena zy 03:00:3111:46 Ravel Daphnis et Chloe: Suite No. 1 Vienna 04578 RCA 68600 090266860029 Philharmonic/Maazel 03:13:1720:37 Mozart Divertimento for Trio in B flat, Beaux Arts Trio 12824 Philips 422 700 028942251427 K. 254 03:34:5424:03 Gade Symphony No. 6 in G minor, Stockholm 01002 BIS 355 731859000356 Op. -

James Runaground Mp3, Flac, Wma

James Runaground mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Runaground Country: UK Released: 1998 Style: Alternative Rock, Indie Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1538 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1174 mb WMA version RAR size: 1581 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 164 Other Formats: XM ADX AUD RA VQF MP2 AAC Tracklist 1 Runaground (Radio Edit) 3:49 Companies, etc. Record Company – PolyGram Produced For – Big Life Management Produced For – James Phonographic Copyright (p) – Mercury Records Ltd. (London) Copyright (c) – Mercury Records Ltd. (London) Published By – Polygram Music Publishing Ltd. Credits Backing Vocals – Michael Kulas Co-producer – Ott Design – Peacock Mixed By – Alan Douglas , Saul Davies Written-By – James Notes Plastic CD single case (6mm). Comes in a slimline jewelcase with a Jcard insert. Inner sleeve contains promo information on the band's upcoming April 1998 tour dates (mostly sold out) and mentions their The Best Of compilation which is 'already Gold in the U.K'. The Radio Edit here is slightly different to the finalised version of the track which featured on the retail CD singles and the aforementioned Best Of compilation; it is shorter and certain instrumentation sections are rearranged. 'Co-produced for Big Life Management & James' ℗ 1998 Mercury Records Ltd. The copyright in this sound recording is owned by Mercury Records Ltd. (London). © 1998 Mercury Records Ltd. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year JIMCD 20, 568 Runaground (CD, Single, Fontana, JIMCD 20, 568 James UK 1998 853-2 -

January 29, 2018: (Full-Page Version) Close Window “Where Is All the Knowledge We Lost with Information?” — T

January 29, 2018: (Full-page version) Close Window “Where is all the knowledge we lost with information?” — T. S. Eliot Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, 00:01 Buy Now! Franck The Breezes (A Symphonic Poem) National Orchestra of Belgium/Cluytens EMI Classics 13207 Awake! Welsh National Opera POLYGRAM 00:13 Buy Now! Delius In a Summer Garden, a Rhapsody 430202 28943020220 Orchestra/MacKerras RECORDS 00:28 Buy Now! Schumann Fantasy in C, Op. 17 Alan Marks Nimbus 5181 083603518127 01:00 Buy Now! Sibelius Night Ride and Sunrise, Op. 55 Philharmonia Orchestra/Rattle EMI 47006 N/A 01:16 Buy Now! Scarlatti, A. Sinfonia No. 7 in G minor for flute and strings Bennett/I Musici Philips 434 160 028943416023 01:24 Buy Now! Nielsen Violin Concerto, Op. 33 Lin/Swedish Radio Symphony/Salonen Sony 44548 07464445482 02:01 Buy Now! Strauss Jr. Emperor Waltz Vienna Philharmonic/Maazel DG 289 459 730 028945973029 02:13 Buy Now! Beethoven Minuets Nos. 1-4 Bella Musica Ensemble of Vienna Harmonia Mundi 1901017 3149021610175 02:22 Buy Now! Dvorak Piano Trio No. 1 in B flat, Op. 21 Suk Trio Denon 1409 T4988001077237 03:01 Buy Now! Vivaldi Flute Concerto in D, RV 90 "Il gardellino" Antonini/Il Giardino Armonico Milan Teldec 72367 090317326726 03:12 Buy Now! Rossini Overture ~ The Siege of Corinth Orchestra St. Cecilia/Pappano Warner Classics 0825646243440 825646243440 03:23 Buy Now! Reinecke Symphony No. 2 in C minor, Op. 134 "Hakon Jarl" Tasmanian Symphony/Shelley Chandos 9893 095115989326 04:00 Buy Now! Brahms Symphony No. -

Michigan Family Law Journal March 2016 Cations

M I C H IG A N FAMILY LAW JOURNAL A PUBLICATION OF THE STATE BAR OF MICHIGAN FAMILY LAW SECTION • CAROL F. BREITMEYER, CHAIR EDITOR: ANTHEA E. PAPISTA ASSISTANT EDITORS: SAHERA G. HOUSEY • LISA M. DAMPHOUSSE • RYAN M. O’ NEIL EDITORIAL BOARD: DANIEL B. BATES • AMY M. SPILMAN • SHELLEY R. SPIVACK • JAMES W. CHRYSSIKOS VOLUME 46 NUMBER 3 MARCH 2016 Chair Message ....................................................................... 1 By Carol F. Breitmeyer What’s Mine is Mine; WHAT’S YOURS IS MINE: Litigating SPECIAL THEME ISSUE Invasion of Separate Property Issues in Michigan............. 3 By Devin R. Day Evidence in Domestic Relations Cases ............................... 9 FAMILY LAW By Hon. Joseph J. Farah Persuasion Points: Becoming The Master Advocate Of LITIGATION The Core Message ............................................................... 14 By David C. Sarnacki Family Law Appellate Trends .............................................. 18 By Liisa R. Speaker Litigating Support Issues: Pass-Through Entities And K-1 Income ........................................................................... 23 By Kyle J. Quinn Family Law Arbitration: Successful Strategies & Tactics ................................................................................. 27 By James J. Harrington, III Litigation Involving the Valuation of a Parties’ Interest in a Closely Held Business ................................. 31 By Harvey I. Hauer and Mark A. Snover Leverage in Litigation ........................................................ 34 By -

Michigan Family Law Journal June/July 2015 FAMILY LAW SECTION MID-SUMMER CONFERENCE JULY 16 – 19, 2015 Boyne Mountain Resort

M I C H IG A N FAMILY LAW JOURNAL A PUBLICATION OF THE STATE BAR OF MICHIGan FAMILY LAW SECTION • REBECCA E. SHIEMKE, CHAIR EDITOR: ANTHEA E. PapISTA AssISTanT EDITORS: SAHERA G. HOUSEY • RYan M. O’ NEIL • LIsa M. DAMPHOUssE EDITORIAL BOARD: DanIEL B. BATES • AMY M. SPILMan • COLLEEN M. MARKOU • SHELLEY R. SPIvaCK • JAMES W. CHRYssIKOS VOLUME 45 NUMBER 6 JUNE/JULY 2015 Chair Message: Mediator Standards of Conduct and the Importance of Screening ........1 By Rebecca E. Shiemke Notice Proposed Amendments of the Bylaws of the Family Law Section of the State Bar of Michigan ..................................................................4 Family Law Council Elections October 8, 2015 ..5 The Case of the Issue ..............................................8 By Henry S. Gornbein The 12 Steps of Mediation ...................................12 By Shon Cook Professor Lex .........................................................13 By Harvey I. Hauer and Mark A. Snover Residence Roulette in the Jurisdiction Jungle: Where To Divide The Pension?.............................15 By Mark Sullivan Tailored Installment Payments to Balance the Scales without Breaking the Bank .....................19 By Joseph W. Cunningham Recent Appellate Decisions .................................22 Summarized by the State Bar Family Law Section Amicus Committee Members Legislative Update ................................................27 By William Kandler Advertise in the Photograph On the Cover M I C H IG A N The photo on the front cover is Michigan’s State Capitol as FAMILY LAW photographed in May 2015 from the OURNAL 14th floor of the Romney Building. J The photographer, Ken Randall, is the Midland County Friend of the Court. Ten times per year, the Michigan Family Law Journal Ken is both a lawyer and an artist. -

A Conductor's Guide to Twentieth-Century Choral-Orchestral Works in English

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9314580 A conductor's guide to twentieth-century choral-orchestral works in English Green, Jonathan David, D.M.A. The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 1992 UMI 300 N. -

United States Premieres

United States Premieres Composer Work Date Conductor Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 2 22-Apr 1843 Boucher/Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Piano and Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Dramatic Poem, Manfred Brahms Serenade No. 2 in A major for Small Orchestra, 1-Feb 1862 Bergmann Op. 16 Berlioz First four movements from Symphonie 27-Jan 1866 Bergmann fantastique: episode de la vie d'un artiste (Fantastic Symphony: Episode in the Life of an Artist) Gade Hamlet 28-Nov 1868 Bergmann Liszt Poème symphonique 9-Jan 1869 Bergmann R.