DSJ 140 Autumn 2006.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KENNETH HAMILTON Plays RONALD STEVENSON VOLUME 2

RS2 Booklet_BOOKLET24 11/06/2019 14:32 Page 1 KENNETH HAMILTON plays RONALD STEVENSON VOLUME 2 16 1 RS2 Booklet_BOOKLET24 11/06/2019 14:32 Page 2 Kenneth Hamilton Plays Ronald Stevenson, Volume 2 Kenneth Hamilton Described after a concerto performance with the St Petersburg State Symphony Orchestra as “an outstanding virtuoso- Kenneth Hamilton (Piano) one of the finest players of his generation” (Moscow Kommersant ), by the Singapore Straits Times as ‘a formidable Ronald Stevenson (1928-2015): virtuoso’; and by Tom Service in The Guardian as “pianist, author, lecturer and all-round virtuoso”, Scottish pianist Kenneth Hamilton performs worldwide. He has appeared frequently on radio and television, including a performance 1 Keening Song for a Makar (in memoriam Francis George Scott) 7.19 of Chopin’s first piano concerto with the Istanbul Chamber Orchestra on Turkish Television, and a dual role as pianist 2 Norse Elegy for Ella Nygard 6.01 and presenter for the television programme Mendelssohn in Scotland , broadcast in Europe and the US by Deutsche Welle Channel. He is a familiar presence on BBC Radio 3, and has numerous international festival engagements to his credit. 3 Chorale-Pibroch for Sorley Maclean 6.11 4 Toccata-Reel: “The High Road to Linton” 2.31 His recent recordings for the Prima Facie label: Volume 1 of Kenneth Hamilton Plays Ronald Stevenson, Back to Bach: 5 Barra Flyting Toccata 1.32 Tributes and Transcriptions by Liszt, Rachmaninov and Busoni , and Preludes to Chopin have been greeted with widespread critical acclaim: “played with understanding and brilliance” (Andrew McGregor, BBC Radio 3 Record 6 Merrick/Stevenson: Hebridean Seascape 11.00 Review); “an unmissable disk… fascinating music presented with power, passion and precision” (Colin Clarke, 7 Little Jazz Variations on Purcell’s “New Scotch Tune” 5.03 Fanfare);“precise control and brilliance” (Andrew Clements, The Guardian ); “thrilling” (Jeremy Nicholas, 8 Threepenny Sonatina (on Kurt Weill’s Threepenny Opera)* 5.51 Gramophone ). -

Boosey & Hawkes

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Howell, Jocelyn (2016). Boosey & Hawkes: The rise and fall of a wind instrument manufacturing empire. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City, University of London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/16081/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Boosey & Hawkes: The Rise and Fall of a Wind Instrument Manufacturing Empire Jocelyn Howell PhD in Music City University London, Department of Music July 2016 Volume 1 of 2 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................... 2 Table of Figures...................................................................................................................................... -

The Delius Society Journal Autumn 2016, Number 160

The Delius Society Journal Autumn 2016, Number 160 The Delius Society (Registered Charity No 298662) President Lionel Carley BA, PhD Vice Presidents Roger Buckley Sir Andrew Davis CBE Sir Mark Elder CBE Bo Holten RaD Piers Lane AO, Hon DMus Martin Lee-Browne CBE David Lloyd-Jones BA, FGSM, Hon DMus Julian Lloyd Webber FRCM Anthony Payne Website: delius.org.uk ISSN-0306-0373 THE DELIUS SOCIETY Chairman Position vacant Treasurer Jim Beavis 70 Aylesford Avenue, Beckenham, Kent BR3 3SD Email: [email protected] Membership Secretary Paul Chennell 19 Moriatry Close, London N7 0EF Email: [email protected] Journal Editor Katharine Richman 15 Oldcorne Hollow, Yateley GU46 6FL Tel: 01252 861841 Email: [email protected] Front and back covers: Delius’s house at Grez-sur-Loing Paintings by Ishihara Takujiro The Editor has tried in good faith to contact the holders of the copyright in all material used in this Journal (other than holders of it for material which has been specifically provided by agreement with the Editor), and to obtain their permission to reproduce it. Any breaches of copyright are unintentional and regretted. CONTENTS EDITORIAL ..........................................................................................................5 COMMITTEE NOTES..........................................................................................6 SWEDISH CONNECTIONS ...............................................................................7 DELIUS’S NORWEGIAN AND DANISH SONGS: VEHICLES OF -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

FOMRHI Quarterly

_. " Elena Dal Cortiv& No. 45 October 1986 FOMRHI Quarterly BULLETIN 45 2 Bulletin Supplement 8 Plans: Bate Collection 9 Plans? The Royal College of Music 12 Membership List Supplement 45 COMMUNICATIONS 745- REVIEWS: Dirtionnaire des facteurs d'instruments ..., by M. Haine £ 748 N. Meeus', Musical Instruments in the 1851 Exhibition, by P. £ A. Mactaggart; Samuel Hughes Ophideidist, by S. J, Weston} Chanter! The Journal of the Bagpipe Sodiety, vol.1, part 1 J. Montagu 14 749 New Grove DoMi: JM 65 Further Detailed Comments: The Gs. J. Montagu 18 750 New Grove DoMi: ES no. 6J D Entries E. Segerman 23 751 More on Longman, Lukey £ Broderip J. Montagu 25 752 Made for music—the Galpin Sodety's 40th anniversary J. Montagu 26 753 Mersenne, Mace and speed of playing E. Segerman 29 754' A bibliography of 18th century sources relating to crafts, manufacturing and technology T. N. McGeary 31 755 What has gone wrong with the Early Music movement? B. Samson 36 / B. Samson 37 756 What is a 'simple' lute? P. Forrester 39 757 A reply to Comm 742 D. Gill 42 758 A follow-on to Comm 739 H. Hope 44 759 (Comments on the chitarra battente) B. Barday 47 760 (Craftsmanship of Nurnberg horns) K. Williams 48 761 Bore gauging - some ideas and suggestions C. Karp 50 7632 Woodwin(On measurind borge toolmeasurins and gmodems tools ) C. Stroom 55 764 A preliminary checklist of iconography for oboe-type instruments, reeds, and players, cl630-cl830 B. Haynes 58 765 Happy, happy transposition R. Shann 73 766 The way from Thoiry to Nuremberg R. -

Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’

‘The Art-Twins of Our Timestretch’: Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’ Catherine Sarah Kirby Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Music (Musicology) April 2015 Melbourne Conservatorium of Music The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper Abstract This thesis explores Percy Grainger’s promotion of the music of Frederick Delius in the United States of America between his arrival in New York in 1914 and Delius’s death in 1934. Grainger’s ‘Delius campaign’—the title he gave to his work on behalf of Delius— involved lectures, articles, interviews and performances as both a pianist and conductor. Through this, Grainger was responsible for a number of noteworthy American Delius premieres. He also helped to disseminate Delius’s music by his work as a teacher, and through contact with publishers, conductors and the press. In this thesis I will examine this campaign and the critical reception of its resulting performances, and question the extent to which Grainger’s tireless promotion affected the reception of Delius’s music in the USA. To give context to this campaign, Chapter One outlines the relationship, both personal and compositional, between Delius and Grainger. This is done through analysis of their correspondence, as well as much of Grainger’s broader and autobiographical writings. This chapter also considers the relationship between Grainger, Delius and others musicians within their circle, and explores the extent of their influence upon each other. Chapter Two examines in detail the many elements that made up the ‘Delius campaign’. -

Journal83-1.Pdf

The Delius Society Journal July 1984',Number 83 The DeliusSociety Full Membershipf,8.00 per year Studentsf,5.00 Subscriptionto Libraries(Journal only) f,6.00 per year USA and CanadaUS $ 17.00 per year President Eric Fenby OBE, Hon D Mus, Hon D Litt, Hon RAM Vice Presidents The Rt Hon Lord Boothby KBE, LLD Felix AprahamianHon RCO Roland GibsonM Sc,Ph D (FounderMember) Sir CharlesGroves CBE Stanford RobinsonOBE, ARCM (Hon), Hon CSM MeredithDavies CBE, MA, B Mus, FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE, Hon D Mus Vernon Handley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse, Mount Park Road,Harrow, Middlesex Treasurer Peter Lyons 160 WishingTree Road, St. Leonards-on-Sea,East Sussex Secretary Miss Diane Eastwood 28 Emscote Street South, Bell Hall, Halifax, Yorkshire Tel: (0422) 50537 Editor StephenLloyd 85aFarley Hill, Luton,Bedfordshire LUI 5EG Tel: Luton (0582)20075 Contents Editoria! 'Delius as they saw him' by Robert Threlfall Kenneth Spenceby Lionel Hill t9 Margot La Rouge at Camden Festival 2l RPS Sir John Barbirolli concert 23 Midlands Branch meetins: Arnold Bax 24 Cynara in the Midlands 24 Midlands Branch meeting: an eveningof film 25 Forthcoming Events 26 Acknowledgements The cover illustration is an early sketchof Delius by Edvard Munch (no. 1 in Robert Threlfall's Iconography,see page 7), reproducedby kind per- missionof the Curator of the Munch Museum, Oslo. The photographicplates in this issuehave been financed by a legacyto the Delius Societyfrom the late Robert Aickman. The photographson pp. 8, 9 and 17 are reproduced by kind permission of Andrew Boyle with acknowledgementto Lionel Carley, the owner of the two heads.The two photographson page 13were taken by the Editor with the permissionof Denis Blood. -

A Sound Invest~Ent J Arnes Fanzine

a sound invest~ent j arnes fanzine It's not until you've heard the music that you realise that James have narrated the story of your life. You know the songs because you've lived the song .. .. - James: Best of. ... a sound investment james fanzine issue#4 Issue #4 is finally out. We' ve been gone for a couple of years, but it a lm o ~ l fee ls like it's been longer (oh wait... It has been!) We apologize for our abscn · whi ch was mainly due to financial difficulties (we' ve had our own Bl ack Thurs day) and James being gone, but now that they're back in full force, we' ve dccldc ~l to put the zinc into gear and publish this issue. 1997 saw James cancel a number of shows in the States and England .... we hope that 1998 will bring renewed success to the band. At the time of printing, we hear that James wi ll have a greatest hits album that is due out in March J99K which will coincide with a short promo tour in the UK in mid· April. We also hc1 u that they wi ll have another album of new material released in late 1998. For current updates, check out the Internet sites which are continuously being updated as information is given. We hope you enjoy the zinc, it's been a lcutM time in the making .... if you are not on our mailing list, please send us your address/email. Also, let us know what you think (ie: do you want to sec m1ot hr1 issue?) Send us your comments and suggestions: LoriChin ChrisZych PO Box 251372 6088 Windemere Way Glendale, CA 91225-1372 Riverside, CA 92506 This issue is dedicated to ]ames Lawrence Gott. -

The War to End War — the Great War

GO TO MASTER INDEX OF WARFARE GIVING WAR A CHANCE, THE NEXT PHASE: THE WAR TO END WAR — THE GREAT WAR “They fight and fight and fight; they are fighting now, they fought before, and they’ll fight in the future.... So you see, you can say anything about world history.... Except one thing, that is. It cannot be said that world history is reasonable.” — Fyodor Mikhaylovich Dostoevski NOTES FROM UNDERGROUND “Fiddle-dee-dee, war, war, war, I get so bored I could scream!” —Scarlet O’Hara “Killing to end war, that’s like fucking to restore virginity.” — Vietnam-era protest poster HDT WHAT? INDEX THE WAR TO END WAR THE GREAT WAR GO TO MASTER INDEX OF WARFARE 1851 October 2, Thursday: Ferdinand Foch, believed to be the leader responsible for the Allies winning World War I, was born. October 2, Thursday: PM. Some of the white Pines on Fair Haven Hill have just reached the acme of their fall;–others have almost entirely shed their leaves, and they are scattered over the ground and the walls. The same is the state of the Pitch pines. At the Cliffs I find the wasps prolonging their short lives on the sunny rocks just as they endeavored to do at my house in the woods. It is a little hazy as I look into the west today. The shrub oaks on the terraced plain are now almost uniformly of a deep red. HDT WHAT? INDEX THE WAR TO END WAR THE GREAT WAR GO TO MASTER INDEX OF WARFARE 1914 World War I broke out in the Balkans, pitting Britain, France, Italy, Russia, Serbia, the USA, and Japan against Austria, Germany, and Turkey, because Serbians had killed the heir to the Austrian throne in Bosnia. -

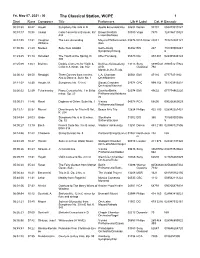

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Fri, May 07, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 30:47 Haydn Symphony No. 042 in D Apollo Ensemble/Hsu 02698 Dorian 90191 053479019127 00:33:1710:38 Vivaldi Cello Concerto in B minor, RV Brown/Scottish 03080 Virgo 7873 724356110328 424 Ensemble/Rees 00:44:5514:31 Vaughan The Lark Ascending Meyers/Philharmonia/L 03876 RCA Victor 23041 743212304121 Williams itton 01:00:5621:29 Nielsen Suite from Aladdin Gothenburg 06392 BIS 247 731859000247 Symphony/Chung 6 01:23:2501:14 Schubert The Youth at the Spring, D. Otter/Forsberg 05373 DG 453 481 028945348124 300 01:25:3933:03 Brahms Double Concerto for Violin & Bell/Isserlis/Academy 13113 Sony 88985321 889853217922 Cello in A minor, Op. 102 of St. Classical 792 Martin-in-the-Fields 02:00:1209:50 Respighi Three Dances from Ancient L.A. Chamber 00561 EMI 47116 07777471162 Airs & Dances, Suite No. 1 Orch/Marriner 02:11:02 14:30 Haydn, M. Symphony No. 12 in G Slovak Chamber 02578 CPO 999 154 761203915422 Orchestra/Warchal 02:26:3232:29 Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1 in B flat Gavrilov/Berlin 02074 EMI 49632 077774963220 minor, Op. 23 Philharmonic/Ashkena zy 03:00:3111:46 Ravel Daphnis et Chloe: Suite No. 1 Vienna 04578 RCA 68600 090266860029 Philharmonic/Maazel 03:13:1720:37 Mozart Divertimento for Trio in B flat, Beaux Arts Trio 12824 Philips 422 700 028942251427 K. 254 03:34:5424:03 Gade Symphony No. 6 in G minor, Stockholm 01002 BIS 355 731859000356 Op. -

James Runaground Mp3, Flac, Wma

James Runaground mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Runaground Country: UK Released: 1998 Style: Alternative Rock, Indie Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1538 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1174 mb WMA version RAR size: 1581 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 164 Other Formats: XM ADX AUD RA VQF MP2 AAC Tracklist 1 Runaground (Radio Edit) 3:49 Companies, etc. Record Company – PolyGram Produced For – Big Life Management Produced For – James Phonographic Copyright (p) – Mercury Records Ltd. (London) Copyright (c) – Mercury Records Ltd. (London) Published By – Polygram Music Publishing Ltd. Credits Backing Vocals – Michael Kulas Co-producer – Ott Design – Peacock Mixed By – Alan Douglas , Saul Davies Written-By – James Notes Plastic CD single case (6mm). Comes in a slimline jewelcase with a Jcard insert. Inner sleeve contains promo information on the band's upcoming April 1998 tour dates (mostly sold out) and mentions their The Best Of compilation which is 'already Gold in the U.K'. The Radio Edit here is slightly different to the finalised version of the track which featured on the retail CD singles and the aforementioned Best Of compilation; it is shorter and certain instrumentation sections are rearranged. 'Co-produced for Big Life Management & James' ℗ 1998 Mercury Records Ltd. The copyright in this sound recording is owned by Mercury Records Ltd. (London). © 1998 Mercury Records Ltd. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year JIMCD 20, 568 Runaground (CD, Single, Fontana, JIMCD 20, 568 James UK 1998 853-2 -

Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings Of

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 5-May-2010 I, Mary L Campbell Bailey , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in Oboe It is entitled: Léon Goossens’s Impact on Twentieth-Century English Oboe Repertoire: Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings of Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Sonata for Oboe of York Bowen Student Signature: Mary L Campbell Bailey This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Mark Ostoich, DMA Mark Ostoich, DMA 6/6/2010 727 Léon Goossens’s Impact on Twentieth-century English Oboe Repertoire: Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings of Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Sonata for Oboe of York Bowen A document submitted to the The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 24 May 2010 by Mary Lindsey Campbell Bailey 592 Catskill Court Grand Junction, CO 81507 [email protected] M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2004 B.M., University of South Carolina, 2002 Committee Chair: Mark S. Ostoich, D.M.A. Abstract Léon Goossens (1897–1988) was an English oboist considered responsible for restoring the oboe as a solo instrument. During the Romantic era, the oboe was used mainly as an orchestral instrument, not as the solo instrument it had been in the Baroque and Classical eras. A lack of virtuoso oboists and compositions by major composers helped prolong this status. Goossens became the first English oboist to make a career as a full-time soloist and commissioned many British composers to write works for him.