RED ALDER Northwest Extracted a Red Dye from the Inner Bark, Which Was Used to Dye Fishnets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Note 37: Identification, Ecology, Use, and Culture of Sitka

TECHNICAL NOTES _____________________________________________________________________________________________ US DEPT. OF AGRICULTURE NATURAL RESOURCES CONSERVATION SERVICE Portland, OR April 2005 PLANT MATERIALS No. 37 Identification, Ecology, Use and Culture of Sitka Alder Dale C. Darris, Conservation Agronomist, Corvallis Plant Materials Center Introduction Sitka alder [Alnus viridis (Vill.) Lam. & DC. subsp. sinuata (Regel) A.& D. Löve] is a native deciduous shrub or small tree that grows to height of 20 ft, occasionally taller. Although a non-crop species, it has several characteristics useful for reclamation, forestry, and erosion control. The species is known for abundant leaf litter production, the fixation of atmospheric nitrogen in association with Frankia bacteria, and a strong fibrous root system. Where locally abundant, it naturally colonizes landslide chutes, areas of stream scour and deposition, soil slumps, and other drastic disturbances resulting in exposed minerals soils. These characteristics make Sitka alder particularly useful for streambank stabilization and soil building on impoverished sites. In addition, its low height and early slowdown in growth rate makes it potentially more desirable than red alder (Alnus rubra) to interplant with conifers such as Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menzieii) and lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta) where soil fertility is moderate to low. However, high densities can hinder forest regeneration efforts. The species may also be useful as a fast growing shrub row in field windbreaks. Sitka alder is most abundant at mid to subalpine elevations. Low elevation seed sources (below 100 m) are uncommon but probably provide the best material for reclamation and erosion control projects on valley floors and terraces. Distribution and Identification Sitka alder (Alnus viridis subsp. sinuata) is a native deciduous shrub or small tree that grows to a height of 1-6 m (3-19 ft) in the mountains and 6-12 m (19-37ft) at low elevations. -

TREES HAVE HIGHER LONGITUDINAL GROWTH STRAINS in THEIR STEMS THAN in THEIR ROOTS in the Secondary Xylem of Trees, Each Wood Cell

a3q14 Int. 1. Plant Sci. 158(4):418-423. 1997. © 1997 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. 1058-5893/97/5804-0003$03.00 TREES HAVE HIGHER LONGITUDINAL GROWTH STRAINS IN THEIR STEMS THAN IN THEIR ROOTS BARBARA L. GARTNER Department of Forest Products, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97 33 1-7402 Longitudinal growth strains develop in woody tissues during cell-wall formation. This study compares stems, which have a mechanical role and experience longitudinal stresses, and nonstructural roots, which have little mechanical role and experience few or no longitudinal stresses, to test the hypothesis that growth strains are produced in stems of straight trees as an adaptive feature for mechanical loads. I measured growth strains in one stem (at breast height) and one nonstructural root (beyond the zone of rapid taper and/or beyond a major change in root direction) for 13-15 individuals of each of four tree species, Pseudotsuga menziesii, Thuja heterophylla, Acer macrophyllum, and Alnus rubra. Forty-seven of the 54 individuals had higher strains in their stems than in their roots (4.3 ± 0.3 x 10- 4 and 1.5 ± 0.3 x 10-4, respectively). Growth strain was two to five times higher for stems than roots. The modulus of elasticity (MOE) in bending was also higher in stem tissues (from literature values) than in root tissue (from this study). Calculated growth stresses, the product of growth strain and MOE, averaged 6-11 times higher in stems than roots for the four species. The higher strain and stress in stems than roots indicate that the strains and stresses are adaptive features that are produced in response to, or in "anticipation," of mechanical loads. -

Nitrogen Transformations in Soils Beneath Red Alder and Conifers

From Biology of Alder ERTY OF: Proceedings of Northwest Scientific Association Annual Mee t4■::::),...;ADE HEAD EXPERIMENTAL FOREST April 14-15, 1967 Published 1968 AND SCENIC RESEARCH AREA OTIS, OREGON Nitrogen transformations in soils beneath red alder and conifers W. B. Bollen, Abstract Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon Transformations of nitrogen in organic matter in the soil are essential to and plant nutrition because nitrogen in the form of proteins and other organic K. C. Lu compounds is not directly available. These compounds must undergo Forestry Sciences Laboratory microbial decomposition to liberate nitrogen as ammonium (NH -I-4) and Pacific Northwest Forest nitrate (NO3 ), which can then be absorbed by plant roots. and Range Experiment Station Nitrogen transformations, particularly nitrification, are rapid in soils under Corvallis, Oregon coastal Oregon stands of red alder (Alnus rubra Bong.); conifers — Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco), western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla Raf) Sarg.), and Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis (Bong.) Carr.); and mixed stands of alder and conifers. Nitrification is especially rapid in the F layer beneath alder stands despite a very low pH. These findings are from a study of contributions to the nitrogen economy by red alder conducted at Cascade Head Experimental Forest near Otis, Oregon (Chen, 1965). 1 Procedures Ammonifying capacity of the different samples was compared by testing duplicate 50-g portions, ovendry basis, of each with peptone equivalent to 1,000 ppm nitrogen. These samples, and samples of untreated soil, were incubated for 35 days at 28 C. Moisture was adjusted to 50 percent of the water- holding capacity. At the close of incubation, each sample was analyzed for NH+4, NO-2, and NO-3 nitrogen and for pH. -

University of California Santa Cruz Responding to An

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ RESPONDING TO AN EMERGENT PLANT PEST-PATHOGEN COMPLEX ACROSS SOCIAL-ECOLOGICAL SCALES A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES with an emphasis in ECOLOGY AND EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY by Shannon Colleen Lynch December 2020 The Dissertation of Shannon Colleen Lynch is approved: Professor Gregory S. Gilbert, chair Professor Stacy M. Philpott Professor Andrew Szasz Professor Ingrid M. Parker Quentin Williams Acting Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Shannon Colleen Lynch 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables iv List of Figures vii Abstract x Dedication xiii Acknowledgements xiv Chapter 1 – Introduction 1 References 10 Chapter 2 – Host Evolutionary Relationships Explain 12 Tree Mortality Caused by a Generalist Pest– Pathogen Complex References 38 Chapter 3 – Microbiome Variation Across a 66 Phylogeographic Range of Tree Hosts Affected by an Emergent Pest–Pathogen Complex References 110 Chapter 4 – On Collaborative Governance: Building Consensus on 180 Priorities to Manage Invasive Species Through Collective Action References 243 iii LIST OF TABLES Chapter 2 Table I Insect vectors and corresponding fungal pathogens causing 47 Fusarium dieback on tree hosts in California, Israel, and South Africa. Table II Phylogenetic signal for each host type measured by D statistic. 48 Table SI Native range and infested distribution of tree and shrub FD- 49 ISHB host species. Chapter 3 Table I Study site attributes. 124 Table II Mean and median richness of microbiota in wood samples 128 collected from FD-ISHB host trees. Table III Fungal endophyte-Fusarium in vitro interaction outcomes. -

Alder Canopy Dieback and Damage in Western Oregon Riparian Ecosystems

Alder Canopy Dieback and Damage in Western Oregon Riparian Ecosystems Sims, L., Goheen, E., Kanaskie, A., & Hansen, E. (2015). Alder canopy dieback and damage in western Oregon riparian ecosystems. Northwest Science, 89(1), 34-46. doi:10.3955/046.089.0103 10.3955/046.089.0103 Northwest Scientific Association Version of Record http://cdss.library.oregonstate.edu/sa-termsofuse Laura Sims,1, 2 Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Oregon State University, 1085 Cordley Hall, Corvallis, Oregon 97331 Ellen Goheen, USDA Forest Service, J. Herbert Stone Nursery, Central Point, Oregon 97502 Alan Kanaskie, Oregon Department of Forestry, 2600 State Street, Salem, Oregon 97310 and Everett Hansen, Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, 1085 Cordley Hall, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97331 Alder Canopy Dieback and Damage in Western Oregon Riparian Ecosystems Abstract We gathered baseline data to assess alder tree damage in western Oregon riparian ecosystems. We sought to determine if Phytophthora-type cankers found in Europe or the pathogen Phytophthora alni subsp. alni, which represent a major threat to alder forests in the Pacific Northwest, were present in the study area. Damage was evaluated in 88 transects; information was recorded on damage type (pathogen, insect or wound) and damage location. We evaluated 1445 red alder (Alnus rubra), 682 white alder (Alnus rhombifolia) and 181 thinleaf alder (Alnus incana spp. tenuifolia) trees. We tested the correlation between canopy dieback and canker symptoms because canopy dieback is an important symptom of Phytophthora disease of alder in Europe. We calculated the odds that alder canopy dieback was associated with Phytophthora-type cankers or other biotic cankers. -

Brotherella Roellii (Renauld & Cardot) M

Brotherella roellii (Renauld & Cardot) M. Fleisch. Roll's golden log moss Sematophyllaceae status: State Threatened, USFS strategic rank: G3 / SH General Description: Shiny golden to yellowish green moss forming thin, small carpets. Stems lying flat, creeping, branching irregularly, 0.5-3 cm x 0.5-1 mm. Leaves 0.8-1.2 mm long, often turned to one side, ovate-lanceolate, tip pointed, concave. Costa lacking, or double and very short. Alar cells strongly inflated. Outer layer of stem cells (cortical cells) are inflated, colorless, transparent, and larger than the interior cells. There is often a row of enlarged cells extending across the leaf base. Reproductive Characteristics: Produces male and female sex organs on the same plant but in separate locations. Seta 0.6-1 cm long. Capsule erect to somewhat inclined, straight or slightly asymmetric. Urn 1-1.5 mm long. Operculum long and narrow, up to 1 mm long. Identification Tips: Hypnum circinale is a similar species that often grows in the same habitat. However, it is a larger moss, dull grayish to bluish green in color, with longer leaves (up to 2.2 mm) that are slightly to strongly curved nearly into a circle. It has only a few slightly inflated quadrate to rectangular, alar cells; its cortical cells are small and thick-walled. In contrast, B. roellii has strongly inflated alar cells, and large, thin-walled, inflated cortical cells. Range: Endemic to southwestern B.C. and WA. Habitat/Ecology: Forms small, glossy, green to golden yellow mats, usually on old logs and other rotten wood; also © Judy Harpel on the bases of red alder (Alnus rubra) and other hardwood trees. -

Vegetation Mapping of the Mckenzie Preserve at Table Mountain and Environs, Southern Sierra Nevada Foothills, California

Vegetation Mapping of the McKenzie Preserve at Table Mountain and Environs, Southern Sierra Nevada Foothills, California By Danielle Roach, Suzanne Harmon, and Julie Evens Of the 2707 K Street, Suite 1 Sacramento CA, 95816 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To Those Who Generously Provided Support and Guidance: Many groups and individuals assisted us in completing this report and the supporting vegetation map/data. First, we expressly thank an anonymous donor who provided financial support in 2010 for this project’s fieldwork and mapping in the southern foothills of the Sierra Nevada. We also are thankful of the generous support from California Department of Fish and Game (DFG) in funding 2008 field survey work in the region. We are indebted to the following additional staff and volunteers of the California Native Plant Society who provided us with field surveying, mission planning, technical GIS, and other input to accomplish this project: Jennifer Buck, Andra Forney, Andrew Georgeades, Brett Hall, Betsy Harbert, Kate Huxster, Theresa Johnson, Claire Muerdter, Eric Peterson, Stu Richardson, Lisa Stelzner, Aaron Wentzel, and in particular, Kendra Sikes. To Those Who Provided Land Access: Joanna Clines, Forest Botanist, USDA Forest Service, Sierra National Forest Ellen Cypher, Botanist, Department of Fish and Game, Region 4 Mark Deleon, Supervising Ranger, Millerton Lake State Recreation Area Bridget Fithian, Mariposa Program Manager, Sierra Foothill Conservancy Coke Hallowell, Private landowner, San Joaquin River Parkway & Conservation Trust Wayne Harrison, California State Parks, Central Valley District Chris Kapheim, General Manager, Alta Irrigation District Denis Kearns, Botanist, Bureau of Land Management Melinda Marks, Executive Officer, San Joaquin River Conservancy Nathan McLachlin, Scientific Aid, Department of Fish and Game, Region 4 Eddie and Gail McMurtry, private landowners Chuck Peck, Founder, Sierra Foothill Conservancy Kathyrn Purcell, Research Wildlife Ecologist, San Joaquin Experimental Range, USDA Forest Service Carrie Richardson, Senior Ranger, U.S. -

Stream & Wetland Enhancement Guide

Stream & Wetland Enhancement Guide Department of Community Development (541) 488-5305 www.ashland.or.us Stream & Wetland Enhancement Guide A healthy network of urban streams and wetlands protects water quality, reduces flood- ing impacts, provides fish and wildlife habitat, and enhances the beauty and livability of our community. You can help protect and enhance these important natural resources by learning the techniques outlined in this guide. These techniques will help you control erosion, man- age invasive plants, and cultivate a healthy, native landscape. This guide is arranged into sections to help you understand, design, plant and manage streamside vegetation. For more information about how you can protect your neighborhood streams and wet- lands, and find out about regulations pertaining to the alteration of riparian and wetland habitats contact the City of Ashland Department of Community Development at (541) 488-5305 or visit the City’s web page dedicated to Water Resources: www.ashland.or.us/waterresources Stream & Wetland Enhancement Guide Contents 1. Water Protection Zones Streams and Wetlands (pgs. 1-4) 2. Rogue Basin Native Plants (pgs. 5-6) 3. Noxious and Plants (pgs. 7-8) 4. Planting and Managing Streamside Vegetation (pgs. 9-11) 5. Planting Techniques (pg. 12) 6. Plant Protection (pg. 13) 7.Streamside Stabilization and Erosion Control (pgs. 14-16) 8. Plant Communities Riparian Woodland (pg. 17) Wetland (pg. 18) 9. Use of Herbicides (pgs. 19-20) 10. Additional Resources (pg. 21) 1. Water Resource Protection Zones - Streams A riparian area is the area of land adjacent to a stream. Healthy riparian areas reduce the chance of damaging floods, improve water quality and provide habitat and food for fish and wildlife. -

KLMN Featured Creature White Alder

National Park Service Featured Creature U.S. Department of the Interior January 2020 Klamath Network Inventory & Monitoring Division Natural Resource Stewardship & Science White Alder Alnus rhombifolia General Description Reproduction As early as January, when many trees are still White alders can reproduce by seed or veg- dormant, you might find yourself sneezing etatively from the roots. For reproduction by through a cloud of white alder pollen. Alders seed, both male and female flowers grow on a are members of the birch family (Betulaceae), single white alder tree, making it monoecious NPS photo and several species of alder grow natively in (meaning “single house”). The new reproduc- North America, typically near streams. tive cycle actually begins in the summer or fall White alder leaves and female catkins. before the next spring’s bloom, when clusters The white alder, Alnus rhombifolia, also called (catkins) of female flowers begin developing pileated woodpeckers or red-breasted nut- the California alder, is an inland tree of the as a small roundish green growth. Yellowish hatches sometimes nest in white alders. Cascade and Sierra Nevada mountain ranges, male flower clusters (catkins) form into long closely related to but not often overlapping (3–10 cm; 1.2–3.9 in) slender, drooping cylin- Alders have a handy adaptation not often its more coastal cousin, the red alder (Alnus ders that don’t release their pollen until early seen outside of the legume family: they can rubra). It sports dark green, glossy leaves with spring (Jan–Apr). Neither flower is showy, “fix” the vital plant nutrient, nitrogen. Bacteria finely toothed edges that are lighter green since they are wind-pollinated and don’t in their root nodules move nitrogen from the underneath. -

Developing Species-Habitat Relationships: 2016 Project Report

Field Keys to Groups and Alliances in the National Vegetation Classification: Northern Basin & Range / Columbia Plateau Ecoregions NatureServe Conservation Science Division P r i n c i p a l Investigator Patrick J. C o m e r , Chief Ecologist [email protected] 703.797.4802 November 2017 Photos (clockwise from top left; all used under Creative Commons license CC BY 2.0.): Big sage shrubland, Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest, Nevada. USDA Photo by Susan Elliot. http://flic.kr/p/ax64DY Jeffrey pine woodland, photo by David Prasad. https://www.flickr.com/photos/33671002@N00 Northwest Great Plains Mixedgrass Prairie, Dakota Prairie National Grasslands, North Dakota. Western juniper woodland, BLM Black Hills Recreation Area, Oregon. Acknowledgements This work was completed with funding provided by the Bureau of Land Management through the BLM’s Fish, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Resource Management Program under Cooperative Agreement L13AC00286 between NatureServe and the BLM. Suggested citation: Schulz, K., G. Kittel, M. Reid and P. Comer. 2017. Field Keys to Divisions, Macrogroups, Groups and Alliances in the National Vegetation Classification: Northern Basin & Range / Columbia Plateau Ecoregions. Report prepared for the Bureau of Land Management by NatureServe, Arlington VA. 14p + 58p of Keys + Appendices. See appendix document: Descriptions_NVC_Groups_Alliances_ NorthernBasinRange_Nov_2017.pdf 2 | P a g e Contents Introduction and Background ...................................................................................................................... -

Salix Sessilifolia Nutt

Salix sessilifolia Nutt. soft-leaved willow Salicaceae - willow family status: State Sensitive, BLM sensitive, USFS sensitive rank: G4 / S2 General Description: Shrub or small tree 2-8 m tall, with a trunk up to 1 dm thick; leaves, young twigs, and capsules copiously covered with long, soft, loose, unmatted hairs, but less so with age. Stipules minute, deciduous; petioles 1-5 mm long. Leaf blades lance-shaped to oblong, (2.5) 3-7 (10) times as long as wide, the well-developed ones 3-10 x 1-3.5 cm; both sides are light green, densely hairy, soft and velvety to the touch, and have margins toothed with small, widely spaced teeth (sometimes entire). Winter buds covered with a single, nonresinous, caplike scale. Floral Characteristics: Male and female catkins borne on separate plants. C atkins develop on leafy branchlets after the leaves develop. Floral scales yellow to light yellowish green, hairy, and deciduous. Stamens 2; filaments conspicuously hairy below. Female catkins 3-5 (10) cm long; stigma lobes long and slender. Flowers May to June. Illustration by Jeanne R. Janish, ©1964 University of Washington Fruits: Capsules hairy, 3-5 mm long, occasionally 3-valved. Press Identif ication Tips: The young leaves and twigs of S. s es s ilifolia are copiously covered with soft, loose, unmatted hairs on both sides, and the leaves are 2.5-10 times as long as wide. In contrast, the young leaves and twigs of S. columbiana* are silvery from stiff, appressed hairs (rapidly becoming greener and nearly hairless), and the leaves are 5-15 (20) times as long as wide. -

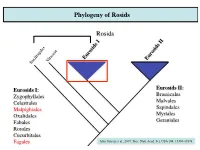

Phylogeny of Rosids! ! Rosids! !

Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Alnus - alders A. rubra A. rhombifolia A. incana ssp. tenuifolia Alnus - alders Nitrogen fixation - symbiotic with the nitrogen fixing bacteria Frankia Alnus rubra - red alder Alnus rhombifolia - white alder Alnus incana ssp. tenuifolia - thinleaf alder Corylus cornuta - beaked hazel Carpinus caroliniana - American hornbeam Ostrya virginiana - eastern hophornbeam Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Fagaceae (Beech or Oak family) ! Fagaceae - 9 genera/900 species.! Trees or shrubs, mostly northern hemisphere, temperate region ! Leaves simple, alternate; often lobed, entire or serrate, deciduous