Angeles National Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pinus Sabiniana) in Oregon Frank Callahan PO Box 5531, Central Point, OR 97502

Discovering Gray Pine (Pinus sabiniana) in Oregon Frank Callahan PO Box 5531, Central Point, OR 97502 “Th e tree is remarkable for its airy, widespread tropical appearance, which suggest a region of palms rather than cool pine woods. Th e sunbeams sift through even the leafi est trees with scarcely any interruption, and the weary, heated traveler fi nds little protection in their shade.” –John Muir (1894) ntil fairly recently, gray pine was believed to be restricted to UCalifornia, where John Muir encountered it. But the fi rst report of it in Oregon dates back to 1831, when David Douglas wrote to the Linnaean Society of his rediscovery of Pinus sabiniana in California. In his letter from San Juan Bautista, Douglas claimed to have collected this pine in 1826 in Oregon while looking for sugar pine (Pinus lambertiana) between the Columbia and Umpqua rivers (Griffin 1962). Unfortunately, Douglas lost most of his fi eld notes and specimens when his canoe overturned in the Santiam River (Harvey 1947). Lacking notes and specimens, he was reluctant to report his original discovery of the new pine in Oregon until he found it again in California (Griffin 1962). Despite the delay in reporting it, Douglas clearly indicated that he had seen this pine before he found it in California, and the Umpqua region has suitable habitat for gray pine. John Strong Newberry1 (1857), naturalist on the 1855 Pacifi c Railroad Survey, described an Oregon distribution for Pinus sabiniana: “It was found by our party in the valleys of the coast ranges as far north as Fort Lane in Oregon.” Fort Lane was on the eastern fl ank of Blackwell Hill (between Central Point and Gold Hill in Jackson County), so his description may also include the Th e lone gray pine at Tolo, near the old Fort Lane site, displays the characteristic architecture of multiple Applegate Valley. -

GRAY PINE Gray Squirrels

GRAY PINE gray squirrels. Mule and white-tailed deer browse Pinus sabiniana Dougl. ex the foliage and twigs. Dougl. Status plant symbol = PISA2 Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s Contributed By: USDA, NRCS, National Plant Data current status, such as, state noxious status, and Center wetland indicator values. Alternative Names Description General: Pine Family (Pinaceae). This native tree reaches 38 m in height with a trunk less than 2 m wide. The gray-green foliage is sparse and it has three needles per bundle. Each needle reaches 9-38 cm in length. The trunk often grows in a crooked fashion and is deeply grooved when mature. The seed cone of gray pine is pendent, 10-28 cm, and opens slowly during the second season, dispersing winged seeds. Distribution Charles Webber © California Academy of Sciences It ranges in parts of the California Floristic Province, @CalPhotos the western Great Basin and western deserts. For foothill pine, bull pine, digger pine, California current distribution, please consult the Plant Profile foothill pine page for this species on the PLANTS Web site. Uses Establishment Ethnobotanic: The seeds of gray pine were eaten by Adaptation: This tree is found in the foothill many California Indian tribes and are still served in woodland, northern oak woodland, chaparral, mixed Native American homes today. They can be eaten conifer forests and hardwood forests from 150- fresh and whole in the raw state, roasted, or pounded 1500m. into flour and mixed with other types of seeds. The seeds were eaten by the Pomo, Sierra Miwok, Extract seeds from the cones and gently rub the Western Mono, Wappo, Salinan, Southern Maidu, wings off, and soak them in water for 48 hours, drain Lassik, Costanoan, and Kato, among others. -

View Plant List Here

12th annual Theodore Payne Native Plant Garden Tour Plant List GARDEN 5 in pasadena provided by homeowner Botanical Name Common Name Abutilon palmeri Indian Mallow Achillea millefolium ‘Calistoga’ Calistoga Yarrow Achillea millefolium ‘Island Pink’ Island Pink Yarrow Achnatherum--see Stipa Aesculus californica California Buckeye Arctostaphylos glauca Big Berry Manzanita Arctostaphylos silvicola ‘Ghostly’ Ghostly Manzanita Artemisia californica California Sagebrush Artemisia ludoviciana ‘Silver King’ Silver King Wormwood Artemisia tridentata Great Basin Sagebrush Asclepias eriocarpa Kotolo or Indian Milkweed Astragalus pychnostachyus var. lanosissimus Ventura Marsh Milkvetch Bahiopsis (Viguiera) laciniata San Diego Sunflower Berberis (Mahonia) nervosa Cascades Oregon Grape Bergerocactus emoryi Cunyado, Golden Spined Cereus Brahea armata Mexican Blue Palm Calystegia macrostegia ‘Anacapa Pink’ Anacapa Pink Island Morning Glory Carpenteria californica Bush Anemone Dendromecon harfordii Channel Island Bush Poppy Diplacus (Mimulus) aurantiacus var. puniceus ‘Torrey Torrey Pines Red Bush Monkeyflower Pines’ Dudleya anomala no common name Dudleya pulverulenta Chalk Dudleya Encelia californica California Bush Sunflower Encelia farinosa Brittlebush, Incienso Epilobium (Zauschneria) ‘Silver Select’ Silver Select California Fuchsia Eriogonum fasciculatum ‘Dana Point’ Dana Point California Buckwheat Fouquieria splendens Ocotillo Frangula (Rhamnus) californica ‘Eve Case’ Eve Case Coffeeberry Gutierrezia californica California Matchweed Hazardia detonsa -

Fire Adaptations of Some Southern California Plants

Proceedings: 7th Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference 1967 Fire Adaptations of Some Southern California Plants RICHARD J. VOGL Department of Botany California State College at Los Angeles Los Angeles, California SHORTLY after arriving in California six years ago, I was asked to give a biology seminar lecture on my research. This was the usual procedure with new faculty and I prepared a lecture on my fire research in Wisconsin (Vogi 1961). These seminars were open to the public, since the college serves the city and sur rounding communities. As I presented my findings, I became con scious of the glint of state and U. S. Forest Service uniforms in the back rows. These back rows literally erupted into a barrage of probing questions at the end of the lecture. The questions were somewhat skeptical and were intended to discredit. They admitted that I almost created an acceptable argument for the uses and effects of fire in the Midwest, but were quick to emphasize that they were certain that none of these concepts or principles of fire would apply out here in the West. I consider this first California Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Con ference a major step towards convincing the West that fire has helped shape its vegetation and is an important ecological factor here, just as it is in the Midwest, Southeast, or wherever in North 79 RICHARD J. VOGL America. I hope that southern Californians attending these meetings or reading these Proceedings are not left with the impression that the information presented might be acceptable for northern California but cannot be applied to southern California because the majority of contributors worked in the north. -

CDFG Natural Communities List

Department of Fish and Game Biogeographic Data Branch The Vegetation Classification and Mapping Program List of California Terrestrial Natural Communities Recognized by The California Natural Diversity Database September 2003 Edition Introduction: This document supersedes all other lists of terrestrial natural communities developed by the Natural Diversity Database (CNDDB). It is based on the classification put forth in “A Manual of California Vegetation” (Sawyer and Keeler-Wolf 1995 and upcoming new edition). However, it is structured to be compatible with previous CNDDB lists (e.g., Holland 1986). For those familiar with the Holland numerical coding system you will see a general similarity in the upper levels of the hierarchy. You will also see a greater detail at the lower levels of the hierarchy. The numbering system has been modified to incorporate this richer detail. Decimal points have been added to separate major groupings and two additional digits have been added to encompass the finest hierarchal detail. One of the objectives of the Manual of California Vegetation (MCV) was to apply a uniform hierarchical structure to the State’s vegetation types. Quantifiable classification rules were established to define the major floristic groups, called alliances and associations in the National Vegetation Classification (Grossman et al. 1998). In this document, the alliance level is denoted in the center triplet of the coding system and the associations in the right hand pair of numbers to the left of the final decimal. The numbers of the alliance in the center triplet attempt to denote relationships in floristic similarity. For example, the Chamise-Eastwood Manzanita alliance (37.106.00) is more closely related to the Chamise- Cupleaf Ceanothus alliance (37.105.00) than it is to the Chaparral Whitethorn alliance (37.205.00). -

University of California Santa Cruz Responding to An

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ RESPONDING TO AN EMERGENT PLANT PEST-PATHOGEN COMPLEX ACROSS SOCIAL-ECOLOGICAL SCALES A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES with an emphasis in ECOLOGY AND EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY by Shannon Colleen Lynch December 2020 The Dissertation of Shannon Colleen Lynch is approved: Professor Gregory S. Gilbert, chair Professor Stacy M. Philpott Professor Andrew Szasz Professor Ingrid M. Parker Quentin Williams Acting Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Shannon Colleen Lynch 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables iv List of Figures vii Abstract x Dedication xiii Acknowledgements xiv Chapter 1 – Introduction 1 References 10 Chapter 2 – Host Evolutionary Relationships Explain 12 Tree Mortality Caused by a Generalist Pest– Pathogen Complex References 38 Chapter 3 – Microbiome Variation Across a 66 Phylogeographic Range of Tree Hosts Affected by an Emergent Pest–Pathogen Complex References 110 Chapter 4 – On Collaborative Governance: Building Consensus on 180 Priorities to Manage Invasive Species Through Collective Action References 243 iii LIST OF TABLES Chapter 2 Table I Insect vectors and corresponding fungal pathogens causing 47 Fusarium dieback on tree hosts in California, Israel, and South Africa. Table II Phylogenetic signal for each host type measured by D statistic. 48 Table SI Native range and infested distribution of tree and shrub FD- 49 ISHB host species. Chapter 3 Table I Study site attributes. 124 Table II Mean and median richness of microbiota in wood samples 128 collected from FD-ISHB host trees. Table III Fungal endophyte-Fusarium in vitro interaction outcomes. -

The Vascular Flora of the Upper Santa Ana River Watershed, San Bernardino Mountains, California

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281748553 THE VASCULAR FLORA OF THE UPPER SANTA ANA RIVER WATERSHED, SAN BERNARDINO MOUNTAINS, CALIFORNIA Article · January 2013 CITATIONS READS 0 28 6 authors, including: Naomi S. Fraga Thomas Stoughton Rancho Santa Ana B… Plymouth State Univ… 8 PUBLICATIONS 14 3 PUBLICATIONS 0 CITATIONS CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Available from: Thomas Stoughton Retrieved on: 24 November 2016 Crossosoma 37(1&2), 2011 9 THE VASCULAR FLORA OF THE UPPER SANTA ANA RIVER WATERSHED, SAN BERNARDINO MOUNTAINS, CALIFORNIA Naomi S. Fraga, LeRoy Gross, Duncan Bell, Orlando Mistretta, Justin Wood1, and Tommy Stoughton Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden 1500 North College Avenue Claremont, California 91711 1Aspen Environmental Group, 201 North First Avenue, Suite 102, Upland, California 91786 [email protected] All Photos by Naomi S. Fraga ABSTRACT: We present an annotated catalogue of the vascular flora of the upper Santa Ana River watershed, in the southern San Bernardino Mountains, in southern California. The catalogue is based on a floristic study, undertaken from 2008 to 2010. Approximately 65 team days were spent in the field and over 5,000 collections were made over the course of the study. The study area is ca. 155 km2 in area (40,000 ac) and ranges in elevation from 1402 m to 3033 m. The study area is botanically diverse with more than 750 taxa documented, including 56 taxa of conservation concern and 81 non-native taxa. Vegetation and habitat types in the area include chaparral, evergreen oak forest and woodland, riparian forest, coniferous forest, montane meadow, and pebble plain habitats. -

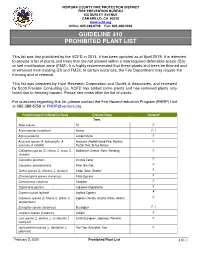

Guideline 410 Prohibited Plant List

VENTURA COUNTY FIRE PROTECTION DISTRICT FIRE PREVENTION BUREAU 165 DURLEY AVENUE CAMARILLO, CA 93010 www.vcfd.org Office: 805-389-9738 Fax: 805-388-4356 GUIDELINE 410 PROHIBITED PLANT LIST This list was first published by the VCFD in 2014. It has been updated as of April 2019. It is intended to provide a list of plants and trees that are not allowed within a new required defensible space (DS) or fuel modification zone (FMZ). It is highly recommended that these plants and trees be thinned and or removed from existing DS and FMZs. In certain instances, the Fire Department may require the thinning and or removal. This list was prepared by Hunt Research Corporation and Dudek & Associates, and reviewed by Scott Franklin Consulting Co, VCFD has added some plants and has removed plants only listed due to freezing hazard. Please see notes after the list of plants. For questions regarding this list, please contact the Fire Hazard reduction Program (FHRP) Unit at 085-389-9759 or [email protected] Prohibited plant list:Botanical Name Common Name Comment* Trees Abies species Fir F Acacia species (numerous) Acacia F, I Agonis juniperina Juniper Myrtle F Araucaria species (A. heterophylla, A. Araucaria (Norfolk Island Pine, Monkey F araucana, A. bidwillii) Puzzle Tree, Bunya Bunya) Callistemon species (C. citrinus, C. rosea, C. Bottlebrush (Lemon, Rose, Weeping) F viminalis) Calocedrus decurrens Incense Cedar F Casuarina cunninghamiana River She-Oak F Cedrus species (C. atlantica, C. deodara) Cedar (Atlas, Deodar) F Chamaecyparis species (numerous) False Cypress F Cinnamomum camphora Camphor F Cryptomeria japonica Japanese Cryptomeria F Cupressocyparis leylandii Leyland Cypress F Cupressus species (C. -

Alder Canopy Dieback and Damage in Western Oregon Riparian Ecosystems

Alder Canopy Dieback and Damage in Western Oregon Riparian Ecosystems Sims, L., Goheen, E., Kanaskie, A., & Hansen, E. (2015). Alder canopy dieback and damage in western Oregon riparian ecosystems. Northwest Science, 89(1), 34-46. doi:10.3955/046.089.0103 10.3955/046.089.0103 Northwest Scientific Association Version of Record http://cdss.library.oregonstate.edu/sa-termsofuse Laura Sims,1, 2 Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Oregon State University, 1085 Cordley Hall, Corvallis, Oregon 97331 Ellen Goheen, USDA Forest Service, J. Herbert Stone Nursery, Central Point, Oregon 97502 Alan Kanaskie, Oregon Department of Forestry, 2600 State Street, Salem, Oregon 97310 and Everett Hansen, Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, 1085 Cordley Hall, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97331 Alder Canopy Dieback and Damage in Western Oregon Riparian Ecosystems Abstract We gathered baseline data to assess alder tree damage in western Oregon riparian ecosystems. We sought to determine if Phytophthora-type cankers found in Europe or the pathogen Phytophthora alni subsp. alni, which represent a major threat to alder forests in the Pacific Northwest, were present in the study area. Damage was evaluated in 88 transects; information was recorded on damage type (pathogen, insect or wound) and damage location. We evaluated 1445 red alder (Alnus rubra), 682 white alder (Alnus rhombifolia) and 181 thinleaf alder (Alnus incana spp. tenuifolia) trees. We tested the correlation between canopy dieback and canker symptoms because canopy dieback is an important symptom of Phytophthora disease of alder in Europe. We calculated the odds that alder canopy dieback was associated with Phytophthora-type cankers or other biotic cankers. -

Adenostoma Sparsifolium Torr. (Rosaceae), Arctostaphylos Peninsularis Wells (Ericaceae), Artemisia Tridentata Nutt

66 JOURNAL OF THE LEPIDOPTERISTS' SOCIETY Ceanothus greggii A. Gray (Rhamnaceae), Adenostoma sparsifolium Torr. (Rosaceae), Arctostaphylos peninsularis Wells (Ericaceae), Artemisia tridentata Nutt. (Asteraceae), Quercus chrysolepis Liebm. and Q. dumosa Nutt. (Fagaceae), and Pinus jefferyi Grev. & BaH. (Pinaceae). On 27 and 29 October 1989 the unmated females were caged at a site in the vicinity of Mike's Sky Ranch in the Sierra San Pedro Martir, approximately 170 km south of the international border. Despite sunny weather and at a similar elevation and floral com munity, no males were attracted. Two males were deposited as voucher specimens in both of the following institutions: Universidad Autonoma de Baja California Norte, Ensenada, Mexico, and the Essig Mu seum of Entomology, University of California, Berkeley. Eleven specimens are in the private collection of John Noble, Anaheim Hills, California; the remaining 22 specimens are in the collection of the author. RALPH E. WELLS, 303-8 Hoffman Street, Jackson, California 95642. Received for publication 10 February 1990; revised and accepted 15 March 1991. Journal of the Lepidopterists' SOCiety 45(1), 1991, 66-67 POSITIVE RELATION BETWEEN BODY SIZE AND ALTITUDE OF CAPTURE SITE IN TORTRICID MOTHS (TORTRICIDAE) Additional key words: North America, biometrics, ecology. Earlier I reported a positive correlation between forewing length and altitude of capture site in the Nearctic tortricid Eucosma agricolana (Walsingham) (Miller, W. E. 1974, Ann. Entomol. Soc. Amer. 67:601-604). The all-male sample was transcontinental, with site altitudes ranging from near sea level on east and west coasts to more than 2700 m in the Rocky Mountains. Altitudes of capture came from labels of some specimens, and from topographic maps for others. -

RED ALDER Northwest Extracted a Red Dye from the Inner Bark, Which Was Used to Dye Fishnets

Plant Guide and hair. The native Americans of the Pacific RED ALDER Northwest extracted a red dye from the inner bark, which was used to dye fishnets. Oregon tribes used Alnus rubra Bong. the innerbark to make a reddish-brown dye for basket Plant Symbol = ALRU2 decorations (Murphey 1959). Yellow dye made from red alder catkins was used to color quills. Contributed by: USDA NRCS National Plant Data Center A mixture of red alder sap and charcoal was used by the Cree and Woodland tribes for sealing seams in canoes and as a softener for bending boards for toboggans (Moerman 1998). Wood and fiber: Red alder wood is used in the production of wooden products such as food dishes, furniture, sashes, doors, millwork, cabinets, paneling and brush handles. It is also used in fiber-based products such as tissue and writing paper. In Washington and Oregon, it was largely used for smoking salmon. The Indians of Alaska used the hallowed trunks for canoes (Sargent 1933). Medicinal: The North American Indians used the bark to treat many complaints such a headaches, rheumatic pains, internal injuries, and diarrhea (Moerman 1998). The Salinan used an extract of the bark of alder trees to treat cholera, stomach cramps, and stomachaches (Heinsen 1972). The extract was made with 20 parts water to 1 part fresh or aged bark. The bark contains salicin, a chemical similar to aspirin (Uchytil 1989). Infusions made from the bark of red alders were taken to treat anemia, colds, congestion, and to © Tony Morosco relieve pain. Bark infusions were taken as a laxative @ CalFlora and to regulate menstruation. -

Adenostoma Fasciculatum Profile to Postv2.Xlsx

I. SPECIES Adenostoma fasciculatum Hooker & Arnott NRCS CODE: ADFA Family: Rosaceae A. f. var. obtusifolium, Ron A. f. var. fasciculatum., Riverside Co., A. Montalvo, RCRCD Vanderhoff (Creative Order: Rosales Commons CC) Subclass: Rosidae Class: Magnoliopsida A. Subspecific taxa 1. Adenostoma fasciculatum var. fasciculatum Hook. & Arn. 1. ADFAF 2. A. f. var. obusifolium S. Watson 2. ADFAO 3. A. f. var. prostratum Dunkle 3. (no NRCS code) B. Synonyms 1. A. f. var. densifolium Eastw. 2. A. brevifolium Nutt. 3. none. Formerly included as part of A. f. var. f. C. Common name 1. chamise, common chamise, California greasewood, greasewood, chamiso (Painter 2016) 2. San Diego chamise (Calflora 2016) 3. prostrate chamise (Calflora 2016) Phylogenetic studies using molecular sequence data placedAdenostoma closest to Chamaebatiaria and D. Taxonomic relationships Sorbaria (Morgan et al. 1994, Potter et al. 2007) and suggest tentative placement in subfamily Spiraeoideae, tribe Sorbarieae (Potter et al. 2007). E. Related taxa in region Adenostoma sparsifolium Torrey, known as ribbon-wood or red-shanks is the only other species of Adenostoma in California. It is a much taller, erect to spreading shrub of chaparral vegetation, often 2–6 m tall and has a more restricted distribution than A. fasciculatum. It occurs from San Luis Obispo Co. south into Baja California. Red-shanks produces longer, linear leaves on slender long shoots rather than having leaves clustered on short shoots (lacks "fascicled" leaves). Its bark is cinnamon-colored and in papery layers that sheds in long ribbons. F. Taxonomic issues The Jepson eFlora and the FNA recognize A. f. var. prostratum but the taxon is not recognized by USDA PLANTS (2016).