Stream & Wetland Enhancement Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Note 37: Identification, Ecology, Use, and Culture of Sitka

TECHNICAL NOTES _____________________________________________________________________________________________ US DEPT. OF AGRICULTURE NATURAL RESOURCES CONSERVATION SERVICE Portland, OR April 2005 PLANT MATERIALS No. 37 Identification, Ecology, Use and Culture of Sitka Alder Dale C. Darris, Conservation Agronomist, Corvallis Plant Materials Center Introduction Sitka alder [Alnus viridis (Vill.) Lam. & DC. subsp. sinuata (Regel) A.& D. Löve] is a native deciduous shrub or small tree that grows to height of 20 ft, occasionally taller. Although a non-crop species, it has several characteristics useful for reclamation, forestry, and erosion control. The species is known for abundant leaf litter production, the fixation of atmospheric nitrogen in association with Frankia bacteria, and a strong fibrous root system. Where locally abundant, it naturally colonizes landslide chutes, areas of stream scour and deposition, soil slumps, and other drastic disturbances resulting in exposed minerals soils. These characteristics make Sitka alder particularly useful for streambank stabilization and soil building on impoverished sites. In addition, its low height and early slowdown in growth rate makes it potentially more desirable than red alder (Alnus rubra) to interplant with conifers such as Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menzieii) and lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta) where soil fertility is moderate to low. However, high densities can hinder forest regeneration efforts. The species may also be useful as a fast growing shrub row in field windbreaks. Sitka alder is most abundant at mid to subalpine elevations. Low elevation seed sources (below 100 m) are uncommon but probably provide the best material for reclamation and erosion control projects on valley floors and terraces. Distribution and Identification Sitka alder (Alnus viridis subsp. sinuata) is a native deciduous shrub or small tree that grows to a height of 1-6 m (3-19 ft) in the mountains and 6-12 m (19-37ft) at low elevations. -

TREES HAVE HIGHER LONGITUDINAL GROWTH STRAINS in THEIR STEMS THAN in THEIR ROOTS in the Secondary Xylem of Trees, Each Wood Cell

a3q14 Int. 1. Plant Sci. 158(4):418-423. 1997. © 1997 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. 1058-5893/97/5804-0003$03.00 TREES HAVE HIGHER LONGITUDINAL GROWTH STRAINS IN THEIR STEMS THAN IN THEIR ROOTS BARBARA L. GARTNER Department of Forest Products, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97 33 1-7402 Longitudinal growth strains develop in woody tissues during cell-wall formation. This study compares stems, which have a mechanical role and experience longitudinal stresses, and nonstructural roots, which have little mechanical role and experience few or no longitudinal stresses, to test the hypothesis that growth strains are produced in stems of straight trees as an adaptive feature for mechanical loads. I measured growth strains in one stem (at breast height) and one nonstructural root (beyond the zone of rapid taper and/or beyond a major change in root direction) for 13-15 individuals of each of four tree species, Pseudotsuga menziesii, Thuja heterophylla, Acer macrophyllum, and Alnus rubra. Forty-seven of the 54 individuals had higher strains in their stems than in their roots (4.3 ± 0.3 x 10- 4 and 1.5 ± 0.3 x 10-4, respectively). Growth strain was two to five times higher for stems than roots. The modulus of elasticity (MOE) in bending was also higher in stem tissues (from literature values) than in root tissue (from this study). Calculated growth stresses, the product of growth strain and MOE, averaged 6-11 times higher in stems than roots for the four species. The higher strain and stress in stems than roots indicate that the strains and stresses are adaptive features that are produced in response to, or in "anticipation," of mechanical loads. -

Nitrogen Transformations in Soils Beneath Red Alder and Conifers

From Biology of Alder ERTY OF: Proceedings of Northwest Scientific Association Annual Mee t4■::::),...;ADE HEAD EXPERIMENTAL FOREST April 14-15, 1967 Published 1968 AND SCENIC RESEARCH AREA OTIS, OREGON Nitrogen transformations in soils beneath red alder and conifers W. B. Bollen, Abstract Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon Transformations of nitrogen in organic matter in the soil are essential to and plant nutrition because nitrogen in the form of proteins and other organic K. C. Lu compounds is not directly available. These compounds must undergo Forestry Sciences Laboratory microbial decomposition to liberate nitrogen as ammonium (NH -I-4) and Pacific Northwest Forest nitrate (NO3 ), which can then be absorbed by plant roots. and Range Experiment Station Nitrogen transformations, particularly nitrification, are rapid in soils under Corvallis, Oregon coastal Oregon stands of red alder (Alnus rubra Bong.); conifers — Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco), western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla Raf) Sarg.), and Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis (Bong.) Carr.); and mixed stands of alder and conifers. Nitrification is especially rapid in the F layer beneath alder stands despite a very low pH. These findings are from a study of contributions to the nitrogen economy by red alder conducted at Cascade Head Experimental Forest near Otis, Oregon (Chen, 1965). 1 Procedures Ammonifying capacity of the different samples was compared by testing duplicate 50-g portions, ovendry basis, of each with peptone equivalent to 1,000 ppm nitrogen. These samples, and samples of untreated soil, were incubated for 35 days at 28 C. Moisture was adjusted to 50 percent of the water- holding capacity. At the close of incubation, each sample was analyzed for NH+4, NO-2, and NO-3 nitrogen and for pH. -

Alder Canopy Dieback and Damage in Western Oregon Riparian Ecosystems

Alder Canopy Dieback and Damage in Western Oregon Riparian Ecosystems Sims, L., Goheen, E., Kanaskie, A., & Hansen, E. (2015). Alder canopy dieback and damage in western Oregon riparian ecosystems. Northwest Science, 89(1), 34-46. doi:10.3955/046.089.0103 10.3955/046.089.0103 Northwest Scientific Association Version of Record http://cdss.library.oregonstate.edu/sa-termsofuse Laura Sims,1, 2 Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Oregon State University, 1085 Cordley Hall, Corvallis, Oregon 97331 Ellen Goheen, USDA Forest Service, J. Herbert Stone Nursery, Central Point, Oregon 97502 Alan Kanaskie, Oregon Department of Forestry, 2600 State Street, Salem, Oregon 97310 and Everett Hansen, Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, 1085 Cordley Hall, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97331 Alder Canopy Dieback and Damage in Western Oregon Riparian Ecosystems Abstract We gathered baseline data to assess alder tree damage in western Oregon riparian ecosystems. We sought to determine if Phytophthora-type cankers found in Europe or the pathogen Phytophthora alni subsp. alni, which represent a major threat to alder forests in the Pacific Northwest, were present in the study area. Damage was evaluated in 88 transects; information was recorded on damage type (pathogen, insect or wound) and damage location. We evaluated 1445 red alder (Alnus rubra), 682 white alder (Alnus rhombifolia) and 181 thinleaf alder (Alnus incana spp. tenuifolia) trees. We tested the correlation between canopy dieback and canker symptoms because canopy dieback is an important symptom of Phytophthora disease of alder in Europe. We calculated the odds that alder canopy dieback was associated with Phytophthora-type cankers or other biotic cankers. -

RED ALDER Northwest Extracted a Red Dye from the Inner Bark, Which Was Used to Dye Fishnets

Plant Guide and hair. The native Americans of the Pacific RED ALDER Northwest extracted a red dye from the inner bark, which was used to dye fishnets. Oregon tribes used Alnus rubra Bong. the innerbark to make a reddish-brown dye for basket Plant Symbol = ALRU2 decorations (Murphey 1959). Yellow dye made from red alder catkins was used to color quills. Contributed by: USDA NRCS National Plant Data Center A mixture of red alder sap and charcoal was used by the Cree and Woodland tribes for sealing seams in canoes and as a softener for bending boards for toboggans (Moerman 1998). Wood and fiber: Red alder wood is used in the production of wooden products such as food dishes, furniture, sashes, doors, millwork, cabinets, paneling and brush handles. It is also used in fiber-based products such as tissue and writing paper. In Washington and Oregon, it was largely used for smoking salmon. The Indians of Alaska used the hallowed trunks for canoes (Sargent 1933). Medicinal: The North American Indians used the bark to treat many complaints such a headaches, rheumatic pains, internal injuries, and diarrhea (Moerman 1998). The Salinan used an extract of the bark of alder trees to treat cholera, stomach cramps, and stomachaches (Heinsen 1972). The extract was made with 20 parts water to 1 part fresh or aged bark. The bark contains salicin, a chemical similar to aspirin (Uchytil 1989). Infusions made from the bark of red alders were taken to treat anemia, colds, congestion, and to © Tony Morosco relieve pain. Bark infusions were taken as a laxative @ CalFlora and to regulate menstruation. -

Brotherella Roellii (Renauld & Cardot) M

Brotherella roellii (Renauld & Cardot) M. Fleisch. Roll's golden log moss Sematophyllaceae status: State Threatened, USFS strategic rank: G3 / SH General Description: Shiny golden to yellowish green moss forming thin, small carpets. Stems lying flat, creeping, branching irregularly, 0.5-3 cm x 0.5-1 mm. Leaves 0.8-1.2 mm long, often turned to one side, ovate-lanceolate, tip pointed, concave. Costa lacking, or double and very short. Alar cells strongly inflated. Outer layer of stem cells (cortical cells) are inflated, colorless, transparent, and larger than the interior cells. There is often a row of enlarged cells extending across the leaf base. Reproductive Characteristics: Produces male and female sex organs on the same plant but in separate locations. Seta 0.6-1 cm long. Capsule erect to somewhat inclined, straight or slightly asymmetric. Urn 1-1.5 mm long. Operculum long and narrow, up to 1 mm long. Identification Tips: Hypnum circinale is a similar species that often grows in the same habitat. However, it is a larger moss, dull grayish to bluish green in color, with longer leaves (up to 2.2 mm) that are slightly to strongly curved nearly into a circle. It has only a few slightly inflated quadrate to rectangular, alar cells; its cortical cells are small and thick-walled. In contrast, B. roellii has strongly inflated alar cells, and large, thin-walled, inflated cortical cells. Range: Endemic to southwestern B.C. and WA. Habitat/Ecology: Forms small, glossy, green to golden yellow mats, usually on old logs and other rotten wood; also © Judy Harpel on the bases of red alder (Alnus rubra) and other hardwood trees. -

Salix Sessilifolia Nutt

Salix sessilifolia Nutt. soft-leaved willow Salicaceae - willow family status: State Sensitive, BLM sensitive, USFS sensitive rank: G4 / S2 General Description: Shrub or small tree 2-8 m tall, with a trunk up to 1 dm thick; leaves, young twigs, and capsules copiously covered with long, soft, loose, unmatted hairs, but less so with age. Stipules minute, deciduous; petioles 1-5 mm long. Leaf blades lance-shaped to oblong, (2.5) 3-7 (10) times as long as wide, the well-developed ones 3-10 x 1-3.5 cm; both sides are light green, densely hairy, soft and velvety to the touch, and have margins toothed with small, widely spaced teeth (sometimes entire). Winter buds covered with a single, nonresinous, caplike scale. Floral Characteristics: Male and female catkins borne on separate plants. C atkins develop on leafy branchlets after the leaves develop. Floral scales yellow to light yellowish green, hairy, and deciduous. Stamens 2; filaments conspicuously hairy below. Female catkins 3-5 (10) cm long; stigma lobes long and slender. Flowers May to June. Illustration by Jeanne R. Janish, ©1964 University of Washington Fruits: Capsules hairy, 3-5 mm long, occasionally 3-valved. Press Identif ication Tips: The young leaves and twigs of S. s es s ilifolia are copiously covered with soft, loose, unmatted hairs on both sides, and the leaves are 2.5-10 times as long as wide. In contrast, the young leaves and twigs of S. columbiana* are silvery from stiff, appressed hairs (rapidly becoming greener and nearly hairless), and the leaves are 5-15 (20) times as long as wide. -

Native Plants and Trees of Oregon

NATIVE PLANTS AND TREES OF OREGON LOW-MAINTENANCE NATIVE PLANTS TO CONSERVE WATER, HELP POLLINATORS NATIVE PLANTS AND TREES: Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) The Oregon white oak is an attractive deciduous hardwood VITAL TO HEALTHY ECOSYSTEMS tree found as far north as British Columbia and as far south as As open space and wildlife habitat diminish in urbanized southern California. The bark is grayish with shallow ridges and environments across the country, bee and pollinator fissures, leaves are dark green with 3-7 deep lobes on each side populations are down as well. What can we do so that our and acorns are about one inch long, with shallow, scaly cups. parks, neighborhoods and backyards can be healthier, better Urban development continually encroaches on the habitat of functioning ecosystems? this native tree. Unfortunately, because of its reputation as a slow Whether you’re a landowner, gardener, or manager of parks and grower, homeowners don’t often plant Oregon white oak. That’s a open spaces, there are some easy actions you can take to help shame, since they have much to offer, giving us welcome shade in bees and other pollinators. Consider the many benefits of using the summer and supplying habitat to important bird and wildlife native plants and trees to boost the ecosystem services of your including nuthatches, goldfinches and western gray squirrel. neighborhood and community. Mature oaks need sun, but can grow up to 75 feet tall so be sure In addition to being helpful for the environment, native to plant them only in yards or landscapes with ample room to plants are often low maintenance, attract pollinators including accommodate size. -

Distribution and Habitat Associations of the Northern Pygmy-Owl in Oregon

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Dawn M. Sater for the degree of Master of Science in Wildlife Science presentedon May 21. 1999. Title: Distribution and Habitat Associations of the Northern Pygmy-owl in Oregon. Redacted for Privacy Abstract approved: Eric D. Forsman I conducted acoustic lure surveys of northern pygmy-owls (Glaucidium gnoma)on transects that were systematically placed in forested areas throughout the state of Oregon. My objectives were to determine if pygmy-owlswere associated with particular forest types, ecoregions, or with large-diameter dominant overstory trees. I also examined temporal variation in response rates. All analyses accounted for decreases incounts of owls with increasing day of the surveyseason (P = 0.01) and with increasing time after sunrise (P = 0.06).Counts were highest in Douglas-fir, ponderosa pine and mixed conifer-hardwood forests, intermediate in mixed conifer, deciduousand high elevation forests, and lowest in western juniper (P= 0.0003). Even after accounting for forest type, numbers of owls detected variedamong ecoregions (P = 0.002). Counts of owls increased with the average diameter ranking ofdominant overstory trees (P = 0.000 1). Also, diameters of dominant treeswere greater at survey points where owls were detected than at survey points whereno owls were detected P = 0.008), and greater in the actual stands from which owls responded than around thesurvey points from which owls were detected (P = 0.0001). My data suggest that widespread decreases in large-diameter trees, or the late-successional forests in which such trees are most abundant, may reduce numbers of northern pygmy-owls. However, this finding needs to be viewed in the context that my surveys also show that the pygmy-owl is a well-distributed and fairly common forest bird in Oregon and is not limited to late-successional forest. -

Burning Characteristics of Big Leaf Maple, Red Alder, and Black Cottonwood Leaves

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Honors Program Senior Projects WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Fall 2000 Burning Characteristics of Big Leaf Maple, Red Alder, and Black Cottonwood Leaves Elizabeth Ralston Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Ralston, Elizabeth, "Burning Characteristics of Big Leaf Maple, Red Alder, and Black Cottonwood Leaves" (2000). WWU Honors Program Senior Projects. 264. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors/264 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Honors Program Senior Projects by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WESTERN WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY An equal opportunity university Honors Program Bellingham, Washington 98225-9089 (360)650-3034 Fax (360) 650-7305 HONORS THESIS In presenting this Honors paper in partial requirements fora bachelor’s degree at Western Washington University, I agree that the Library shall make its copies freely available for inspection. I further agree that extensive copying of this thesis is allowable only for scholarly purposes. It is understood that any publication of this thesis for commercial purposes or for financial gain shall not be allowed without mv written permission. Signatur Date12.^ 2/10(0 Burning characteristics of big leaf maple, red alder, and black cottonwood leaves Elizabeth Ralston Biology Department, Western Washington University, Bellingham, Washington Senior Honors Project December 12, 2000 Abstract The leaves from three Northwest deciduous trees were burned to compare flammability of nonwoody fuels. -

TREEID Bartlett Tree ID (If APL) Species Common DBH Height Conditiontype Dmaintenance 310-97007 289 Acer Macrophyllum Bigleaf Ma

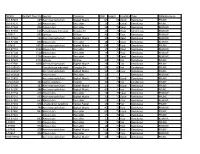

TREEID Bartlett Tree ID (IfSpecies APL) Common DBH Height ConditionType DMaintenance 310-97007 289 Acer macrophyllum Bigleaf Maple 67 50 Good Deciduous PRUNE 310-97076 358 Alnus rubra Red alder 16 75 Good Deciduous PRUNE 310-97124 406 Alnus rubra Red alder 18 75 Dead Deciduous REMOVE 310-97234 616 Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas Fir 16 75 Dead Coniferous REMOVE 0-97311 693 Salix sp Willow 40 75 Poor Deciduous REMOVE 310-97369 751 Acer macrophyllum Bigleaf Maple 22 75 Dead Deciduous REMOVE 310-97508 890 Alnus rubra Red alder 18 75 Dead Deciduous REMOVE 0-97619 1401 Acer macrophyllum Bigleaf Maple 64 75 Poor Deciduous PRUNE 310-97741 1523 Alnus rubra Red alder 17 25 Dead Deciduous REMOVE 310-97748 1530 Alnus rubra Red alder 29 75 Poor Deciduous REMOVE 310-97856 1704 Alnus rubra Red alder 27 75 Dead Deciduous REMOVE 310-97923 1771 Salix sp Willow 20 75 Fair Deciduous PRUNE 310-97980 1828 Acer macrophyllum Bigleaf Maple 28 75 Fair Deciduous PRUNE 310-158160 Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas Fir 44 80 Fair Coniferous PRUNE 310-162010 Acer macrophyllum Bigleaf Maple 32 40 Poor Deciduous PRUNE 310-162644 Alnus rubra Red alder 12 Deciduous REMOVE 310-22801 Acer macrophyllum Bigleaf Maple 56 55 Good Deciduous PRUNE 4470-97061 343 Cedrus deodara Deodar 36 75 Fair Coniferous PRUNE 310-97100 382 Acer macrophyllum Bigleaf Maple 11 75 Good Deciduous PRUNE 310-97106 388 Acer macrophyllum Bigleaf Maple 45 75 Fair Deciduous PRUNE 310-97134 416 Alnus rubra Red alder 24 75 Dead Deciduous REMOVE 310-97141 423 Acer macrophyllum Bigleaf Maple 21 75 Good Deciduous -

VINE MAPLE Above and Paler Beneath

KNOW YOUR SPECIES palmately veined with 5 to 1 1 lobes, dark green VINE MAPLE above and paler beneath. The petioles are 1 to 2 inches long and grooved. In the fall the leaves (Acer circinatum) become a rich scarlet. The flowers are reddish- purple, occurring in umbel-like clusters of 2 to 10 or more. The twigs are purple. This plant grows along stream banks and in well-drained shaded areas from the coastal mountains of British Columbia southward to north- ern California. It commonly forms an understory in pine, fir and coast hemlock forests from near sea level to an elevation of 5000 feet. Associated with vine maple is bigleaf maple (A. macrophyl- lum), red alder (Alnus rubra), and other woody species. Neither vine maple nor the other species may be any real economic problem in old virgin forests, but all of them may interfere in reforest- ation following either logging or forest fire. Vine maple, a vigorous sprouter, may not be a problem to, for example, Douglas-fir seedlings that require shade when young; but it may slow the growth of well-established trees, making them spindly and weak unless the competition for light and moisture is removed. Diameter growth improves when such competition is eliminated, but the in- crease in growth may require about 3 years to become significant. In the Douglas-fir region of western Washington and Oregon, there are two general types of aerial sprays for release of existing conifers or prepara- tion of areas for stocking by artificial means: bud- break spray (when buds are swelling) and foliage Drawing from: California Range Brushlands and Browse Plants, spray.