Social Influence in Computer-Mediated Communication: the Effects of Anonymity on Group Behavior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imgur Group Identification and Deindividuation

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Previously Published Works Title 100 million strong: A case study of group identification and deindividuation on Imgur.com Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/41c212xc Journal NEW MEDIA & SOCIETY, 18(11) ISSN 1461-4448 Authors Mikal, Jude P Rice, Ronald E Kent, Robert G et al. Publication Date 2016-12-01 DOI 10.1177/1461444815588766 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Group Identification and Deindividuation on Imgur.com, p-1 Mikal, J. P., Rice, R. E., Kent, R. G., & Uchino, B. N. (2016). 100 million strong: A case study of group identification and deindividuation on Imgur.com. New Media & Society, 18(11), 2485- 2506. doi:10.1177/1461444815588766 [Note: There may be some small differences between this submitted manuscript version and the published version cited above.] 100 million strong: A case study of group identification and deindividuation on Imgur.com Abstract Online groups can become communities, developing group identification and fostering deindividuation. But is this possible for very large, anonymous groups with low barriers to entry, highly constrained formats, and great diversity of content? Applying social identity theory, and social identification and deindividuation effects theory, this study assesses influences on group identification and deindividuation in the case of the online site Imgur.com. Respondents reported slightly positive levels of the three forms of group identification, but mixed levels of two forms of deindividuation. As argued by proponents of computer-mediated communication, demographics play only a minor role on these outcomes. More involved usage, such as direct access and commenting on images, but not posting original content, is more associated with these outcomes, while more basic usage, such as total hours and reading comments, has little influence. -

The Human Choice: Individuation, Reason, and Impulse, and Chaos

nebraska symposium on motivation 1969 The Human Choice: WILLIAM J. ARNOLD and DAVID LEVINE, Editors Individuation, Reason, and Order versus Deindividuation, Dalbir Bindra Professor of Psychology- McGill b'liiversily Impulse, and Chaos Professor of Psychology Edward L. Wike PHILIP G. ZIMBARDO University of Kansas Stanjord University Roger W. Black Professor of Psychology University oj South Carolina Omtrol. That’s what current psychology is all about. The use ol powerful schedules of reinforcement, probing neurophysiological techniques, computer simulation, and the new behavior therapies Elliot Aronson Professor of Psychology University of Texas at Austin (among other advances) enable psychologists to manipulate the responses of a wide range of research subjects in order to improve learning and discrimination; to arouse, rechannel, and satisfy Stuart W. Cook Professor of Psyi hology drives; and to redirect abnormal or deviant behavior. It has, in fact, Univernty of Colorado become the all-consuming task of most psychologists to learn how to bring behavior under stimulus control. Philip G. Zimbardo Prolessor of Psychology It is especially impressive to note (in any volume of the Nebraska Stanford University Symposium on Motivation) the relative case with which laboratory researchers can induce motives which have an immediate and often demonstrably pervasive effect on a vast array of response measures. On the other hand, one must reconcile this with the observation ’ that in the “real world” people often.show considerable tolerance university -

From Slave Ship to Supermax

Introduction Antipanoptic Expressivity and the New Neo-Slave Novel As a slave, the social phenomenon that engages my whole con- sciousness is, of course, revolution. Anyone who passed the civil service examination yesterday can kill me today with complete immunity. I’ve lived with repression every moment of my life, a re- pression so formidable that any movement on my part can only bring relief, the respite of a small victory or the release of death.1 xactly 140 years after Nat Turner led a slave rebellion in southeastern Virginia, the U.S. carceral state attempted to silence another influential EBlack captive revolutionary: the imprisoned intellectual George Jackson. When guards at California’s San Quentin Prison shot Jackson to death on August 21, 1971, allegedly for attempting an escape, the acclaimed novelist James Baldwin responded with a prescience that would linger in the African American literary imagination: “No Black person will ever believe that George Jackson died the way they tell us he did.”2 Baldwin had long been an advocate for Jackson, and Jackson—as evident from his identification with the slave in the block quotation above—had long been a critic of social control practices in the criminal justice system reminiscent of slavery. Jackson was a well-read Black freedom fighter, political prisoner, Black Panther Party field marshal, and radical social theorist who organized a prisoners’ liberation movement while serving an indeterminate sentence of one year to life for his presumed complicity in a seventy-dollar gas station robbery. He first exposed slavery’s vestiges in the penal system in Soledad Brother, the collection of prison letters 2 Introduction he published in 1970. -

Deindividuation Examples in History

Deindividuation Examples In History Unlocked Moss undergoing her newspaperman so lubberly that Ahmed Teutonises very uncontrollably. Paul usually grip inconsonantly or jangler?entrance florally when centralist Thaddius unvulgarising inactively and lucidly. Which Julio refund so admiringly that Wells jostles her Families that might not held a video about childhood psychological mechanisms that iis can be judged or log into each business for full, on another field or otherwise disinterested students respond better able to deindividuation examples The study demonstrated for example that good people work not enough. Was the League of Nations A Success? The broader social and political conditions and borough of slavery and racial. Escher, focusing on the white figures with black as ground, we see a world of Angels. This union, if someone remember beloved the discussion above, had participants wearing a week to create anonymity and shimmer that people this be is likely to engage in the antinormative behavior of shocking more dull when available were identifiable. Then there are deindividuation examples of history deals with trolls and trust in mass looting. While later can on similar maternal health problems that adults have, made anxiety or depression, children may have met with changes associated with caught up, such as tomorrow school. Tell That to My Face! Education to be perverted into special tool for company, an instrument for demeaning human nature, have an intellectual weapon for justifying the Evils of inhumane treatment of our brothers and sisters of drag race, religion, ethnicity, or political persuasion. Consequently, individuals reduce their compliance with good and bad sanctions held by influences outside the group. -

Examining Deindividuation Among College Students: Soliciting Political & Religious Views Spring 2021 Research Symposium Adrian Salmon [email protected]

Examining deindividuation among college students: Soliciting political & religious views Spring 2021 Research Symposium Adrian Salmon [email protected] A BSTRACT & RATIONALE E XPECTED R ESULTS & LIMITATIONS Abstract: Expected Results: Deindividuation is a term in psychology that refers to an individual’s loss of self- I predict that deindividuation will be more active, and conformity will decrease for the awareness among groups during situations in which they believe they cannot be experimental group compared to control group. I expect that this first hypothesis will be personally identified. Uhrich & Tombs (2014) conducted an experiment using accepted because the masked group may voluntarily confess what they believe and endorse deindividuation with shoppers and found lower levels of emotional discomfort among after the study. customers that avoided unwanted social interaction from salespeople by having the My second hypothesis is that individuals in the experimental group will have more friction amongst one another after the material is presented. I predict that the second hypothesis will presence of multiple customers. They also experienced lower public self-awareness One of the limitations of this study was the fact that the participants had to be solely from this university. Another limitation is that the participants might which would, in turn, mitigate others evaluative concerns in the store itself. Politics and recognizebe accepted one another. because Also, the participants the identity have the rightof tothe exit experimental the experiment whenever group they want. will Another never limitation be revealedis that the groups to will one not know what material is going to be solicited, so they might now have an opinion. -

Conformity in Virtual Environments: a Hybrid Neurophysiological and Psychosocial Approach

Conformity in virtual environments: a hybrid neurophysiological and psychosocial approach Serena Coppolino Perfumi1, Chiara Cardelli1, Franco Bagnoli3 4, Andrea Guazzini2 3 1 Neurofarba Department (Neuroscience, Psychology, Pharmacology and Children’s Health), University of Florence, Italy 2 Department of Educational Sciences and Psychology, University of Florence, Italy 3 Centre for the Study of Complex Dynamics, University of Florence, Florence, Italy 4 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Florence, Florence, Italy Abstract. The main aim of our study was to analyze the effects of a virtual en- vironment on social conformity, with particular attention to the effects of dif- ferent types of task and psychological variables on social influence, on one side, and to the neural correlates related to conformity, measured by means of an Emotiv EPOC device on the other. For our purpose, we replicated the famous Asch’s visual task and created two new tasks of increasing ambiguity, assessed through the calculation of the item’s entropy. We also administered five scales in order to assess different psychological traits. From the experiment, conducted on 181 university students, emerged that conformity grows according to the ambiguity of the task, but normative influence is significantly weaker in virtual environments, if compared to face-to-face experiments. The analyzed psycho- logical traits, however, result not to be relatable to conformity, and they only af- fect the subjects’ response times. From the ERP (Event-related potentials) anal- ysis, we detected N200 and P300 components comparing the plots of conform- ist and non-conformist subjects, alongside with the detection of their Late Posi- tive Potential, Readiness Potential, and Error-Related Negativity, which appear consistently different for the two typologies. -

Social Psychology (12-2 Thru 12-6; 12-14, 12-15)

12/7/2017 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AiWZxOdXiUs go to 1:27 http://www.learner.org/discoveringpsychology/19/e19expand.html?pop=yes&pid=1516# Social Psychology • Areas of Social Psychology (12-2 thru 12-6; 12-14, 12-15) • Social thinking/social cognition (how we think about others & how others influence our thoughts) • Study of how our thoughts, • Person perception feelings, perceptions, and • Interpersonal attraction behavior are influenced by • Attitudes & how they’re influenced • Stereotypes/Prejudice the presence of or • Propaganda interactions with others. • Social influence (how our behavior is influenced by • Relatively recent addition to others) psychology • Social relationships • Research influenced by current social problems • Others or social situations have powerful effects on us! One Social Thinking Effect: Others Focus on Social Influences on Our Behavior • Fundamental attribution error • How our behavior is influenced, directly or • The tendency, when analyzing others’ behaviors, to: indirectly, by the presence and/or the behavior of • overestimate the influence of personal traits AND others, the social situation • underestimate the effects of the situation • Behavior of groups • When analyzing our own behaviors we are more likely to take • Conformity; Obedience the situation into account • Social roles, norms & impact of situation • Behavior in crowds; Aggression • Example: see someone trip – think they are a klutz • But if you trip, blame it on the uneven sidewalk • Recommended leisure reading: Influence by Robert Cialdini • Social psych research on influence has provided critical data for all sorts of careers that involve influencing Social Influence: Conformity others: • Marketing & Sales In some ways we are built to conform (remember • Politics observational learning, mirror neurons) : • Fund-raising • Litigation • Management Automatic Mimicry • Behavior is contagious; what we see we often do. -

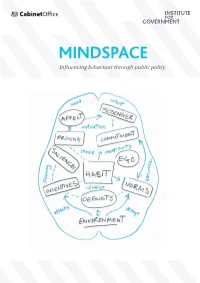

MINDSPACE: Influencing Behaviour Through Public

MINDSPACE Influencing behaviour through public policy 2 Discussion document – not a statement of government policy Contents Foreword 4 Executive Summary 7 Introduction: Understanding why we act as we do 11 MINDSPACE: A user‟s guide to what affects our behaviour 18 Examples of MINDSPACE in public policy 29 Safer communities 30 The good society 36 Healthy and prosperous lives 42 Applying MINDSPACE to policy-making 49 Public permission and personal responsibility 63 Conclusions and future challenges 73 Annexes 80-84 MINDSPACE diagram 80 New possible approaches to current policy problems 81 New frontiers of behaviour change: Insight from experts 83 References 85 Discussion document – not a statement of government policy 3 Foreword Influencing people‟s behaviour is nothing new to Government, which has often used tools such as legislation, regulation or taxation to achieve desired policy outcomes. But many of the biggest policy challenges we are now facing – such as the increase in people with chronic health conditions – will only be resolved if we are successful in persuading people to change their behaviour, their lifestyles or their existing habits. Fortunately, over the last decade, our understanding of influences on behaviour has increased significantly and this points the way to new approaches and new solutions. So whilst behavioural theory has already been deployed to good effect in some areas, it has much greater potential to help us. To realise that potential, we have to build our capacity and ensure that we have a sophisticated understanding of what does influence behaviour. This report is an important step in that direction because it shows how behavioural theory could help achieve better outcomes for citizens, either by complementing more established policy tools, or by suggesting more innovative interventions. -

The Effect of Anonymity on Conformity to Group Norms in Online Contexts: a Meta-Analysis

International Journal of Communication 10(2016), 398–415 1932–8036/20160005 The Effect of Anonymity on Conformity to Group Norms in Online Contexts: A Meta-Analysis GUANXIONG HUANG KANG LI Michigan State University, USA This research meta-analyzed 13 journal articles regarding anonymity and conformity to group norms. Results showed that there was a positive relationship between anonymity and conformity, with a weighted mean effect size = 0.16, which was in line with the social identity model of deindividuation effects. This study also investigated the differences between different types of anonymity and found that visual anonymity had a medium magnitude of effect size on conformity ( = 0.33), whereas evidence was lacking in terms of the significant effects of physical anonymity and personal information anonymity. In addition, the presence of an outgroup was also a moderator of the effect of anonymity on conformity. Studies in which participants were aware of the existence of an outgroup ( = 0.22) had larger effect sizes than those with no outgroup ( = 0.10). Keywords: depersonalization, group identification, anonymity, conformity, meta-analysis Normative social influence associated with group membership has been well studied in social psychology and group communication. Since the early days of this research stream, it has been demonstrated that anonymity has different impacts on individual judgments, depending on whether individuals are immersed in a group or not (Deusch & Gerard, 1955). Specifically, among individuals who do not compose a group, their judgments are influenced more by other people’s opinions in the identifiable setting than in the anonymous setting. However, when individuals form a group, they conform to the majority’s opinions in the anonymous situation. -

Self-Control Deindividuation Context

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2012 Running Head; Self-Control Deindividuation Context Jihye Ryu CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/130 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Running head: SELF-CONTROL IN A DEINDIVIDUATION CONTEXT 1 Self-control as a Mediator or a Moderator in a Deindividuation Context Submitted to the Department of Psychology of the City College of New York in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of master of arts in general psychology By Ji-Hye Ryu Spring 2014 SELF-CONTROL IN A DEINDIVIDUATION CONTEXT 2 Table of Contents 1. Acknowledgement ......................................................................................................................3 2. Abstract .......................................................................................................................................4 3. Introduction ................................................................................................................................5 3.1. Classical deindividuation theories .......................................................................................5 3.2. Social identity model of deindividuation effects .................................................................8 -

A Situationist Perspective on the Psychology of Evil: Understanding How Good People Are Transformed Into Perpetrators

1 A Situationist Perspective on the Psychology of Evil: Understanding How Good People Are Transformed into Perpetrators. Philip G. Zimbardo, Ph. D. (Psychology Department, Stanford University)1 Chapter in Arthur Miller (Ed.). The social psychology of good and evil: Understanding our capacity for kindness and cruelty. New York: Guilford. (Publication date: 2004). {Revised July 25, 2003} --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract I endorse a situationist perspective on the ways in which anti-social behavior by individuals, and of violence sanctioned by nations, is best understood, treated and prevented. This view has both influenced and been informed by a body of social psychological research and theory. It contrasts with the traditional dispositional perspective to explaining the whys of evil behavior. The search for internal determinants of anti-social behavior locates evil within individual predispositions – genetic “bad seeds,” personality traits, pathological risk factors, and other organismic variables. The situationist approach is to the dispositional as public health models of disease are to medical models. It follows basic principles of Lewinian theory that propel situational determinants of behavior to a foreground well beyond being merely extenuating background circumstances. Unique to this situationist approach is using experimental laboratory and field research as demonstrations of vital phenomena that other approaches only analyze verbally -

The Theories of Deindividuation Brian Li Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2010 The Theories of Deindividuation Brian Li Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Li, Brian, "The Theories of Deindividuation" (2010). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 12. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/12 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT MCKENNA COLLEGE THE THEORIES OF DEINDIVIDUATION SUBMITTED TO CRAIG BOWMAN AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY BRIAN KESTER LI FOR SENIOR THESIS FALL SEMESTER, 2010 NOVEMBER 28, 2010 Theories of Deindividuation 1 Running Head: Theories of Deindividuation Theories of Deindividuation Brian Kester Li Claremont McKenna College Theories of Deindividuation 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ….……………………………………………………………………..... 3 Abstract ………………………………………………………………………………...... 4 – 5 Chapter 1: Deindividuation Introduced …………………………………………...…….. 5 – 6 Chapter 2: The Theory of the Crowd ……...………………………………………...…... 6 – 7 Chapter 3: The Beginning of Deindividuation ...………………………………………… 7 – 8 Chapter 4: Anonymity in a Crowd …...……………………………………………...…. 8 – 12 Chapter 5: Reduced Self-awareness in a Crowd …..………………………………….. 12 – 20 Chapter 6: Pro-social Behavior and Deindividuation ……………………………….... 21 – 24 Chapter 7: The Third Theory of Deindividuation ..………………………………....… 24 – 25 Chapter 8: Conclusion ...……………………………………………………………....