Lost Labours: Where Now for the Liberal Left?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Journal of William Morris Studies

The Journal of William Morris Studies volume xx, number 3, winter 2013 Editorial – Fears and Hopes Patrick O’Sullivan 3 William Morris and Robert Browning Peter Faulkner 13 Two Williams of one medieval mind: reading the Socialist William Morris through the lens of the Radical William Cobbett David A. Kopp 31 Making daily life ‘as useful and beautiful as possible’: Georgiana Burne-Jones and Rottingdean, 1880–1904 Stephen Williams 47 William Morris: An Annotated Bibliography 2010–2011 David and Sheila Latham 66 Reviews. Edited by Peter Faulkner Michael Rosen, ed, William Morris, Poems of Protest (David Goodway) 99 Ingrid Hanson, William Morris and the Uses of Violence, 1856–1890 (Tony Pinkney) 103 The Journal of Stained Glass, vol. XXXV, 2011, Burne-Jones Special Issue. (Peter Faulkner) 106 the journal of william morris studies . winter 2013 Rosie Miles, Victorian Poetry in Context (Peter Faulkner) 110 Talia SchaVer, Novel Craft (Phillippa Bennett) 112 Glen Adamson, The Invention of Craft (Jim Cheshire) 115 Alec Hamilton, Charles Spooner (1862–1938) Arts and Crafts Architect (John Purkis) 119 Clive Aslet, The Arts and Crafts Country House: from the archives of Country Life (John Purkis) 121 Amy Woodhouse-Boulton, Transformative Beauty. Art Museums in Industrial Britain; Katherine Haskins, The Art Journal and Fine Art Publishing in Vic- torian England, 1850–1880 (Peter Faulkner) 124 Jonathan Meades, Museum without walls (Martin Stott) 129 Erratum 133 Notes on Contributors 134 Guidelines for Contributors 136 issn: 1756–1353 Editor: Patrick O’Sullivan ([email protected]) Reviews Editor: Peter Faulkner ([email protected]) Designed by David Gorman ([email protected]) Printed by the Short Run Press, Exeter, UK (http://www.shortrunpress.co.uk/) All material printed (except where otherwise stated) copyright the William Morris Society. -

Television Dramas Have Increasingly Reinforced a Picture of British Politics As ‘Sleazy’

Television dramas have increasingly reinforced a picture of British politics as ‘sleazy’ blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/new-labour-sleaze-and-tv-drama/ 4/22/2014 There were 24 TV dramas produced about New Labour and all made a unique contribution to public perceptions of politics. These dramas increasingly reinforced a picture of British politics as ‘sleazy’ and were apt to be believed by many already cynical viewers as representing the truth. Steven Fielding argues that political scientists need to look more closely at how culture is shaping the public’s view of party politics. On the evening of 28th February 2007, 4.5 million ITV viewers saw Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott receive a blowjob. Thankfully, they did not see the real Prescott on the screen but instead actor John Henshaw who played him in Confessions of a Diary Secretary. Moreover, the scene was executed with some discretion: shot from behind a sofa all viewers saw was the back of the Deputy Prime Minister’s head. Prescott’s two-year adulterous affair with civil servant Tracey Temple had been splashed across the tabloids the year before and ITV had seen fit to turn this private matter into a broad comedy, one which mixed known fact with dramatic invention. Confessions of a Diary Secretary is just one of twenty-four television dramas produced about New Labour which I discuss in my new article in the British Journal of Politics and International Relations. Some of these dramas were based on real events, others elliptically referenced the government and its personnel; but all made, I argue, a unique contribution to public perceptions of politics. -

Cultural Studies Association of Australasia Conference

Cultural Studies Association of Australasia Conference Provocations Activism | Catastrophe | Exposure Flesh | Harm | Secrets 2 - 5 December 2014 University of Wollongong lha.uow.edu.au/hsi/csaa2014 Conference hosted by: Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts, University of Wollongong and Cultural Studies Association of Australasia TABLE OF CONTENTS WELCOME ........................................................................................................................ 3 YOUR HOST ...................................................................................................................... 5 UOW CONFERENCE TEAM ................................................................................................. 6 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ....................................................................................................... 7 SPONSORS ........................................................................................................................ 7 BOOK LAUNCHES .............................................................................................................. 8 GENERAL INFORMATION ................................................................................................ 10 CONFERENCE VENUE ...................................................................................................... 12 WOLLONGONG CAMPUS MAP ........................................................................................ 13 PROGRAM OVERVIEW ................................................................................................... -

2058 ABC Festival Program 16Pp Final.Indd

abc.net.au/tv: abc.net.au/iview: For more information on Choose what to watch, when to what’s on ABC TV. watch and where to watch on our ABC free internet tv service, ABC iView. abc.net.au/tv/newsletter: To subscribe to ABC TV // Switched On, your weekly guide to the best of ABC TV. 16NOV08-27JAN09 PROGRAM CALENDAR CHECK OUT YOUR CALENDAR IN THE BACK 22058_ABC_Festival058_ABC_Festival PProgram_16pp_F2-3rogram_16pp_F2-3 22-3-3 110/10/080/10/08 88:50:07:50:07 PPMM CHECK OUT YOUR CALENDAR IN THE BACK As 2008 draws to a close A hand-picked selection of new and We’ve also crafted a special season of the In closing, I’d like to pay tribute to the acclaimed programs from Australia and crème of our award-winning Australian wonderful actors, producers, writers, and the celebratory beyond, I hope it will both entertain and dramas and documentaries including; directors, fi lmmakers, comedians, season nears, here at stimulate you over the summer months. the Constructing Australia series, researchers, and other content creators ABC TV we’ve saved ABC’s schedule is always diverse, Bastard Boys, The Sounds of Aus, with whom we have worked over the and this festival is no exception. From Crude, The Floating Brothel and past few years. Their body of work, some of our best for last, the political intrigue and treachery Rain Shadow. which you see represented here in and I am delighted to uncovered in The Howard Years, to On ABC2, relive the classic Brideshead our Festival of TV, shows how vibrant the pure entertainment of Adam Hills Revisited series, indulge in a musical and exciting the Australian creative be able to present to captured live during one of his comedy feast with the World Music Awards community is and ABC TV is delighted you our Festival of TV, shows on the road, our Festival of TV has and enjoy the premiere of Zoo Day to be the leading partner for bringing their stories and voices to the screen. -

Introduction Chapter 1

Notes Introduction 1. For The Economistt perpetuating the Patent Office myth, see April 13, 1991, page 83. 2. See Sass. 3. Book publication in 1906. 4.Swirski (2006). 5. For more on eliterary critiques and nobrow artertainment, see Swirski (2005). 6. Carlin, et al., online. 7. Reagan’s first inaugural, January 20, 1981. 8. For background and analysis, see Hess; also excellent study by Lamb. 9. This and following quote in Conason, 78. 10. BBC News, “Obama: Mitt Romney wrong.” 11. NYC cabbies in Bryson and McKay, 24; on regulated economy, Goldin and Libecap; on welfare for Big Business, Schlosser, 72, 102. 12. For an informed critique from the perspective of a Wall Street trader, see Taleb; for a frontal assault on the neoliberal programs of economic austerity and political repression, see Klein; Collins and Yeskel; documentary Walmart. 13. In Kohut, 28. 14. Orwell, 318. 15. Storey, 5; McCabe, 6; Altschull, 424. 16. Kelly, 19. 17. “From falsehood, anything follows.” 18. Calder; also Swirski (2010), Introduction. 19. In The Economist, February 19, 2011: 79. 20. Prominently Gianos; Giglio. 21. The Economistt (2011). 22. For more examples, see Swirski (2010); Tavakoli-Far. My thanks to Alice Tse for her help with the images. Chapter 1 1. In Powers, 137; parts of this research are based on Swirski (2009). 2. Haynes, 19. 168 NOTES 3. In Moyers, 279. 4. Ruderman, 10. 5. In Krassner, 276–77. 6. Green, 57; bottom of paragraph, Ruderman, 179. 7. In Zagorin, 28; next quote 30; Shakespeare did not spare the Trojan War in Troilus and Cressida. -

New Labour, Old Morality

New Labour, Old Morality. In The IdeasThat Shaped Post-War Britain (1996), David Marquand suggests that a useful way of mapping the „ebbs and flows in the struggle for moral and intellectual hegemony in post-war Britain‟ is to see them as a dialectic not between Left and Right, nor between individualism and collectivism, but between hedonism and moralism which cuts across party boundaries. As Jeffrey Weeks puts it in his contribution to Blairism and the War of Persuasion (2004): „Whatever its progressive pretensions, the Labour Party has rarely been in the vanguard of sexual reform throughout its hundred-year history. Since its formation at the beginning of the twentieth century the Labour Party has always been an uneasy amalgam of the progressive intelligentsia and a largely morally conservative working class, especially as represented through the trade union movement‟ (68-9). In The Future of Socialism (1956) Anthony Crosland wrote that: 'in the blood of the socialist there should always run a trace of the anarchist and the libertarian, and not to much of the prig or the prude‟. And in 1959 Roy Jenkins, in his book The Labour Case, argued that 'there is a need for the state to do less to restrict personal freedom'. And indeed when Jenkins became Home Secretary in 1965 he put in a train a series of reforms which damned him in they eyes of Labour and Tory traditionalists as one of the chief architects of the 'permissive society': the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality, reform of the abortion and obscenity laws, the abolition of theatre censorship, making it slightly easier to get divorced. -

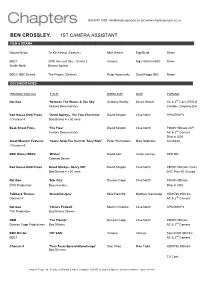

Ben Crossley. 1St Camera Assistant

020 8747 1203 | [email protected] | www.chapterspeople.co.uk ! 020 8747 1203 | [email protected] | www.chapterspeople.co.uk ! BEN CROSSLEY. 1ST CAMERA ASSISTANT FILM & DRAMA Natural Nylon ‘To Kill A King’ (Feature) Mike Barker Eigil Bryld 35mm BBC1 ‘2000 Acres of Sky’ - Series 2 Various Nigel Walters BSC 16mm Zenith North (Drama Series) BBC1/ BBC Drama ‘The Project’ (Drama) Peter Kosminsky David Higgs BSC 16mm DOCUMENTARIES PRODUCTION CO. TITLE DIRECTOR DOP FORMAT Nat Geo ‘Between The Waves & The Sky’ Anthony Wonke Simon Niblett AC & 2nd Cam, RED MX, Feature Documentary Cineflex. Ongoing-Qata Red House DOX Prods ‘David Starkys- The Two Churchills’ David Sington Clive North HPX3700 P2 / Channel 4 Doc/Drama 4 x 50 mins Beak Street Films ‘The Flaw’ David Sington Clive North F900R HDCam 24P Feature Documentary AC & 2nd Camera Shot in USA Great Western Features ‘Comic Strip-The Hunt for Tony Blair’ Peter Richardson Mike Robinson Arri Alexa / Channel 4 BBC Wales/ BBC2 ‘Whites’ David Kerr Jamie Cairney RED MX Comedy Series Red House DOX Prods David Starkys- Henry VIII' David Sington Clive North F900R HDCam/ Varicam Doc/Drama 4 x 50 mins DVC Pro HD. Europe Nat Geo ‘Star City’ Duncan Copp Clive North F900R HDCam DOX Production Documentary Shot in USA Talkback Thames ‘Grand Designs’ Mike Ratcliffe Matthew Gammage HDW790 HDCam Channel 4 AC & 2nd Camera Nat Geo ‘Christs Fireball’ Martin O’Collins Clive North HPX3700 P2 TV6 Production Doc/Drama 50mins HBO ‘The Planets’ Duncan Copp Clive North F900R HDCam Duncan Copp Productions Doc 50mins AC & 2nd Camera BBC Bristol ‘DIY SOS’ Various Various Sony F800 XDCam BBC1 AC & 2nd Camera Channel 4 ‘Time Team Special-Stonehenge’ Sian Price Mike Todd HDW790 HDCam Doc 50 mins CV Cont…… Chapters People Ltd. -

Labour's Next Majority Means Winning Over Conservative Voters but They Are Not Likely to Be the Dominant Source of The

LABOUR’S NEXT MAJORITY THE 40% STRATEGY Marcus Roberts LABOUR’S The 40% There will be voters who go to the polls on 6th May 2015 who weren’t alive strategy when Tony and Cherie Blair posed outside 10 Downing Street on 1st May NEXT 1997. They will have no memory of an event which is a moment of history as distant from them as Margaret Thatcher’s 1979 election victory was for the voters of 1997. If Ed Miliband seeks to emulate what Blair did in 1997, he too must build his own political majority for the era in which he seeks to govern. MAJORITY This report sets out a plausible strategy for Labour’s next majority, one that is secured through winning 40 per cent of the popular vote in May 2015, despite the challenges of a fragmenting electorate. It also challenges the Marcus Roberts party at all levels to recognise that the 40 per cent strategy for a clear majority in 2015 will require a different winning formula to that which served New Labour so well a generation ago, but which is past its sell-by date in a different political and economic era. A FABIAN REPORT ISBN 978 0 7163 7004 8 ABOUT THE FABIAN SOCIETY The Fabian Society is Britain’s oldest political think tank. Since 1884 the society has played a central role in developing political ideas and public policy on the left. It aims to promote greater equality of wealth, power and opportunity; the value of collective public action; a vibrant, tolerant and accountable democracy; citizenship, liberty and human rights; sustainable development; and multilateral international cooperation. -

Feral Beast": Cautionary Lessons from British Press Reform Lili Levi University of Miami School of Law, [email protected]

University of Miami Law School University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository Articles Faculty and Deans 2015 Taming the "Feral Beast": Cautionary Lessons From British Press Reform Lili Levi University of Miami School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/fac_articles Part of the Communications Law Commons, and the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation Lili Levi, Taming the "Feral Beast": Cautionary Lessons From British Press Reform, 55 Santa Clara L. Rev. 323 (2015). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty and Deans at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TAMING THE "FERAL BEAST"1 : CAUTIONARY LESSONS FROM BRITISH PRESS REFORM Lili Levi* TABLE OF CONTENTS Introdu ction ............................................................................ 324 I. British Press Reform, in Context ....................................... 328 A. Overview of the British Press Sector .................... 328 B. The British Approach to Newspaper Regulation.. 330 C. Phone-Hacking and the Leveson Inquiry Into the Culture, Practices and Ethics of the Press ..... 331 D. Where Things Stand Now ...................................... 337 1. The Royal Charter ............................................. 339 2. IPSO and IM -

Conference Round-Up

Conferences 2015 Connect’s round-up of the 2015 Party Conferences conference round-up As the Tories gathered in Manchester for their first post-victory making some MPs anxious – and a harder line than Cameron’s conference since 1992 some predicted a jubilant atmosphere. on the EU. Theresa May’s tough talking on immigration might Instead the conference had a calm and serious feel to it, with have pushed the right buttons for some delegates but went the Prime Minister and Chancellor keen to convey a sense of down badly in the media, who portrayed it as a tilt to the right a government getting back down to work. Last year the Tories and out of keeping with the general tone of the conference. were high, geed up for the coming election – as one journalist told us, “we can see you’re in good spirits, but we think you As the party moves from a surprise election victory to a phase of drunk the kool-aid”. In contrast the 2015 conference moved at a implementation this was a conference for a political force that steady pace to the drumbeat of Security-Stability-Opportunity. doesn’t want to lose power any time soon. Tory excitement at winning is tempered by the knowledge that unpopular decisions The Chancellor, burnishing his credentials for the top-job, lie ahead. They know that they remain unliked by many voters, unveilled bold policies such as the devolution of business rates and are still sensitive to the charge of being the ‘nasty’ party. to local councils. In a calculated manoeuvre to signal the Tory Most opponents in Manchester were peaceful but publicity pitch to the centre, he appointed a prominent Labour ‘Blairite’, focussed on more extreme elements who hurled abuse and Lord Adonis as head of the newly created National Infrastructure eggs at conference attendees. -

Conference Agenda and Directory Newcastlegateshead 9Th–11Th March 2012

spring conference agenda and directory newcastlegateshead 9th–11th march 2012 in government on your side Welcome to the Conference Agenda and Directory for the Liberal Democrat spring contents 2012 federal conference – your guide to all that is taking place at conference. Features: 3–6 If you have any questions whilst at conference Getting on with the job please ask a conference steward or go to the by Nick Clegg MP 3 conference Information Desk, located on the Join in the renaissance of Concourse of The Sage Gateshead. NewcastleGateshead by John Shipley 5 Be bold and unashamed liberals conference venue by Tim Farron MP 6 All conference sessions and fringe events for spring conference will take place in The Sage Gateshead. Conference information: 7–16 Venue and exhibition plan 16 The Sage Gateshead St Mary’s Square, Gateshead Quays Exhibition 17–20 Gateshead, NE8 2JR www.thesagegateshead.org Fringe guide: 21–29 The conference centre will open at 14.00 on Friday. Friday fringe 22 There is a map of NewcastleGateshead on the Saturday fringe 24 back cover and a plan of the venue on page 16. Conference training programme 28–29 conference hotel Agenda: 30–53 Agenda index and timetable 30 The conference hotel is the Hilton Newcastle Gateshead. Friday 9th March 31 Saturday 10th March 32 Hilton Newcastle Gateshead Bottle Bank, Gateshead, NE8 2AR Sunday 11th March 47 0191 490 9700 Autumn 2012 conference timetable 53 www.hilton.co.uk/newcastlegateshead Standing orders 54–61 Federal Party 61 For conference details and registration online: www.libdems.org.uk/springconference Map of NewcastleGateshead back cover Scan this to access the Conference Agenda and Directory online: ISBN 978-1-907046-45-2 Published by The Conference Office, Liberal Democrats, 8–10 Great George Street, London SW1P 3AE. -

67 Summer 2010

For the study of Liberal, SDP and Issue 67 / Summer 2010 / £10.00 Liberal Democrat history Journal of LiberalHI ST O R Y Liberals and the left Matthew Roberts Out of Chartism, into Liberalism Popular radicals and the Liberal Party Michael Freeden The Liberal Party and the New Liberalism John Shepherd The flight from the Liberal PartyLiberals who joined Labour, 1914–31 Matt Cole ‘An out-of-date word’ Jo Grimond and the left Peter Hellyer The Young Liberals and the left, 1965–70 Liberal Democrat History Group Liberal Leaders The latest publication from the Liberal Democrat History Group is Liberal Leaders: Leaders of the Liberal Party, SDP and Liberal Democrats since 1900. The sixty-page booklet contains concise biographies of every Liberal, Social Democrat and Liberal Democrat leader since 1900. The total of sixteen biographies stretches from Henry Campbell-Bannerman to Nick Clegg, including such figures as H. H. Asquith, David Lloyd George, Jo Grimond, David Steel, David Owen and Paddy Ashdown. Liberal Leaders is available to Journal of Liberal History subscribers for the special price of £5 (normal price £6) with free p&p. To order, please send a cheque for £5.00 (made out to ‘Liberal Democrat History Group’) to LDHG, 38 Salford Road, London SW2 4BQ. RESEARCH IN PROGRESS If you can help any of the individuals listed below with sources, contacts, or any other information — or if you know anyone who can — please pass on details to them. Details of other research projects in progress should be sent to the Editor (see page 3) for inclusion here.