Mashantucket Pequot Plant Use from 1675-1800 AD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Exchange of Body Parts in the Pequot War

meanes to "A knitt them togeather": The Exchange of Body Parts in the Pequot War Andrew Lipman was IN the early seventeenth century, when New England still very new, Indians and colonists exchanged many things: furs, beads, pots, cloth, scalps, hands, and heads. The first exchanges of body parts a came during the 1637 Pequot War, punitive campaign fought by English colonists and their native allies against the Pequot people. the war and other native Throughout Mohegans, Narragansetts, peoples one gave parts of slain Pequots to their English partners. At point deliv so eries of trophies were frequent that colonists stopped keeping track of to individual parts, referring instead the "still many Pequods' heads and Most accounts of the war hands" that "came almost daily." secondary as only mention trophies in passing, seeing them just another grisly were aspect of this notoriously violent conflict.1 But these incidents a in at the Andrew Lipman is graduate student the History Department were at a University of Pennsylvania. Earlier versions of this article presented graduate student conference at the McNeil Center for Early American Studies in October 2005 and the annual conference of the South Central Society for Eighteenth-Century comments Studies in February 2006. For their and encouragement, the author thanks James H. Merrell, David Murray, Daniel K. Richter, Peter Silver, Robert Blair St. sets George, and Michael Zuckerman, along with both of conference participants and two the anonymous readers for the William and Mary Quarterly. 1 to John Winthrop, The History ofNew England from 1630 1649, ed. James 1: Savage (1825; repr., New York, 1972), 237 ("still many Pequods' heads"); John Mason, A Brief History of the Pequot War: Especially Of the memorable Taking of their Fort atMistick in Connecticut In 1637 (Boston, 1736), 17 ("came almost daily"). -

Learning from Foxwoods Visualizing the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation

Learning from Foxwoods Visualizing the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation bill anthes Since the passage in 1988 of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, which recognized the authority of Native American tribal groups to operate gaming facilities free from state and federal oversight and taxation, gam- bling has emerged as a major industry in Indian Country. Casinos offer poverty-stricken reservation communities confined to meager slices of marginal land unprecedented economic self-sufficiency and political power.1 As of 2004, 226 of 562 federally recognized tribal groups were in the gaming business, generating a total of $16.7 billion in gross annual revenues.2 During the past two decades the proceeds from tribally owned bingo halls, casinos, and the ancillary infrastructure of a new, reserva- tion-based tourist industry have underwritten educational programs, language and cultural revitalization, social services, and not a few suc- cessful Native land claims. However, while these have been boom years in many ways for some Native groups, these same two decades have also seen, on a global scale, the obliteration of trade and political barriers and the creation of frictionless markets and a geographically dispersed labor force, as the flattening forces of the marketplace have steadily eroded the authority of the nation as traditionally conceived. As many recent commentators have noted, deterritorialization and disorganization are endemic to late capitalism.3 These conditions have implications for Native cultures. Plains Cree artist, critic, and curator Gerald McMaster has asked, “As aboriginal people struggle to reclaim land and to hold onto their present land, do their cultural identities remain stable? When aboriginal government becomes a reality, how will the local cultural identities act as centers for nomadic subjects?”4 Foxwoods Casino, a vast and highly profitable gam- ing, resort, and entertainment complex on the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation in southwestern Connecticut, might serve as a test case for McMaster’s question. -

William Bradford Makes His First Substantial

Ed The Pequot Conspirator White William Bradford makes his first substantial ref- erence to the Pequots in his account of the 1628 Plymouth Plantation, in which he discusses the flourishing of the “wampumpeag” (wam- pum) trade: [S]trange it was to see the great alteration it made in a few years among the Indians themselves; for all the Indians of these parts and the Massachusetts had none or very little of it, but the sachems and some special persons that wore a little of it for ornament. Only it was made and kept among the Narragansetts and Pequots, which grew rich and potent by it, and these people were poor and beggarly and had no use of it. Neither did the English of this Plantation or any other in the land, till now that they had knowledge of it from the Dutch, so much as know what it was, much less that it was a com- modity of that worth and value.1 Reading these words, it might seem that Bradford’s understanding of Native Americans has broadened since his earlier accounts of “bar- barians . readier to fill their sides full of arrows than otherwise.”2 Could his 1620 view of them as undifferentiated, arrow-hurtling sav- ages have been superseded by one that allowed for the economically complex diversity of commodity-producing traders? If we take Brad- ford at his word, the answer is no. For “Indians”—the “poor and beg- garly” creatures Bradford has consistently described—remain present in this description but are now joined by a different type of being who have been granted proper names, are “rich and potent” compared to “Indians,” and are perhaps superior to the English in mastering the American Literature, Volume 81, Number 3, September 2009 DOI 10.1215/00029831-2009-022 © 2009 by Duke University Press Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/american-literature/article-pdf/81/3/439/392273/AL081-03-01WhiteFpp.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 440 American Literature economic lay of the land. -

The Wawaloam Monument

A Rock of Remembrance Rhode Island Historical Cemetery EX056, also known as the “Indian Rock Cemetery,” isn’t really a cemetery at all. There are no burials at the site, only a large engraved boulder in memory of Wawaloam and her husband Miantinomi, Narragansett Indians. Sidney S. Rider, the Rhode Island bookseller and historian, collates most of the information known about Wawaloam. She was the daughter of Sequasson, a sachem living near a Connecticut river and an ally of Miantinomi. That would mean she was of the Nipmuc tribe whose territorial lands lay to the northwest of Narragansett lands. Two other bits of information suggest her origin. First, her name contains an L, a letter not found in the Narragansett language. Second, there is a location in formerly Nipmuc territory and presently the town of Glocester, Rhode Island that was called Wawalona by the Indians. The meaning of her name is uncertain, but Rider cites a “scholar learned in defining the meaning of Indian words” who speculates that it derives from the words Wa-wa (meaning “round about”) and aloam (meaning “he flies’). Together they are thought to describe the flight of a swallow as it flies over the fields. The dates of Wawaloam’s birth and death are unknown. History records that in 1632 she and Miantinomi traveled to Boston and visited Governor John Winthrop of the Massachusetts Colony at his house (Winthrop’s History of New England, vol. 1). The last thing known of her is an affidavit she signed in June 1661 at her village of Aspanansuck (Exeter Hill on the Ten Rod Road). -

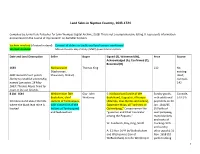

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country.Pdf

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country, 1643-1724 Compiled by Jenny Hale Pulsipher for John Wompas Digital Archive, 2018. This is not a comprehensive listing. It represents information encountered in the course of my research on Swindler Sachem. Sachem involved (if noted in deed) Consent of elders or traditional land owners mentioned Woman involved Massachusetts Bay Colony (MBC) government actions Date and Land Description Seller Buyer Signed (S), Witnessed (W), Price Source Acknowledged (A), ConFirmed (C), Recorded (R) 1643 Nashacowam Thomas King £12 No [Nashoonan, existing MBC General Court grants Shawanon, Sholan] deed; liberty to establish a township, Connole, named Lancaster, 18 May 142 1653; Thomas Noyes hired by town to lay out bounds. 8 Oct. 1644 Webomscom [We Gov. John S: Nodowahunt [uncle of We Sundry goods, Connole, Bucksham, chief Winthrop Bucksham], Itaguatiis, Alhumpis with additional 143-145 10 miles round about the hills sachem of Tantiusques, [Allumps, alias Hyems and James], payments on 20 where the black lead mine is with consent of all the Sagamore Moas, all “sachems of Jan. 1644/45 located Indians at Tantiusques] Quinnebaug,” Cassacinamon the (10 belts of and Nodowahunt “governor and Chief Councelor wampampeeg, among the Pequots.” many blankets and coats of W: Sundanch, Day, King, Smith trucking cloth and sundry A: 11 Nov. 1644 by WeBucksham other goods); 16 and Washcomos (son of Nov. 1658 (10 WeBucksham) to John Winthrop Jr. yards trucking 1 cloth); 1 March C: 20 Jan. 1644/45 by Washcomos 1658/59 to Amos Richardson, agent for John Winthrop Jr. (JWJr); 16 Nov. 1658 by Washcomos to JWJr.; 1 March 1658/59 by Washcomos to JWJr 22 May 1650 Connole, 149; MD, MBC General Court grants 7:194- 3200 acres in the vicinity of 195; MCR, LaKe Quinsigamond to Thomas 4:2:111- Dudley, esq of Boston and 112 Increase Nowell of Charleston [see 6 May and 28 July 1657, 18 April 1664, 9 June 1665]. -

The Pequots and the Puritans of the 17Th Century

Alfred A. Cave. The Pequot War. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1996. ix + 219 pp. $45.00, cloth, ISBN 978-1-55849-029-1. Reviewed by Robert E. Weir Published on H-PCAACA (October, 1996) Hurtling east from Norwich, Connecticut, one His thesis is straightforward: "The Pequot War in encounters an entreprenurial wonder, the giant reality was the messy outgrowth of petty squab‐ Foxwoods Casino owned by the Mashantucket Pe‐ bles over trade, tribute, and land among Pequots, quot Indians. In addition to the resort, the area is Mohegans, River Indians, Niantics, Narragansetts, dotted with clinics, Indian schools, golf courses, Dutch traders, and English Puritans" (p. 178). But and gleaming new housing complexes financed by what sets Caves' work apart from others is the mostly non-Indian gamblers. emphasis he puts on how the Puritans trans‐ This is remarkable given that 360 years ago formed "petty squabbles" into "a cosmic struggle the Pequots were nearly the victims of total geno‐ of good and evil in the wilderness" (p. 178). cide. In a well-written and meticulously re‐ Cave shows how Puritans were constrained searched new book, Alfred Cave details that earli‐ by a bipolar cosmology. Despite pre-settlement vi‐ er tragedy. In 1636, New England Puritans and In‐ sions of living in harmony with Indians, Puri‐ dian allies launched a full-scale assault on the Pe‐ tanism had little respect for cultural diversity. The quots. By 1637, a substantial portion of the Pequot founders of Massachusetts Bay divided the world nation lay dead or was bound for slavery in the into the Godly and the damned. -

The Pequot War

The Pequot War The Native Americans and the English settlers were on a collision course. In the early 1600s, more than 8,000 Pequots lived in southeastern Connecticut. They traded with the Dutch. The Pequots controlled the fur and wampum trade. Their strong leaders and communities controlled tribes across southern New England. It was a peaceful time between 1611 and 1633. But all was not well. Contact with Europeans during this period brought a deadly disease. Smallpox killed half of the Pequots by 1635. The English arrived in 1633. The English wanted to trade with the Native Americans, too. The Dutch and Pequots tried to stay in control of all trade. This led to misunderstanding, conflict, and violence. In the summer of 1634, a Virginia trader and his crew sailed up the Connecticut River. They took captive several Pequots as guides. It’s not clear what happened or why, but the Virginia trader and crew were killed. The English wanted the Pequots punished for the crime. They attacked and burned a Pequot village on the Thames River and killed several Pequots. The Pequots fought back. All winter and spring of 1637 the Pequot attacked anyone who left the English fort at Saybrook Point. They destroyed food and supplies. They stopped any boats from sailing up the river to Windsor, Wethersfield, and Hartford. More than 20 English soldiers were killed. © Connecticut Explored Inc. Massachusetts sent 20 soldiers to help the English soldiers at Saybrook Point. Then the Pequots attacked Wethersfield. They killed nine men and two women and captured two girls. -

Living in the New World

February 15 – May 6, 2018 A Special Collections Exhibition at Pequot Library LIVING IN THE NEW WORLD Exhibition Guide Living in the New World CONTENTS Thoughts .................................................................................................................................................................................. - 3 - Discussion Topics ..................................................................................................................................................................... - 6 - Vocabulary ............................................................................................................................................................................... - 7 - Suggested Reading .................................................................................................................................................................. - 9 - Reading List for Young People ............................................................................................................................................. - 9 - Reading List for the perpetually Young: ................................................................................................................................ - 9 - Internet Resources ................................................................................................................................................................ - 11 - Timeline ................................................................................................................................................................................ -

The Role of the Narragansetts in the Breakdown of Anglo-Native Relations During King Philip’S War Lauren Sagar Providence College

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@Providence Providence College DigitalCommons@Providence History Student Papers History Spring 2012 New World Rivals: The Role of the Narragansetts in the Breakdown of Anglo-Native Relations During King Philip’s War Lauren Sagar Providence College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.providence.edu/history_students Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Sagar, Lauren, "New World Rivals: The Role of the Narragansetts in the rB eakdown of Anglo-Native Relations During King Philip’s War" (2012). History Student Papers. Paper 5. http://digitalcommons.providence.edu/history_students/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at DigitalCommons@Providence. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Student Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Providence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. New World Rivals: The Role of the Narragansetts in the Breakdown of Anglo-Native Relations During King Philip’s War Lauren Sagar HIS 490 History Honors Thesis Department of History Providence College Fall 2011 I beseech you consider, how the name of the most holy and jealous God may be preserved between the clashings of these two... the glorious conversion of the Indians in New England and the unnecessary wars and cruel destructions of the Indians in New England. -Roger Williams to the General Court of Massachusetts Bay, -

The Role of the Narragansetts in the Breakdown of Anglo-Native Relations During King Philip’S War

Providence College DigitalCommons@Providence History & Classics Undergraduate Theses History & Classics 12-15-2011 New World Rivals: The Role of the Narragansetts in the Breakdown of Anglo-Native Relations During King Philip’s War Lauren Sagar Providence College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/history_undergrad_theses Part of the United States History Commons Sagar, Lauren, "New World Rivals: The Role of the Narragansetts in the Breakdown of Anglo-Native Relations During King Philip’s War" (2011). History & Classics Undergraduate Theses. 28. https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/history_undergrad_theses/28 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History & Classics at DigitalCommons@Providence. It has been accepted for inclusion in History & Classics Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Providence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. New World Rivals: The Role of the Narragansetts in the Breakdown of Anglo-Native Relations During King Philip’s War Lauren Sagar HIS 490 History Honors Thesis Department of History Providence College Fall 2011 I beseech you consider, how the name of the most holy and jealous God may be preserved between the clashings of these two... the glorious conversion of the Indians in New England and the unnecessary wars and cruel destructions of the Indians in New England. -Roger Williams to the General Court of Massachusetts Bay, 1654 CONTENTS GLOSSARY .................................................................................................................................. -

Wampumpeag| the Impact of the 17Th Century Wampum Trade on Native Culture in Southern New England and New Netherlands

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1996 Wampumpeag| The impact of the 17th century wampum trade on native culture in southern New England and New Netherlands George R. Price The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Price, George R., "Wampumpeag| The impact of the 17th century wampum trade on native culture in southern New England and New Netherlands" (1996). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4042. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4042 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of IVIONXANA. Permission is granted by tlie author to reproduce tliis material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ** Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature ** Yes, I grant permission ^ No, I do not grant pennission Author's Signature ^ Date P^ C. Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. Wampumpeag: The Impact of the 17th Century Wampum Trade on Native Culture in Southern New England and New Netherlands by George R. -

The Captivity of Pequot Women and Children After the War of 1637 Author(S): Michael L

"They Could Not Endure That Yoke": The Captivity of Pequot Women and Children after the War of 1637 Author(s): Michael L. Fickes Reviewed work(s): Source: The New England Quarterly, Vol. 73, No. 1 (Mar., 2000), pp. 58-81 Published by: The New England Quarterly, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/366745 . Accessed: 02/11/2011 21:32 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The New England Quarterly, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The New England Quarterly. http://www.jstor.org "They Could Not Endure That Yoke": The Captivityof Pequot Women and Children after the War of 1637 MICHAEL L. FICKES CCOUNTSof AmericanIndians abducting white New En- A glanders have captured the attention of scholars for over three centuries, yet little interest has been shown in a much more common phenomenon-Indians' captivityamong whites.' In the first major military engagement of the Pequot War, white New Englanders and their Algonquian allies launched a surprise, pre-dawn assault on a Pequot community near the Mystic River. In the end, they had stabbed, shot, and burned to death between 300 and 700 Pequot men, women, and children.