The Pequot War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Exchange of Body Parts in the Pequot War

meanes to "A knitt them togeather": The Exchange of Body Parts in the Pequot War Andrew Lipman was IN the early seventeenth century, when New England still very new, Indians and colonists exchanged many things: furs, beads, pots, cloth, scalps, hands, and heads. The first exchanges of body parts a came during the 1637 Pequot War, punitive campaign fought by English colonists and their native allies against the Pequot people. the war and other native Throughout Mohegans, Narragansetts, peoples one gave parts of slain Pequots to their English partners. At point deliv so eries of trophies were frequent that colonists stopped keeping track of to individual parts, referring instead the "still many Pequods' heads and Most accounts of the war hands" that "came almost daily." secondary as only mention trophies in passing, seeing them just another grisly were aspect of this notoriously violent conflict.1 But these incidents a in at the Andrew Lipman is graduate student the History Department were at a University of Pennsylvania. Earlier versions of this article presented graduate student conference at the McNeil Center for Early American Studies in October 2005 and the annual conference of the South Central Society for Eighteenth-Century comments Studies in February 2006. For their and encouragement, the author thanks James H. Merrell, David Murray, Daniel K. Richter, Peter Silver, Robert Blair St. sets George, and Michael Zuckerman, along with both of conference participants and two the anonymous readers for the William and Mary Quarterly. 1 to John Winthrop, The History ofNew England from 1630 1649, ed. James 1: Savage (1825; repr., New York, 1972), 237 ("still many Pequods' heads"); John Mason, A Brief History of the Pequot War: Especially Of the memorable Taking of their Fort atMistick in Connecticut In 1637 (Boston, 1736), 17 ("came almost daily"). -

MASSACHUSETTS: Or the First Planters of New-England, the End and Manner of Their Coming Thither, and Abode There: in Several EPISTLES (1696)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Joshua Scottow Papers Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 1696 MASSACHUSETTS: or The first Planters of New-England, The End and Manner of their coming thither, and Abode there: In several EPISTLES (1696) John Winthrop Governor, Massachusetts Bay Colony Thomas Dudley Deputy Governor, Massachusetts Bay Colony John Allin Minister, Dedham, Massachusetts Thomas Shepard Minister, Cambridge, Massachusetts John Cotton Teaching Elder, Church of Boston, Massachusetts See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/scottow Part of the American Studies Commons Winthrop, John; Dudley, Thomas; Allin, John; Shepard, Thomas; Cotton, John; Scottow, Joshua; and Royster,, Paul Editor of the Online Electronic Edition, "MASSACHUSETTS: or The first Planters of New- England, The End and Manner of their coming thither, and Abode there: In several EPISTLES (1696)" (1696). Joshua Scottow Papers. 7. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/scottow/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Joshua Scottow Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors John Winthrop; Thomas Dudley; John Allin; Thomas Shepard; John Cotton; Joshua Scottow; and Paul Royster, Editor of the Online Electronic Edition This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ scottow/7 ABSTRACT CONTENTS In 1696 there appeared in Boston an anonymous 16mo volume of 56 pages containing four “epistles,” written from 66 to 50 years earlier, illustrating the early history of the colony of Massachusetts Bay. -

STATIONERY Pine Logs Wanted ADVERTISE

•Sw:-''r' :v-:^ •'V ;.%*i- .-; •••'•'«..•';.•.'•' ,'•''• •*i-'-V'*-''•*•'••%'••'•?•* ••-'^'•''••'v'" L?' ^ep0ftef VOLUME XXXVIII NO. 14 ANTRIM, NEW HAMPSHIRE, WEDNESDAY, MARCH 16. 1921 5 CENTS A COPY PBECmcniEETIIIG miTiVE o^miM A FEW JOUGHTS RELIEF inHELAHD Americanism Be Business Fof the Ensuing Passes From TIlis Life at Syggested by What Is An Apallo be Maile in LEONARDWOOD Keaf Tfansacted Her Daughter's Home Happening Around liberty ezisU iit proportios - This Vicinity to wboleaoosc rastrsiat.—DaD- id WeEister: Spseeli Mcy tO. On Satarday, March 12, at 1.80 p. On^Wedn -^y'evening last, at En Will the Legislatore adjonm by On March 17, St. Patrick's Day. 1847. : m., the faneral of. Mrs. Herbert H. gine ball, the annual Precinct nweting April firat? According to the sUte there will be inaugurated an appeal to Whittle (Caroline Elizabeth Jameson) IE quoted words trom M onf ter- ment by those wbo claim to know bow the American peopla to aid in the re was beld. Owing to tbe very heavy was beld at her old home here, on the Tan- but anotber way of si.v'ngi much work there is lo do, it is safe lief of the soffering women and child rain the company of men wbo gather spot where sbe was bom Aog. 23, that liberty does not mean llri^nsf*. "; he to say tbst it will be well into the ren of Ireland. Tbls movement has ed was small, aronnd tbirty being pres 1860. tbougbt expressed In simiiJc nmls STATIONERY montb before adjournment is Uken. tbe approval of the highest anthori- should liave a place In Oie FrlnuT of ent. -

Apples Abound

APPLES ABOUND: FARMERS, ORCHARDS, AND THE CULTURAL LANDSCAPES OF AGRARIAN REFORM, 1820-1860 A Dissertation Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy John Henris May, 2009 APPLES ABOUND: FARMERS, ORCHARDS, AND THE CULTURAL LANDSCAPES OF AGRARIAN REFORM, 1820-1860 John Henris Dissertation Approved: Accepted: ____________________________ ____________________________ Advisor Department Chair Dr. Kevin Kern Dr. Michael M. Sheng ____________________________ ____________________________ Committee Member Dean of the College Dr. Lesley J. Gordon Dr. Chand Midha ____________________________ ____________________________ Committee Member Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Kim M. Gruenwald Dr. George R. Newkome ____________________________ ____________________________ Committee Member Date Dr. Elizabeth Mancke ____________________________ Committee Member Dr. Randy Mitchell ____________________________ Committee Member Dr. Gregory Wilson ii ABSTRACT This dissertation argues that apple cultivation was invariably intertwined with, and shaped by, the seemingly discordant threads of scientific agricultural specialization, emigration, urbanization, sectionalism, moral reform, and regional identity in New England and Ohio prior to the American Civil War. As the temperance cause gained momentum during the 1820s many farmers abandoned their cider trees and transitioned to the cultivation of grafted winter apples in New England. In turn agricultural writers used -

(King Philip's War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial

Connecticut Unscathed: Victory in The Great Narragansett War (King Philip’s War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Major Jason W. Warren, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin Jr., Advisor Alan Gallay, Kristen Gremillion Peter Mansoor, Geoffrey Parker Copyright by Jason W. Warren 2011 Abstract King Philip’s War (1675-1676) was one of the bloodiest per capita in American history. Although hostile native groups damaged much of New England, Connecticut emerged unscathed from the conflict. Connecticut’s role has been obscured by historians’ focus on the disasters in the other colonies as well as a misplaced emphasis on “King Philip,” a chief sachem of the Wampanoag groups. Although Philip formed the initial hostile coalition and served as an important leader, he was later overshadowed by other sachems of stronger native groups such as the Narragansetts. Viewing the conflict through the lens of a ‘Great Narragansett War’ brings Connecticut’s role more clearly into focus, and indeed enables a more accurate narrative for the conflict. Connecticut achieved success where other colonies failed by establishing a policy of moderation towards the native groups living within its borders. This relationship set the stage for successful military operations. Local native groups, whether allied or neutral did not assist hostile Indians, denying them the critical intelligence necessary to coordinate attacks on Connecticut towns. The English colonists convinced allied Mohegan, Pequot, and Western Niantic warriors to support their military operations, giving Connecticut forces a decisive advantage in the field. -

Learning from Foxwoods Visualizing the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation

Learning from Foxwoods Visualizing the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation bill anthes Since the passage in 1988 of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, which recognized the authority of Native American tribal groups to operate gaming facilities free from state and federal oversight and taxation, gam- bling has emerged as a major industry in Indian Country. Casinos offer poverty-stricken reservation communities confined to meager slices of marginal land unprecedented economic self-sufficiency and political power.1 As of 2004, 226 of 562 federally recognized tribal groups were in the gaming business, generating a total of $16.7 billion in gross annual revenues.2 During the past two decades the proceeds from tribally owned bingo halls, casinos, and the ancillary infrastructure of a new, reserva- tion-based tourist industry have underwritten educational programs, language and cultural revitalization, social services, and not a few suc- cessful Native land claims. However, while these have been boom years in many ways for some Native groups, these same two decades have also seen, on a global scale, the obliteration of trade and political barriers and the creation of frictionless markets and a geographically dispersed labor force, as the flattening forces of the marketplace have steadily eroded the authority of the nation as traditionally conceived. As many recent commentators have noted, deterritorialization and disorganization are endemic to late capitalism.3 These conditions have implications for Native cultures. Plains Cree artist, critic, and curator Gerald McMaster has asked, “As aboriginal people struggle to reclaim land and to hold onto their present land, do their cultural identities remain stable? When aboriginal government becomes a reality, how will the local cultural identities act as centers for nomadic subjects?”4 Foxwoods Casino, a vast and highly profitable gam- ing, resort, and entertainment complex on the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation in southwestern Connecticut, might serve as a test case for McMaster’s question. -

William Bradford Makes His First Substantial

Ed The Pequot Conspirator White William Bradford makes his first substantial ref- erence to the Pequots in his account of the 1628 Plymouth Plantation, in which he discusses the flourishing of the “wampumpeag” (wam- pum) trade: [S]trange it was to see the great alteration it made in a few years among the Indians themselves; for all the Indians of these parts and the Massachusetts had none or very little of it, but the sachems and some special persons that wore a little of it for ornament. Only it was made and kept among the Narragansetts and Pequots, which grew rich and potent by it, and these people were poor and beggarly and had no use of it. Neither did the English of this Plantation or any other in the land, till now that they had knowledge of it from the Dutch, so much as know what it was, much less that it was a com- modity of that worth and value.1 Reading these words, it might seem that Bradford’s understanding of Native Americans has broadened since his earlier accounts of “bar- barians . readier to fill their sides full of arrows than otherwise.”2 Could his 1620 view of them as undifferentiated, arrow-hurtling sav- ages have been superseded by one that allowed for the economically complex diversity of commodity-producing traders? If we take Brad- ford at his word, the answer is no. For “Indians”—the “poor and beg- garly” creatures Bradford has consistently described—remain present in this description but are now joined by a different type of being who have been granted proper names, are “rich and potent” compared to “Indians,” and are perhaps superior to the English in mastering the American Literature, Volume 81, Number 3, September 2009 DOI 10.1215/00029831-2009-022 © 2009 by Duke University Press Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/american-literature/article-pdf/81/3/439/392273/AL081-03-01WhiteFpp.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 440 American Literature economic lay of the land. -

The Wawaloam Monument

A Rock of Remembrance Rhode Island Historical Cemetery EX056, also known as the “Indian Rock Cemetery,” isn’t really a cemetery at all. There are no burials at the site, only a large engraved boulder in memory of Wawaloam and her husband Miantinomi, Narragansett Indians. Sidney S. Rider, the Rhode Island bookseller and historian, collates most of the information known about Wawaloam. She was the daughter of Sequasson, a sachem living near a Connecticut river and an ally of Miantinomi. That would mean she was of the Nipmuc tribe whose territorial lands lay to the northwest of Narragansett lands. Two other bits of information suggest her origin. First, her name contains an L, a letter not found in the Narragansett language. Second, there is a location in formerly Nipmuc territory and presently the town of Glocester, Rhode Island that was called Wawalona by the Indians. The meaning of her name is uncertain, but Rider cites a “scholar learned in defining the meaning of Indian words” who speculates that it derives from the words Wa-wa (meaning “round about”) and aloam (meaning “he flies’). Together they are thought to describe the flight of a swallow as it flies over the fields. The dates of Wawaloam’s birth and death are unknown. History records that in 1632 she and Miantinomi traveled to Boston and visited Governor John Winthrop of the Massachusetts Colony at his house (Winthrop’s History of New England, vol. 1). The last thing known of her is an affidavit she signed in June 1661 at her village of Aspanansuck (Exeter Hill on the Ten Rod Road). -

Creating an American Identity

Creating an American Identity 9780230605268ts01.indd i 4/24/2008 12:26:30 PM This page intentionally left blank Creating an American Identity New England, 1789–1825 Stephanie Kermes 9780230605268ts01.indd iii 4/24/2008 12:26:30 PM CREATING AN AMERICAN IDENTITY Copyright © Stephanie Kermes, 2008. All rights reserved. First published in 2008 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN™ 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 and Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England RG21 6XS Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN-13: 978–0–230–60526–8 ISBN-10: 0–230–60526–5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kermes, Stephanie. Creating an American identity : New England, 1789–1825 / Stephanie Kermes. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–230–60526–5 1. New England—Civilization—18th century. 2. New England— Civilization—19th century. 3. Regionalism—New England—History. 4. Nationalism—New England—History. 5. Nationalism—United States—History. 6. National characteristics, American—History. 7. Popular culture—New England—History. 8. Political culture—New England—History. 9. New England—Relations—Europe. 10. Europe— Relations—New England. I. Title. F8.K47 2008 974Ј.03—dc22 2007048026 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Design by Newgen Imaging Systems (P) Ltd., Chennai, India. First edition: July 2008 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America. -

Thomas S. Kidd, “'The Devil and Father Rallee': the Narration of Father Rale's War in Provincal Massachusetts” Histori

Thomas S. Kidd, “’The Devil and Father Rallee’: The Narration of Father Rale’s War in Provincal Massachusetts” Historical Journal of Massachusetts Volume 30, No. 2 (Summer 2002). Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/ number/ date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.westfield.ma.edu/mhj/.” Editor, Historical Journal of Massachusetts c/o Westfield State University 577 Western Ave. Westfield MA 01086 “The Devil and Father Rallee”: The Narration of Father Rale’s War in Provincial Massachusetts By Thomas S. Kidd Cotton Mather’s calendar had just rolled over to January 1, 1723, and with the turn he wrote his friend Robert Wodrow of Scotland concerning frightening though unsurprising news: “The Indians of the East, under the Fascinations of a French Priest, and Instigations of our French Neighbours, have begun a New War upon us…”1 Though they had enjoyed a respite from actual war since the Peace of Utrecht postponed hostilities between the French and British in 1713, New Englanders always knew that it was only a matter of time before the aggressive interests, uncertain borders, and conflicting visions of the religious contest between them and the French Canadians would lead to more bloodshed. -

The Beginning of Winchester on Massachusett Land

Posted at www.winchester.us/480/Winchester-History-Online THE BEGINNING OF WINCHESTER ON MASSACHUSETT LAND By Ellen Knight1 ENGLISH SETTLEMENT BEGINS The land on which the town of Winchester was built was once SECTIONS populated by members of the Massachusett tribe. The first Europeans to interact with the indigenous people in the New Settlement Begins England area were some traders, trappers, fishermen, and Terminology explorers. But once the English merchant companies decided to The Sachem Nanepashemet establish permanent settlements in the early 17th century, Sagamore John - English Puritans who believed the land belonged to their king Wonohaquaham and held a charter from that king empowering them to colonize The Squaw Sachem began arriving to establish the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Local Tradition Sagamore George - For a short time, natives and colonists shared the land. The two Wenepoykin peoples were allies, perhaps uneasy and suspicious, but they Visits to Winchester were people who learned from and helped each other. There Memorials & Relics were kindnesses on both sides, but there were also animosities and acts of violence. Ultimately, since the English leaders wanted to take over the land, co- existence failed. Many sachems (the native leaders), including the chief of what became Winchester, deeded land to the Europeans and their people were forced to leave. Whether they understood the impact of their deeds or not, it is to the sachems of the Massachusetts Bay that Winchester owes its beginning as a colonized community and subsequent town. What follows is a review of written documentation KEY EVENTS IN EARLY pertinent to the cultural interaction and the land ENGLISH COLONIZATION transfers as they pertain to Winchester, with a particular focus on the native leaders, the sachems, and how they 1620 Pilgrims land at Plymouth have been remembered in local history. -

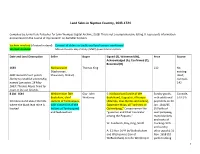

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country.Pdf

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country, 1643-1724 Compiled by Jenny Hale Pulsipher for John Wompas Digital Archive, 2018. This is not a comprehensive listing. It represents information encountered in the course of my research on Swindler Sachem. Sachem involved (if noted in deed) Consent of elders or traditional land owners mentioned Woman involved Massachusetts Bay Colony (MBC) government actions Date and Land Description Seller Buyer Signed (S), Witnessed (W), Price Source Acknowledged (A), ConFirmed (C), Recorded (R) 1643 Nashacowam Thomas King £12 No [Nashoonan, existing MBC General Court grants Shawanon, Sholan] deed; liberty to establish a township, Connole, named Lancaster, 18 May 142 1653; Thomas Noyes hired by town to lay out bounds. 8 Oct. 1644 Webomscom [We Gov. John S: Nodowahunt [uncle of We Sundry goods, Connole, Bucksham, chief Winthrop Bucksham], Itaguatiis, Alhumpis with additional 143-145 10 miles round about the hills sachem of Tantiusques, [Allumps, alias Hyems and James], payments on 20 where the black lead mine is with consent of all the Sagamore Moas, all “sachems of Jan. 1644/45 located Indians at Tantiusques] Quinnebaug,” Cassacinamon the (10 belts of and Nodowahunt “governor and Chief Councelor wampampeeg, among the Pequots.” many blankets and coats of W: Sundanch, Day, King, Smith trucking cloth and sundry A: 11 Nov. 1644 by WeBucksham other goods); 16 and Washcomos (son of Nov. 1658 (10 WeBucksham) to John Winthrop Jr. yards trucking 1 cloth); 1 March C: 20 Jan. 1644/45 by Washcomos 1658/59 to Amos Richardson, agent for John Winthrop Jr. (JWJr); 16 Nov. 1658 by Washcomos to JWJr.; 1 March 1658/59 by Washcomos to JWJr 22 May 1650 Connole, 149; MD, MBC General Court grants 7:194- 3200 acres in the vicinity of 195; MCR, LaKe Quinsigamond to Thomas 4:2:111- Dudley, esq of Boston and 112 Increase Nowell of Charleston [see 6 May and 28 July 1657, 18 April 1664, 9 June 1665].