Mn (II) Oxidation in Pseudomonas Putida GB-1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplementary Table S1. Table 1. List of Bacterial Strains Used in This Study Suppl

Supplementary Material Supplementary Tables: Supplementary Table S1. Table 1. List of bacterial strains used in this study Supplementary Table S2. List of plasmids used in this study Supplementary Table 3. List of primers used for mutagenesis of P. intermedia Supplementary Table 4. List of primers used for qRT-PCR analysis in P. intermedia Supplementary Table 5. List of the most highly upregulated genes in P. intermedia OxyR mutant Supplementary Table 6. List of the most highly downregulated genes in P. intermedia OxyR mutant Supplementary Table 7. List of the most highly upregulated genes in P. intermedia grown in iron-deplete conditions Supplementary Table 8. List of the most highly downregulated genes in P. intermedia grown in iron-deplete conditions Supplementary Figures: Supplementary Figure 1. Comparison of the genomic loci encoding OxyR in Prevotella species. Supplementary Figure 2. Distribution of SOD and glutathione peroxidase genes within the genus Prevotella. Supplementary Table S1. Bacterial strains Strain Description Source or reference P. intermedia V3147 Wild type OMA14 isolated from the (1) periodontal pocket of a Japanese patient with periodontitis V3203 OMA14 PIOMA14_I_0073(oxyR)::ermF This study E. coli XL-1 Blue Host strain for cloning Stratagene S17-1 RP-4-2-Tc::Mu aph::Tn7 recA, Smr (2) 1 Supplementary Table S2. Plasmids Plasmid Relevant property Source or reference pUC118 Takara pBSSK pNDR-Dual Clonetech pTCB Apr Tcr, E. coli-Bacteroides shuttle vector (3) plasmid pKD954 Contains the Porpyromonas gulae catalase (4) -

Progress Toward Understanding the Contribution of Alkali Generation in Dental Biofilms to Inhibition of Dental Caries

International Journal of Oral Science (2012) 4, 135–140 ß 2012 WCSS. All rights reserved 1674-2818/12 www.nature.com/ijos REVIEW Progress toward understanding the contribution of alkali generation in dental biofilms to inhibition of dental caries Ya-Ling Liu1, Marcelle Nascimento2 and Robert A Burne1 Alkali production by oral bacteria is believed to have a major impact on oral microbial ecology and to be inibitory to the initiation and progression of dental caries. A substantial body of evidence is beginning to accumulate that indicates the modulation of the alkalinogenic potential of dental biofilms may be a promising strategy for caries control. This brief review highlights recent progress toward understanding molecular genetic and physiologic aspects of important alkali-generating pathways in oral bacteria, and the role of alkali production in the ecology of dental biofilms in health and disease. International Journal of Oral Science (2012) 4, 135–140; doi:10.1038/ijos.2012.54; published online 21 September 2012 Keywords: arginine; biofilm; dental caries; microbial ecology; urea INTRODUCTION via the arginine deiminase system (ADS).15–18 Urea is provided con- Dental biofilms, the microbial communities that colonize the surfaces tinuously in salivary secretions and gingival exudates at concentra- of the teeth, exist in a dynamic equilibrium with host defenses and are tions roughly equivalent to those in serum, which range from about 3 generally compatible with the integrity of the tissues they colonize.1–4 to10 mmol?L21 in healthy humans. Urea is rapidly converted to A strong correlation is evident between the compositional and meta- ammonia and CO2 by bacterial ureases (Figure 1), which are produced bolic changes of the dental biofilms and the transition from oral health by a small subset of oral bacteria that includes Streptococcus salivarius, 2,5 to disease states, including dental caries and periodontal disease. -

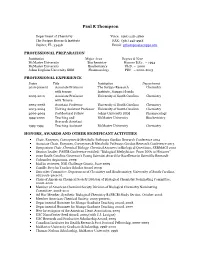

Paul R Thompson

Paul R Thompson Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Pharmacology Voice: (508) 856-8492 UMass Medical School FAX: (508) 856-6215 Worcester, MA, 01605 Email: [email protected] PROFESSIONAL PREPARATION Institution Major Area Degree & Year McMaster University Biochemistry Honors B.S.c. – 1994 McMaster University Biochemistry Ph.D. – 2000 Johns Hopkins University SOM Pharmacology PDF – 2000-2003 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Dates Title Institution Department 2014-present Professor and Director University of Massachusetts Biochemistry and of Chemical Biology Medical School Molecular with tenure Pharmacology 2010-2014 Associate Professor The Scripps Research Chemistry with tenure Institute, Scripps Florida 2009-2010 Associate Professor University of South Carolina Chemistry with Tenure 2004-2008 Assistant Professor University of South Carolina Chemistry 2003-2004 Visiting Assistant Professor University of South Carolina Chemistry 2000-2003 Postdoctoral Fellow Johns University SOM Pharmacology 1994-2000 Teaching and McMaster University Biochemistry Research Assistant 1993-1994 Teaching Assistant McMaster University Chemistry HONORS, AWARDS AND OTHER SIGNIFICANT ACTIVITIES • Consultant to Disarm Therapeutics, 2018 to present • Chair, Bioorganic Chemistry Gordon Research Conference 2017 • Permanent Member, Synthetic Biological Chemistry B (SBCB) Study Section, NIH October 2016- present. • Consultant to Celgene, 2018 to present. • Associate Chair, Bioorganic Chemistry Gordon Research Conference 2017 • Consultant to Bristol Myers Squibb, -

Paul R Thompson

Paul R Thompson Department of Chemistry Voice: (561) 228-2860 The Scripps Research Institute FAX: (561) 228-2918 Jupiter, FL, 33458 Email: [email protected] PROFESSIONAL PREPARATION Institution Major Area Degree & Year McMaster University Biochemistry Honors B.S.c. – 1994 McMaster University Biochemistry Ph.D. – 2000 Johns Hopkins University SOM Pharmacology PDF – 2000-2003 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Dates Title Institution Department 2010-present Associate Professor The Scripps Research Chemistry with tenure Institute, Scripps Florida 2009-2010 Associate Professor University of South Carolina Chemistry with Tenure 2004-2008 Assistant Professor University of South Carolina Chemistry 2003-2004 Visiting Assistant Professor University of South Carolina Chemistry 2000-2003 Postdoctoral Fellow Johns University SOM Pharmacology 1994-2000 Teaching and McMaster University Biochemistry Research Assistant 1993-1994 Teaching Assistant McMaster University Chemistry HONORS, AWARDS AND OTHER SIGNIFICANT ACTIVITIES Chair, Enzymes, Coenzymes & Metabolic Pathways Gordon Research Conference 2014 Associate Chair, Enzymes, Coenzymes & Metabolic Pathways Gordon Research Conference 2013 Symposium Chair, Chemical Biology: Chemical Answers to Biological Questions, SERMACS 2012 Session Leader, FASEB Conference entitled: "Biological Methylation: From DNA to Histones" 2010 South Carolina Governor’s Young Scientist Award for Excellence in Scientific Research Cofounder Arginomix, 2009 Mail in reviewer, NIH Challenge Grants, June 2009 Camille Dreyfus Teacher Scholar -

The Microbiota-Produced N-Formyl Peptide Fmlf Promotes Obesity-Induced Glucose

Page 1 of 230 Diabetes Title: The microbiota-produced N-formyl peptide fMLF promotes obesity-induced glucose intolerance Joshua Wollam1, Matthew Riopel1, Yong-Jiang Xu1,2, Andrew M. F. Johnson1, Jachelle M. Ofrecio1, Wei Ying1, Dalila El Ouarrat1, Luisa S. Chan3, Andrew W. Han3, Nadir A. Mahmood3, Caitlin N. Ryan3, Yun Sok Lee1, Jeramie D. Watrous1,2, Mahendra D. Chordia4, Dongfeng Pan4, Mohit Jain1,2, Jerrold M. Olefsky1 * Affiliations: 1 Division of Endocrinology & Metabolism, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA. 2 Department of Pharmacology, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA. 3 Second Genome, Inc., South San Francisco, California, USA. 4 Department of Radiology and Medical Imaging, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA. * Correspondence to: 858-534-2230, [email protected] Word Count: 4749 Figures: 6 Supplemental Figures: 11 Supplemental Tables: 5 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online April 22, 2019 Diabetes Page 2 of 230 ABSTRACT The composition of the gastrointestinal (GI) microbiota and associated metabolites changes dramatically with diet and the development of obesity. Although many correlations have been described, specific mechanistic links between these changes and glucose homeostasis remain to be defined. Here we show that blood and intestinal levels of the microbiota-produced N-formyl peptide, formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLF), are elevated in high fat diet (HFD)- induced obese mice. Genetic or pharmacological inhibition of the N-formyl peptide receptor Fpr1 leads to increased insulin levels and improved glucose tolerance, dependent upon glucagon- like peptide-1 (GLP-1). Obese Fpr1-knockout (Fpr1-KO) mice also display an altered microbiome, exemplifying the dynamic relationship between host metabolism and microbiota. -

Q 297 Suppl USE

The following supplement accompanies the article Atlantic salmon raised with diets low in long-chain polyunsaturated n-3 fatty acids in freshwater have a Mycoplasma dominated gut microbiota at sea Yang Jin, Inga Leena Angell, Simen Rød Sandve, Lars Gustav Snipen, Yngvar Olsen, Knut Rudi* *Corresponding author: [email protected] Aquaculture Environment Interactions 11: 31–39 (2019) Table S1. Composition of high- and low LC-PUFA diets. Stage Fresh water Sea water Feed type High LC-PUFA Low LC-PUFA Fish oil Initial fish weight (g) 0.2 0.4 1 5 15 30 50 0.2 0.4 1 5 15 30 50 80 200 Feed size (mm) 0.6 0.9 1.3 1.7 2.2 2.8 3.5 0.6 0.9 1.3 1.7 2.2 2.8 3.5 3.5 4.9 North Atlantic fishmeal (%) 41 40 40 40 40 30 30 41 40 40 40 40 30 30 35 25 Plant meals (%) 46 45 45 42 40 49 48 46 45 45 42 40 49 48 39 46 Additives (%) 3.3 3.2 3.2 3.5 3.3 3.4 3.9 3.3 3.2 3.2 3.5 3.3 3.4 3.9 2.6 3.3 North Atlantic fish oil (%) 9.9 12 12 15 16 17 18 0 0 0 0 0 1.2 1.2 23 26 Linseed oil (%) 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 6.8 8.1 8.1 9.7 11 10 11 0 0 Palm oil (%) 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 3.2 3.8 3.8 5.4 5.9 5.8 5.9 0 0 Protein (%) 56 55 55 51 49 47 47 56 55 55 51 49 47 47 44 41 Fat (%) 16 18 18 21 22 22 22 16 18 18 21 22 22 22 28 31 EPA+DHA (% diet) 2.2 2.4 2.4 2.9 3.1 3.1 3.1 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 4 4.2 Table S2. -

Occurrence of Agmatine Pathway for Putrescine Synthesis in Selenomonas Ruminatium

Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem., 72 (2), 445–455, 2008 Occurrence of Agmatine Pathway for Putrescine Synthesis in Selenomonas ruminatium Shaofu LIAO,1;* Phuntip POONPAIROJ,1;** Kyong-Cheol KO,1;*** Yumiko TAKATUSKA,1;**** y Yoshihiro YAMAGUCHI,1;***** Naoki ABE,1 Jun KANEKO,1 and Yoshiyuki KAMIO2; 1Laboratory of Applied Microbiology, Department of Microbial Biotechnology, Graduate School of Agricultural Science, Tohoku University, 1-1 Amamiyamachi, Aobaku, Sendai 981-8555, Japan 2Department of Human Health and Nutrition, Graduate School of Comprehensive Human Sciences, Shokei Gakuin University, 4-10-1 Yurigaoka, Natori 981-1295, Japan Received August 28, 2007; Accepted November 16, 2007; Online Publication, February 7, 2008 [doi:10.1271/bbb.70550] Selenomonas ruminantium synthesizes cadaverine and Polyamines such as putrescine, cadaverine, and putrescine from L-lysine and L-ornithine as the essential spermidine are essential constituents of peptidoglycan constituents of its peptidoglycan by a constitutive lysine/ and they play a significant role in the maintenance of the ornithine decarboxylase (LDC/ODC). S. ruminantium integrity of the cell envelope in Selenomonas ruminan- grew normally in the presence of the specific inhibitor tium, Veillonella parvulla, V. alcalescens, and Anaero- for LDC/ODC, DL- -difluoromethylornithine, when vibrio lipolytica.1–3) When S. ruminantium and two arginine was supplied in the medium. In this study, species of Veillonella are grown in a medium supple- we discovered the presence of arginine decarboxylase mented with putrescine or cadaverine, putrescine and (ADC), the key enzyme in agmatine pathway for cadaverine respectively link covalently to the -carbox- putrescine synthesis, in S. ruminantium. We purified yl group of the D-glutamic acid residue of the peptido- and characterized ADC and cloned its gene (adc) from glycan, which is catalyzed by diamine:lipid intermediate S. -

12) United States Patent (10

US007635572B2 (12) UnitedO States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,635,572 B2 Zhou et al. (45) Date of Patent: Dec. 22, 2009 (54) METHODS FOR CONDUCTING ASSAYS FOR 5,506,121 A 4/1996 Skerra et al. ENZYME ACTIVITY ON PROTEIN 5,510,270 A 4/1996 Fodor et al. MICROARRAYS 5,512,492 A 4/1996 Herron et al. 5,516,635 A 5/1996 Ekins et al. (75) Inventors: Fang X. Zhou, New Haven, CT (US); 5,532,128 A 7/1996 Eggers Barry Schweitzer, Cheshire, CT (US) 5,538,897 A 7/1996 Yates, III et al. s s 5,541,070 A 7/1996 Kauvar (73) Assignee: Life Technologies Corporation, .. S.E. al Carlsbad, CA (US) 5,585,069 A 12/1996 Zanzucchi et al. 5,585,639 A 12/1996 Dorsel et al. (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 5,593,838 A 1/1997 Zanzucchi et al. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 5,605,662 A 2f1997 Heller et al. U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. 5,620,850 A 4/1997 Bamdad et al. 5,624,711 A 4/1997 Sundberg et al. (21) Appl. No.: 10/865,431 5,627,369 A 5/1997 Vestal et al. 5,629,213 A 5/1997 Kornguth et al. (22) Filed: Jun. 9, 2004 (Continued) (65) Prior Publication Data FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS US 2005/O118665 A1 Jun. 2, 2005 EP 596421 10, 1993 EP 0619321 12/1994 (51) Int. Cl. EP O664452 7, 1995 CI2O 1/50 (2006.01) EP O818467 1, 1998 (52) U.S. -

Supplementary Figure 1. Rpod Sequence Alignment. Protein Sequence Alignment Was Performed for Rpod from Three Species, Pseudoruegeria Sp

J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.1911.11006 J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.2003.03025 Supplementary Figure 1. RpoD sequence alignment. Protein sequence alignment was performed for RpoD from three species, Pseudoruegeria sp. M32A2M (FPS10_24745, this study), Ruegeria pomeroyi (NCBI RefSeq: WP_011047484.1), and Escherichia coli (NCBI RefSeq: NP_417539.1). Multalin version 5.4.1 was used for the analysis. Subregion 2 and 4 are represented in a rectangle, and the helix-turn-helix motif in subregion 4 is highlighted in red. The amino acid degeneration from any of the three was highlighted in light gray and the sequence degeneration between Pseudoruegeria sp. M32A2M and R. pomeroyi is highlighted in dark gray. The substituted two amino acids into HTH motif (K578Q and D581S) against E. coli were marked as asterisk. Supplementary Table 1. Genome assembly statistics Categories Pseudoruegeria sp. M32A2M Number of scaffolds less than 1,000 bp 0 Number of scaffolds between 1,000 bp –10,000 bp 39 Number of scaffolds between 10,000 bp – 100,000 bp 38 Number of scaffolds larger than 100,000 bp 14 Number of scaffolds 91 Total assembled length (bp) 5,466,515 G+C contents (%) 62.4 N50 (bp) 249,384 Minimum length of scaffold (bp) 1,015 Maximum length of scaffold (bp) 733,566 Total Ns included in the draft genome 2,158 Supplementary Table 2. The list of gene annotation and its functional categorization in Pseudoruegeria sp. -

POLSKIE TOWARZYSTWO BIOCHEMICZNE Postępy Biochemii

POLSKIE TOWARZYSTWO BIOCHEMICZNE Postępy Biochemii http://rcin.org.pl WSKAZÓWKI DLA AUTORÓW Kwartalnik „Postępy Biochemii” publikuje artykuły monograficzne omawiające wąskie tematy, oraz artykuły przeglądowe referujące szersze zagadnienia z biochemii i nauk pokrewnych. Artykuły pierwszego typu winny w sposób syntetyczny omawiać wybrany temat na podstawie możliwie pełnego piśmiennictwa z kilku ostatnich lat, a artykuły drugiego typu na podstawie piśmiennictwa z ostatnich dwu lat. Objętość takich artykułów nie powinna przekraczać 25 stron maszynopisu (nie licząc ilustracji i piśmiennictwa). Kwartalnik publikuje także artykuły typu minireviews, do 10 stron maszynopisu, z dziedziny zainteresowań autora, opracowane na podstawie najnow szego piśmiennictwa, wystarczającego dla zilustrowania problemu. Ponadto kwartalnik publikuje krótkie noty, do 5 stron maszynopisu, informujące o nowych, interesujących osiągnięciach biochemii i nauk pokrewnych, oraz noty przybliżające historię badań w zakresie różnych dziedzin biochemii. Przekazanie artykułu do Redakcji jest równoznaczne z oświadczeniem, że nadesłana praca nie była i nie będzie publikowana w innym czasopiśmie, jeżeli zostanie ogłoszona w „Postępach Biochemii”. Autorzy artykułu odpowiadają za prawidłowość i ścisłość podanych informacji. Autorów obowiązuje korekta autorska. Koszty zmian tekstu w korekcie (poza poprawieniem błędów drukarskich) ponoszą autorzy. Artykuły honoruje się według obowiązujących stawek. Autorzy otrzymują bezpłatnie 25 odbitek swego artykułu; zamówienia na dodatkowe odbitki (płatne) należy zgłosić pisemnie odsyłając pracę po korekcie autorskiej. Redakcja prosi autorów o przestrzeganie następujących wskazówek: Forma maszynopisu: maszynopis pracy i wszelkie załączniki należy nadsyłać w dwu egzem plarzach. Maszynopis powinien być napisany jednostronnie, z podwójną interlinią, z marginesem ok. 4 cm po lewej i ok. 1 cm po prawej stronie; nie może zawierać więcej niż 60 znaków w jednym wierszu nie więcej niż 30 wierszy na stronie zgodnie z Normą Polską. -

Polyamines Mitigate Antibiotic Inhibition of A.Actinomycetemcomitans Growth

Polyamines Mitigate Antibiotic Inhibition of A.actinomycetemcomitans Growth THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Allan Wattimena Graduate Program in Dentistry The Ohio State University 2017 Master's Examination Committee: Dr John Walters, Advisor Dr Purnima Kumar Dr Sara Palmer Dr Shareef Dabdoub Copyright by Allan Wattimena 2017 Abstract Polyamines are ubiquitous polycationic molecules that are present in all prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. They are the breakdown products of amino acids and are important modulators of cell growth, stress and cell proliferation. Polyamines are present in higher concentrations in the periodontal pocket and may affect antibiotic resistance of bacterial biofilms. The effect of polyamines was investigated with amoxicillin (AMX), azithromycin (AZM) and doxycycline (DOX) on the growth of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (A.a.) Y4 strain. Bacteria were grown in brain heart infusion broth under the following conditions: 1) A.a. only, 2) A.a. + antibiotic, 3) A.a. + antibiotic + polyamine mix (1.4mM putrescine, 0.4mM spermidine, 0.4mM spermine). Growth curve analysis, MIC determination and metatranscriptomic analysis were carried out. The presence of exogenous polyamines produced a small, but significant increase in growth of A.a. Polyamines mitigated the inhibitory effect of AMX, AZM and DOX on A.a. growth. Metatranscriptomic analysis revealed differing transcriptomic profiles when comparing AMX and AZM in the presence of polyamines. Polyamines produced a transient mitigation of AMX inhibition, but did not have a significant effect on gene transcription. Many gene transcription changes were seen when polyamines were in the presence of AZM. -

Supplemental Figure S1. the Map of the JCVI-Syn1.0 Genome Showing

Supplemental Figure S1. The map of the JCVI-syn1.0 genome showing candidate non- essential genes uncovered in the current study (blue) and regions deleted in the seven- and eight-deletion strains (green). The deleted regions include restriction enzyme genes deleted in the JCVI-syn1.0 ∆1-6 genome. Supplemental Figure S2. Distribution of transposon-hit genes by functional category. The numbers of genes hit by transposons five times or more (“hit”) are shown in blue and those hit less than five times (“not hit”) are shown in red. Only disruptive transposon insertions (see Methods) are included in this analysis. Functional categories are based on a published study (Gibson et al., 2010). The category NULL includes 41 RNA genes and 19 non-conserved hypothetical protein genes. Notably, none of the RNA genes was hit five or more times by transposons (Supplemental Table S2). Supplemental Figure S3. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analysis of reduced genomes. (A) XhoI digest. The expected bands were 586 kb, 259 kb, and 217 kb for the starting strain (syn1.0 ∆1–6 strain), 533 kb, 231 kb, and 198 kb for the eight-cluster deletion strains, and 533 kb, 231 kb, and 210 kb for the seven-cluster deletion strains. The actual result was consistent with the expected result. (B) NaeI digest. The expected bands that would be visible in this analysis were 520 kb, 450 kb, 73 kb, and 18 kb for the starting strain, 446 kb, 424 kb, 73 kb, and 18 kb for the eight-cluster deletion strains, and 458 kb, 424 kb, 73 kb, and 18 kb for the seven-cluster deletion strains.