Meat and Ethics Off the Table: Food Labeling and the Role of Consumers As Agents of Food Systems Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Climate and Security Fellowship Program's “Risks Briefers,”

CLIMATE AND SECURITY FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM RISKS BRIEFERS SEPTEMBER 2019 Climate and Security Advisory Group, Climate and Security Fellowship Program | https://climateandsecurity.org/csagfellowship/ U.S. service members with Joint Task Force - Leeward Islands and members of the U.S. Agency for International Development’s Disaster Assistance Response Team unload supplies from a U.S. Army CH-47 Chinook helicopter at the port of Roseau, Dominica, Sept. 30, 2017. At the request of USAID, JTF-LI has deployed aircraft and service members to assist in delivering relief supplies to Dominica in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria. The task force is a U.S. military unit composed of Marines, Soldiers, Sailors and Airmen, and represents U.S. Southern Command’s primary response to the hurricanes that have affected the eastern Caribbean. U.S. MARINE CORPS / SGT. MELISSA MARTENS Climate and Security Advisory Group, Climate and Security Fellowship Program | https://climateandsecurity.org/csagfellowship/ 2 In response to increasing interest in career pathways for climate and security practitioners, the Climate and Security Advisory Group (CSAG) has developed a community-wide Climate Security Fellowship Program and is pleased to announce the 2018 class of CSAG Climate and Security Fellows. The CSAG Climate and Security Fellowship program is the first professional organization for emerging leaders seeking meaningful careers at the intersection of climate change and security. The program connects established climate security experts with prospective future leaders through a year-long mentorship program. CSAG Climate Security Fellows gain experience through research and writing, field trips and outings, and networking with experts and practitioners. Ultimately, fellows will play a leading role in expanding the climate and security network of the next generation and solving some of the most complex risks the world faces. -

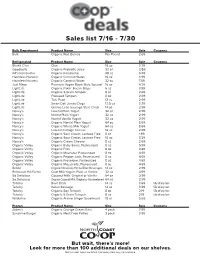

Sales List 7/16 - 7/30

Sales list 7/16 - 7/30 Bulk Department Product Name Size Sale Coupons Bulk Organic Red Quinoa Per Pound 2.69 Refrigerated Product Name Size Sale Coupons Bhakti Chai Chai 16 oz 3.39 Goodbelly Organic Probiotic Juice 32 oz 2/$5 GT’s Kombucha Organic Kombucha 48 oz 5.99 Harmless Harvest Organic Coconut Water 16 oz 3.99 Harmless Harvest Organic Coconut Water 32 oz 7.69 Just Mayo Premium Vegan Mayo-Style Spread 16 oz 4.39 LightLife Organic Fakin’ Bacon Strips 6 oz 3.99 LightLife Organic 3-Grain Tempeh 8 oz 2.69 LightLife Flaxseed Tempeh 8 oz 2.69 LightLife Tofu Pups 12 oz 2.99 LightLife Smart Deli Jumbo Dogs 13.5 oz 3.39 LightLife Gimme Lean Sausage Style Chub 14 oz 2.99 Nancy’s Low-fat Plain Yogurt 32 oz 2.99 Nancy’s Nonfat Plain Yogurt 32 oz 2.99 Nancy’s Nonfat Vanilla Yogurt 32 oz 2.99 Nancy’s Organic Nonfat Plain Yogurt 64 oz 8.69 Nancy’s Organic Whole Milk Yogurt 64 oz 8.69 Nancy’s Low-fat Cottage Cheese 16 oz 2.99 Nancy’s Organic Sour Cream, Lactose Free 8 oz 1.69 Nancy’s Organic Sour Cream, Lactose Free 16 oz 3.39 Nancy’s Organic Cream Cheese 8 oz 2.69 Organic Valley Organic Baby Swiss, Pasteurized 8 oz 5.99 Organic Valley Organic Feta 8 oz 4.69 Organic Valley Organic Muenster, Pasteurized 8 oz 4.69 Organic Valley Organic Pepper Jack, Pasteurized 8 oz 4.69 Organic Valley Organic Provolone, Pasteurized 8 oz 4.69 Organic Valley Organic Mozzarella, Pasteurized 8 oz 4.69 Rebbl Organic Non-Dairy Herbal Elixir Beverages 12 oz 2.99 Redwood Hill Farms Goat Milk Yogurt, Plain or Vanilla 32 oz 4.99 So Delicious Coconut Milk, Original or Vanilla -

Kosher Items Gold’S Horseradish Walnut Oils, Spray Oils, All Or Call 802-861-9700

Spreads, Oils, Aisles 2,4,6, Kosher Labels About City Market, Onion River Co-op Dressings & Condiments Cooler near Bakery Barney Butter Almond Butters Musette Mustards There are more than 1,000 kosher certifiying City Market, Onion River Co-op is a consumer Blake Hill Preserves Natural Value Mustards agencies around the world! That means there are a cooperative, with over 11,300 Members, selling Bonne Maman Fruit Preserves Nasoya Nayonaise Where Bragg’s Nutritional Yeast Nuco Liquid Coconut Oils lot of different certified kosher symbols. Here are wholesome food and other products while Bubbies Pickles Nutella Hazelnut Spread some of the ones we’ve noticed on products at City building a vibrant, empowered community and Cains Tartar Sauce Nutiva Coconut & Red Palm do I find...? Cedar’s Hummus Oils Market: a healthier world, all in a sustainable manner. Colavita Olive Oils Once Again Nut Butters & Located in downtown Burlington, Vermont, Dr. Bronner’s Coconut Oils Spreads Eden Mirin Rice Cooking Rabbi’s Roots Horseradish City Market provides a large selection of organic Wine, Sesame Oil, Vinegars ShurfineItalian & Ranch and conventional foods, and thousands of local Field Day Organic Canned Dressings Olives, Olive Oils, Peanut Smucker’s Preserves and Vermont-made products. Visit City Market, Butter Spectrum Oils Olive, Canola, Onion River Co-op online at Filippo Berio Olive Oils Sesame, Peanut, Almond & Kosher Items Gold’s Horseradish Walnut Oils, Spray Oils, All www.CityMarket.coop or call 802-861-9700. Gulden’s Mustards Mayos Hain Safflower -

OPTAVIA® Vegetarian Information Sheet

Vegetarian Information Sheet At OPTAVIA, we believe you can live the best life possible and we know that requires a healthy you. Whether you adopt a vegetarian diet for health, ecological, religious or ethical reasons, there are plenty of OPTAVIA Fuelings to fit into your lifestyle. In fact, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics has suggested that fortified foods like OPTAVIA Fuelings are a great choice for those looking to lose or maintain their weight and follow a vegetarian lifestyle.1 Designed to provide the right nutrition at every stage of the journey, our scientifically designed Fuelings are nutritious, delicious and effective. All OPTAVIA Essential Fuelings and OPTAVIA Select Fuelings are free from colors, flavors, and sweeteners from artificial sources, contain high quality, complete protein, probiotic cultures and 24 vitamins and minerals. OPTAVIA Fuelings are nutrient dense, portion controlled and nutritionally interchangeable. 1Academy of Nutrition & Dietetics position paper Volume 116, Number 12. Page 1970-1975 (December 2016) Vegetarian Options Do not contain eggs or milk: OPTAVIA Essential Oatmeal (all) OPTAVIA Essential Crunchy O’s (all) OPTAVIA Puffed Sweet & Salty Snacks* Medifast Classic Cereal Crunch (all) Flavor Infusers* (all) Crackers* (all) Olive Oil & Sea Salt Popcorn* Contain milk but not eggs: OPTAVIA Select and Essential Bars (all) OPTAVIA Select and Essential Mac & Cheese (all) OPTAVIA Select Hot Cereals (all) OPTAVIA Select Smoothies (all) OPTAVIA Essential Rustic Tomato Herb Penne OPTAVIA Essential Shakes -

➎Union Burger

for the long days and short years Welcome Guide Visiting? New to PDX? Your family’s ultimate Portland resource! Editor’s Note ............................................................................6 Find the Fun .............................................................................8 contents A helpful map to find many of the locations mentioned throughout the issue! Sponsored by OnPoint Credit Union. The Ultimate Portland Weekend With Kids ..................................................................................... 12 If you are new to Portland — or only vaguely remember exploring the city with your kids — this story is for you! Our long-weekend itinerary packs in the family fun. Plus the top smash-burger joints! By Denise Castañon. A Year of Fun .......................................................................22 Once upon a time, we went out to festivals and fairs and events perfect for kids and their grown-ups. Those days will be back, so here’s a reminder of the fun on the horizon! By Miranda Rake. The City Guide ...................................................................28 Take a deep dive into family-friendly neighborhoods across Portland’s quadrants and beyond. Find family-tested places to eat and play; housing costs; transit, walk and bike scores; and much more. PDX Trend: Fried Chicken Goodness .....................................41 The ultimate comfort food has taken over Portland. Find out where to get a crunchy-chicken fix. By Denise Castañon. GreatSchools.org: Ratings Aren’t the Whole Story -

PLANT-BASED MEAT: a HEALTHIER CHOICE? a Comprehensive Health and Nutrition Analysis of Plant-Based Meat Products in the Australian and New Zealand Markets

PLANT-BASED MEAT: A HEALTHIER CHOICE? A comprehensive health and nutrition analysis of plant-based meat products in the Australian and New Zealand markets Developed in collaboration with Teri Lichtenstein, Accredited Practising Dietitian Executive Summary 2 Executive Summary Purpose Structure Plant-based meat, as an increasingly popular category of meat Section I offers context on the historical evolution of meat that are energy dense and nutrient-poor; hyper-palatability alternatives across grocery and foodservice channels, has grown alternatives, who is eating them and the role they can play in leading to overconsumption, and; contribution to disruption of to reach critical mass in Australia and New Zealand. With people’s diets. This includes a categorical definition of plant- healthy meal patterns. countless new brands offering products across varied formats – based meats, as well as other meat alternatives, as a reference Section V explores research and innovations to improve from burgers and sausages to mince and poultry pieces – the for those new to the category. plant-based meats and address key ingredient and processing category has become established enough to begin attracting Section II reviews the health effects of the conventional meats concerns, as well as provides general guidance for manufacturers comparisons to conventional meat. for which plant-based meats, given their design as a centre-of- to further improve the health and nutrition of their products. This As with any fast-emerging food category that is often associated plate protein option, offer an alternative. This includes the section also offers guidance to consumers in determining the role with health, the wave of new plant-based meat products has association between high consumption of red meat (particularly of plant-based meats within their diet. -

Gluten-Free Products Shopping List

GLUTEN-FREE PRODUCTS SHOPPING LIST The items on this shopping list, to the best of our knowledge, are made without gluten or any ingredients derived from gluten-containing grains, such as wheat, barley, rye, spelt or kamut. It is possible that products labeled gluten-free may come into contact with gluten during manufacturing. However, with the current FDA guidelines, any product labeled gluten-free should have less than 20 parts per million (ppm), which is considered a safe amount for most individuals following a gluten-free diet. People who have celiac disease and individuals who are exquisitely sensitive may still have a reaction to foods with measurable, although tiny, amounts of gluten. In this case, it is helpful to find companies that produce products in a dedicated gluten-free facility or that are part of a certification program. Products with this symbol are certified by the Gluten-Free Certification Organization, and tested for less than 10 ppm. For more information visit their webpage at www.gfco.org. This list also indicates whether the gluten-free foods listed contain dairy, soy or egg in the ingredients. If soy lecithin is the source of soy in the product, (SL) will appear after the product description. Visit our website at www.newseasonsmarket.com for a list of our regularly scheduled complimentary gluten- free products store tours. Please direct questions and comments regarding this list to [email protected]. Disclaimer: This is merely a guide and we are unable to be responsible for individual reactions to any product. Please read each label carefully to determine whether a food is appropriate for you. -

Jumbo Dogs USA Specifications

Jumbo Dogs USA Specifications Item Number: 10354 Case GTIN: 100 25583 00658 1 Item UPC: 0 25583 00658 4 Net Weight: 14oz (397g) Case Pack: 6/14oz Microbiological Salmonella/Listeria: Negative Coliforms/E.Coli: <100CFU/g SPC, Yeast/Mold: <1000 CFU/g Chemical pH: 5.0-6.5 Aw: 0.93-0.98 Moisture: 45-55% Preserved Identity Vegan Non-GMO Certified Kosher Parve by KSA Low Saturated Fat No Cholesterol Excellent Source of Protein See nutrition information for sodium content INGREDIENTS: WATER, VITAL WHEAT GLUTEN, PEA PROTEIN, Handling EXPELLER PRESSED CANOLA OIL, ORGANIC TOFU (WATER, Keep Refrigerated ORGANIC SOYBEANS, MAGNESIUM CHLORIDE, CALCIUM Ready to Eat- Not Shelf Stable CHLORIDE), CONTAINS LESS THAN 2% OF CANE SUGAR, SEA SALT, SPICES, ONION POWDER, ANNATTO (FOR COLOR), NATUAL Shelf Life FLAVORS, NATURAL SMOKE FLAVOR, OAT FIBER, Frozen, unopened: n/a CARRAGEENAN, DEXTROSE, KONJAC, XANTHAN GUM. Refrigerated, unopened: 150 days from pack date CONTAINS: SOY, WHEAT Refrigerated, opened: 5-7 days Preparation Instructions: Grill: For 3-4 minutes, turning occasionally Microwave: On high, for 30 seconds. Stovetop: Saute in light oil until lightly browned, or boil in water for 90 seconds. Made with in Oregon Version: 190419 PO Box 176, Hood River, OR 97031 Revised by: NB Tofurky.com Reviewed by: MW Plant Based Original Sausage Beer Brat USA Specifications INGREDIENTS: WATER, VITAL WHEAT GLUTEN, EXPELLER PRESSED CANOLA OIL, ORGANIC TOFU (WATER, ORGANIC SOYBEANS, MAGNESIUM CHLORIDE, CALCIUM CHLORIDE), ONIONS, SOY FLOUR AND/OR CONCENTRATE, AMBER ALE (WATER, MALTED BARLEY, HOPS, YEAST), CONTAINS LESS THAN 2% OF SEA SALT, CANE SUGAR, SPICES, DEHYDRATED ONION, GRANULATED GARLIC, GARLIC PUREE, CARRAGEENAN, DEXTROSE, KONJAC, POTASSIUM CHLORIDE. -

Cheap and Easy Guide to an Earth-Friendly Diet

Cheap and Easy Guide to an Earth-friendly Diet So you’ve decided that you want to eat less meat: Smart choice! By reducing the amount of meat you eat, you’ll help protect endangered animals and the environment every day. If you’re not sure where to start or how to stick to your new diet on a budget, the Cheap & Easy Guide to an Earth-friendly Diet offers healthy, time-saving, wallet-friendly tips to help you accomplish your goal, whether you have your own kitchen or eat on campus. 10 Ways to Eat Earth-friendly Depending on where you eat out, you may find meatless options, or you may have to be more inventive to create meals out of what is available. If there is a microwave, Panini press or stir fry station, then you have an even greater ability to create your own meatless delicacies. Throughout this guide, meals that can easily be whipped up in a dining hall are indicated with an asterisk(*). 2. Sandwich 1. Every Meal Chart 3. Protein 4. Play Dress-up 5. Get Saucy 6. Be Prepared 7. Budget Wise 8. Eat Out 10. Meatless 9. Waste Less Motivation 1 1. Every Meal Matters: Every meatless meal helps protect wildlife and the environment. From breakfast to dinner (and all the snacks in between), it’s easy to eat less meat and more delicious plant-based foods. Breakfast: Oatmeal, bread (toast, bagel),* granola, dried fruit, cereal,* smoothies (add chia, hemp or flax for protein) or an acai bowl. Lunch: Sandwiches,* wraps* and pitas* (raw, toasted or Panini pressed) (see The Complete Sandwich Chart below), hearty soups (lentil, minestrone, black bean) or Ramen noodle bowls (the oriental and chili flavors of Top Ramen brand are vegan; add peanut butter and Sriracha to make “Pad Thai” Ramen). -

Public Goods for Cyberhealth

1 Cyberhealth and Informational Wellbeing By John Michael Thornton Darwin College April 2019 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2 3 Preface This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the relevant Degree Committee. 4 Abstract Title: Cyberhealth and Informational Wellbeing Author: John Michael Thornton In this dissertation, I present a new framework for conceptualizing the digital landscape inspired by the field of public health. I call this framework Public Cyberhealth. This framework is an alternative to the dominant cybersecurity paradigm, which frames cyberspace as a digital battleground. I argue that the philosophy of public health can be useful for thinking about the normative justification for—and ethical limits on—government intervention in cyberspace, while public health policy and institutions can serve as examples of how to manifest these higher principles (e.g. -

The Case for Public Investment in Alternative Proteins

THE CASE FOR PUBLIC INVESTMENT IN ALTERNATIVE PROTEINS BY ALEX SMITH, SALONI SHAH AND DAN BLAUSTEIN-REJTO EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report makes a comprehensive case for robust public investment in research and develop- ment for alternative proteins. It also provides a framework for how to spend these funds and maximize their benefit for reducing the environmental and health costs of meat consumption. Currently, the United States consumes more meat per capita than any other country in the world. The American diet’s emphasis on meat contributes to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, health problems, animal suffering, local pollution, and poor labor conditions. In the past decade, however, the U.S. has seen a burgeoning alternative meat industry, includ- ing cultivated products from companies like Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods, Mosa Meat, Memphis Meats, Blue Nalu, and Eat Just. Despite the industry’s growth, these products — still more expensive than conventional meat and lacking diversity — have yet to meaningfully reduce U.S. meat consumption. Alternative Meats Mitigate Externalities Related to Animal Agriculture With sufficient research and development (R&D) for new and improved products and produc- tion, the benefits for the environment, public health, and animal welfare could be enormous. The externalities from animal agriculture, such as GHG emissions and health impacts, cost the American public at least $388 billion per year. Replacing 45% of beef with plant-based alter- natives could, for example, reduce U.S. GHG emissions from agriculture by around one sixth. Substantial replacement would also reduce deaths associated with air pollution; overuse of antibiotics by livestock producers; and rates of colorectal cancer, heart disease and other diet- related issues. -

Tofurky Complaint

Case 3:20-cv-00674-BAJ-EWD Document 1 10/07/20 Page 1 of 17 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA ) TURTLE ISLAND FOODS SPC ) D/B/A TOFURKY COMPANY, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. ) MICHAEL G. STRAIN, in his official capacity as ) Commissioner of Agriculture and Forestry, ) ) Defendant. ) ) COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF 1. This is a civil-rights action challenging the constitutionality of Louisiana’s 2019 Act No. 273, codified at Louisiana Rev. Stat. §§ 3:4741–4746 (“Act 273” or “the Act”). 2. The Act imposes broad speech restrictions against food producers, prohibiting them from “[r]epresenting a food product as meat” if it is not derived from an animal carcass. It also prohibits food producers from using any language that “has been used or defined historically” in reference to certain state-favored “agricultural products,” including meat products. 3. The Act would prohibit the Plaintiff, Tofurky, from marketing or selling any of its products in Louisiana, including for example “plant-based burgers,” “plant-based ham style roast,” and “plant-based jumbo hot dogs.” If Tofurky continued to market or label its products in violation of the Act, the company would face civil penalties of $500 per violation per day. The Act is effective October 1, 2020. –1– Case 3:20-cv-00674-BAJ-EWD Document 1 10/07/20 Page 2 of 17 4. The Act imposes sweeping restrictions on commercial speech. It prohibits companies from sharing truthful and non-misleading information about their products while doing nothing to protect the public from any conceivable harm.