Italian Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fumarolic CO Output from Pico Do Fogo Volcano

Ital. J. Geosci., Vol. 139, No. 3 (2020), pp. 325-340, 9 figs., 3 tabs. (https://doi.org/10.3301/IJG.2020.03) © Società Geologica Italiana, Roma 2020 The fumarolic CO2 output from Pico do Fogo Volcano (Cape Verde) ALESSANDRO AIUPPA (1), MARCELLO BITETTO (1), ANDREA L. RIZZO (2), FATIMA VIVEIROS (3), PATRICK ALLARD (4), MARIA LUCE FREZZOTTI (5), VIRGINIA VALENTI (5) & VITTORIO ZANON (3, 4) ABSTRACT output started early back in the 1990s (e.g., GERLACH, 1991), The Pico do Fogo volcano, in the Cape Verde Archipelago off substantial budget refinements have only recently arisen the western coasts of Africa, has been the most active volcano in the from the 8-years (2011-2019) DECADE (Deep Earth Carbon Macaronesia region in the Central Atlantic, with at least 27 eruptions Degassing; https://deepcarboncycle.org/about-decade) during the last 500 years. Between eruptions fumarolic activity has research program of the Deep Carbon Observatory (https:// been persisting in its summit crater, but limited information exists for the chemistry and output of these gas emissions. Here, we use the deepcarbon.net/project/decade#Overview) (FISCHER, 2013; results acquired during a field survey in February 2019 to quantify FISCHER et alii, 2019). the quiescent summit fumaroles’ volatile output for the first time. By One key result of DECADE-funded research has been combining measurements of the fumarole compositions (using both a the recognition that the global CO2 output from subaerial portable Multi-GAS and direct sampling of the hottest fumarole) and volcanism is predominantly sourced from a relatively of the SO2 flux (using near-vent UV Camera recording), we quantify small number of strongly degassing volcanoes. -

The Domed Temple in Renaissance Italy and in Early Printed Sources

CHAPTER EIGHT THE DOMED TEMPLE IN RENAISSANCE ITALY AND IN EARLY PRINTED SOURCES During the Italian Renaissance the motif of the circular or octagonal Temple of Solomon took on a life of its own, for it became linked to the idea of a centralized church plan. Such a circular plan with its uniformity and har- mony came to connote the justice of God. Architects of the period ranked round and domical temples above all others, often spurred on, additionally, by their admiration for classical Roman architecture such as the Pantheon.1 In this climate, evoking Solomon’s Temple as a circular building was per- fectly natural, even though it contradicted the biblical text and the rectilin- ear measurements supposedly handed down by God.2 One of the first Renaissance paintings to include a circular Temple is Perugino’s “Delivery of the Keys to St. Peter” in the Sistine Chapel, dating from 1481. (fig. 8.1) Perugino executed the painting under the patronage of Sixtus IV, the pope responsible for the remodeling of the old Capella Magna into the new Sistine Chapel. The architecture and the mural paintings were planned simultaneously in the 1470s and were developed to emphasize the primacy of Rome and the papacy. The Perugino image reflects precisely that theme. In a wide piazza in front of the Temple, Christ gives the keys of temporal and spiritual power to the kneeling Peter. The Gospel passage referenced is Jesus’ pronouncement that he will hand over the keys of heaven to Peter (Matthew 16:18–20). Though Matthew’s Gospel records Jesus’ words, the text does not relate the actual handover—that had to be imagined. -

Regional Oral History Off Ice University of California the Bancroft Library Berkeley, California

Regional Oral History Off ice University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Richard B. Gump COMPOSER, ARTIST, AND PRESIDENT OF GUMP'S, SAN FRANCISCO An Interview Conducted by Suzanne B. Riess in 1987 Copyright @ 1989 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West,and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between the University of California and Richard B. Gump dated 7 March 1988. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Discovering the Lost Race Story: Writing Science Fiction, Writing Temporality

Discovering the Lost Race Story: Writing Science Fiction, Writing Temporality This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia 2008 Karen Peta Hall Bachelor of Arts (Honours) Discipline of English and Cultural Studies School of Social and Cultural Studies ii Abstract Genres are constituted, implicitly and explicitly, through their construction of the past. Genres continually reconstitute themselves, as authors, producers and, most importantly, readers situate texts in relation to one another; each text implies a reader who will locate the text on a spectrum of previously developed generic characteristics. Though science fiction appears to be a genre concerned with the future, I argue that the persistent presence of lost race stories – where the contemporary world and groups of people thought to exist only in the past intersect – in science fiction demonstrates that the past is crucial in the operation of the genre. By tracing the origins and evolution of the lost race story from late nineteenth-century novels through the early twentieth-century American pulp science fiction magazines to novel-length narratives, and narrative series, at the end of the twentieth century, this thesis shows how the consistent presence, and varied uses, of lost race stories in science fiction complicates previous critical narratives of the history and definitions of science fiction. In examining the implicit and explicit aspects of temporality and genre, this thesis works through close readings of exemplar texts as well as historicist, structural and theoretically informed readings. It focuses particularly on women writers, thus extending previous accounts of women’s participation in science fiction and demonstrating that gender inflects constructions of authority, genre and temporality. -

Janson. History of Art. Chapter 16: The

16_CH16_P556-589.qxp 12/10/09 09:16 Page 556 16_CH16_P556-589.qxp 12/10/09 09:16 Page 557 CHAPTER 16 CHAPTER The High Renaissance in Italy, 1495 1520 OOKINGBACKATTHEARTISTSOFTHEFIFTEENTHCENTURY , THE artist and art historian Giorgio Vasari wrote in 1550, Truly great was the advancement conferred on the arts of architecture, painting, and L sculpture by those excellent masters. From Vasari s perspective, the earlier generation had provided the groundwork that enabled sixteenth-century artists to surpass the age of the ancients. Later artists and critics agreed Leonardo, Bramante, Michelangelo, Raphael, Giorgione, and with Vasari s judgment that the artists who worked in the decades Titian were all sought after in early sixteenth-century Italy, and just before and after 1500 attained a perfection in their art worthy the two who lived beyond 1520, Michelangelo and Titian, were of admiration and emulation. internationally celebrated during their lifetimes. This fame was For Vasari, the artists of this generation were paragons of their part of a wholesale change in the status of artists that had been profession. Following Vasari, artists and art teachers of subse- occurring gradually during the course of the fifteenth century and quent centuries have used the works of this 25-year period which gained strength with these artists. Despite the qualities of between 1495 and 1520, known as the High Renaissance, as a their births, or the differences in their styles and personalities, benchmark against which to measure their own. Yet the idea of a these artists were given the respect due to intellectuals and High Renaissance presupposes that it follows something humanists. -

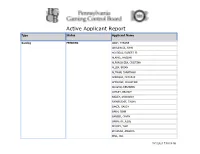

Active Applicant Report Type Status Applicant Name

Active Applicant Report Type Status Applicant Name Gaming PENDING ABAH, TYRONE ABULENCIA, JOHN AGUDELO, ROBERT JR ALAMRI, HASSAN ALFONSO-ZEA, CRISTINA ALLEN, BRIAN ALTMAN, JONATHAN AMBROSE, DEZARAE AMOROSE, CHRISTINE ARROYO, BENJAMIN ASHLEY, BRANDY BAILEY, SHANAKAY BAINBRIDGE, TASHA BAKER, GAUDY BANH, JOHN BARBER, GAVIN BARRETO, JESSE BECKEY, TORI BEHANNA, AMANDA BELL, JILL 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING BENEDICT, FREDRIC BERNSTEIN, KENNETH BIELAK, BETHANY BIRON, WILLIAM BOHANNON, JOSEPH BOLLEN, JUSTIN BORDEWICZ, TIMOTHY BRADDOCK, ALEX BRADLEY, BRANDON BRATETICH, JASON BRATTON, TERENCE BRAUNING, RICK BREEN, MICHELLE BRIGNONI, KARLI BROOKS, KRISTIAN BROWN, LANCE BROZEK, MICHAEL BRUNN, STEVEN BUCHANAN, DARRELL BUCKLEY, FRANCIS BUCKNER, DARLENE BURNHAM, CHAD BUTLER, MALKAI 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING BYRD, AARON CABONILAS, ANGELINA CADE, ROBERT JR CAMPBELL, TAPAENGA CANO, LUIS CARABALLO, EMELISA CARDILLO, THOMAS CARLIN, LUKE CARRILLO OLIVA, GERBERTH CEDENO, ALBERTO CENTAURI, RANDALL CHAPMAN, ERIC CHARLES, PHILIP CHARLTON, MALIK CHOATE, JAMES CHURCH, CHRISTOPHER CLARKE, CLAUDIO CLOWNEY, RAMEAN COLLINS, ARMONI CONKLIN, BARRY CONKLIN, QIANG CONNELL, SHAUN COPELAND, DAVID 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING COPSEY, RAYMOND CORREA, FAUSTINO JR COURSEY, MIAJA COX, ANTHONIE CROMWELL, GRETA CUAJUNO, GABRIEL CULLOM, JOANNA CUTHBERT, JENNIFER CYRIL, TWINKLE DALY, CADEJAH DASILVA, DENNIS DAUBERT, CANDACE DAVIES, JOEL JR DAVILA, KHADIJAH DAVIS, ROBERT DEES, I-QURAN DELPRETE, PAUL DENNIS, BRENDA DEPALMA, ANGELINA DERK, ERIC DEVER, BARBARA -

The Story of Architecture

A/ft CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY FINE ARTS LIBRARY CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 924 062 545 193 Production Note Cornell University Library pro- duced this volume to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. It was scanned using Xerox soft- ware and equipment at 600 dots per inch resolution and com- pressed prior to storage using CCITT Group 4 compression. The digital data were used to create Cornell's replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Stand- ard Z39. 48-1984. The production of this volume was supported in part by the Commission on Pres- ervation and Access and the Xerox Corporation. Digital file copy- right by Cornell University Library 1992. Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/cletails/cu31924062545193 o o I I < y 5 o < A. O u < 3 w s H > ua: S O Q J H HE STORY OF ARCHITECTURE: AN OUTLINE OF THE STYLES IN T ALL COUNTRIES • « « * BY CHARLES THOMPSON MATHEWS, M. A. FELLOW OF THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS AUTHOR OF THE RENAISSANCE UNDER THE VALOIS NEW YORK D. APPLETON AND COMPANY 1896 Copyright, 1896, By D. APPLETON AND COMPANY. INTRODUCTORY. Architecture, like philosophy, dates from the morning of the mind's history. Primitive man found Nature beautiful to look at, wet and uncomfortable to live in; a shelter became the first desideratum; and hence arose " the most useful of the fine arts, and the finest of the useful arts." Its history, however, does not begin until the thought of beauty had insinuated itself into the mind of the builder. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SE.Rtate. 5869

1910. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SE.rTATE. 5869 PETITIONS, ETC. Also, petition of Connecticut Fair Assoclation, fa>oring Honso bill 15422, the agricultural extension bill-to the Coil.lillittee on, Under clause 1 of Rule XXII, petitions and papers were laid Agriculture. on the Clerk's de k and referred us follows : By Mr. AlTDEHSOL T: l etition of D. A. Dewey, of Fostoria, Alm, petition ofJ. R.Dutton, of Colchester, Conn., for a parcels Ohio, for House bill 2223!:>-to the Committee on the Post-Office post bill-to the Committee on the Post-Office and Post-Roads. n.ncl Post-Road . Al o, petition of Connecticut State Association of Let!er C:ir Also, petition of William II. Gibson Post, No. 31, Department riers, fnyoring the pro rata bill and the Worcester classification of Ohio, Grnncl Army of tile Repul>llc, against statues being bill-to the Committee on the Post-Office and Po t-Roads. placctl in Statuary Hall that perpetuate memory of the southern By Mr. HOLLINGSWORTH : Paper to accompany bill for confeueracy-to the Committee on the Library. relief of Cicero Williams-to the Committee on Invalid Pensions. By Mr. HOWELL of Utah: Petition of Wasatch Lodge, .i.. To. Also, petition of Champion Grange, Patrons of Husband~·y, of Upper Sanclu k-y, Ohio, for Senate bill 6!)31, for an appropr1i;i. 370, of the Brotherhood of Railway Carmen of America, of tion of $WO,OOO for extension of work of the Office of Public Ogden, Utah, for granting leave of absence with pay to em Roads-to tlle Committee on Agriculture. -

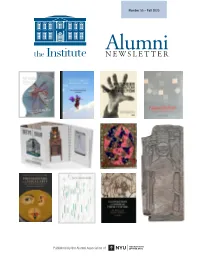

Institute of Fine Arts Alumni Newsletter, Number 55, Fall 2020

Number 55 – Fall 2020 NEWSLETTERAlumni PatriciaEichtnbaumKaretzky andZhangEr Neoclasicos rnE'-RTISTREINVENTiD,1~1-1= THEME""'lLC.IIEllMNICOLUCTION MoMA Ano M. Franco .. ..H .. •... 1 .1 e-i =~-:.~ CALLi RESPONSE Nyu THE INSTITUTE Published by the Alumni Association of II IOF FINE ARTS 1 Contents Letter from the Director In Memoriam ................. .10 The Year in Pictures: New Challenges, Renewed Commitments, Alumni at the Institute ..........16 and the Spirit of Community ........ .3 Iris Love, Trailblazing Archaeologist 10 Faculty Updates ...............17 Conversations with Alumni ....... .4 Leatrice Mendelsohn, Alumni Updates ...............22 The Best Way to Get Things Done: Expert on Italian Renaissance An Interview with Suzanne Deal Booth 4 Art Theory 11 Doctors of Philosophy Conferred in 2019-2020 .................34 The IFA as a Launching Pad for Seventy Nadia Tscherny, Years of Art-Historical Discovery: Expert in British Art 11 Master of Arts and An Interview with Jack Wasserman 6 Master of Science Dual-Degrees Dora Wiebenson, Conferred in 2019-2020 .........34 Zainab Bahrani Elected to the American Innovative, Infuential, and Academy of Arts and Sciences .... .8 Prolifc Architectural Historian 14 Masters Degrees Conferred in 2019-2020 .................34 Carolyn C Wilson Newmark, Noted Scholar of Venetian Art 15 Donors to the Institute, 2019-2020 .36 Institute of Fine Arts Alumni Association Offcers: Alumni Board Members: Walter S. Cook Lecture Susan Galassi, Co-Chair President Martha Dunkelman [email protected] and William Ambler [email protected] Katherine A. Schwab, Co-Chair [email protected] Matthew Israel [email protected] [email protected] Yvonne Elet Vice President Gabriella Perez Derek Moore Kathryn Calley Galitz [email protected] Debra Pincus [email protected] Debra Pincus Gertje Utley Treasurer [email protected] Newsletter Lisa Schermerhorn Rebecca Rushfeld Reva Wolf, Editor Lisa.Schermerhorn@ [email protected] [email protected] kressfoundation.org Katherine A. -

RAFFAELLO SANZIO Una Mostra Impossibile

RAFFAELLO SANZIO Una Mostra Impossibile «... non fu superato in nulla, e sembra radunare in sé tutte le buone qualità degli antichi». Così si esprime, a proposito di Raffaello Sanzio, G.P. Bellori – tra i più convinti ammiratori dell’artista nel ’600 –, un giudizio indicativo dell’incontrastata preminenza ormai riconosciuta al classicismo raffaellesco. Nato a Urbino (1483) da Giovanni Santi, Raffaello entra nella bottega di Pietro Perugino in anni imprecisati. L’intera produzione d’esordio è all’insegna di quell’incontro: basti osservare i frammenti della Pala di San Nicola da Tolentino (Città di Castello, 1500) o dell’Incoronazione di Maria (Città del Vaticano, Pinacoteca Vaticana, 1503). Due cartoni accreditano, ad avvio del ’500, il coinvolgimento nella decorazione della Libreria Piccolomini (Duomo di Siena). Lo Sposalizio della Vergine (Milano, Pinacoteca di Brera, 1504), per San Francesco a Città di Castello (Milano, Pinacoteca di Brera), segna un decisivo passo di avanzamento verso la definizione dello stile maturo del Sanzio. Il soggiorno a Firenze (1504-08) innesca un’accelerazione a tale processo, favorita dalla conoscenza dei tra- guardi di Leonardo e Michelangelo: lo attestano la serie di Madonne con il Bambino, i ritratti e le pale d’altare. Rimonta al 1508 il trasferimento a Roma, dove Raffaello è ingaggiato da Giulio II per adornarne l’appartamento nei Palazzi Vaticani. Nella prima Stanza (Segnatura) l’urbinate opera in autonomia, mentre nella seconda (Eliodoro) e, ancor più, nella terza (Incendio di Borgo) è affiancato da collaboratori, assoluti responsabili dell’ultima (Costantino). Il linguaggio raffaellesco, inglobando ora sollecitazioni da Michelangelo e dal mondo veneto, assume accenti rilevantissimi, grazie anche allo studio dell’arte antica. -

Peripheral Packwater Or Innovative Upland? Patterns of Franciscan Patronage in Renaissance Perugia, C.1390 - 1527

RADAR Research Archive and Digital Asset Repository Peripheral backwater or innovative upland?: patterns of Franciscan patronage in renaissance Perugia, c. 1390 - 1527 Beverley N. Lyle (2008) https://radar.brookes.ac.uk/radar/items/e2e5200e-c292-437d-a5d9-86d8ca901ae7/1/ Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, the full bibliographic details must be given as follows: Lyle, B N (2008) Peripheral backwater or innovative upland?: patterns of Franciscan patronage in renaissance Perugia, c. 1390 - 1527 PhD, Oxford Brookes University WWW.BROOKES.AC.UK/GO/RADAR Peripheral packwater or innovative upland? Patterns of Franciscan Patronage in Renaissance Perugia, c.1390 - 1527 Beverley Nicola Lyle Oxford Brookes University This work is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirelnents of Oxford Brookes University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. September 2008 1 CONTENTS Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 5 Preface 6 Chapter I: Introduction 8 Chapter 2: The Dominance of Foreign Artists (1390-c.1460) 40 Chapter 3: The Emergence of the Local School (c.1450-c.1480) 88 Chapter 4: The Supremacy of Local Painters (c.1475-c.1500) 144 Chapter 5: The Perugino Effect (1500-c.1527) 197 Chapter 6: Conclusion 245 Bibliography 256 Appendix I: i) List of Illustrations 275 ii) Illustrations 278 Appendix 2: Transcribed Documents 353 2 Abstract In 1400, Perugia had little home-grown artistic talent and relied upon foreign painters to provide its major altarpieces. -

Renaissance at the Vatican

Mensile Data Novembre 2013 Sotheby’s Pagina 46-47 Foglio 1 / 3 ART WORLD INSIDER Renaissance at the vatican VI (reigned 1963 to 1978), who knew many artists from his time in Paris, inaugurated the collection of modern art in the Borgia Apartments, decorated in the 15th century by Pinturicchio and home to some 600 donated works of variable quality (ironically, the Vatican’s version of Bacon’s famous popes is not among the best). Now, the Vatican is once again engaging with work by living artists and this year, for the fi rst time, it has a national pavilion at the Venice Biennale with commissioned works by the Italian multimedia collective Studio Azzurro, the Czech photographer Josef Koudelka and the American painter Lawrence Carroll. What do you say to these who think the Church should sell all of its treasures and give it to the poor? If it sold all its masterpieces, the poor would be poorer. Everything that is here is for the people of the world. Has the election of Pope Francis made a difference? PROFESSOR ANTONIO PAOLUCCI, DIRECTOR, VATICAN MUSEUMS Because of him, even more people have come to Rome. After the Angelus prayer and the papal audiences, they want to see the museums. We have 5.1 Anna Somers Cocks profi les Professor Antonio million visitors a year and I would like to have zero Paolucci, the custodian of one of the world’s growth now. greatest repositories of art at the Vatican Museums in Rome What is the role of the Vatican Museums? People expect them to be very pious: instead, you see After a brilliant career as a museum director in more male and female nudes than in most museums.