New Jersey's Washington Rocks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ's State Parks and Forest

Allamuchy Mountain, Stephens State Park Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ’s State Parks and Forest Prepared by Access NJ Contents Photo Credit: Matt Carlardo www.climbnj.com June, 2006 CRI 2007 Access NJ Scope of Inventory I. Climbing Overview of New Jersey Introduction NJ’s Climbing Resource II. Rock-Climbing and Cragging: New Jersey Demographics NJ's Climbing Season Climbers and the Environment Tradition of Rock Climbing on the East Coast III. Climbing Resource Inventory C.R.I. Matrix of NJ State Lands Climbing Areas IV. Climbing Management Issues Awareness and Issues Bolts and Fixed Anchors Natural Resource Protection V. Appendix Types of Rock-Climbing (Definitions) Climbing Injury Patterns and Injury Epidemiology Protecting Raptor Sites at Climbing Areas Position Paper 003: Climbers Impact Climbers Warning Statement VI. End-Sheets NJ State Parks Adopt a Crag 2 www.climbnj.com CRI 2007 Access NJ Introduction In a State known for its beaches, meadowlands and malls, rock climbing is a well established year-round, outdoor, all weather recreational activity. Rock Climbing “cragging” (A rock-climbers' term for a cliff or group of cliffs, in any location, which is or may be suitable for climbing) in NJ is limited by access. Climbing access in NJ is constrained by topography, weather, the environment and other variables. Climbing encounters access issues . with private landowners, municipalities, State and Federal Governments, watershed authorities and other landowners and managers of the States natural resources. The motives and impacts of climbers are not distinct from hikers, bikers, nor others who use NJ's open space areas. Climbers like these others, seek urban escape, nature appreciation, wildlife observation, exercise and a variety of other enriching outcomes when we use the resources of the New Jersey’s State Parks and Forests (Steve Matous, Access Fund Director, March 2004). -

EXPLORE OUR Historic Sites

EXPLORE LOCAL HISTORY Held annually on the third weekend in October, “Four Centuries in a Weekend” is a county-wide event showcasing historic sites in Union County. More than thirty sites are open to the public, featuring Where New Jersey History Began tours, exhibits and special events — all free of charge. For more information about Four Centuries, EXPLORE OUR Union County’s History Card Collection, and National Parks Crossroads of the American Historic Sites Revolution NHA stamps, go to www.ucnj.org/4C DEPARTMENT OF PARKS & RECREATION Office of Cultural & Heritage Affairs 633 Pearl Street, Elizabeth, NJ 07202 908-558-2550 • NJ Relay 711 [email protected] | www.ucnj.org/cultural Funded in part by the New Jersey Historical Commission, a division of the Department of State Union County A Service of the Union County Board of 08/19 Chosen Freeholders MAP center BERKELEY HEIGHTS Deserted Village of Feltville / Glenside Park 6 Littell-Lord Farmstead 7 CLARK Dr. William Robinson Plantation-Museum 8 CRANFORD Crane-Phillips House Museum 9 William Miller Sperry Observatory 10 ELIZABETH Boxwood Hall State Historic Site 11 Elizabeth Public Library 12 First Presbyterian Church / Snyder Academy 13 Nathaniel Bonnell Homestead & Belcher-Ogden Mansion 14 St. John’s Parsonage 15 FANWOOD Historic Fanwood Train Station Museum 16 GARWOOD 17 HILLSIDE Evergreen Cemetery 18 Woodruff House/Eaton Store Museum 19 The Union County Office of Cultural and Heritage KENILWORTH Affairs offers presentations to local organizations Oswald J. Nitschke House 20 at no charge, so your members can learn about: LINDEN 21 County history in general MOUNTAINSIDE Black history Deacon Andrew Hetfield House 22 NEW PROVIDENCE Women’s history Salt Box Museum 23 Invention, Innovation & Industry PLAINFIELD To learn more or to schedule a presentation, Drake House Museum 24 duCret School of Art 25 contact the History Programs Coordinator Plainfield Meetinghouse 26 at 908-436-2912 or [email protected]. -

In This Issue Upcoming Events Revolutionary War Battles in June

Official Publication of the WA State, Alexander Hamilton Chapter, SAR Volume V, Issue 6 (June 2019) Editor Dick Motz In This Issue Upcoming Events Revolutionary War Battles in June .................. 2 Alexander Hamilton Trivia? ............................ 2 Message from the President ........................... 2 What is the SAR? ............................................ 3 Reminders ..................................................... 3 Do you Fly? .................................................... 3 June Birthdays ............................................... 4 Northern Region Meeting Activities & Highlights ....................... 4 Chapter Web Site ........................................... 5 20 July: West Seattle Parade Member Directory Update ............................. 5 Location: West Seattle (Map Link). Wanted/For Sale ............................................ 6 Southern Region Battles of the Revolutionary War Map ............ 6 4 July: Independence Day Parade Location: Steilacoom (Map Link). Plan ahead for these Special Dates in July 17 Aug: Woodinville Parade 4 Jul: Independence Day Location: Woodinville (Map Link) 6 Jul: International Kissing Day 6 Jul: National fried Chicken Day 2 Sep: Labor Day Parade (pending) 17 Jul: National Tattoo Day Location: Black Diamond (Map Link) 29 Jul: National Chicken Wing Day 15-16 Sep: WA State Fair Booth Location: Puyallup 21 Sep: Chapter meeting Johnny’s at Fife, 9:00 AM. 9 Nov: Veterans Day Parade Location: Auburn (Map Link) 14 Dec: Wreaths Across America Location: JBLM (Map -

Past Historic Preservation Awards

PAST SOMERSET COUNTY HISTORIC PRESERVATION AND HISTORY AWARDS PROGRAM RECIPIENTS 1993 HISTORIC PRESERVATION Adaptive Use Franklin Inn Used Book Store, Franklin Adaptive Use Leadership John Matyola, Bridgewater Franklin Inn Education & Leadership The Historical Society of Somerset Hills, Bernards 1994 HISTORIC PRESERVATION Preservation/Restoration Bachman-Wilson House, Millstone Lawrence & Sharon Tarantino Mount Bethel Meeting House, Warren Township Township of Warren The Brick Academy, Bernards Historical Society of the Somerset Hills Brick Academy Education “Live Historians” - Montgomery High School, Montgomery 1995 HISTORIC PRESERVATION Preservation/ Restoration Frelinghuysen- Elmendorf House, Hillsborough Nicholas and Deborah Petrock Frelinghuysen-Elmendorf House 1996 HISTORIC PRESERVATION Preservation/Restoration The Kirch-Ford House, Warren Township Township of Warren Hilltop, Hillsborough William and Karen Munro Somerset County Historic Courthouse, Somerville County of Somerset J. Harper Smith House- Somerville Mr. & Mrs. Thompson Mitchell Gomes Residence, North Plainfield Frank and Paula Gomes Continuing Use Bound Brook Diner, Bound Brook Chris Elik J. Harper Smith House Adaptive Use Springdale United Methodist Church Property, Warren Springdale United Methodist Church Neshanic Station, Branchburg John J. Higgins Education Hillsborough, an Architectural History Township of Hillsborough 1997 HISTORIC PRESERVATION Preservation/Restoration Staats/Van Doren House, Montgomery Richard Meyer Adaptive Use Basking Ridge Old Fire House, Bernards -

LEAGUE NEWS the Newsletter of the League of Historical Societies of New Jersey

LEAGUE NEWS The Newsletter of the League of Historical Societies of New Jersey Vol. 43 No. 3 www.lhsnj.org August 2018 Sunday, October 28, 2018 Here are the winners for the Fall Meeting 2017 Kevin M. Hale Annual Publications Awards Jewish Historical Society of Metrowest, Whippany, Morris County Historic Tours st ************************* 1 place: “A Weekend in Old Monmouth First Weekend in May” Article, registration form, and produced by the Monmouth County Historical Commission. directions, p. 19-20 2nd place: “The Pathways of History Week- end Tour 2017” produced by 19 Historic groups in Morris County. 3rd place: “Historic Tour of Woodbridge, Volume IX Edgar Hill and Sur- rounds: The Ties That Bind” produced by the Woodbridge Township Historic Preservation Commission. Newsletters 1st place: “Old Baldy Civil War Roundtable” produced by the Old Baldy Civil War Roundtable of Philadelphia. 2nd place: “Ocean’s Heritage” produced by the Township of Ocean Historical Museum. 3rd place: “South River Historical & Preservation News” produced by the South River Historical & Preservation Society, Inc. SAVE THESE DATES FOR UPCOMING LEAGUE MEETINGS Sunday, October 28, 2018—Jewish Historical Society of New Jersey, Whippany, Morris County April 6, 2019—Ocean County Historical Society, Toms River, Ocean County June 1, 2019—Dey Farm, Monroe Township, Middlesex County Fall 2019—Lake Hopatcong Historical Museum, Landing, Roxbury Township, Morris County Winter 2020—Camden County Historical Society/Camden County History Alliance, Camden County Spring 2020—Red Mill Museum Village, Clinton, Hunterdon County We encourage your society to host a future League meeting. If you would like this opportunity to showcase your site, just contact Linda Barth, 908-240-0488, [email protected], and she will put you in touch with the regional vice-president for your area. -

Federal Register/Vol. 67, No. 76/Friday, April 19, 2002/Notices

19430 Federal Register / Vol. 67, No. 76 / Friday, April 19, 2002 / Notices 2002, Public Law 107–258. It is measures that would not prevent postponed. The public will be notified anticipated that the proposed non- damages from a reoccurrence of a storm of the forthcoming public hearing date, structural alternatives for flood event similar to the 1999 Hurricane location and time, as well as the protection in Segment A and Segment N Floyd storm. comment period expiration date. Any of the project will provide benefits to The local sponsors for the Green comments received in the meantime the environmental quality of the Brook Flood Control Project also will be made a part of the administrative floodplain in the area and reduce requested that three commercial record and will be considered in the adverse impacts of the project to properties, along Raritan Avenue and Final Environmental Impact Statement. forested wetland and upland habitat. Lincoln Boulevard, that were proposed FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Public comments on the EA will assist to be protected by a proposed levee/ Teresa (Hughes) Spagna, U.S. Army in the Corps’ evaluation of the project floodwall as described in the Corps’ Corps of Engineers, Huntington District, modification and will be reflected in the 1997 recommended NED plan, be Attn: Regulatory Branch–OR–FS, 502 final EA. bought out as part of the project plan. 8th Street, Huntington, West Virginia DATES: The draft EA will be available for Ten other properties along Raritan 25701, telephone (304) 529–5710 or public review from April 22, 2002 Avenue, that were proposed to be electronic mail at through May 22, 2002. -

NJS: an Interdisciplinary Journal Winter 2017 107

NJS: An Interdisciplinary Journal Winter 2017 107 Hills, Huts, and Horse-Teams: The New Jersey Environment and Continental Army Winter Encampments, 1778-1780 By Steven Elliott DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14713/njs.v3i1.67 New Jersey’s role as a base for the Continental Army during the War of Independence has played an important part in the state’s understanding of its role in the American Revolution, and continues to shape the state’s image as the “Cockpit of the Revolution,” and “Crossroads of the American Revolution” today. This article uncovers how and why the Continental Army decided to place the bulk of its forces in northern New Jersey for two consecutive winters during the war. Unlike the more renowned Valley Forge winter quarters, neither New Jersey encampment has received significant scholarly attention, and most works that have covered the topic have presumed the state’s terrain offered obvious strategic advantages for an army on the defensive. This article offers a new interpretation, emphasizing the army’s logistical needs including forage for its animals and timber supplies for constructing winter shelters. The availability of these resources, rather than easily defended rough terrain or close-proximity to friendly civilians, led Washington and his staff to make northern New Jersey its mountain home for much of the war. By highlighting to role of the environment in shaping military strategy, this article adds to our understanding of New Jersey’s crucial role in the American struggle for independence. Introduction In early December, 1778, patriot soldiers from Delaware, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia arrived at the southern foothills of New Jersey’s Watchung Mountains and began erecting a log-hut winter encampment near Middlebrook. -

Water Resources of the New Jersey Part of the Ramapo River Basin

Water Resources of the New Jersey Part of the Ramapo River Basin GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1974 Prepared in cooperation with the New Jersey Department of Conservation and Economic Development, Division of Water Policy and Supply Water Resources of the New Jersey Part of the Ramapo River Basin By JOHN VECCHIOLI and E. G. MILLER GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1974 Prepared in cooperation with the New Jersey Department of Conservation and Economic Development, Division of Water Policy and Supply UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1973 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 72-600358 For sale bv the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $2.20 Stock Number 2401-02417 CONTENTS Page Abstract.................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction............................................................................................ ............ 2 Purpose and scope of report.............................................................. 2 Acknowledgments.......................................................................................... 3 Previous studies............................................................................................. 3 Geography...................................................................................................... 4 Geology -

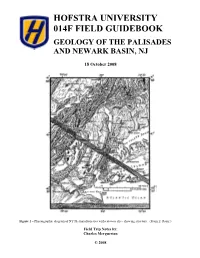

Hofstra University 014F Field Guidebook Geology of the Palisades and Newark Basin, Nj

HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY 014F FIELD GUIDEBOOK GEOLOGY OF THE PALISADES AND NEWARK BASIN, NJ 18 October 2008 Figure 1 – Physiographic diagram of NY Metropolitan area with cutaway slice showing structure. (From E. Raisz.) Field Trip Notes by: Charles Merguerian © 2008 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS..................................................................................................................................... i INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 GEOLOGIC BACKGROUND....................................................................................................... 4 PHYSIOGRAPHIC SETTING................................................................................................... 4 BEDROCK UNITS..................................................................................................................... 7 Layers I and II: Pre-Newark Complex of Paleozoic- and Older Rocks.................................. 8 Layer V: Newark Strata and the Palisades Intrusive Sheet.................................................. 12 General Geologic Relationships ....................................................................................... 12 Stratigraphic Relationships ............................................................................................... 13 Paleogeographic Relationships ......................................................................................... 16 Some Relationships Between Water and Sediment......................................................... -

JAMES DOUGHERTY Revolutionary War Soldier

JAMES DOUGHERTY Revolutionary War Soldier By David M. Dougherty Copyright 2009 All Rights Reserved !2 Contents 1. Genealogy and Background - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4 2. Service in the Continental Army - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 10 3. The Quebec Expedition - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 14 4. The Battle for Quebec - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 27 5. A Prisoner of the British - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 35 6. Back in the Continental Army - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 39 7. Battle of Brandywine - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 43 8. Battle of Germantown - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 46 9. Valley Forge. Commander-in-Chief’s Guard - - - - 48 10. Battle of Monmouth Courthouse - - - - - - - - - - - - 52 11. Operations Around New York City - - - - - - - - - - - 56 12. Detached Service in Pennsylvania - - - - - - - - - - - - 57 13. Back With the Guard - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 59 14. Civilian Life After the War - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 63 Genealogy Chart - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 66 Documents - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 68 Notes - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 77 Select Bibliography - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 81 !3 !4 1. Genealogy and Background James Dougherty was born in Antrim, either the town or county or both, Ulster Region, Ireland, on December 25, 1749. He immigrated to Pennsylvania shortly before the outbreak of the Revolutionary war, fought -

Military History Anniversaries 16 Thru 30 June

Military History Anniversaries 16 thru 30 June Events in History over the next 15 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Jun 16 1832 – Native Americans: Battle of Burr Oak Grove » The Battle is either of two minor battles, or skirmishes, fought during the Black Hawk War in U.S. state of Illinois, in present-day Stephenson County at and near Kellogg's Grove. In the first skirmish, also known as the Battle of Burr Oak Grove, on 16 JUN, Illinois militia forces fought against a band of at least 80 Native Americans. During the battle three militia men under the command of Adam W. Snyder were killed in action. The second battle occurred nine days later when a larger Sauk and Fox band, under the command of Black Hawk, attacked Major John Dement's detachment and killed five militia men. The second battle is known for playing a role in Abraham Lincoln's short career in the Illinois militia. He was part of a relief company sent to the grove on 26 JUN and he helped bury the dead. He made a statement about the incident years later which was recollected in Carl Sandburg's writing, among others. Sources conflict about who actually won the battle; it has been called a "rout" for both sides. The battle was the last on Illinois soil during the Black Hawk War. Jun 16 1861 – Civil War: Battle of Secessionville » A Union attempt to capture Charleston, South Carolina, is thwarted when the Confederates turn back an attack at Secessionville, just south of the city on James Island. -

Lower Devonian Glacial Erratics from High Mountain, Northern New Jersey, USA: Discovery, Provenance, and Significance

Lower Devonian glacial erratics from High Mountain, northern New Jersey, USA: Discovery, provenance, and significance Martin A. Becker1*and Alex Bartholomew2 1. Department of Environmental Science, William Paterson University, Wayne, New Jersey 07470, USA 2. Geology Department, SUNY, New Paltz, New York 12561, USA *Corresponding author <[email protected]> Date received 31 January 2013 ¶ Date accepted 22 November 2013 ABSTRACT Large, fossiliferous, arenaceous limestone glacial erratics are widespread on High Mountain, Passaic County, New Jersey. Analysis of the invertebrate fossils along with the distinct lithology indicates that these erratics belong to the Rickard Hill Facies of the Schoharie Formation (Lower Devonian, Tristates Group). Outcrops of the Rickard Hill Facies of the Schoharie Formation occur in a narrow belt within the Helderberg Mountains Region of New York due north of High Mountain. Reconstruction of the glacial history across the Helderberg Mountains Region and New Jersey Piedmont indicates that the Rickard Hill Erratics were transported tens of kilometers from their original source region during the late Wisconsinan glaciation. The Rickard Hill Erratics provide a unique opportunity to reconstruct an additional element of the complex surficial geology of the New Jersey Piedmont and High Mountain. Palynology of kettle ponds adjacent to High Mountain along with cosmogenic-nuclide exposure studies on glacial erratics from the late Wisconsinan terminal moraine and the regional lake varve record indicate that the final deposition of the Rickard Hill Erratics occurred within a few thousand years after 18 500 YBP. RÉSUMÉ Les grand blocs erratiques fossilifères apparaissent disperses dans les formations basaltiques de Preakness (Jurassique Inférieur) sur le mont High, dans le conte de Passaïc, dans l’État du New Jersey (NJ).