Environmental Resource Inventory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEW JERSEY History GUIDE

NEW JERSEY HISTOry GUIDE THE INSIDER'S GUIDE TO NEW JERSEY'S HiSTORIC SitES CONTENTS CONNECT WITH NEW JERSEY Photo: Battle of Trenton Reenactment/Chase Heilman Photography Reenactment/Chase Heilman Trenton Battle of Photo: NEW JERSEY HISTORY CATEGORIES NEW JERSEY, ROOTED IN HISTORY From Colonial reenactments to Victorian architecture, scientific breakthroughs to WWI Museums 2 monuments, New Jersey brings U.S. history to life. It is the “Crossroads of the American Revolution,” Revolutionary War 6 home of the nation’s oldest continuously Military History 10 operating lighthouse and the birthplace of the motion picture. New Jersey even hosted the Industrial Revolution 14 very first collegiate football game! (Final score: Rutgers 6, Princeton 4) Agriculture 19 Discover New Jersey’s fascinating history. This Multicultural Heritage 22 handbook sorts the state’s historically significant people, places and events into eight categories. Historic Homes & Mansions 25 You’ll find that historic landmarks, homes, Lighthouses 29 monuments, lighthouses and other points of interest are listed within the category they best represent. For more information about each attraction, such DISCLAIMER: Any listing in this publication does not constitute an official as hours of operation, please call the telephone endorsement by the State of New Jersey or the Division of Travel and Tourism. numbers provided, or check the listed websites. Cover Photos: (Top) Battle of Monmouth Reenactment at Monmouth Battlefield State Park; (Bottom) Kingston Mill at the Delaware & Raritan Canal State Park 1-800-visitnj • www.visitnj.org 1 HUnterdon Art MUseUM Enjoy the unique mix of 19th-century architecture and 21st- century art. This arts center is housed in handsome stone structure that served as a grist mill for over a hundred years. -

Borough of Keansburg County of Monmouth, New Jersey

BOROUGH OF KEANSBURG COUNTY OF MONMOUTH, NEW JERSEY AUDIT REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2018 BOROUGH OF KEANSBURG COUNTY OF MONMOUTH, NEW JERSEY TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2018 Exhibit Page Independent Auditor's Report 1 Independent Auditor's Report on Internal Control Over Financial Reporting and on Compliance and Other Matters Based on an Audit of Financial Schedules Performed in Accordance with Government Auditing Standards 5 Financial Schedules Current Fund Statements of Assets, Liabilities, Reserves and Fund Balance - Regulatory Basis A 9 Statements of Operations and Changes in Fund Balance - Regulatory Basis A-1 11 Statement of Revenues - Regulatory Basis A-2 12 Statement of Expenditures - Regulatory Basis A-3 14 Trust Fund Statements of Assets, Liabilities, Reserves and Fund Balance - Regulatory Basis B 20 General Capital Fund Statements of Assets, Liabilities, Reserves and Fund Balance - Regulatory Basis C 21 Statement of Fund Balance - Regulatory Basis C-1 22 Water/Sewer Utility Fund Statements of Assets, Liabilities, Reserves and Fund Balance - Regulatory Basis D 23 Statements of Operations and Changes in Fund Balance – Regulatory Basis D-1 25 Statement of Fund Balance - Regulatory Basis D-2 26 Statement of Revenues - Regulatory Basis D-3 27 Statement of Expenditures - Regulatory Basis D-4 28 General Fixed Assets Account Group Statements of Assets, Liabilities, Reserves and Fund Balance - Regulatory Basis E 29 Notes to Financial Schedules 33 BOROUGH OF KEANSBURG COUNTY OF MONMOUTH, NEW JERSEY -

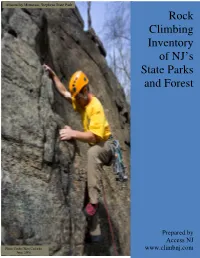

Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ's State Parks and Forest

Allamuchy Mountain, Stephens State Park Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ’s State Parks and Forest Prepared by Access NJ Contents Photo Credit: Matt Carlardo www.climbnj.com June, 2006 CRI 2007 Access NJ Scope of Inventory I. Climbing Overview of New Jersey Introduction NJ’s Climbing Resource II. Rock-Climbing and Cragging: New Jersey Demographics NJ's Climbing Season Climbers and the Environment Tradition of Rock Climbing on the East Coast III. Climbing Resource Inventory C.R.I. Matrix of NJ State Lands Climbing Areas IV. Climbing Management Issues Awareness and Issues Bolts and Fixed Anchors Natural Resource Protection V. Appendix Types of Rock-Climbing (Definitions) Climbing Injury Patterns and Injury Epidemiology Protecting Raptor Sites at Climbing Areas Position Paper 003: Climbers Impact Climbers Warning Statement VI. End-Sheets NJ State Parks Adopt a Crag 2 www.climbnj.com CRI 2007 Access NJ Introduction In a State known for its beaches, meadowlands and malls, rock climbing is a well established year-round, outdoor, all weather recreational activity. Rock Climbing “cragging” (A rock-climbers' term for a cliff or group of cliffs, in any location, which is or may be suitable for climbing) in NJ is limited by access. Climbing access in NJ is constrained by topography, weather, the environment and other variables. Climbing encounters access issues . with private landowners, municipalities, State and Federal Governments, watershed authorities and other landowners and managers of the States natural resources. The motives and impacts of climbers are not distinct from hikers, bikers, nor others who use NJ's open space areas. Climbers like these others, seek urban escape, nature appreciation, wildlife observation, exercise and a variety of other enriching outcomes when we use the resources of the New Jersey’s State Parks and Forests (Steve Matous, Access Fund Director, March 2004). -

EXPLORE OUR Historic Sites

EXPLORE LOCAL HISTORY Held annually on the third weekend in October, “Four Centuries in a Weekend” is a county-wide event showcasing historic sites in Union County. More than thirty sites are open to the public, featuring Where New Jersey History Began tours, exhibits and special events — all free of charge. For more information about Four Centuries, EXPLORE OUR Union County’s History Card Collection, and National Parks Crossroads of the American Historic Sites Revolution NHA stamps, go to www.ucnj.org/4C DEPARTMENT OF PARKS & RECREATION Office of Cultural & Heritage Affairs 633 Pearl Street, Elizabeth, NJ 07202 908-558-2550 • NJ Relay 711 [email protected] | www.ucnj.org/cultural Funded in part by the New Jersey Historical Commission, a division of the Department of State Union County A Service of the Union County Board of 08/19 Chosen Freeholders MAP center BERKELEY HEIGHTS Deserted Village of Feltville / Glenside Park 6 Littell-Lord Farmstead 7 CLARK Dr. William Robinson Plantation-Museum 8 CRANFORD Crane-Phillips House Museum 9 William Miller Sperry Observatory 10 ELIZABETH Boxwood Hall State Historic Site 11 Elizabeth Public Library 12 First Presbyterian Church / Snyder Academy 13 Nathaniel Bonnell Homestead & Belcher-Ogden Mansion 14 St. John’s Parsonage 15 FANWOOD Historic Fanwood Train Station Museum 16 GARWOOD 17 HILLSIDE Evergreen Cemetery 18 Woodruff House/Eaton Store Museum 19 The Union County Office of Cultural and Heritage KENILWORTH Affairs offers presentations to local organizations Oswald J. Nitschke House 20 at no charge, so your members can learn about: LINDEN 21 County history in general MOUNTAINSIDE Black history Deacon Andrew Hetfield House 22 NEW PROVIDENCE Women’s history Salt Box Museum 23 Invention, Innovation & Industry PLAINFIELD To learn more or to schedule a presentation, Drake House Museum 24 duCret School of Art 25 contact the History Programs Coordinator Plainfield Meetinghouse 26 at 908-436-2912 or [email protected]. -

Passaic River Navigation Update Outline

LOWER PASSAIC RIVER COMMERCIAL NAVIGATION ANALYSIS United States Army Corps of Engineers New York District Original: March, 2007 Revision 1: December, 2008 Revision 2: July, 2010 ® US Army Corps of Engineers LOWER PASSAIC RIVER RESTORATION PROJECT COMMERCIAL NAVIGATION ANALYSIS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Study Background and Authority…………………………………………………1 2.0 Study Purpose……………..………………………………………………………1 3.0 Location and Study Area Description……………………………………………..4 4.0 Navigation & Maintenance Dredging History…………………………………….5 5.0 Physical Constraints including Bridges…………………………………………...9 6.0 Operational Information………………………………………………………….11 6.1 Summary Data for Commodity Flow, Trips and Drafts (1980-2006)…..12 6.2 Berth-by-Berth Analysis (1997-2006)…………………………………...13 7.0 Conclusions………………………………………………………………………26 8.0 References………………………………………………………………………..29 LIST OF TABLES Table 1: Dredging History………………………………………………………………...6 Table 2. Bridges on the Lower Passaic River……………………………………………..9 Table 3. Channel Reaches and Active Berths of the Lower Passaic River………………18 Table 4: Most Active Berths, by Volume (tons) Transported on Lower Passaic River 1997-2006………………………………………………………………………..19 Table 5: Summary of Berth-by-Berth Analysis, below RM 2.0, 1997-2006.....................27 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1a. Federal Navigation Channel (RMs 0.0 – 8.0)………………………………….2 Figure 1b. Federal Navigation Channel (RMs 8.0 – 15.4)………………………………...3 Figure 2. Downstream View of Jackson Street Bridge and the City of Newark, May 2007………………………………………………………………………………..5 Figure 3. View Upstream to the Lincoln Highway Bridge and the Pulaski Skyway, May 2007………………………………………………………………………………..8 Figure 4. View Upstream to the Point-No-Point Conrail Bridge and the NJ Turnpike Bridge, May 2007……………………………………………………………......10 Figure 5. Commodities Transported, Lower Passaic River, 1997-2006…………………12 Figure 6. -

Board ~F Public Utility Commissioners

You Are Viewing an Archived Report from the New Jersey State Library EIGHTEENTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE Board ~f Public Utility Commissioners FOR THE ST A TE OF NEW JERSEY For the Year 1927 N.J. STATE LIBRARY P.O. BOX 520 rnENTON, NJ 08625--0520 MacCrellish & Quigley Co CPl'inters Trenton, New Jersey 1928 You Are Viewing an Archived Report from the New Jersey State Library • You Are Viewing an Archived Report from the New Jersey State Library REPORT To the Honorable A. Harry Moore, Governor of the State of New Jersey: Sm :-The Board of Public Utility Commissioners respectfully 'submits its report for the year 1927. During the year 580 cases have been formally disposed of. These have included adjustments of rates, formal complaints as to service, applications for approvals of privileges and franchises granted to public utilities by municipalities, elimination of grade crossings, issues of securities, leases and mergers of public utilities, sales of properties, disputes between electric companies as to territories to be served and proceedings involving proposed condemnation of land claimed to be necessary for the construction of power transmission lines. Formal hearings have been held on 172 days. An additional room has been added to the Board's quarters in Newark. This has been equipped for public hearings, and with the rooms previously available makes practicable con current hearings by the three members of the Board without interference with the work of the administrative force. In Trenton, by the courtesy of the State House Commission, court rooms are available for hearings. In addition to hearings in Trenton and Newark, the Board during the year has held hear ings in Jersey City, Camden, Phillipsburg, Bridgeton, Atlantic City, Toms River and Cape May Court House. -

Official Statement 2005 Second Sale

NEW ISSUE - BOOK-ENTRY ONLY RATINGS: Fitch: AAA Moody’s: Aaa Standard & Poor’s: AAA In the opinion of Gibbons, Del Deo, Dolan, Griffinger & Vecchione, a Professional Corporation, Bond Counsel to the County, assuming continuing compliance by the County with certain tax covenants described herein, under existing law, interest on the Series 2005 Bonds is excluded from the gross income of the owners of the Series 2005 Bonds for federal income tax purposes pursuant to Section 103 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended (the “Code”) and interest on the Series 2005 Bonds is not an item of tax preference under Section 57 of the Code for purposes of computing alternative minimum tax. In the case of certain corporate holders of the Series 2005 Bonds, interest on the Series 2005 Bonds will be included in the calculation of the alternative minimum tax as a result of the inclusion of interest on the Series 2005 Bonds in “adjusted current earnings” of certain corporations. See “TAX MATTERS” herein. ______________________ $30,000,000 COUNTY OF MONMOUTH New Jersey General Obligation Bonds, Series 2005 Dated: Date of Delivery Due: As shown below The $30,000,000 General Obligation Bonds, Series 2005 (the “Series 2005 Bonds”) will be issued by the County of Monmouth, New Jersey (the “County”) in fully registered form and, when issued, the Series 2005 Bonds will be registered in the name of Cede & Co., as nominee for The Depository Trust Company, New York, New York (“DTC”), an automated depository for securities and clearing house transactions, which will act as securities depository for the Series 2005 Bonds. -

Sussex County Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN for the County of Sussex “People and Nature Together” Compiled by Morris Land Conservancy with the Sussex County Open Space Committee September 30, 2003 County of Sussex Open Space and Recreation Plan produced by Morris Land Conservancy’s Partners for Greener Communities team: David Epstein, Executive Director Laura Szwak, Assistant Director Barbara Heskins Davis, Director of Municipal Programs Robert Sheffield, Planning Manager Tanya Nolte, Mapping Manager Sandy Urgo, Land Preservation Specialist Anne Bowman, Land Acquisition Administrator Holly Szoke, Communications Manager Letty Lisk, Office Manager Student Interns: Melissa Haupt Brian Henderson Brian Licinski Ken Sicknick Erin Siek Andrew Szwak Dolce Vieira OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN for County of Sussex “People and Nature Together” Compiled by: Morris Land Conservancy a nonprofit land trust with the County of Sussex Open Space Advisory Committee September 2003 County of Sussex Board of Chosen Freeholders Harold J. Wirths, Director Joann D’Angeli, Deputy Director Gary R. Chiusano, Member Glen Vetrano, Member Susan M. Zellman, Member County of Sussex Open Space Advisory Committee Austin Carew, Chairperson Glen Vetrano, Freeholder Liaison Ray Bonker Louis Cherepy Libby Herland William Hookway Tom Meyer Barbara Rosko Eric Snyder Donna Traylor Acknowledgements Morris Land Conservancy would like to acknowledge the following individuals and organizations for their help in providing information, guidance, research and mapping materials for the County of -

Passaic River Basin Re-Evaluation Study

History of Passaic Flooding Collaboration is Key Flooding has long been a problem in the In the past, the Corps of Engineers has Passaic River Basin. Since colonial times, partnered with the state of New Jersey m floods have claimed lives and damaged to study chronic flooding issues in the US Army Corps property. The growth of residential and Passaic River Basin but those studies of Engineers ® industrial development in recent years has have not resulted in construction of a multiplied the threat of serious damages comprehensive flood risk management and loss of life from flooding. More than solution. There have been many reasons 2.5 million people live in the basin (2000 for this, from discord between various census), and about 20,000 homes and governing bodies to real estate issues to places of business lie in the Passaic River environmental issues to cost concerns, floodplain. but the end result is always the same - a stalled project resulting in no solution. The most severe flood , the "flood of record ," occurred in 1903, and more recent floods We need a collaborative effort with in 1968, 1971 , 1972, 1973, two in 1975, complete support from local , state and 1984, 1992, 1999, 2005, 2007, 2010 and federal stakeholders.That means towns 2011 were sufficiently devastating to warrant within the basin that may have competing Federal Disaster declarations. interests must work together as partners. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has Public officials must understand the proposed flood risk management projects process, especially if a project is in the basin several times over the years, authorized for construction , is a long one including in 1939, 1948, 1962, 1969, 1972, and that as my colleague New Jersey 1973 and following the completion of the Department of Environmental Protection Corps' most recent study in the 1980s. -

126 Passaic River Basin 01387811 Ramapo River at Lenape Lane, at Oakland, Nj

126 PASSAIC RIVER BASIN 01387811 RAMAPO RIVER AT LENAPE LANE, AT OAKLAND, NJ LOCATION.--Lat 41°02'12", long 74°14'29", Bergen County, Hydrologic Unit 02030103, at bridge on Lenape Lane, 500 ft northwest of Crystal Lake, 0.7 mi north of Oakland, and 0.9 mi east of Ramapo Lake. DRAINAGE AREA.--135 mi2. PERIOD OF RECORD.--October 2004 to August 2005. REMARKS.--Total nitrogen (00600) equals the sum of dissolved ammonia plus organic nitrogen (00623), dissolved nitrite plus nitrate nitrogen (00631), and total particulate nitrogen (49570). COOPERATION.--Field data and samples for laboratory analyses were provided by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. Concentrations of ammonia in samples collected during November to December and August to September; orthophosphate in every sampling period except February to March; and nitrite, biochemical oxygen demand, total suspended residue, fecal coliform, E. coli, and enterococcus bacteria were determined by the New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services, Public Health and Environmental Laboratories, Environmental and Chemical Laboratory Services. COOPERATIVE NETWORK SITE DESCRIPTOR.--Statewide Status, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Watershed Management Area 3. WATER-QUALITY DATA, WATER YEAR OCTOBER 2004 TO SEPTEMBER 2005 Turbdty UV UV white absorb- absorb- Dis- pH, Specif. light, ance, ance, Baro- solved water, conduc- Hard- det ang 254 nm, 280 nm, metric Dis- oxygen, unfltrd tance, Temper- Temper- ness, Calcium 90+/-30 wat flt wat flt pres- solved percent field, wat unf ature, ature, water, water, corrctd units units sure, oxygen, of sat- std uS/cm air, water, mg/L as fltrd, Date Time NTRU /cm /cm mm Hg mg/L uration units 25 degC deg C deg C CaCO3 mg/L (63676) (50624) (61726) (00025) (00300) (00301) (00400) (00095) (00020) (00010) (00900) (00915) OCT 28.. -

Water Resources of the New Jersey Part of the Ramapo River Basin

Water Resources of the New Jersey Part of the Ramapo River Basin GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1974 Prepared in cooperation with the New Jersey Department of Conservation and Economic Development, Division of Water Policy and Supply Water Resources of the New Jersey Part of the Ramapo River Basin By JOHN VECCHIOLI and E. G. MILLER GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1974 Prepared in cooperation with the New Jersey Department of Conservation and Economic Development, Division of Water Policy and Supply UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1973 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 72-600358 For sale bv the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $2.20 Stock Number 2401-02417 CONTENTS Page Abstract.................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction............................................................................................ ............ 2 Purpose and scope of report.............................................................. 2 Acknowledgments.......................................................................................... 3 Previous studies............................................................................................. 3 Geography...................................................................................................... 4 Geology -

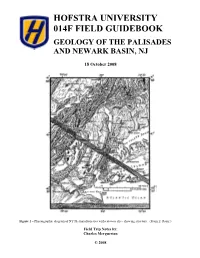

Hofstra University 014F Field Guidebook Geology of the Palisades and Newark Basin, Nj

HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY 014F FIELD GUIDEBOOK GEOLOGY OF THE PALISADES AND NEWARK BASIN, NJ 18 October 2008 Figure 1 – Physiographic diagram of NY Metropolitan area with cutaway slice showing structure. (From E. Raisz.) Field Trip Notes by: Charles Merguerian © 2008 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS..................................................................................................................................... i INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 GEOLOGIC BACKGROUND....................................................................................................... 4 PHYSIOGRAPHIC SETTING................................................................................................... 4 BEDROCK UNITS..................................................................................................................... 7 Layers I and II: Pre-Newark Complex of Paleozoic- and Older Rocks.................................. 8 Layer V: Newark Strata and the Palisades Intrusive Sheet.................................................. 12 General Geologic Relationships ....................................................................................... 12 Stratigraphic Relationships ............................................................................................... 13 Paleogeographic Relationships ......................................................................................... 16 Some Relationships Between Water and Sediment.........................................................