Striped Marlin Economic Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2016 SWFSC Billfish Newsletter

The SouthwestSWFSC Fisheries 2016 Billfish Science Newsletter Center’s 2016 Billfish Newsletter Global Tagging Map El Niño fishing conditions Catch-Photo-Release mobile phone application IGFA Great Marlin Race and satellite tagging 1 Top Anglers and Captains of 2015 SWFSC 2016 Billfish Newsletter Table of Contents Special Foreword …………………………………………………………….. 3 An Inside Look ……………………………………………………………..… 4 Prologue …………………………………………………………………….… 5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………..….… 5 The International Billfish Angler Survey ………………………………....... 7 Pacific blue marlin 9 Striped marlin 10 Indo-Pacific sailfish 11 Black marlin 13 Shortbill spearfish 13 Broadbill swordfish 14 The Billfish Tagging Program ……………………………………………..... 14 The Hawaiian Islands 16 2015 Tagging-at-a-Glance Map 17 Baja California and Guerrero, Mexico 18 Southern California 18 Western Pacific 18 Top Anglers and Captains Acknowledgements ……………………………. 19 Top Tagging Anglers 19 Top Tagging Captains 21 Tag Recoveries ……………………………………………………………….. 21 Science in Action: “The IGFA Great Marlin Race and Marlin Tagging” 23 Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………....... 25 Angler Photos ……………………………………………………………..….. 26 Congratulations to Captain Teddy Hoogs of the Bwana for winning this year’s cover photo contest! Teddy photographed this spectacular marlin off the coast of Hawaii. Fish on! 2 Special Forward James Wraith, director of the SWFSC Cooperative Billfish Tagging Program since 2007, recently left the SWFSC to move back to Australia. James was an integral part of the Highly Migratory Species (HMS) program. In addition to day-to-day work, James planned and organized the research cruises for HMS at the SWFSC and was involved in tagging thresher, blue, and mako sharks in the Southern California Bight for many years. We are sad to see him go but are excited for his future opportunities and thankful for his many contributions to the program over the last 10 years. -

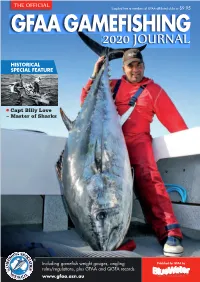

2020 Journal

THE OFFICIAL Supplied free to members of GFAA-affiliated clubs or $9.95 GFAA GAMEFISHING 2020 JOURNAL HISTORICAL THE OFFICIAL GAME FISHING ASSOCIATION OF AUSTRALIA 2020 JOURNAL THE OFFICIAL GAME FISHING ASSOCIATION SPECIAL FEATURE •Capt Billy Love – Master of Sharks Including gamefish weight gauges, angling Published for GFAA by rules/regulations, plus GFAA and QGFA records www.gfaa.asn.au LEGENDARY POWER COUPLE THE LEGEND CONTINUES, THE NEW TEREZ SERIES OF RODS BUILT ON SPIRAL-X AND HI-POWER X BLANKS ARE THE ULTIMATE SALTWATER ENFORCER. TECHNOLOGY 8000HG MODELS INFINITE POWER CAST 6’6” HEAVY 50-150lb SPIN JIG 5’10” MEDIUM 24kg CAST 6’6” X-HEAVY 65-200lb SPIN JIG 5’8” HEAVY 37kg THE STELLA SW REPRESENTS THE PINNACLE OF CAST 6’6” XX-HEAVY 80-200lb SPIN JIG 5’9” MEDIUM / HEAVY 24-37kg SHIMANO TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION IN THE CAST 7’0” MEDIUM 30-65lb OVERHEAD JIG 5’10” MEDIUM 24kg PURSUIT OF CREATING THE ULTIMATE SPINNING REEL. CAST 7’0” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb OVERHEAD JIG 5’8” HEAVY 37kg SPIN 6’9” MEDIUM 20-50lb SPIN 7’6” MEDIUM 10-15kg SPIN 6’9” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb SPIN 7’6” HEAVY 15-24kg TECHNOLOGY SPIN 6’9” HEAVY 50-100lb SPIN 7’0” MEDIUM 5-10kg SPIN 6’9” X-HEAVY 65-200lb SPIN 7’0” MEDIUM / LIGHT 8-12kg UPGRADED DRAG WITH SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM / LIGHT 15-40lb SPIN 7’9” STICKBAIT PE 3-8 HEAT RESISTANCE SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM lb20-50lb SPIN 8’0” GT PE 3-8 *10000 | 14000 models only SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb Check your local Shimano Stockists today. -

Flagstaff, Ash Fork, Grand Canyon, Page, Sedona, Seligman, Williams

ARIZONA TELEPHONE DIRECTORIES WHITE PAGES CITY: Flagstaff, Ash Fork, Grand Canyon, Page, Sedona, Seligman, Williams YEAR: July 1960 Flagstaf f • Ash Fork • Gran d Cany Rca an • Willia \ (if f*, ^fi Making the nation your neighborhood through the magic of • • • I R ECT I STANCE IALING This directory contains complete Direct Distance Dialing instructions. JULY 1960 MOUNTAIN STATES TELEPHONE Just because Do you really need a better reason to pick up your phone and enjoy a long distance call tonight? you like And here's a pleasant surprise . you can call station-to-station anywhere in the country after 6:00 PM or on Sunday and talk for three wonderful minutes to keep for $1.75 or less, plus tax. Even three-minute calls to Alaska or Hawaii are only $6.75 or less. in touch And remember, call by number—it's faster. Copyright 1960 by The Mountain States Telephone and Telegraph Company TELEPHONE DIRECTORY for FLAGSTAFF - ASH FORK - GRAND CANYON PAGE - SEDONA - SELIGMAN - WILLIAMS JULY 1960 TABLE OF CONTENTS ALPHABETICAL LISTINGS White Section FLAGSTAFF Page 11 ASH FORK Page 27 GRAND CANYON Page 28 PAGE Page 29 SEDONA. Page 31 SELIGMAN Page 33 WILLIAMS Page 34 CIVIC INFORMATION Blue Section CLASSIFIED SECTION Yellow Paget EMERGENCY CALLS — Fire, Police, Sheriff White Section, Page 3 GENERAL INFORMATION — Telephone Service White Section, Page 9 HOW TO PLACE TELEPHONE CALLS Out-of-Town Calls White Section, Page 5 Use of Dial Telephone White Section, Page 4 MAPS Blue Section TELEPHONE SERVICE CALLS White Section, Page 2 EMERGENCY CALLS Please determine the FIRE and POLICE departments which serve you and write their numbers in the spaces provided below. -

Analysis of Big Game Fishing Catches of Blue Marlin (Makaira Nigricans) in the Madeira Archipelago (Eastern Atlantic) and Factors That Affect Its Presence

sustainability Article Analysis of Big Game Fishing Catches of Blue Marlin (Makaira nigricans) in the Madeira Archipelago (Eastern Atlantic) and Factors that Affect Its Presence Roi Martinez-Escauriaza 1,* , Pablo Pita 2,3, Maria Lídia Ferreira de Gouveia 4, Nuno Manuel Abreu Gouveia 5, Eduardo Teixeira 6, Mafalda de Freitas 1,4,7,8 and Margarida Hermida 1,8 1 Oceanic Observatory of Madeira, Agência Regional para o Desenvolvimento da Investigação Tecnologia e Inovação (ARDITI), Edifício Madeira Tecnopolo, 9020-105 Funchal, Portugal; [email protected] 2 Campus Do Mar, International Campus of Excellence, 15782 Santiago de Compostela, Spain; [email protected] 3 Faculty of Political and Social Sciences, University of Santiago de Compostela, 15782 Santiago de Compostela, Spain 4 Direção Regional do Mar, Direção de Serviços de Monitorização, Estudos e Investigação do Mar (DRM/DSEIMar), 9004-562 Funchal, Portugal; [email protected] 5 Direção Regional de Pescas, Direção de Serviços de Inspeção e Controlo, Edifício da Sociedade Metropolitana de Câmara de Lobos, 9300-138 Câmara de Lobos, Portugal; [email protected] 6 Big Game Club of Portugal in Madeira, 9000-171 Funchal, Portugal; [email protected] 7 Estação de Biologia Marinha do Funchal, Cais do Carvão, 9000-003 Funchal, Portugal 8 MARE–Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre, Agência Regional para o Desenvolvimento da Investigação Tecnologia e Inovação (ARDITI), Edifício Madeira Tecnopolo, 9020-105 Funchal, Portugal; Citation: Martinez-Escauriaza, R.; [email protected] Pita, P.; de Gouveia, M.L.F.; Gouveia, * Correspondence: [email protected] N.M.A.; Teixeira, E.; de Freitas, M.; Hermida, M. -

2014 Pricing

2014 Pricing ITEM UPC SHORT DESCRIPTION COST RETAIL QTY ORD FISH RULERS Rulers for measuring fish FS50 724416999504 FISHSTICK-FLORIDA BOAT STICKER 3.50 6.99 FS50BB 724416025005 FISHSTICK-BOAT STICKER/BL BORD 3.50 6.99 FS51 724415050506 FISHSTICK-FLORIDA BOAT STICKER 3.50 6.99 FS98 724416010988 SALTY BONE FISH STICK- NO LAW 4.50 8.99 FS99 724416010995 SALTY BONE FISH STICK - LAWS 4.50 8.99 PROFILE STICKERS Our best selling full color designs measure 4.5" x 15" BPF2400 724416024008 MANTEE 3.00 5.99 BPF2400R 724416324009 REV MANATEE 3.00 5.99 BPF2476 724416002082 SNOOK 3.00 5.99 BPF2477 724416002068 REDFISH 3.00 5.99 BPF2478 724416002075 SAILFISH 3.00 5.99 BPF2479 724416024794 TARPON 3.00 5.99 BPF2480 724416002112 TUNA 3.00 5.99 BPF2481 724416324818 MARLIN 3.00 5.99 BPF2482 724416002013 LG MOUTH BASS 3.00 5.99 BPF2483 724416024831 WAHOO 3.00 5.99 BPF2484 724416002044 MAHI 3.00 5.99 BPF2498 724416024985 STRIPED BASS 3.00 5.99 BPF2501 724416002105 SPEC. TROUT 3.00 5.99 BPF2502 724416025029 COBIA 3.00 5.99 BPF2505 724416025050 SNAPPER 3.00 5.99 BPF2506 724416025067 POMPANO 3.00 5.99 BPF2507 724416025074 SALMON 3.00 5.99 BPF2508 724416025081 ALBACORE TUNA 3.00 5.99 BPF2509 724416925091 GAG GROUPER 3.00 5.99 BPF2510 724416125101 HOGFISH 3.00 5.99 BPF2512 724416025128 PACIFIC YELLOWTAIL 3.00 5.99 BPF2513 724416025135 BLUEFIN TUNA 3.00 5.99 BPF2515 724416025159 WHITE BASS 3.00 5.99 BPF9448 724416094483 GREAT WHITE 3.00 5.99 BPF9453 724416002198 LOBSTER 3.00 5.99 BPF9454 724416094544 PAC LOBSTER 3.00 5.99 B10 724416101105 REDFISH RIPPED 1.50 2.99 -

Southern Bluefin Tuna

Other sources of information SOUTHERN BLUEFIN TUNA This code of practice relates specifically to recreational fishing for Code of Practice - Recreational Fishery Southern Bluefin Tuna, but a lot of the practices described are just as relevant for other game fish species. For more information on best practices when recreational fishing for large pelagics and recreational fishing in general, the following links are useful: Recfish Australia National Code of Practice: Information for responsible www.recfishingresearch.org/national-code-of-practice/ catching, handling, releasing and Gamefishing Association of Australia Code of Practice for a Responsible Gamefish Fishery tagging of Southern Bluefin Tuna. www.gfaa.asn.au/new/index.php/gfaa-information/gfaa- principles-code-of-practice Tagging fish Neatfish: A standard for the National Environmental Assessment of Tournament Fishing Tagging fish provides data for research. For the tagging data www.neatfish.com to be useful the tagging needs to be done properly and the tagging event recorded accurately. The NSW-DPI Game Fish Ike jime (also available as a mobile device applicaiton) Tagging Program is currently the best source and repository of www.ikijime.com/fish/tuna-southern-bluefin recreational game fishing tags and data. New South Wales Department of Primary Industries Game Fish Tagging Program Tags (and associated data cards) can be sourced from GFAA www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fisheries/recreational/saltwater/gamefish- affiliated game fishing clubs. tagging It is best to tag the fish while it is still in the water, particularly Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and the for larger fish. Environment Tasmania www.dpipwe.tas.gov.au/sea-fishing-aquaculture/recreational- fishing/scalefish/tuna-fishing/ If applying the tag while the fish is out of the water ensure that it is carefully placed on a wet, padded surface. -

Worse Things Happen at Sea: the Welfare of Wild-Caught Fish

[ “One of the sayings of the Holy Prophet Muhammad(s) tells us: ‘If you must kill, kill without torture’” (Animals in Islam, 2010) Worse things happen at sea: the welfare of wild-caught fish Alison Mood fishcount.org.uk 2010 Acknowledgments Many thanks to Phil Brooke and Heather Pickett for reviewing this document. Phil also helped to devise the strategy presented in this report and wrote the final chapter. Cover photo credit: OAR/National Undersea Research Program (NURP). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/Dept of Commerce. 1 Contents Executive summary 4 Section 1: Introduction to fish welfare in commercial fishing 10 10 1 Introduction 2 Scope of this report 12 3 Fish are sentient beings 14 4 Summary of key welfare issues in commercial fishing 24 Section 2: Major fishing methods and their impact on animal welfare 25 25 5 Introduction to animal welfare aspects of fish capture 6 Trawling 26 7 Purse seining 32 8 Gill nets, tangle nets and trammel nets 40 9 Rod & line and hand line fishing 44 10 Trolling 47 11 Pole & line fishing 49 12 Long line fishing 52 13 Trapping 55 14 Harpooning 57 15 Use of live bait fish in fish capture 58 16 Summary of improving welfare during capture & landing 60 Section 3: Welfare of fish after capture 66 66 17 Processing of fish alive on landing 18 Introducing humane slaughter for wild-catch fish 68 Section 4: Reducing welfare impact by reducing numbers 70 70 19 How many fish are caught each year? 20 Reducing suffering by reducing numbers caught 73 Section 5: Towards more humane fishing 81 81 21 Better welfare improves fish quality 22 Key roles for improving welfare of wild-caught fish 84 23 Strategies for improving welfare of wild-caught fish 105 Glossary 108 Worse things happen at sea: the welfare of wild-caught fish 2 References 114 Appendix A 125 fishcount.org.uk 3 Executive summary Executive Summary 1 Introduction Perhaps the most inhumane practice of all is the use of small bait fish that are impaled alive on There is increasing scientific acceptance that fish hooks, as bait for fish such as tuna. -

STRIKE 2017 | PERTH GAME FISHING CLUB 2 Club Committee

PERTH GAME FISHING CLUB 2017 STRIKE 2017 | PERTH GAME FISHING CLUB 2 Club Committee ...........................................4 President’s Message ..................................5 Letter from the Editor .................................5 2016 Presentation Dinner .........................6 Shimano WA Open......................................8 Bluewater Tackle World CONTENTS Marlin Cup ................................................... 12 Exmouth Charter Fishing ......................... 16 Northern Adventure .................................. 19 Dampier Classic ........................................ 24 Carnavon Islands Mission .......................27 Tide Tables 2016 ...................................... 30 Rottnest Trench FAD Chart .................... 32 2016 FAD Season ......................................34 New Member’s Success ......................... 36 Rottnest Trench - Temperature Studies ............................... 38 Aitutaki – Cook Islands ........................... 40 Southern Bluefin Tuna ............................. 42 Club Rules and Trophy List .................... 50 Measure and Release 2017 ................... 52 GFAA Eligible Species ............................ 54 WA Game Fishing Records .................... 55 2017 Season Calendar ............................ 64 Front Cover: The images on the front cover have all been provided by club members. The collage is designed around the elements of the club’s activities being people, fish, boats, competition, fun and FADs. STRIKE 2017 | PERTH GAME FISHING -

Bodacc Bulletin Officiel Des Annonces Civiles Et

o Quarante-septième année. – N 228 A ISSN 0298-296X Mercredi 27 novembre 2013 BODACCBULLETIN OFFICIEL DES ANNONCES CIVILES ET COMMERCIALES ANNEXÉ AU JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE DIRECTION DE L’INFORMATION Standard......................................... 01-40-58-75-00 LÉGALE ET ADMINISTRATIVE Annonces....................................... 01-40-58-77-56 Accueil commercial....................... 01-40-15-70-10 26, rue Desaix, 75727 PARIS CEDEX 15 Abonnements................................. 01-40-15-67-77 www.dila.premier-ministre.gouv.fr (9 h à 12 h 30) www.bodacc.fr Télécopie........................................ 01-40-58-77-57 BODACC “A” Ventes et cessions - Créations d’établissements Procédures collectives Procédures de rétablissement personnel Avis relatifs aux successions Avis aux lecteurs Les autres catégories d’insertions sont publiées dans deux autres éditions séparées selon la répartition suivante Modifications diverses........................................ BODACC “B” Radiations ............................................................ } Avis de dépôt des comptes des sociétés ....... BODACC “C” Banque de données BODACC servie par les sociétés : Altares-D&B, EDD, Infogreffe, Questel SAS, Tessi (Defitech), Pouey International, Scores & Décisions, Les Echos, Creditsafe France, Coface Services, Cartegie, Infolegale & Marketing, France Telecom SA Kiosque Internet Entreprises, Telino, Docapost, Bureau Van Dijk EE (Bureau Van Dijk Electronic publishing), Tinubu, Data Project, Clic Formalités et Binq Media BV. Conformément à l’article 4 de l’arrêté du 17 mai 1984 relatif à la constitution et à la commercialisation d’une banque de données télématique des informations contenues dans le BODACC, le droit d’accès prévu par la loi no 78-17 du 6 janvier 1978 s’exerce auprès de la Direction de l’information légale et administrative. Le numéro : 3,65 € Abonnement. -

Wide-Beam Performance— for Tuna and Marlin Fishing

SS264W Tilted 1 kW Element ™ Pair Dual-Frequency Preliminary Wide-Beam performance — for tuna and marlin fishing. • Consists of two transducers: See the Wider Picture • SS264 50 kHz wide-beam Airmar has taken the SS270W wide-beam thru-hull • SS264 200 kHz wide-beam and split it apart into a Tilted Element™ transducer pair. The low-profile design is perfect for fast, trailered, • Excellent fish detection in tournament, sport-fishing vessels that cannot install a shallow to mid-water depths thru-hull with a high-performance fairing. These • Provides 4 times the transducers provide four times the beamwidth at beamwidth at 200 kHz than 200 kHz than other high-performance transducers. other high-performance This means marking more game fish and bait in a transducers larger area, increasing your catch. • Identical wide 25° beamwidths at 50 kHz and 200 kHz The Ultimate Split-Screen “Tunaducer” • Transducers can be purchased Since the beamwidths are the same at both as a pair for dual-frequency The high-performance wide-beam ceramic elements are tilted frequencies, a split-screen fishfinder display will clearly operation or individually as inside the housings, which compensates for your boats single-frequency units deadrise. This aims the beams straight toward the bottom, show the same water column and bottom coverage. resulting in strong echo returns and accurate depth readings. Fish will also appear as arches. More fish will be • No affect on your boats marked while trolling or underway. At anchor, see running performance which direction the baits and chum are flowing in the • Fixed 0°or 12° or 20° tilted current. -

Back Issue Directory

Canyon Annuals 1988 Canyon Annual Features: THE NIGHT SHIFT By Capt. Greg Ventura “DUE COURSE” TACTICS FOR BLUE MARLIN By Capt Ed Mossbrook OBJECTIVE: MAKO By Capt Matt Muzlslay THAT DAY IN JULY By Robert Raguso TAG & RELEASE TUNA By Capt Pete Barrett VIRGINIA IS FOR BILLFISH By Capt Al Paschall BAIT & LURE RIGGING By Dave Arbeitman & Grant Toman Meet The Pro’s: Dick Weber – White Marlin, Earl Croswell- Inshore Tuna, Bob Pisano- Giant Blue fin Tuna, Andy Pollack- Big eye Tuna, Leyer & Brodessor- Blue Marlin, Ron Bauer- Tuna Preparation Construction Report: By Capt Peter Fredericksen Striker Canyon Runner, 285 Mako & Blackwatch 30 Game fish Profile: THUNNUS THYNNUS: THE BLUE FIN TUNA By Bruce Freeman 1987 Correlation: THE CANYON SEASON IN REVIEW By Capt Len Belcaro 1989 Canyon Annual Features: MAKO TECHNIQUES By Capt Ralph Layer BENT ON TUNA By Capt Steve Bent BLOCK CANTON BLUES By Capt Adam Kibel YOU CAN’T CATCH ‘EM THE BEHIND PILINGS By Capt Joe Joachimowski TACTICS FOR GIANT BLUE FIN By Pete Rhein OFFSHORE EDDIES INFLUENCE INSHORE FISHING By Capt Mitch Chagnon THE INDOMITABLE BIG EYE By Ron Goldberg ON THE CANYON FLOOR By Capt Len Belcaro RIGGING MACKERAL DAISY CHAINS By Capt Greg Venturo SELECTING A STAND UP ROD By David Arbeitman & Grant Toman Meet The Pro’s: Pat Diantonio- Billfish, Richard Krupski- Mako Shark, Dale Dupuis- Blue Fin Tuna, Frank Pettolina- Tuna, John Keller- Tuna, Craig Norris- Tilefish Construction Report: By Capt Bill Brown Strike 26, Ocean Master 31, Albin 32, Viking 57 Game fish Profile: THE SHORTFIN MAKO SHARK By John G. -

Striped Marlin

Striped Marlin History of the Fishery In Mexican waters, striped marlin are taken for local mar- kets and export to other countries. These sheries include triped marlin (Tetrapturus audax) support important both artisan, using hand-hauled gillnets and longlines, and Scommercial and recreational sheries in the central larger drift net vessels targeting swordsh and sharks. and eastern Pacic and in the Indian oceans. They were The water off the southern tip of the Baja California directly targeted by high seas sheries in the 1960s and peninsula to Manzanillo, Mexico, is an area of high striped 1970s, although today most are taken as incidental catch marlin abundance, which supports a large recreational in tuna longline sheries. Pacic-wide landings currently shery. Mexican tourist enterprises aggressively advertise average near 26.5 million pounds per year and represent to attract billsh anglers to the area. The striped marlin about 86 percent of world landings. catch rate is greatly improved off Baja where anglers aver- Striped marlin are seasonal visitors to southern California age 0.3 to 0.65 striped marlin per day of shing. Estimated waters providing recreational billsh anglers an oppor- recreational catches of striped marlin off Los Cabos, Baja tunity to sh for local large gamesh during summer California Sur, averaged 12,000 sh annually between and fall. Recreational and commercial shing for striped 1992 and 1996, but only averaged 260 sh off Mazatlan. marlin began off southern California in the early-1900s The estimated incidental catch from the longline shark using hand-held harpoons or rod-and-reel. The California shery in Mazatlan averaged 680 striped marlin over the Legislature banned the use of harpoons to take striped same period.