CYCLOPEDIA of BIBLICAL, THEOLOGICAL and ECCLESIASTICAL LITERATURE Canticle - Census by James Strong & John Mcclintock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Almanacco Romano Pel 1855

AL!IANACCO RO}JANO pd· 1855 COJSTENENTB INDICAZIONJ, �OTIZIE ED INDIRIZZI l'ER LA. CITTÀ DI ROMA ] .. Pa:fti!o ANNO 't DaUa Tipografia di Gaetano Chin�Si Piazza Monte Citorio 119. AI�lUNACCO/ 9'\,.-"\ , ....- - . ROMANO OSSIA D-EI PRUilRI DIGNITARI .E FUNZIONARI INDllUZZI E NOTIZIE DI PUBBLICI STABILIJIJENTI, n' DEl DI SGIENZE, E PRIVATIED TI, PROFESSORI LETTERE AR DEl COMliERCIANTI, A T I TI EC. R S EC. PEL ·J855 ANNO I'Ril\10 ROi\lA CrHASSI MONTE 11� tll'O R:H'i.\ I>JAZZA Dl Ci'J'OI\10 �. Coltti che per semplice cu-riosità o ]Jer l'esi genza de' pr.op-ri affa-ri desiderasse conoscere L'organizzazione di questa nostra metropoli e i diversi rami delle professioni, arti mestieri; e invano avrebbe ricercato un almanacco che a colpo d'occhio e complessivamente avesse rispo sto alle . più ovvie e necessarie ricerche. Quelli che pm· lo innan�i vennero pubbliwti, rigttar davano soltanto delle categorie parzictli, ed in città, ove per le moltiplici giurisdizioni si una centralizzano e si compenetrano gli affari, o ve le agenzie rapp1·esentano i bisogni dì tutte le province, non hanno l1'miti che le separi, sem e pre più si sentiva il bisogno d'una raccolta ge nerale di tutte notizie che ad ogni ceto di per sone potessero recare interesse. Nello scopo di sopper·ire a questo vuoto ven'tamo alla pubblica zione del presente almanacco, nel quale anche olt-re l'organizzazione governativa ed wnmini strativa si sono raccolte le indicctzioni risgHar clanti il clero, la nobiltà, la curia, 1. -

SOKOL BOOKS LTD PO Box 2409 London W1A 2SH Tel: 020 7499 5571 Fax: 020 7629 6536 Email: [email protected]

SOKOL BOOKS LTD PO Box 2409 London W1A 2SH Tel: 020 7499 5571 Fax: 020 7629 6536 Email: [email protected] A Catalogue of Books Under £2,000 2010 Terms and Conditions 1) Postage and insurance (at 1% of catalogue price) are charged on all parcels unless otherwise specified. 2) Where payment is not made in sterling please add $15 or €15 to the total to cover bank charges. 3) Any book may be returned within 14 days for any reason. 4) Payment is due within 30 days of the invoice date. 5) All books remain our property until paid for in full. 6) We reserve the right to charge interest on outstanding invoices at our discretion. You are always very welcome to visit our Mayfair premises. Please contact us in advance, to avoid disappointment 1. AEMYLIUS, Paulus. Historia delle cose di Francia. Venice, Michele Tramezzino, 1549 FIRST EDITION thus. 4to ff. [xxviii] 354[ ii]. Italic letter, woodcut printer's device of the Sybilline Oracle on title, another similar on blank verso of last, fine nine line historiated woodcut initials, two early autographs inked over on title, '1549' in contemp. hand at head, ms. press mark to f.f.e-p. ink stain to gutter and lower margin of ss1 and 2, very light marginal foxing in places, the occasional marginal thumb mark or stain. A very good, clean, well margined copy in contemporary limp vellum, yapp edges, early restoration to outer edge on upper cover. £1,450 First Italian edition of Aemylius' interesting and pioneering history of the French Kings, and the first edition in the vernacular; the french translation of the latin by Regnart, published by Morel, did not appear until 1581. -

Università Degli Studi Di Roma “Roma Tre”

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI ROMA “ROMA TRE” Facoltà di Lettere e Filosofia DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN Storia (politica, società, culture, territorio) XXIV CICLO CARCERI E DETENUTI A BOLOGNA TRA ETÁ NAPOLEONICA E RESTAURAZIONE PONTIFICIA Maria Romana Caforio Tutor: prof. Stefano Andretta Coordinatore: prof. ssa Francesca Cantù Anno Accademico 2012 / 2013 Indice Abbreviazioni 5 Introduzione 9 I. Legislazione penale e istituti di reclusione tra fine Settecento ed Età francese 1. L’antico regime 21 2. L’avvento dei francesi a Bologna e i nuovi luoghi pena 42 3. Le nuove case di condanna nella rete carceraria napoleonica (1802-1809) 60 4. Il San Michele in Bosco nel sistema penitenziario dell’Impero 70 II. Legislazione penale e penitenziari dalla Restaurazione pontificia a Pio IX 1. Pio VII e Ercole Consalvi nella riorganizzazione del sistema carcerario pontificio 87 2. Istituti di internamento nell’età della Restaurazione: il Forte Urbano e il Discolato 103 3. Carceri bolognesi e prigioni papali nell’età delle riforme europee (1830-1845) 125 4. Bologna nel Pontificato di Pio IX. Speranze e riforme 146 III. Il personale di sorveglianza: reclutamento, compiti ed evoluzione della figura del secondino 1 1. Modalità di reclutamento del personale di sorveglianza in età napoleonica e pontificia 169 2. Esercitare la sorveglianza: condizioni di lavoro, inconvenienti, abusi e rimedi 179 3. A ciascun recluso il proprio sorvegliante: modelli di custodia maschili, femminili e minorili tra Regime pontificio e Unità d’Italia 187 IV. Le carceri tra interno ed esterno 1. L’ordine imposto tra norma e prassi 201 2. Élite e miserabili 212 3. Famiglie, istituzioni, reclusi 222 4. -

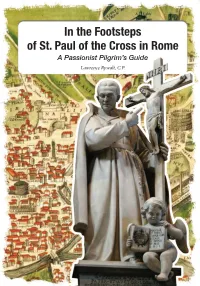

In the Footsteps of St. Paul of the Cross in Rome a Passionist Pilgrim’S Guide Lawrence Rywalt, C.P

In the Footsteps of St. Paul of the Cross in Rome A Passionist Pilgrim’s Guide Lawrence Rywalt, C.P. Cum permissu: Joachim Rego, C.P. Superior General 1st printing June 2017 Graphics: Andrea Marzolla Cover photograph: Statue of St. Paul of the Cross, St. Peter’s Basilica Congregation of the Passion of Jesus Christ In the Footsteps of St. Paul of the Cross in Rome A Passionist Pilgrim’s Guide Lawrence Rywalt, C.P. Curia Generalizia dei Passionisti, P.zza SS. Giovanni e Paolo 13 00184 Roma (RM) Table of Contents Introduction Casa mia! Casa mia! 5 Itinerary 1: The Celio Hill 1.1 The Basilica and Monastery of Sts. John and Paul 7 1.2 The Basilica of Santa Maria in Domnica (the “Navicella”) 10 1.3 The Hospice of the Most Holy Crucifix 12 1.4 The Basilica of St. John Lateran 15 Itinerary 2: The Esquiline Hill and the district of the “Monti” (hills) 2.1 The Basilica of St. Mary Major 17 2.2 The Church of the “Madonna ai Monti” 19 Itinerary 3: The Trastevere district 3.1 The Tiberina Island and the Church and the College of St. Bartholomew 21 3.2 The Hospital of San Gallicano 23 3.3 The Church of Santa Maria in Trastevere 28 Itinerary 4: The Lungotevere district and the Vatican 4.1 The “Ponte Sisto” Bridge and Hospice and Pilgrims’ Church of the Most Holy Trinity (SS. Trinità dei Pellegrini) 30 4.2 The Church of San Giovanni dei Fiorentini 33 4.3 St. Peter’s Basilica -- the Canons’ Chapel of the Immaculate Conception (“l’Immacolata” / dei Canonici) and the Statue of St. -

•Impag Ita PASSIONISTI Parte Iniziale 11 2 11

Scrivere la storia dei passionisti dal 1839 al 1863 significa, prima di tutto, evocare i passi di un’istituzione religiosa profondamente inserita nella vita della chiesa. Le difficoltà della cristianità in questo periodo si ripercossero sulla stabilità dell’istituto. Ma lo spinsero anche a portare la spiritualità e il messaggio della Croce a nuovi ambienti fuori d’Italia: Belgio, Francia, Austra lia, Inghilterra e Stati Uniti. La beatificazione di Giovanni Enrico Newman (19 settembre 2010) ha offerto l’opportunità di evocare la presenza del passioni- sta beato Domenico Barberi nel cammino della sua conversione e del suo in gresso nella Chiesa Cattolica il 9 ottobre 1845. Una nota tipica di questo periodo è la coincidenza con gli anni di governo dello stesso superiore generale, P. Antonio di S. Giacomo Testa, che vanno dall’aprile del 1839 ad agosto del 1862. Dovettero essere disattese più di ses santa richieste per aprire nuovi ritiri o conventi, o perché le domande supera vano la disponibilità di personale, o perché erano in pericolo i valori tradizio nali dell’istituto, come la solitudine o l’apostolato delle missioni popolari. Il P. Testa si mantenne aperto alle necessità della Chiesa, ma nello spesso tempo vigilante, perché non s’introducessero semi di rilassamento nelle comunità. Personaggi significativi di questo periodo sono, oltre al P. Testa, il papa beato Pio IX (1846 - 1878), il già menzionato B. Domenico Barberi (+ 1849), Giorgio Spencer, convertito dall’anglicanesimo, poi passionista col nome di P. Ignazio di S. Paolo (+ 1864), e l’apostolo dell’infanzia spirituale con la devo zione al Bambino Gesù, B. -

Ad Multos Annos

erattivo N eractive º 1 eractivo – eractif 2 eraktiv 0 1 2 Ordine di Sant’Agostino Order of Saint Augustine Orden de San Agustín O u A r d M C u l t a o s r A d n n o i s n a l In this issue front page: 3. Editorial 3. His Eminence Prospero Cardinal Grech 5. Augustinian Cardinals: 19th - 20th Centuries OSA INTeractive 7. Other Cardinals of the Augustinian Order 1-2012 augustinian family : Editorial board: Michael Di Gregorio, OSA 8. Provincial Chapter: Province of Quito, Ecuador Robert Guessetto, OSA Melchor Mirador, OSA 9. FANA: Federation of Augustinians of North America Collaborators: 10. Second Meeting of Young Augustinians of Europe Leonardo Andrés Andrade, OSA Manuel Calderon, OSA 12. Episcopal Ordination of His Eminence Prospero Card. Grech Giuseppe Caruso, OSA Osman Choque, OSA 13. Creation as Cardinal of His Eminence Prospero Card. Grech Gennaro Comentale, OSA José Gallardo, OSA 14. Contemplative Nuns Prepare for Assembly Jean Gray Prospero Grech, OSA Claudia Kock 15. Asia-Pacific Renewal Program Gathers Friars in Japan Paulo Lopez, OSA Robert Marsh, OSA 16. St. Augustine’s College in Abuja, Nigeria Miguel Angel Martín Juarez, OSA Edelmiro Mateos, OSA 17. Rapid Growth at Augustinian School in India Françoise Pernot José Fernando Rubio 18. Peru: The Indigenous Kukama of Nauta Mauricio Saavedra, OSA Rafael Santana 19. Workshop for Vocation Promotors José Souto, OSA Veronica Vandoni 19. Itineraries for Augustinian Contemplation Graphic, layout and printing: 20. Lay Augustinian Congress Tipolitografia 2000 sas De Magistris R. & C. 21. Congress of Augustinian Educators and Schools Via Trento 46, Grottaferrata (Rm) 22.