The Trojan Horse of Corporate Responsibility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freedom of Information Act Activity for the Weeks of December 29, 2016-January 4, 2017 Privacy Office January 10, 2017 Weekly Freedom of Information Act Report

Freedom of Information Act Activity for the Weeks of December 29, 2016-January 4, 2017 Privacy Office January 10, 2017 Weekly Freedom of Information Act Report I. Efficiency and Transparency—Steps taken to increase transparency and make forms and processes used by the general public more user-friendly, particularly web- based and Freedom of Information Act related items: • NSTR II. On Freedom of Information Act Requests • On December 30, 2016, Bradley Moss, a representative with the James Madison Project in Washington D.C, requested from Department of Homeland Security (DI-IS) Secret Service records, including cross-references, memorializing written communications — including USSS documentation summarizing verbal communications —between USSS and the transition campaign staff, corporate staff, or private staff of President-Elect Donald J. Trump. (Case Number HQ 2017-HQF0-00202.) • On December 30, 2016, Justin McCarthy, a representative with Judicial Watch in Washington, D.C., requested from United States Secret Service (USSS) records concerning the use of U.S. Government funds to provide security for President Obama's November 2016 trip to Florida. (Case Number USSS 20170407.) • On January 3,2017, Justin McCarthy, a representative with Judicial Watch in Washington, DE, requested from United States Secret Service (USSS) records concerning, regarding, or relating to security expenses for President Barack °ham's residence in Chicago, Illinois from January 20, 2009 to January 3,2017. (Case Number USSS 20170417.) • On January 3,2017, Justin McCarthy, a representative with Judicial Watch in Washington, D.C., requested from United States Secret Service (USSS) records concerning, regarding. or relating to security expenses for President-Elect Donald Trump and Trump Tower in New York, New York from November 9,2016 to January 3,2017. -

Drowning in Data 15 3

BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE WHAT THE GOVERNMENT DOES WITH AMERICANS’ DATA Rachel Levinson-Waldman Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law about the brennan center for justice The Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law is a nonpartisan law and policy institute that seeks to improve our systems of democracy and justice. We work to hold our political institutions and laws accountable to the twin American ideals of democracy and equal justice for all. The Center’s work ranges from voting rights to campaign finance reform, from racial justice in criminal law to Constitutional protection in the fight against terrorism. A singular institution — part think tank, part public interest law firm, part advocacy group, part communications hub — the Brennan Center seeks meaningful, measurable change in the systems by which our nation is governed. about the brennan center’s liberty and national security program The Brennan Center’s Liberty and National Security Program works to advance effective national security policies that respect Constitutional values and the rule of law, using innovative policy recommendations, litigation, and public advocacy. The program focuses on government transparency and accountability; domestic counterterrorism policies and their effects on privacy and First Amendment freedoms; detainee policy, including the detention, interrogation, and trial of terrorist suspects; and the need to safeguard our system of checks and balances. about the author Rachel Levinson-Waldman serves as Counsel to the Brennan Center’s Liberty and National Security Program, which seeks to advance effective national security policies that respect constitutional values and the rule of law. -

S:\FULLCO~1\HEARIN~1\Committee Print 2018\Henry\Jan. 9 Report

Embargoed for Media Publication / Coverage until 6:00AM EST Wednesday, January 10. 1 115TH CONGRESS " ! S. PRT. 2d Session COMMITTEE PRINT 115–21 PUTIN’S ASYMMETRIC ASSAULT ON DEMOCRACY IN RUSSIA AND EUROPE: IMPLICATIONS FOR U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY A MINORITY STAFF REPORT PREPARED FOR THE USE OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JANUARY 10, 2018 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations Available via World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 28–110 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 04:06 Jan 09, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5012 Sfmt 5012 S:\FULL COMMITTEE\HEARING FILES\COMMITTEE PRINT 2018\HENRY\JAN. 9 REPORT FOREI-42327 with DISTILLER seneagle Embargoed for Media Publication / Coverage until 6:00AM EST Wednesday, January 10. COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS BOB CORKER, Tennessee, Chairman JAMES E. RISCH, Idaho BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland MARCO RUBIO, Florida ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey RON JOHNSON, Wisconsin JEANNE SHAHEEN, New Hampshire JEFF FLAKE, Arizona CHRISTOPHER A. COONS, Delaware CORY GARDNER, Colorado TOM UDALL, New Mexico TODD YOUNG, Indiana CHRISTOPHER MURPHY, Connecticut JOHN BARRASSO, Wyoming TIM KAINE, Virginia JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts ROB PORTMAN, Ohio JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon RAND PAUL, Kentucky CORY A. BOOKER, New Jersey TODD WOMACK, Staff Director JESSICA LEWIS, Democratic Staff Director JOHN DUTTON, Chief Clerk (II) VerDate Mar 15 2010 04:06 Jan 09, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\FULL COMMITTEE\HEARING FILES\COMMITTEE PRINT 2018\HENRY\JAN. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the DISTRICT of COLUMBIA ______) ELECTRONIC PRIVACY INFORMATION ) CENTER, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) V

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA _______________________________________ ) ELECTRONIC PRIVACY INFORMATION ) CENTER, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 19-810 (RBW) ) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ) JUSTICE, ) ) Defendant. ) _______________________________________) ) JASON LEOPOLD & ) BUZZFEED, INC., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 19-957 (RBW) ) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ) JUSTICE, et al., ) ) Defendants. ) _______________________________________) MEMORANDUM OPINION The above-captioned matters concern requests made by the Electronic Privacy Information Center (“EPIC”) and Jason Leopold and Buzzfeed, Inc. (the “Leopold plaintiffs”) (collectively, the “plaintiffs”) to the United States Department of Justice (the “Department”) pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”), 5 U.S.C. § 552 (2018), seeking, inter alia, the release of an unredacted version of the report prepared by Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller III (“Special Counsel Mueller”) regarding his investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 United States presidential election (the “Mueller Report”). See Complaint ¶¶ 2, 43, Elec. Privacy Info. Ctr. v. U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Civ. Action No. 19-810 (“EPIC Compl.”); Complaint ¶ 1, Leopold v. U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Civ. Action No. 19-957 (“Leopold Pls.’ Compl.”). Currently pending before the Court are (1) the Department of Justice’s Motion for Summary Judgment in Leopold v. Department of Justice and Partial Summary Judgment in Electronic Privacy Information Center v. Department of Justice (“Def.’s Mot.” or the “Department’s motion”); (2) the Plaintiff’s Combined Opposition to Defendant’s Motion for Partial Summary Judgment, Cross-Motion for Partial Summary Judgment, and Motion for In Camera Review of the “Mueller Report” (“EPIC’s Mot.” or “EPIC’s motion”); and (3) Plaintiffs Jason Leopold’s and Buzzfeed Inc.’s Motion for Summary Judgment (“Leopold Pls.’ Mot.” or the “Leopold plaintiffs’ motion”). -

The Fraudulent War, Was Assembled in 2008

Explanatory note The presentation to follow, entitled The Fraudulent War, was assembled in 2008. It documents the appalling duplicity and criminality of the George W. Bush Administration in orchestrating the so-called “global war on terror.” A sordid story, virtually none of it ever appeared in the mainstream media in the U.S. Given the intensity of the anti-war movement at the time, the presentation enjoyed some limited exposure on the Internet. But anti-war sentiment was challenged in 2009 by Barack Obama's indifference to his predecessor's criminality, when the new president chose “to look forward, not backward.” The “war on terror” became background noise. The Fraudulent War was consigned to an archive on the ColdType website, a progressive publication in Toronto edited by Canadian Tony Sutton. There it faded from view. Enter CodePink and the People's Tribunal on the Iraq War. Through testimony and documentation the truth of the travesty was finally disclosed, and the record preserved in the Library of Congress. Only CodePink's initiative prevented the Bush crimes from disappearing altogether, and no greater public service could be rendered. The Fraudulent War was relevant once more. It was clearly dated, the author noted, but facts remained facts. Richard W. Behan, November, 2016 ------------------------------------------------- The author—a retired professor—was outraged after reading a book in 2002 subtitled, “The Case for Invading Iraq.” Unprovoked aggression is prohibited by the United Nations charter, so he took to his keyboard and the Common Dreams website in vigorous dissent. Within months thereafter George Bush indeed invaded the sovereign nation of Iraq, committing an international crime. -

JASON LEOPOLD and ) BUZZFEED, INC., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) V

Case 1:19-cv-01278-RBW Document 47 Filed 11/28/19 Page 1 of 4 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA _______________________________________ ) JASON LEOPOLD and ) BUZZFEED, INC., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 19-1278 (RBW) ) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ) JUSTICE, et al., ) ) Defendants. ) _______________________________________) ) CABLE NEWS NETWORK, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 19-1626 (RBW) ) FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION, ) ) Defendant. ) _______________________________________) ORDER In accordance with the oral rulings issued by the Court at the status conference held on November 25, 2019, it is hereby ORDERED that, on or before December 2, 2019, the United States Department of Justice (the “Department”) shall produce to Jason Leopold and Buzzfeed, Inc. (collectively, the “Leopold plaintiffs”) and Cable News Network (“CNN”) the FD-302 forms, including any handwritten notes and attachments to the typewritten narrative, created by the Federal Bureau of Case 1:19-cv-01278-RBW Document 47 Filed 11/28/19 Page 2 of 4 Investigation (the “FBI”), in accordance with the terms of the Court's October 3, 2019 Order, ECF No. 33.1 It is further ORDERED that the Plaintiffs’ Combined Motion for Preliminary Injunction and Memo in Support, ECF No. 43, is GRANTED IN PART AND DENIED WITHOUT PREJUDICE IN PART. It is GRANTED to the extent that it seeks the processing and production of the Leopold plaintiffs’ request for the summaries of the report regarding Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 United States presidential election (the “Mueller Report”) prepared by the Office of Special Counsel Mueller (“Special Counsel Mueller’s Office”).2 It is DENIED WITHOUT PREJUDICE in all other respects. -

Testimony of Ambassador Michael Mcfaul1

Testimony of Ambassador Michael McFaul1 Hearing of the House Permanent Select Committee of Intelligence Putin’s Playbook: The Kremlin’s Use of Oligarchs, Money and Intelligence in 2016 and Beyond March 28, 2019 When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the worldwide ideological struggle between communism and liberalism – in other words, freedom, democracy, capitalism – also ended. Thankfully, the ideological contest between Moscow and Washington that shaped much of world politics for several decades in the twentieth century has not reemerged. However, for at least a decade now, Russian president Vladimir Putin has been waging a new ideological struggle, first at home, and then against the West more generally, and the United States in particular. He defines this contest as a battle between the decadent, liberal multilateralism that dominates in the West and his brand of moral, conservative, sovereign values. I define this contest as one between autocracy, corruption, state domination of the economy, and indifference to international norms versus democracy, rule of law, free markets, and respect for international law. This new ideological struggle is primarily being waged not between states, but within states. At home, Putin has eroded checks and balances on executive power, undermined the autonomy of political actors, regional governments, the media, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and strengthened state ownership throughout the Russian economy. To propagate his ideas and pursue his objectives abroad, Putin has invested in several powerful instruments of influence, many of which parallel those used for governing within Russia, including traditional media, social media, the weaponization of intelligence (doxing), financial support for allies, business deals for political aims, and even the deployment of coercive actors abroad, including soldiers, mercenaries, and assassins. -

Southern California Journalism Awards

LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB FIFTY-NINTH ANNUAL5 SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA 9JOURNALISM AWARDS th 59 ANNUAL SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA JOURNALISM AWARDS A Letter From the President CONGRATULATIONS t’s a challenging time for sure. We’ve all been warned more than once JAIME JARRIN by now. We’ve all heard the message, “The media is in trouble.” I Journalists are mistrusted, misrepresented, maligned. We’ve taken it on the chin in both red states and blue states. FOR RECEIVING THE BILL ROSENDAHL But as songwriter and Visionary Award winner Diane Warren told the PUBLIC SERVICE AWARD Los Angeles Press Club last December, “We need you now more than ever.” Not to worry, as the Los Angeles Press Club is not going anywhere. HONORING YOUR COMMUNITY CONTRIBUTIONS We remain one of the oldest organizations in the nation dedicated to representing and defending journalists—and the Free Press. Our democracy THE LOS ANGELES DODGERS ARE PROUD OF YOUR depends on it. But tonight, we come together to celebrate our colleagues, our fellow ACCOMPLISHMENTS BOTH AS THE TEAM’S SPANISH LANGUAGE journalists. Congratulations to all of the nominees for the 59th Annual VOICE FOR NEARLY 60 YEARS AND YOUR SERVICE AND Southern California Journalism Awards. Submissions this year shattered COMMITMENT TO THE CITY’S HISPANIC COMMUNITY. the previous record as press clubs from around the country, including the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., were called upon to judge more WE ARE HONORED THAT YOU WILL ALWAYS BE PART than 1,200 entries. OF OUR DODGER FAMILY. Robert Kovacik It is also a privilege to welcome our Honorary Awardees, selected by our Board of Directors for their contributions to our industry and our society. -

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform Jason Chaffetz (UT-3), Chairman

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform Jason Chaffetz (UT-3), Chairman FOIA Is Broken: A Report Staff Report 114th Congress January 2016 “The Freedom of Information Act should be administered with a clear presumption: In the face of doubt, openness prevails. All agencies should adopt a presumption in favor of disclosure, in order to renew their commitment to the principles embodied in FOIA, and to usher in a new era of open Government. The presumption of disclosure should be applied to all decisions involving FOIA.” --President Barack Obama January 21, 2009 “Despite prior admonitions from this Court and others, EPA continues to demonstrate a lack of respect for the FOIA process. The Court is left wonder whether EPA has learned from its mistakes or if it will merely continue to address FOIA requests in the clumsy manner that has seemingly become its custom. Given the offensively unapologetic nature of EPA’s recent withdrawal notice, the Court is not optimistic that the agency has learned anything.” --Landmark Legal v. EPA, No. 12-1726 (D.D.C.) March 2, 2015 i Executive Summary Since President Lyndon Johnson signed the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) in 1966, the FOIA request has been used millions of times for a myriad of reasons. FOIA is one of the central tools to create transparency in the Federal government. FOIA should be a valuable mechanism protecting against an insulated government operating in the dark, giving the American people the access to the government they deserve. As such, FOIA’s promise is central to the Committee’s mission of increasing transparency throughout the Federal government. -

Homeland Security Washington, DC 20528

U.S. Department of Homeland Security Washington, DC 20528 Homeland Security Privacy Office, Mail Stop 0655 Re: This is the final response to your Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), dated December 26, 2019, and received by this office on December 26, 2019. You are seeking a copy of the letter of request for each of the ten oldest pending requests at DHS Privacy Office as amended on January 13, 2020. A search of Department of Homeland Security’s, Privacy Office for documents responsive to your request produced a total of forty-five (45) pages. Of those pages, I have determined that twenty-eight (28) pages of the records are releasable in their entirety and seventeen (17) pages are partially releasable pursuant to Title 5 U.S.C. § 552 (b)(6), FOIA Exemptions 6. Enclosed are seventeen (17) pages with certain information withheld as described below: FOIA Exemption 6 exempts from disclosure personnel or medical files and similar files the release of which would cause a clearly unwarranted invasion of personal privacy. This requires a balancing of the public’s right to disclosure against the individual’s right to privacy. The privacy interests of the individuals in the records you have requested outweigh any minimal public interest in disclosure of the information. Any private interest you may have in that information does not factor into the aforementioned balancing test. You have a right to appeal the above withholding determination. Should you wish to do so, you must send your appeal and a copy of this letter, within 90 days of the date of this letter, to: Privacy Office, Attn: FOIA Appeals, U.S. -

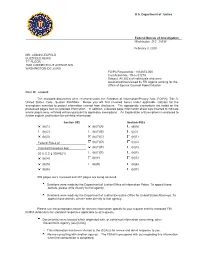

Buzzfeed FOIA Release of Mueller Report FBI 302 Reports

86'HSDUWPHQWRI-XVWLFH )HGHUDO%XUHDXRI,QYHVWLJDWLRQ Washington, D.C. 20535 )HEUXDU\ 05-$621/(232/' %8==)(('1(:6 7+)/225 &211(&7,&87$9(18(1: :$6+,1*721'& )2,3$5HTXHVW1R &LYLO$FWLRQ1RFY 6XEMHFW$OO¶VRILQGLYLGXDOVZKRZHUH TXHVWLRQHGLQWHUYLHZHGE\)%,$JHQWVZRUNLQJIRUWKH 2IILFHRI6SHFLDO&RXQVHO5REHUW0XHOOHU 'HDU0U/HRSROG 7KH HQFORVHG GRFXPHQWV ZHUH UHYLHZHG XQGHU WKH )UHHGRP RI ,QIRUPDWLRQ3ULYDF\$FWV )2,3$ 7LWOH 8QLWHG 6WDWHV &RGH 6HFWLRQ D %HORZ \RX ZLOO ILQG FKHFNHG ER[HV XQGHU DSSOLFDEOH VWDWXWHV IRU WKH H[HPSWLRQVDVVHUWHGWRSURWHFWLQIRUPDWLRQH[HPSWIURPGLVFORVXUH 7KHDSSURSULDWHH[HPSWLRQVDUHQRWHGRQWKH SURFHVVHGSDJHVQH[WWRUHGDFWHGLQIRUPDWLRQ ,QDGGLWLRQDGHOHWHGSDJHLQIRUPDWLRQVKHHWZDVLQVHUWHGWRLQGLFDWH ZKHUHSDJHVZHUHZLWKKHOGHQWLUHO\SXUVXDQWWRDSSOLFDEOHH[HPSWLRQV $Q([SODQDWLRQRI([HPSWLRQVLVHQFORVHGWR IXUWKHUH[SODLQMXVWLILFDWLRQIRUZLWKKHOGLQIRUPDWLRQ 6HFWLRQ 6HFWLRQD E E $ G E E % M E E & N E ' N )HGHUDO5XOHVRI E ( N &ULPLQDO3URFHGXUH H E ) N 86& L E E N E E N E N SDJHVZHUHUHYLHZHGDQGSDJHVDUHEHLQJUHOHDVHG 'HOHWLRQVZHUHPDGHE\WKH'HSDUWPHQWRI-XVWLFH2IILFHRI,QIRUPDWLRQ3ROLF\7RDSSHDOWKRVH GHQLDOVSOHDVHZULWHGLUHFWO\WRWKDWDJHQF\ 'HOHWLRQVZHUHPDGHE\WKH'HSDUWPHQWRI-XVWLFH([HFXWLYH2IILFHIRU8QLWHG6WDWHV$WWRUQH\V7R DSSHDOWKRVHGHQLDOVSOHDVHZULWHGLUHFWO\WRWKDWDJHQF\ 3OHDVHVHHWKHSDUDJUDSKVEHORZIRUUHOHYDQWLQIRUPDWLRQVSHFLILFWR\RXUUHTXHVWDQGWKHHQFORVHG)%, )2,3$$GGHQGXPIRUVWDQGDUGUHVSRQVHVDSSOLFDEOHWRDOOUHTXHVWV 'RFXPHQW V ZHUHORFDWHGZKLFKRULJLQDWHGZLWKRUFRQWDLQHGLQIRUPDWLRQFRQFHUQLQJRWKHU *RYHUQPHQW$JHQF\ -

1 United States District Court for the District Of

Case 1:15-cv-00999 Document 1 Filed 06/24/15 Page 1 of 16 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA JASON LEOPOLD, ) ) ) Judge _____________ ) Civil Action No. ____________ and ) ) ) ALEXA O’BRIEN, ) ) ) ) ) vs. ) ) NATIONAL SECURITY AGENCY, ) 9800 Savage Rd. ) Fort Meade, MD 20755, ) ) ) DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND ) SECURITY, ) 245 Murray Lane, SW ) Washington, DC 20528 ) ) ) DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, ) 950 Pennsylvania Ave., NW ) Washington, DC 20530, ) ) DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE, ) ) 1400 Defense Pentagon ) Washington, DC 20301-1400, ) ) CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY, ) Washington, DC 20505 ) ) and ) ) DEPARTMENT OF STATE, ) 2201 C St., NW ) Washington, DC 20520 ) ) ) DEFENDANTS ) 1 Case 1:15-cv-00999 Document 1 Filed 06/24/15 Page 2 of 16 COMPLAINT THE PARTIES 1. Plaintiff Jason Leopold is a citizen of California. 2. Mr. Leopold is an investigative reporter for VICE News covering a wide-range of issues, including Guantanamo, national security, counterterrorism, civil liberties, human rights, and open government. Additionally, his reporting has been published in The Guardian, The Wall Street Journal, The Financial Times, Salon, CBS Marketwatch, The Los Angeles Times, The Nation, Truthout, Al Jazeera English and Al Jazeera America. 3. Plaintiff Alexa O’Brien is a citizen of New York. 4. Ms. O’Brien is a national security investigative journalist. Her work has been published in The Cairo Review of Global Affairs, Guardian UK, Salon, and The Daily Beast, and she has been featured on BBC, PBS’ Frontline, On The Media, and Public Radio International. For her “outstanding work” she was shortlisted for the 2013 Martha Gellhorn Prize for Journalism in the UK. 5.