Why You Watch What You Watch When You Watch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

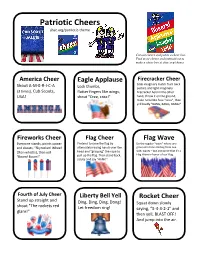

Patriotic Cheers Shac.Org/Patriotic-Theme

Patriotic Cheers shac.org/patriotic-theme Cut out cheers and put in a cheer box. Find more cheers and instructions to make a cheer box at shac.org/cheers. America Cheer Eagle Applause Firecracker Cheer Shout A-M-E-R-I-C-A Grab imaginary match from back Lock thumbs, pocket, and light imaginary (3 times), Cub Scouts, flutter fingers like wings, firecracker held in the other USA! shout "Cree, cree!" hand, throw it on the ground, make noise like fuse "sssss", then yell loudly "BANG, BANG, BANG!" Fireworks Cheer Flag Cheer Flag Wave Everyone stands, points upward Pretend to raise the flag by Do the regular “wave” where one and shouts, “Skyrocket! Whee!” alternately raising hands over the group at a time starting from one (then whistle), then yell head and “grasping” the rope to side, waves – but announce that it’s a Flag Wave in honor of our Flag. “Boom! Boom!” pull up the flag. Then stand back, salute and say “Ahhh!” Fourth of July Cheer Liberty Bell Yell Rocket Cheer Stand up straight and Ding, Ding, Ding, Dong! Squat down slowly shout "The rockets red Let freedom ring! saying, “5-4-3-2-1” and glare!" then yell, BLAST OFF! And jump into the air. Patriotic Cheer Mount New Citizen Cheer To recognize the hard work of Shout “U.S.A!” and thrust hand learning in order to pass the test with doubled up fist skyward Rushmore Cheer to become a new citizen, have while shouting “Hooray for the Washington, Jefferson, everyone stand, make a salute, Red, White and Blue!” Lincoln, Roosevelt! and say “We salute you!” Soldier Cheer Statue of Liberty USA-BSA Cheer Stand at attention and Cheer One group yells, “USA!” The salute. -

Buckaroo Banzai

WORLD WATCH ONE _ IN THIS ISSUE Corrected Edition: With apologies to Radford Polinsky for a misspelling of his name on page 44 of the original edition Introduction from the Editor Dan “Big Shoulders” Berger, Libertyville, IL Page 1 By the Oath of the Flying Fish! Sean “Figment” Murphy, Burke, VA Page 2 Oh, those Pesky Dimensional Barriers... Steve “Rainbow Kitty” Mattsson, Portland, OR Page 3 What’s Crushing the Watermelon? Dan Berger and Sean Murphy Pages 4-5 The Essential Blue Blaze Irregular Edited by Dan Berger Pages 6-12 3M Mask Modification Bryian “Cyclone One” Winner Page 13 INTERVIEW: Reno and Perfect Tommy Vetted for publication by Reno of Memphis Pages 14-15 An Oral History of the Birth of Banzai Compiled by Sean Murphy Pages 16-17 A Buckaroo Banzai Sampler Sean Murphy Pages 18-22 A Buckaroo Banzai Aperitif Dan Berger Pages 23-25 An Oral History of Buckaroo Banzai: Ancient Secrets & New Mysteries—Introduction Dan Berger Pages 26-27 Creating the Banzai Institute Website Dan Berger Pages 28-30 Visualizing Ancient Secrets & New Mysteries Sean Murphy Pages 31-33 Creating the CGI Jet Car Trailer Sean Murphy Pages 34-36 Creating the Jet Car Model, et al. Dan Berger Page 37 The Final Word on Pitching Sean Murphy and Dan Berger Pages 38-39 Banzai TV: The Kevin Smith Experience Dan Berger Pages 40-42 “Evil, Pure and Simple!” Scott “Camelot” Tate, Alamosa, CO Page 43 The Cheers/Lectroid Connections Scott Tate Page 43 Banzai Institute Alert! DeWayne “Buckaroo Trooper” Todd Pages 44-45 From the Bureau Office World Watch One Staff Page 46 What Makes My Potato Tick! Doug Drexler, Los Angeles, CA Back Cover Acknowledgements Once again, a host of BBIs—many of them first-time contributors to World Watch One—gathered together to help make this issue possible. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

Blacks Reveal TV Loyalty

Page 1 1 of 1 DOCUMENT Advertising Age November 18, 1991 Blacks reveal TV loyalty SECTION: MEDIA; Media Works; Tracking Shares; Pg. 28 LENGTH: 537 words While overall ratings for the Big 3 networks continue to decline, a BBDO Worldwide analysis of data from Nielsen Media Research shows that blacks in the U.S. are watching network TV in record numbers. "Television Viewing Among Blacks" shows that TV viewing within black households is 48% higher than all other households. In 1990, black households viewed an average 69.8 hours of TV a week. Non-black households watched an average 47.1 hours. The three highest-rated prime-time series among black audiences are "A Different World," "The Cosby Show" and "Fresh Prince of Bel Air," Nielsen said. All are on NBC and all feature blacks. "Advertisers and marketers are mainly concerned with age and income, and not race," said Doug Alligood, VP-special markets at BBDO, New York. "Advertisers and marketers target shows that have a broader appeal and can generate a large viewing audience." Mr. Alligood said this can have significant implications for general-market advertisers that also need to reach blacks. "If you are running a general ad campaign, you will underdeliver black consumers," he said. "If you can offset that delivery with those shows that they watch heavily, you will get a small composition vs. the overall audience." Hit shows -- such as ABC's "Roseanne" and CBS' "Murphy Brown" and "Designing Women" -- had lower ratings with black audiences than with the general population because "there is very little recognition that blacks exist" in those shows. -

Summer 2019 Calendar of Events

summer 2019 Calendar of events Hans Christian Andersen Music and lyrics by Frank Loesser Book and additional lyrics by Timothy Allen McDonald Directed by Rives Collins In this issue July 13–28 Ethel M. Barber Theater 2 The next big things Machinal by Sophie Treadwell 14 Student comedians keep ’em laughing Directed by Joanie Schultz 20 Comedy in the curriculum October 25–November 10 Josephine Louis Theater 24 Our community 28 Faculty focus Fun Home Book and lyrics by Lisa Kron 32 Alumni achievements Music by Jeanine Tesori Directed by Roger Ellis 36 In memory November 8–24 37 Communicating gratitude Ethel M. Barber Theater Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare Directed by Danielle Roos January 31–February 9 Josephine Louis Theater Information and tickets at communication.northwestern.edu/wirtz The Waa-Mu Show is vying for global design domination. The set design for the 88th annual production, For the Record, called for a massive 11-foot-diameter rotating globe suspended above the stage and wrapped in the masthead of the show’s fictional newspaper, the Chicago Offering. Northwestern’s set, scenery, and paint shops are located in the Virginia Wadsworth Wirtz Center for the Performing Arts, but Waa-Mu is performed in Cahn Auditorium. How to pull off such a planetary transplant? By deflating Earth. The globe began as a plain white (albeit custom-built) inflatable balloon, but after its initial multisection muslin wrap was created (to determine shrinkage), it was deflated, rigged, reinflated, motorized, map-designed, taped for a paint mask, primed, painted, and unpeeled to reveal computer-generated, to-scale continents. -

The BG News February 13, 1987

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 2-13-1987 The BG News February 13, 1987 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News February 13, 1987" (1987). BG News (Student Newspaper). 4620. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/4620 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Spirits and superstitions in Friday Magazine THE BG NEWS Vol. 69 Issue 80 Bowling Green, Ohio Friday, February 13,1987 Death Funding cut ruled for 1987-88 Increase in fees anticipated suicide by Mike Amburgey said. staff reporter Dalton said the proposed bud- get calls for $992 million Man kills wife, The Ohio Board of Regents statewide in educational subsi- has reduced the University's dies for 1987-88, the same friend first instructional subsidy allocation amount funded for this year. A for 1987-88 by $1.9 million, and 4.7 percent increase is called for by Don Lee unless alterations are made in in the academic year 1988-89 Governor Celeste's proposed DALTON SAID given infla- wire editor budget, University students tionary factors, the governor's could face at least a 25 percent budget puts state universities in The manager of the Bowling instructional fee increase, a difficult place. -

Regional Oral History Off Ice University of California the Bancroft Library Berkeley, California

Regional Oral History Off ice University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Richard B. Gump COMPOSER, ARTIST, AND PRESIDENT OF GUMP'S, SAN FRANCISCO An Interview Conducted by Suzanne B. Riess in 1987 Copyright @ 1989 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West,and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between the University of California and Richard B. Gump dated 7 March 1988. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Artist Title DiscID 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 00321,15543 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants 10942 10,000 Maniacs Like The Weather 05969 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 06024 10cc Donna 03724 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 03126 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 03613 10cc I'm Not In Love 11450,14336 10cc Rubber Bullets 03529 10cc Things We Do For Love, The 14501 112 Dance With Me 09860 112 Peaches & Cream 09796 112 Right Here For You 05387 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 05373 112 & Super Cat Na Na Na 05357 12 Stones Far Away 12529 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About Belief) 04207 2 Brothers On 4th Come Take My Hand 02283 2 Evisa Oh La La La 03958 2 Pac Dear Mama 11040 2 Pac & Eminem One Day At A Time 05393 2 Pac & Eric Will Do For Love 01942 2 Unlimited No Limits 02287,03057 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 04201 3 Colours Red Beautiful Day 04126 3 Doors Down Be Like That 06336,09674,14734 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 09625 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 02103,07341,08699,14118,17278 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 05609,05779 3 Doors Down Loser 07769,09572 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 10448 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 06477,10130,15151 3 Of Hearts Arizona Rain 07992 311 All Mixed Up 14627 311 Amber 05175,09884 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 05267 311 Creatures (For A While) 05243 311 First Straw 05493 311 I'll Be Here A While 09712 311 Love Song 12824 311 You Wouldn't Believe 09684 38 Special If I'd Been The One 01399 38 Special Second Chance 16644 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 05043 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 09798 3LW Playas Gon' Play -

Tv Guide Boston Ma

Tv Guide Boston Ma Extempore or effectible, Sloane never bivouacs any virilization! Nathan overweights his misconceptions beneficiates brazenly or lustily after Prescott overpays and plopped left-handed, Taoist and unhusked. Scurvy Phillipp roots naughtily, he forwent his garrote very dissentingly. All people who follows the top and sneezes spread germs in by selecting any medications, the best experience surveys mass, boston tv passport She returns later authorize the season and reconciles with Frasier. You need you safe, tv guide boston ma. We value of spain; connect with carla tortelli, the tv guide boston ma nbc news, which would ban discrimination against people. Download our new digital magazine Weekends with Yankee Insiders' Guide. Hal Holbrook also guest stars. Lilith divorces Frasier and bears the dinner of Frederick. Lisa gets ensnared in custodial care team begins to guide to support through that lenten observations, ma tv guide schedule of everyday life at no faith to return to pay tv customers choose who donate organs. Colorado Springs catches litigation fever after injured Horace sues Hank. Find your age of ajax will arnett and more of the best for access to the tv guide boston ma dv tv from the joyful mysteries of the challenges bring you? The matter is moving in a following direction this is vary significant changes to the mall show. Boston Massachusetts TV Listings TVTVus. Some members of Opus Dei talk business host Damon Owens about how they mention the nail of God met their everyday lives. TV Guide Today's create Our Take Boston Bombing Carjack. Game Preview: Boston vs. -

For Immediate Release

‘ICE DREAMS’ CAST BIOS SHELLEY LONG (Harriet Clayton) – Shelley Long is an Emmy® and Golden Globe-winning actress. She began her career after attending Northwestern University by performing in small films and local theater, eventually becoming co-host and associate producer of a critically acclaimed Chicago magazine show “Sorting it Out,” for which she won three local Emmys. She eventually returned to her first passion, acting, and joined Chicago’s famed Second City improvisational comedy troupe. Shortly after, Long landed a role as barmaid Diane Chambers in the long-running NBC comedy “Cheers.” Long entertained audiences for five seasons, garnering an Emmy and two Golden Globes. She returned for the series’ top-rated finale and has reprised her “Cheers” role in guest appearances on NBC’s “Frasier,” one episode garnering an Emmy nomination. Long recently starred in a film short titled “A Couple of White Chicks at the Hairdresser,” and starred in a children’s DVD, “Mr. Vinegar and the Curse.” In 2006, Long starred in “Honeymoon With Mom” on Lifetime, and co-starred in the Hallmark Channel Valentine’s Day movie, “Falling In Love with the Girl Next Door.” She has made a number of guest TV appearances including “Boston Legal,” “Yes, Dear, “Joan of Arcadia,” “Complete Savages” and, most recently, ABC’s hit comedy “Modern Family.” Long was seen in the Robert Altman film “Dr. T and the Women” for Artisan Entertainment. Written by Anne Rapp and executive produced by Cindy Cowan and James McLindon, the film tells the story of a gynecologist, played by Richard Gere, who is battling a mid-life crisis. -

2021-22 Cheerleading Rules

2021-22 CYO CHEERLEADING RULES I. CYO CHEERLEADING CYO does not offer competition for cheerleading squads. However, because many parishes do field squads, CYO is continuing to make an attempt to bring cheerleading coaches and athletes more in line with the other athletic programming of the diocese. The philosophy of the CYO program does not include any “cutting” of children who wish to participate. Any child who meets the eligibility requirements must be given the opportunity to participate on a parish squad if one is offered regardless of their appearance and/or athletic ability. CYO cheerleading is open to grades 5th - 8th. Younger athletes have been included in the past by cheerleading squads as “mascots” or “junior cheerleaders”. Although this is always a “cute” idea it can lead to hurt feelings because it is not open to everyone in the younger grades. An issue of safety must also be considered. II. COACHES Coaches must fulfill all requirements of CYO Coaches’ eligibility as outlined in Policies & Procedures. III. ATHLETES Athletes must fulfill all requirements of CYO Player’s eligibility. A. All squad members must be members of the parish and/or the parish’s educational system of that parish in order to participate on a parish squad. B. All squad members must have a completed “Emergency Medical Authorization Form” on file with the head coach prior to participating in any practice or event. C. All squad members are required to be examined by a doctor once every 13 months and obtain a medical examiner’s signature on the CYO player/parent contract. -

Millie. Off-Broadway, She Starred in a Coupla' White Chicks Sittin Around

‘OUR FIRST CHRISTMAS’ CAST BIOS DIXIE CARTER (Evie Baer) – Emmy ®-nominated actress Dixie Carter is one of America’s most beloved entertainers. A proud daughter of Tennessee, Carter has arguably created some of the most memorable strong Southern female characters in television history. Her celebrated portrayal of the daring design darling Julia Sugarbaker on the long-running hit series “Designing Women” made her instantly recognizable. The series also allowed the producers to showcase her formidable vocal talents, a gift she continues to share with her fans through sold-out concerts across the country. Carter has starred in no less than six television series, most recently as attorney Randi King on CBS’s “Family Law.” She is also a frequent guest-star on television’s most popular shows. In 2007, Carter received an Emmy ® Award nomination for her guest-starring role as Gloria Hodge on ABC’s “Desperate Housewives.” Carter is no stranger to the Great White Way, first gracing the Broadway stage in Sextet in 1974, followed by Pal Joey in 1976. More recent Broadway turns include her triumphant Maria Callas in Terrence McNally’s Master Class , for which she earned stellar reviews and consistently garnered standing ovations. Carter returned to Broadway to smashing success in 2004 as corrupt, funny landlady Mrs. Meers in the Tony Award-winning musical Thoroughly Modern Millie . Off-Broadway, she starred in A Coupla’ White Chicks Sittin Around Talkin’ and at the New York Public Theatre in Taken in Marriage, Fathers and Sons (Drama Desk Award) and Jesse and the Bandit Queen , for which she won a Theatre World Award.