MISCELANEA 60.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

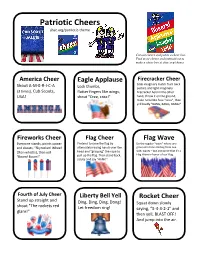

Patriotic Cheers Shac.Org/Patriotic-Theme

Patriotic Cheers shac.org/patriotic-theme Cut out cheers and put in a cheer box. Find more cheers and instructions to make a cheer box at shac.org/cheers. America Cheer Eagle Applause Firecracker Cheer Shout A-M-E-R-I-C-A Grab imaginary match from back Lock thumbs, pocket, and light imaginary (3 times), Cub Scouts, flutter fingers like wings, firecracker held in the other USA! shout "Cree, cree!" hand, throw it on the ground, make noise like fuse "sssss", then yell loudly "BANG, BANG, BANG!" Fireworks Cheer Flag Cheer Flag Wave Everyone stands, points upward Pretend to raise the flag by Do the regular “wave” where one and shouts, “Skyrocket! Whee!” alternately raising hands over the group at a time starting from one (then whistle), then yell head and “grasping” the rope to side, waves – but announce that it’s a Flag Wave in honor of our Flag. “Boom! Boom!” pull up the flag. Then stand back, salute and say “Ahhh!” Fourth of July Cheer Liberty Bell Yell Rocket Cheer Stand up straight and Ding, Ding, Ding, Dong! Squat down slowly shout "The rockets red Let freedom ring! saying, “5-4-3-2-1” and glare!" then yell, BLAST OFF! And jump into the air. Patriotic Cheer Mount New Citizen Cheer To recognize the hard work of Shout “U.S.A!” and thrust hand learning in order to pass the test with doubled up fist skyward Rushmore Cheer to become a new citizen, have while shouting “Hooray for the Washington, Jefferson, everyone stand, make a salute, Red, White and Blue!” Lincoln, Roosevelt! and say “We salute you!” Soldier Cheer Statue of Liberty USA-BSA Cheer Stand at attention and Cheer One group yells, “USA!” The salute. -

Oktoberfest’ Comes Across the Pond

Friday, October 5, 2012 | he Torch [culture] 13 ‘Oktoberfest’ comes across the pond Kaesespaetzle and Brezeln as they Traditional German listened to traditional German celebration attended music. A presentation with a slideshow was also given presenting by international, facts about German history and culture. American students One of the facts mentioned in the presentation was that Germans Thomas Dixon who are learning English read Torch Staff Writer Shakespeare because Shakespearian English is very close to German. On Friday, Sept. 28, Valparaiso Sophomore David Rojas Martinez University students enjoyed expressed incredulity at this an American edition of a famous particular fact, adding that this was German festival when the Valparaiso something he hadn’t known before. International Student Association “I learned new things I didn’t and the German know about Club put on German and Oktoberfest. I thought it was English,” Rojas he event great. Good food, Martinez said. was based on the good people, great “And I enjoyed annual German German culture. the food – the c e l e b r a t i o n food was great.” O k t o b e r f e s t , Other facts Ian Roseen Matthew Libersky / The Torch the largest beer about Germany Students from the VU German Club present a slideshow at Friday’s Oktoberfest celebration in the Gandhi-King Center. festival in the Senior mentioned in world. he largest the presentation event, which takes place in included the existence of the Munich, Germany, coincided with Weisswurstaequator, a line dividing to get into the German culture. We c u ltu re .” to have that mix and actual cultural VU’s own festival and will Germany into separate linguistic try to do things that have to do with Finegan also expressed exchange,” Finegan said. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

City of Charleston Municipal Court

City of Charleston Municipal Court 9/24/2021 Page 1 Officer Court Events - Monday, September 27, 2021 to Friday, October 29, 2021 Excludes Motions, Deferrals, and Jury Trials Adams Christopher Tuesday, October 19, 2021 20210416019558 8:30 am Criminal Bench Trial Manucy, Majorie Disorderly Conduct Katelyn Tuesday, October 12, 2021 20210416028112 9:30 am Criminal Bench Trial Thompson, Peter Shoplifting <= $2,000 - 16 - 13-0110(A) Akins Nicholas Friday, October 1, 2021 20210415996197 8:30 am Criminal Bench Trial Rowland, Kelsi Driving Under Influence 1st Offense . No BA Thursday, October 14, 2021 20210415968789 8:30 am Traffic Bench Trial Steed, Terrell DUS, license not suspended for DUI - 1st offense (56-01-0460)(A)(1)(a) 20210416020632 8:30 am Traffic Bench Trial Hurst, Louis Driving Under Influence 1st Offense . No BA 9/24/2021 Page 2 Officer Court Events - Monday, September 27, 2021 to Friday, October 29, 2021 Excludes Motions, Deferrals, and Jury Trials Akins Nicholas Thursday, October 14, 2021 20210416023954 8:30 am Traffic Bench Trial Connolly, Colin Operating vehicle w/o reg and license due to delinquency - 56-03-0840 20210416024511 8:30 am Traffic Bench Trial Marsh, Joshua Driving Under Influence 1st Offense . No BA 8102P0769552 8:30 am Traffic Bench Trial Simmons, Jamaul DUS, license not suspended for DUI - 1st offense (56-01-0460)(A)(1)(a) Friday, October 15, 2021 20210415961061 8:30 am Criminal Bench Trial-GATEWAY INCOMPLETE Gardo, Joshua Public Drunk 20210416024512 8:30 am Criminal Bench Trial Lowe, Zackary Malicious Injury to animals, personal property, injury value $2,000 or less 20210416024513 8:30 am Criminal Bench Trial Lowe, Zackary Careless Driving Monday, October 18, 2021 20210415989747 9:00 am DUI Pre-Trial Hearing Rotibi, Katari Driving Under Influence >= .10% <.16% with BA 56-05-2930(B) 20210416013897 9:00 am DUI Pre-Trial Hearing McClelland, Bradley Driving Under Influence 1st Offense . -

Frasier Global Mentorship Program

Frasier Global Mentorship Program Mentor Profile Originally from New Zealand, now based in Hawaii (married to US retired airforce officer and JAG Keric Chin with a 16 year old son, Mitchell). Economist and diplomat by training. Attended the University of Otago, NZ (my hometown) and then won an East-West Center scholarship to study in Hawaii. Blessed to have had a very varied international career, from the Central Bank of Iceland, the OECD in Paris to the NZ Foreign Ministry (last roles Deputy Secretary International Development and Ambassador to the United Nations Geneva), finance (Westpac Meet Amanda Ellis Banking Corp; co-founder Global Banking Alliance for Women), international development (ran NZAID, World Bank – started the Executive Director Hawaii and Asia- Women, Business and the Law project and first lines of credit for Pacific, ASU Julie Ann Wrigley Global women entrepreneurs in Africa). Institute of Sustainability. Passionate about sustainability policy and implementation and Find Me: women’s empowerment.Now Executive Director Hawaii and Asia Amanda Ellis on Linked In Pacific, ASU Julie Ann Wrigley Global Institute of Sustainability which is my best role yet! We CAN save the world with ASU/GIOS Industry Expertise: international I am convinced! Serve on a number of boards based in Hawaii, development, sustainable development, including the Bishop Museum (the largest Pacific collection in the diplomacy, finance, women’s economic world and a research museum for both oceans and land based empowerment, policy, gender and species), Hawaii Green Growth, the Institute for Climate and growth, Peace, East West Center, as well as the UN Women’s Mentorship Expertise: Empowerment Principles and microfinance organization FINCA international opportunities, especially International. -

Blacks Reveal TV Loyalty

Page 1 1 of 1 DOCUMENT Advertising Age November 18, 1991 Blacks reveal TV loyalty SECTION: MEDIA; Media Works; Tracking Shares; Pg. 28 LENGTH: 537 words While overall ratings for the Big 3 networks continue to decline, a BBDO Worldwide analysis of data from Nielsen Media Research shows that blacks in the U.S. are watching network TV in record numbers. "Television Viewing Among Blacks" shows that TV viewing within black households is 48% higher than all other households. In 1990, black households viewed an average 69.8 hours of TV a week. Non-black households watched an average 47.1 hours. The three highest-rated prime-time series among black audiences are "A Different World," "The Cosby Show" and "Fresh Prince of Bel Air," Nielsen said. All are on NBC and all feature blacks. "Advertisers and marketers are mainly concerned with age and income, and not race," said Doug Alligood, VP-special markets at BBDO, New York. "Advertisers and marketers target shows that have a broader appeal and can generate a large viewing audience." Mr. Alligood said this can have significant implications for general-market advertisers that also need to reach blacks. "If you are running a general ad campaign, you will underdeliver black consumers," he said. "If you can offset that delivery with those shows that they watch heavily, you will get a small composition vs. the overall audience." Hit shows -- such as ABC's "Roseanne" and CBS' "Murphy Brown" and "Designing Women" -- had lower ratings with black audiences than with the general population because "there is very little recognition that blacks exist" in those shows. -

The West Wing Weekly Episode 1:05: “The Crackpots and These Women

The West Wing Weekly Episode 1:05: “The Crackpots and These Women” Guest: Eli Attie [West Wing Episode 1.05 excerpt] TOBY: It’s “throw open our office doors to people who want to discuss things that we could care less about” day. [end excerpt] [Intro Music] JOSH: Hi, you’re listening to The West Wing Weekly. My name is Joshua Malina. HRISHI: And I’m Hrishikesh Hirway. JOSH: We are here to discuss season one, episode five, “The Crackpots and These Women”. It originally aired on October 20th, 1999. This episode was written by Aaron Sorkin; it was directed by Anthony Drazan, who among other things directed the 1998 film version of David Rabe’s Hurlyburly, the play on which it was based having been mentioned in episode one of our podcast. We’re coming full circle. HRISHI: Our guest today is writer and producer Eli Attie. Eli joined the staff of The West Wing in its third season, but before his gig in fictional D.C. he worked as a political operative in the real White House, serving as a special assistant to President Bill Clinton, and then as Vice President Al Gore’s chief speechwriter. He’s also written for Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, House, and Rosewood. Eli, welcome to The West Wing Weekly. ELI: It’s a great pleasure to be here. JOSH: I’m a little bit under the weather, but Lady Podcast is a cruel mistress, and she waits for no man’s cold, so if I sound congested, it’s because I’m congested. -

UC Berkeley Berkeley Planning Journal

UC Berkeley Berkeley Planning Journal Title Economics, Environment, and Equity: Policy Integration During Development in Vietnam Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3p999463 Journal Berkeley Planning Journal, 10(1) ISSN 1047-5192 Author O'Rourke, Dara Publication Date 1995 DOI 10.5070/BP310113059 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ECONOMICS, ENVIRONMENT, AND EQUITY Policy Integration During Development in Vietnam Dara O'Rourke Conflicts between economic development, environmental protection and social equity underlie efforts to promote •sustainable development. • The author proposes a simplified framework for integrating economic, environmental, and social policies in order to foster development that is ecologically and socially more sustainable. The paper analyzes the specific forms these policy areas are assuming in Vietnam, and the underlying political forces (both internal and external) driving policy implementation. An examination of how these policies are currently integrated and balanced follows. The analysis shows that contrary to government pronouncements, development patterns are unlikely to be altered toward more sustainable ends under existing institutions and laws. Finally, the article discusses the potential for integrating current policies to achieve sustainability goals. Introduction and Background The challenge of "sustainable development" is to overcome conflicts between economic development, environmental protection, and social equity concerns. This paper presents a case study of one country's attempts to integrate and balance policy objectives that promote sustainable development. Changes underway in Vietnam, while unique in many ways, are relevant to other developing countries attempting to industrialize while competing in the global economy. Vietnam's transition to a market economy is driven by global political-economic changes as well as internal demands for economic development. -

2021-22 Cheerleading Rules

2021-22 CYO CHEERLEADING RULES I. CYO CHEERLEADING CYO does not offer competition for cheerleading squads. However, because many parishes do field squads, CYO is continuing to make an attempt to bring cheerleading coaches and athletes more in line with the other athletic programming of the diocese. The philosophy of the CYO program does not include any “cutting” of children who wish to participate. Any child who meets the eligibility requirements must be given the opportunity to participate on a parish squad if one is offered regardless of their appearance and/or athletic ability. CYO cheerleading is open to grades 5th - 8th. Younger athletes have been included in the past by cheerleading squads as “mascots” or “junior cheerleaders”. Although this is always a “cute” idea it can lead to hurt feelings because it is not open to everyone in the younger grades. An issue of safety must also be considered. II. COACHES Coaches must fulfill all requirements of CYO Coaches’ eligibility as outlined in Policies & Procedures. III. ATHLETES Athletes must fulfill all requirements of CYO Player’s eligibility. A. All squad members must be members of the parish and/or the parish’s educational system of that parish in order to participate on a parish squad. B. All squad members must have a completed “Emergency Medical Authorization Form” on file with the head coach prior to participating in any practice or event. C. All squad members are required to be examined by a doctor once every 13 months and obtain a medical examiner’s signature on the CYO player/parent contract. -

IN the COURT of APPEALS of IOWA No. 15-0533 Filed June 15

IN THE COURT OF APPEALS OF IOWA No. 15-0533 Filed June 15, 2016 STEVEN EARL FRASIER, Applicant-Appellant, vs. STATE OF IOWA, Respondent-Appellee. ________________________________________________________________ Appeal from the Iowa District Court for Woodbury County, Edward A. Jacobson, Judge. Steven Frasier appeals from the dismissal of his fourth application for postconviction relief. AFFIRMED. Zachary S. Hindman of Bikakis, Mayne, Arneson, Hindman & Hisey, Sioux City, for appellant. Thomas J. Miller, Attorney General, and Sharon K. Hall, Assistant Attorney General, for appellee State. Considered by Danilson, C.J., and Vogel and Potterfield, JJ. 2 DANILSON, Chief Judge. Steven Frasier appeals from the dismissal of his fourth application for postconviction relief (PCR). Because the application was time barred, we affirm. The standard of review on appeal from the denial of a postconviction relief application, including summary judgment dismissals, is for errors of law. Castro v. State, 795 N.W.2d 789, 792 (Iowa 2011). Postconviction proceedings that raise constitutional issues are reviewed de novo. Ledezma v. State, 626 N.W.2d 134, 141 (Iowa 2001). On August 31, 1986, Steven Frasier, Simon Tunstall, and James Simpson were each charged with murder and burglary stemming from the shooting death of Jeffrey Jones in Sioux City, Iowa. Each defendant pled not guilty and proceeded to a joint trial in the Iowa District Court for Woodbury County. In February 1987, a jury convicted Frasier of first-degree murder and first-degree burglary. The jury also found that Frasier had a firearm during the commission of the offenses. On March 30, 1987, the district court denied Frasier’s post-trial motions and sentenced him to life imprisonment on the murder conviction and a term of imprisonment not to exceed twenty-five years on the burglary conviction, with the sentences to be served concurrently. -

Paramount Collection

Paramount Collection Airtight To control the air is to rule the world. Nuclear testing has fractured the Earth's crust, releasing poisonous gases into the atmosphere. Breathable air is now an expensive and rare commodity. A few cities have survived by constructing colossal air stacks which reach through the toxic layer to the remaining pocket of precious air above. The air is pumped into a huge underground labyrinth system, where a series of pipes to the surface feed the neighborhoods of the sealed city. It is the Air Force, known as the "tunnel hunters", that polices the system. Professor Randolph Escher has made a breakthrough in a top-secret project, the extraction of oxygen from salt water in quantity enough to return breathable air to the world. Escher is kidnapped by business tycoon Ed Conrad, who hopes to monopolize the secret process and make a fortune selling the air by subscription to the masses. Because Conrad Industries controls the air stacks, not subscribing to his "air service" would mean certain death. When Air Force Team Leader Flyer Lucci is murdered, his son Rat Lucci soon uncovers Conrad's involvement in his father's death and in Escher's kidnapping. Rat must go after Conrad, not only to avenge his father's murder, but to rescue Escher and his secret process as well. The loyalties of Rat's Air Force colleagues are questionable, but Rat has no choice. Alone, if necessary, he must fight for humanity's right to breathe. Title Airtight Genre Action Category TV Movie Format two hours Starring Grayson McCouch, Andrew Farlane, Tasma Walton Directed by Ian Barry Produced by Produced by Airtight Productions Proprietary Ltd. -

City of Blue Springs, Missouri Press Release

CITY OF BLUE SPRINGS, MISSOURI PRESS RELEASE 903 W. Main Street, Blue Springs, MO 64015 P: 816.228.0110 F: 816.228.7592 www.bluespringsgov.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DATE: October 6, 2010 CONTACT: Kim Nakahodo, Communications Manager Phone: 816.655.0497, Cell: 816.651.6449 Email: [email protected] The Wall That Heals – Blue Springs event a success BLUE SPRINGS, Mo. – The Wall That Heals – Blue Springs event held in Pink Hill Park from September 30 – October 3 was a success. During the four exhibit days, over 50,000 people gathered in Pink Hill Park to remember loved ones, share their experiences with others and learn more about the Vietnam War era. The event registered over 2,000 Vietnam Veterans for their choice of a commemorative medal, lapel pin or patch to thank them for their service to our country. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs registered over 160 new veterans for benefits and the “Put a Face With a Name” campaign collected 123 photos during the event. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund collected $10,651.73 at The Wall That Heals – Blue Springs event, the highest amount collected in a host city to date. “Blue Springs was honored to host The Wall That Heals; we set a new standard by giving each Vietnam Veteran a Commemorative Medal. Thank you to the many sponsors and hundreds of volunteers who helped make this event possible,” said Blue Springs Mayor Carson Ross. “This event is near and dear to my heart, I served in Vietnam as a US Army Combat Infantryman from 1967-68.