Modern Traditions Contempora

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modern Traditions

Modern Traditions gast_moderne_traditionen.indb 1 16.02.2007 16:22:57 Uhr Klaus-Peter Gast Modern Traditions Contemporary Architecture in India Birkhäuser Basel · Boston · Berlin gast_moderne_traditionen.indb 3 16.02.2007 16:22:57 Uhr —Graphic Design Miriam Bussmann, Berlin —Lithography Licht+Tiefe, Berlin —CAD assistance Raphel Kalapurakkal, Cochin —Printing Freiburger Graphische Betriebe, Freiburg i. Br. This book is also available in a German language edition: ISBN 978-3-7643-7753-3 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at <http://dnb.ddb.de>. Library of Congress Control Number: 2007922517 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, re-use of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in other ways, and storage in data banks. For any kind of use, permission of the copyright owner must be obtained. © 2007 Birkhäuser Verlag AG Basel · Boston · Berlin P.O.Box 133, CH-4010 Basel, Switzerland Part of Springer Science+Business Media Printed on acid-free paper produced from chlorine-free pulp. TCF d Printed in Germany ISBN 978-3-7643-7754-0 987654321 www.birkhauser.ch gast_moderne_traditionen.indb 4 16.02.2007 16:22:58 Uhr Table of Contents 7 Foreword 15 The Waking Giant Raj Jadhav — — MODERN INDIAN CLASSICAL-MODERN -

Engineers India House, New Delhi

Engineers India House, New Delhi ngineers India House forms The aim was to create an aircondi part of the commercial dis tioned office space which would have the trict centre at Bhikaiji Cama least possible initial outlay and subse E Bazaar, New Delhi. Raj Re quently minimum running expense. The wal was awarded the first studies of existing offices of E.LL. re prize for this prestigious cen vealed that work spaces with a floor tre in a two stage competition organised depth of 24.6 metres between windows by the M.inistry of Works for the layout should be acceptable and reduce substan plan and architectural control for a 14 tially the energy loads. It was also decided hectares site, comprising 220,000 square to face larger parameter of the building metres of shops and offices. north-south and further use the structural Engineers India building is the first elements of the cores and floor overhangs major office to be constructed within the to create micro-climate. The end result is Project Dam discipline of Bhikaiji Cama Bazaar. It that the cost of airconditioning in E.LL. houses the administrative, design, building is about 50% of similar build Architect: Raj Rewal. draughting, financial and public relation ings in Delhi. Structure: Engineers India offices of a public sector organisation It may be said that the form of the Ltd. dealing in design consultancy for industry building is derived from the point of Builder: Tarapore & and technology in India and abroad. view of saving energy. The structural Company. The concept is based on four cores on cores are designed in such a manner that Architect & Urban Design the comers containing lifts, staircases and they also serve the dual purpose of cut Consultants: Raj Rewal Associates. -

Dosti Greater Thane Brochure

THE CITY OF HAPPINESS CITY OF HAPPINESS Site Address: Dosti Greater Thane, Near SS Hospital, Kalher Junction 421 302. T: +91 86577 03367 Corp. Address: Adrika Developers Pvt. Ltd., Lawrence & Mayo House, 1st Floor, 276, Dr. D. N. Road, Fort, Mumbai - 400 001 • www.dostirealty.com Dosti Greater Thane - Phase 1 project is registered under MahaRERA No. P51700024923 and is available on website - https://maharerait.mahaonline.gov.in under registered projects Disclosures: (1) The artist’s impressions and stock image are used for representation purpose only. (2) Furniture, fittings and fixtures as shown/displayed in the show flat are for the purpose of showcasing only and do not form part of actual standard amenities to be provided in the flat. The flats offered for sale are unfurnished and all the amenities proposed to be provided in the flat shall be incorporated in the Agreement for Sale. (3) The plans are tentative in nature and proposed but not yet sanctioned. The plans, when sanctioned, may vary from the plans shown herein. (4) Dosti Club Novo is a Private Club House. It may not be ready and available for use and enjoyment along with the completion of Dosti Greater Thane - Phase 1 as its construction may get completed at a later date. The right to admission, use and enjoyment of all or any of the facilities/amenities in the Dosti Club Novo is reserved by the Promoters and shall be subject to payment of such admission fees, annual charges and compliance of terms and conditions as may be specified from time to time by the Promoters. -

20130118104321Small366.Pdf

Contents PERFORMANCE REPORT 2006-7 Forward looking statement In this Annual Report we have disclosed forward-looking information to enable investors to comprehend our prospects and take informed investment decisions. This report and other statements that we 10 periodically make contain forward-looking Yesterday’s statements that set out anticipated results wisdom, based on the management’s plans and tomorrow’s assumptions. We have tried wherever products possible to identify such statements by using words such as ‘anticipate’, Why does a nation of 1.1 billion ‘estimate’, ‘expects’, ‘projects’, ‘intends’, Cover story 30 consumers trust Emami? ‘plans’, ‘believes’, and words of similar substance in connection with any India’s FMCG success Wealth at discussion of future performance. story and Emami 18 the bottom of 26 Readers should bear in mind that we the pyramid cannot guarantee that these forward- looking statements will be realised, although we believe we have been prudent in our assumptions. The achievement of 12 results is subject to risks, uncertainties and The fame game: why brands estimates taken as assumptions. Should need celebrities known or unknown risks or uncertainties materialise, or should underlying Enhancing returns, Indian realty sector: assumptions prove inaccurate, actual 40 creating wealth 42 Gaining visibility results could vary materially from those anticipated, estimated or projected. 28 Emami and its global footprint 05 Inauguration of the new corporate office Also Opinions. Appreciation 02 Emami as a Group 46 -

ARCHITECTURE the ART & TECHNIQUE of DESIGNING and BUILDING Architecture Course Review Course Review Architecture

CAREERS360 YOUR QUICK GUIDE TO A COURSE IN ARCHITECTURE THE ART & TECHNIQUE OF DESIGNING AND BUILDING Architecture Course Review Course Review Architecture CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1. Introduction 03 ARCHITECTURE INVOLVES MAKING AN IDEA INTO A PROPOSAL OF 2. Eligibility Norms 05 A BUILT ENVIRONMENT, READY FOR EXECUTION. A BACHELOR’S IN ARCHITECTURE HELPS YOU LEARN HOW TO CONCEPTUALISE AND 3. Selecting an Institute 07 DESIGN BUILDINGS 4. Course Content 09 5. What after Graduation? 11 don’t think I even start with any precon- 6. Professional Talk 11 “ ceived ideas - the real inspiration comes 7. International Appeal of the Course 16 I from the person and the place and the 8. First Person 17 function to which they want to put the building to.” Laurie Baker, architect and father of ‘low- 9. Industry Talk 19 cost’ housing in India (1917-2007). 10. Select Institutes offering B.Arch in India 22 Buildings for homes, offices and shopping malls 11. Select institutes offering PG courses in Architecture 22 are the outcomes of hard work put in by archi- 12. Select institutions abroad 23 tects. Architecture is not just confined to erecting FAST FACTS Programme B.Arch Duration Five a structure. It encompasses considerations like years Eligibility 10+2 with PCM Entrances JEE Main, NATA Fee Rs. weather, cultural and economic factors. 31,300 per annum at SPA, New Project Editors Dr. Nimesh Chandra, S. Rajaram Delhi; Rs. 9. 99 lakhs for five years at BIT, Mesra Best Bachelor’s Research Shiphony Pavitran Suri, Prerna Singh With ample opportunities for specialisation institutes SPA, New Delhi; Sir J.J. -

'Indian Architecture' and the Production of a Postcolonial

‘Indian Architecture’ and the Production of a Postcolonial Discourse: A Study of Architecture + Design (1984-1992) Shaji K. Panicker B. Arch (Baroda, India), M. Arch (Newcastle, Australia) A Thesis Submitted to the University of Adelaide in fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Architecture, Landscape Architecture and Urban Design Centre for Asian and Middle Eastern Architecture 2008 Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................................................iv Declaration ............................................................................................................................................................................................vi Acknowledgements..........................................................................................................................................................................vii List of Figures ........................................................................................................................................................................................ ix 1 Introduction ........................................................................................... 1 1.1: Overview..................................................................................................................................................................1 1.2: Background...........................................................................................................................................................2 -

Annual Report English 2015-16 Cover

ANNUAL REPORT 2015-16 SCHOOL OF PLANNING AND ARCHITECTURE An “Institution of National Importance” under an Act of Parliament (Ministry of HRD, Government of India) Indraprastha Estate, New Delhi - 110002 PREFACE School of Planning and Architecture (SPA) New Delhi is an Institution of National Importance under an Act of Parliament, Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India since January 2015. Prior to becoming an institution of national importance, SPA New Delhi has roots in the Department of Architecture, which was founded in 1942 as a part of Delhi School of Polytechnic. Department of Architecture subsequently merged with the School of Town and Country Planning and became SPA in 1959. SPA New Delhi was given the status of Deemed to be University in 1979. The School offers two undergraduate programmes, one for architecture and the other in physical planning and 10 postgraduate programmes, three in architecture, five in planning, and one each in industrial design and building engineering and management. Total strength of the students in session 2015-2016 was 1,189 of which 717 were undergraduate students. Presently 44 students are pursuing Ph.D. programme in the School. Apart from imparting professional education in various fields related to build environment, the School has also been pursuing sponsored research from various government bodies and institutions throughout India. The School also carries out capacity building activities in the form of Quality Improvement Programmes and training workshops in collaboration with other institutions. This Annual Report covers the activities and achievements of the various departments of studies and their respective members during 2015-16. -

Ar. Hafeez Contractor.Cdr

feed PUNE FEED FORUM FOR EXCHANGE AND EXCELLENCE IN DESIGN Presents “WORKS OF HAFEEZ CONTRACTOR” by Ar. Hafeez Contractor Mumbai, India Cyber City-Mauritius Infosys Progeon-Bangalore Megh Malhar & Raag-Mumbai Infosys-Pune ICAI-Bandra Kurla Complex-Mumbai Queen's Court-Worli-Mumbai Private Residence, New Delhi Gyanodaya-Navi Mumbai Mahagun-Ghaziabad The Osho Commune-Pune H.V.Eye Hospital-Pune Hafeez Contractor was born in 1950. He did his Graduate Diploma in architecture from Mumbai in 1975 and completed his graduation from Columbia University New York (USA) on Tata Scholarship. Hafeez Contractor commenced his career in 1968 with T. Khareghat as an Apprentice Architect in 1977. He became the associate partner in the same firm. It was in 1982 that he began with his own private practice. Between 1977 and 1980 Hafeez has been a visiting faculty at the Academy of Architecture, Mumbai. He is a member of the Bombay Heritage Committee and New Delhi Lutyens Bungalow Zone Review Committee. His practice had modest beginnings in 1982 with a staff of two. Today the firm has over 350 employees including senior associates, architects, interior designers, draftsmen, civil engineering team and architectural support staff. The firm has conceptualized, designed and executed a wide range of architectural projects like bungalows, residential developments, hospitals, hotels, corporate offices, banking and financial institutions, commercial complexes, shopping malls, educational institutions, recreational and sports facilities, townships, airports, railway stations, urban planning and civic redevelopment projects. The market influences his work to a great extent. While he insist his work has no one style, each project requiring widely different treatment, is the underlying balance of form and function that explains, to a great extent, his success. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Aga Khan Aga Khan Aga Khan Prize-Winning Award for Award for Award for Projects Architecture Architecture Architecture 2019 2019 2019 The Aga Khan Award for Architecture THROUGH ITS EFFORTS, the Award seeks to identify Steering Committee Master Jury 122 Prize-Winning Projects in 14 Award Cycles (1980-2019): is given every three years to projects and encourage building concepts that successfully address the needs and aspirations of societies 67 in Asia that set new standards of excellence across the world, in which Muslims have a significant 32 in Africa in architecture, planning practices, presence. 23 in Europe & Turkey historic preservation and landscape The selection process emphasizes architecture that not only provides for people’s physical, social His Highness the Aga Khan TURKEY CYPRUS Nail Cakirhan Residence, Akaya Village Rehabilitation of the Walled City, Nicosia architecture. and economic needs, but that also stimulates and Turkish Historical Society, Ankara Chairman Mosque of the Grand National Assembly, Ankara LEBANON Middle East Technical University, Ankara Samir Kassir Square, Beirut responds to their cultural expectations. Particular Olbia Social Centre, Antalya Great Omari Mosque, Sidon B2 Cakirhan Residence Issam Fares Institute, Beirut attention is given to building schemes that use local Ertegun House, Bodrum JORDAN Demir Holiday Village, Bodrum East Wahdat Upgrading Programme, Amman Sir David Adjaye Azim Nanji Anthony Kwamé Edhem Eldem Gurel Family Summer Residence, Canakkale resources and appropriate technology in innovative SOS Children’s Village, Aqaba Rustem Pasa Caravanserai, Edirne ways, and to projects likely to inspire similar efforts Principal, Adjaye Special Advisor, Appiah Collège de France Ipekyol Textile Factory, Edirne SAUDI ARABIA Social Security Complex, Istanbul Hajj Terminal, King Abdul Azis Intl Airport, Jeddah elsewhere. -

POST INDEPENDENCE ARCHITECTURE in INDIA : a Search for Identity in Modernism

© 2018 JETIR July 2018, Volume 5, Issue 7 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) POST INDEPENDENCE ARCHITECTURE IN INDIA : A Search For Identity in Modernism Ms. Sofia Sebastian, Mr. Ravishankar K.R. University of Nizwa Sultanate of Oman ABSTRACT-India had a glorious history in terms of its rich art and architecture, starting from 3000 B.C.During the British period from 1615- 1947, the major cities of Delhi, Calcutta, Mumbai and Chennai were highlighted with rich colonial styles of Indo-Sarcenic architecture. After Independence, there was a boom of building activities and there were confusions and debates on the style of architecture to be followed– modernism or historicism. Different styles of Modernism evolved raising the question of Identityin Post Independent architecture. KEYWORDS-Modernism, Post-Independence, Revivalism, geometric forms, Expressionist style, biomimicry architecture, contemporary modernism, chattris, progressive architecture, Brutalism, Regionalism, Tradition, Vastu Purusha Mandala, metamorphosis, identity, climate responsive, vernacular ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY OF INDIA India has a rich history dating from 3000 B.C. Indus Valley Civilization to 1947 AD Indo-Sarcenic Architecture. The main historical period and styles are as follows. The Indus Valley Civilization 3000-1700 BC The Indus Valley Civilization dates to 3000-1700 BC with towns of Mohenjodaroand Harappa with a good town planning system and an elaborate drainage system (brick lined drainage on all the street sides). Post MahaJanapada Period 600 BC-200AD This period architecture ranges from Buddhist stupa, Viharas, temples (brick and wood), rock cut architecture, Ajanta and Ellora, step wells, etc Figure 1: Sanchi Stupa Middle ages 200 -1500 AD The Middle Ages architecture speaks of sculptured temples both South India temples and North India temples. -

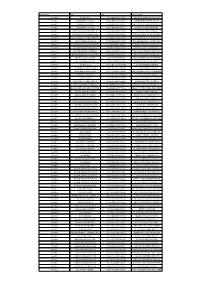

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 01600009 GHOSH JAYA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 01600009 GHOSH JAYA U72200WB2005PTC104166 ANI INFOGEN PRIVATE LIMITED 01600031 KISHORE RAJ YADAV U24230BR1991PTC004567 RENHART HEALTH PRODUCTS 01600031 KISHORE RAJ YADAV U00800BR1996PTC007074 ZINNA CAPITAL & SAVING PRIVATE 01600031 KISHORE RAJ YADAV U00365BR1996PTC007166 RAWATI COMMUNICATIONS 01600058 ARORA KEWAL KUMAR RITESH U80301MH2008PTC188483 YUKTI TUTORIALS PRIVATE 01600063 KARAMSHI NATVARLAL PATEL U24299GJ1966PTC001427 GUJARAT PHENOLIC SYNTHETICS 01600094 BUTY PRAFULLA SHREEKRISHNA U91110MH1951NPL010250 MAHARAJ BAG CLUB LIMITED 01600095 MANJU MEHTA PRAKASH U72900MH2000PTC129585 POLYESTER INDIA.COM PRIVATE 01600118 CHANDRASHEKAR SOMASHEKAR U55100KA2007PTC044687 COORG HOSPITALITIES PRIVATE 01600119 JAIN NIRMALKUMAR RIKHRAJ U00269PN2006PTC022256 MAHALAXMI TEX-CLOTHING 01600119 JAIN NIRMALKUMAR RIKHRAJ U29299PN2007PTC130995 INNOVATIVE PRECITECH PRIVATE 01600126 DEEPCHAND MEHTA VALCHAND U52393MH2007PTC169677 DEEPSONS JEWELLERS PRIVATE 01600133 KESARA MANILAL PATEL U24299GJ1966PTC001427 GUJARAT PHENOLIC SYNTHETICS 01600141 JAIN REKHRAJ SHIVRAJ U00269PN2006PTC022256 MAHALAXMI TEX-CLOTHING 01600144 SUNITA TULI U65993DL1991PLC042580 TULI INVESTMENT LIMITED 01600152 KHANNA KUMAR SHYAM U65993DL1991PLC042580 TULI INVESTMENT LIMITED 01600158 MOHAMED AFZAL FAYAZ U51494TN2005PTC056219 FIDA FILAMENTS PRIVATE LIMITED 01600160 CHANDER RAMESH TULI U65993DL1991PLC042580 TULI INVESTMENT LIMITED 01600169 JUNEJA KAMIA U32109DL1999PTC099997 JUNEJA SALES PRIVATE LIMITED 01600182 NARAYANLAL SARDA SHARAD U00269PN2006PTC022256 -

Empanelment of Consultants (Pmc) for Mumbai Region (New)

EMPANELMENT OF CONSULTANTS (PMC) FOR MUMBAI REGION (NEW) Manpower Works Exp. Yearly Turnover Average Annual Team Leader Office space (Area) in Year of Total Marks Sr.No. Name of Firm and Address 2013-14 2014-15 2015-16 Turnover in Rs. Grade Remark (Name & Qualification) Sq.m Establishment Mass High Special Government PHC General Obtained Architect Engineer In Rs. In Rs. In Rs. (Lakhs) Housing Rise Work Work Works Works (Lakhs) (Lakhs) (Lakhs) (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) Mumbai Region Design Ideas Registered Office-74.32 Mr. Paresh Padgaonkar 1, Girija Bhuvan, 163/B, Ground Floor, Opp. Branch Office (pune)- B.Arch 1 Parsi Gymkhana, Dr. B.A. Road, Dadar (E), 41.80,work office- 2001 4 10 0 0 4 3 0 9 114.12542 118.4413 113.06032 115 Mrs. Aarti Padgaonkar 55 C - Mumbai 400 014. 46.45,Branch BAMS [email protected] office(Goa)-27.87 022-24118778 Marks Obtained 5 5 10 0 0 5 5 0 10 15 Pentacle Consultants (India) Pvt.Ltd. B/406, Pranik Chambers, Saki Vihar Road, 1. Mr.Mahendra More MBA(Oxford) 2 Saki Naka, Andheri (E), Mumbai 400072. 232.257 1982 6 14 0 11 7 4 0 5 481.42108 644.89848 648.7934 592 [email protected], 2. Mr.Ganesh More 70 B - [email protected] B.E.(Civil) 02266952533 / 44 9920290210 Marks Obtained 5 10 10 0 10 5 5 0 10 15 Worksphere Ventures (India) Head Office:-1850,Pune- Pvt.Ltd. Mr.Swapnil Sawant 3 50,Nasik-52,Nagpur- 2003 3 3 0 0 3 3 0 5 766.13899 148.84219 205.4638 373 407-414, Exim Link, Opp.