Der Baader-Meinhof Komplex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Casting Directors Network Index

International Casting Directors Network Index 01 Welcome 02 About the ICDN 04 Index of Profiles 06 Profiles of Casting Directors 76 About European Film Promotion 78 Imprint 79 ICDN Membership Application form Gut instinct and hours of research “A great film can feel a lot like a fantastic dinner party. Actors mingle and clash in the best possible lighting, and conversation is fraught with wit and emotion. The director usually gets the bulk of the credit. But before he or she can play the consummate host, someone must carefully select the right guests, send out the invites, and keep track of the RSVPs”. ‘OSCARS: The Role Of Casting Director’ by Monica Corcoran Harel, The Deadline Team, December 6, 2012 Playing one of the key roles in creating that successful “dinner” is the Casting Director, but someone who is often over-looked in the recognition department. Everyone sees the actor at work, but very few people see the hours of research, the intrinsic skills, the gut instinct that the Casting Director puts into finding just the right person for just the right role. It’s a mix of routine and inspiration which brings the characters we come to love, and sometimes to hate, to the big screen. The Casting Director’s delicate work as liaison between director, actors, their agent/manager and the studio/network figures prominently in decisions which can make or break a project. It’s a job that can't garner an Oscar, but its mighty importance is always felt behind the scenes. In July 2013, the Academy of Motion Pictures of Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) created a new branch for Casting Directors, and we are thrilled that a number of members of the International Casting Directors Network are amongst the first Casting Directors invited into the Academy. -

Review of Sarah Colvin. Ulrike Meinhof and West German Terrorism: Language, Violence, and Identity

Xavier University Exhibit Faculty Scholarship Modern Languages 5-2011 Review of Sarah Colvin. Ulrike Meinhof and West German Terrorism: Language, Violence, and Identity. Rochester: Camden House, 2009. Jamie Trnka Follow this and additional works at: https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/modern_languages_faculty Recommended Citation Trnka, Jamie, "Review of Sarah Colvin. Ulrike Meinhof and West German Terrorism: Language, Violence, and Identity. Rochester: Camden House, 2009." (2011). Faculty Scholarship. 5. https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/modern_languages_faculty/5 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Modern Languages at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. German Studies Association Review Reviewed Work(s): Ulrike Meinhof and West German Terrorism: Language, Violence, and Identity by Sarah Colvin Review by: JAMIE H. TRNKA Source: German Studies Review, Vol. 34, No. 2 (May 2011), pp. 468-469 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press on behalf of the German Studies Association Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41303778 Accessed: 25-11-2019 15:56 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. -

Revisiting Zero Hour 1945

REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER VOLUME 1 American Institute for Contemporary German Studies The Johns Hopkins University REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER HUMANITIES PROGRAM REPORT VOLUME 1 The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies. ©1996 by the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies ISBN 0-941441-15-1 This Humanities Program Volume is made possible by the Harry & Helen Gray Humanities Program. Additional copies are available for $5.00 to cover postage and handling from the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, Suite 420, 1400 16th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036-2217. Telephone 202/332-9312, Fax 202/265- 9531, E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.aicgs.org ii F O R E W O R D Since its inception, AICGS has incorporated the study of German literature and culture as a part of its mandate to help provide a comprehensive understanding of contemporary Germany. The nature of Germany’s past and present requires nothing less than an interdisciplinary approach to the analysis of German society and culture. Within its research and public affairs programs, the analysis of Germany’s intellectual and cultural traditions and debates has always been central to the Institute’s work. At the time the Berlin Wall was about to fall, the Institute was awarded a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to help create an endowment for its humanities programs. -

Conceptions of Terror(Ism) and the “Other” During The

CONCEPTIONS OF TERROR(ISM) AND THE “OTHER” DURING THE EARLY YEARS OF THE RED ARMY FACTION by ALICE KATHERINE GATES B.A. University of Montana, 2007 B.S. University of Montana, 2007 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures 2012 This thesis entitled: Conceptions of Terror(ism) and the “Other” During the Early Years of the Red Army Faction written by Alice Katherine Gates has been approved for the Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures _____________________________________ Dr. Helmut Müller-Sievers _____________________________________ Dr. Patrick Greaney _____________________________________ Dr. Beverly Weber Date__________________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Gates, Alice Katherine (M.A., Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures) Conceptions of Terror(ism) and the “Other” During the Early Years of the Red Army Faction Thesis directed by Professor Helmut Müller-Sievers Although terrorism has existed for centuries, it continues to be extremely difficult to establish a comprehensive, cohesive definition – it is a monumental task that scholars, governments, and international organizations have yet to achieve. Integral to this concept is the variable and highly subjective distinction made by various parties between “good” and “evil,” “right” and “wrong,” “us” and “them.” This thesis examines these concepts as they relate to the actions and manifestos of the Red Army Faction (die Rote Armee Fraktion) in 1970s Germany, and seeks to understand how its members became regarded as terrorists. -

Through FILMS 70 Years of European History Through Films Is a Product in Erasmus+ Project „70 Years of European History 1945-2015”

through FILMS 70 years of European History through films is a product in Erasmus+ project „70 years of European History 1945-2015”. It was prepared by the teachers and students involved in the project – from: Greece, Czech Republic, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Turkey. It’ll be a teaching aid and the source of information about the recent European history. A DANGEROUS METHOD (2011) Director: David Cronenberg Writers: Christopher Hampton, Christopher Hampton Stars: Michael Fassbender, Keira Knightley, Viggo Mortensen Country: UK | GE | Canada | CH Genres: Biography | Drama | Romance | Thriller Trailer In the early twentieth century, Zurich-based Carl Jung is a follower in the new theories of psychoanalysis of Vienna-based Sigmund Freud, who states that all psychological problems are rooted in sex. Jung uses those theories for the first time as part of his treatment of Sabina Spielrein, a young Russian woman bro- ught to his care. She is obviously troubled despite her assertions that she is not crazy. Jung is able to uncover the reasons for Sa- bina’s psychological problems, she who is an aspiring physician herself. In this latter role, Jung employs her to work in his own research, which often includes him and his wife Emma as test subjects. Jung is eventually able to meet Freud himself, they, ba- sed on their enthusiasm, who develop a friendship driven by the- ir lengthy philosophical discussions on psychoanalysis. Actions by Jung based on his discussions with another patient, a fellow psychoanalyst named Otto Gross, lead to fundamental chan- ges in Jung’s relationships with Freud, Sabina and Emma. -

RAF) Die Herausforderung Für Das Bundeskriminalamt Als Zentrale Ermittlungsbehörde

60 Jahre Staatsschutz im Spannungsfeld zwischen Freiheit und Sicherheit Rote Armee Fraktion (RAF) Die Herausforderung für das Bundeskriminalamt als Zentrale Ermittlungsbehörde Günther Scheicher, Abteilungspräsident a.D. (BKA) - Es gilt das gesprochene Wort - 1. Einleitung: 60 Jahre Bundeskriminalamt, fast 30 Jahre Ermittlungen gegen die RAF – eine große, bis dahin die größte Herausforderung nicht nur für die Sicherheitsbehörden, sondern für alle gesellschaftlichen Kräfte unserer Republik, vielleicht vergleichbar mit der heute so relevanten Bedrohung durch den islamistischen Terrorismus. 2. Dimension in Fakten und Zahlen In ihrer 30jährigen Terrorgeschichte verübte die RAF ab Mai 1972 26 Anschläge mit verheerenden Folgen. 34 Menschen wurden von der RAF ermordet, und aus ihren Reihen fanden 20 Mitglieder den Tod. Mit dem Zeitraffer erinnere ich an 1972 mit den todbringenden Anschlägen auf Einrichtungen der US-Armee in Frankfurt und Heidelberg, an die Sprengstoffanschläge auf das Bayerische Landeskriminalamt, das Polizeipräsidium in Augsburg, das Springer- Hochhaus in Hamburg und auf den Ermittlungsrichter beim Bundesgerichtshof Buddenberg, dann 1975 an den Überfall auf die deutsche Botschaft in Stockholm, an das Jahr 1977 mit der Ermordung des Generalbundesanwaltes Buback, des Bankiers Ponto, des Arbeitgeberpräsidenten Schleyer, an die Morde und Sprengstoffanschläge der Jahre 1985 bis 1993, stellvertretend für die Opfer in dieser Zeit nenne ich aus dem Bereich des Wirtschaftslebens die Namen Zimmermann, Beckurts, Herrhausen, Rohwedder, aus der Politik von Braunmühl, Tietmeyer, Neusel. 2 Doch wir entsinnen uns nicht nur der bekannten Namen, sondern genauso der Toten und Verletzten aus unseren Reihen und denen der niederländischen Kollegen, und wir denken ebenso an die Soldaten der US-Army wie an ganz normale Menschen, die Opfer der RAF oder ihrer Verbündeten geworden sind. -

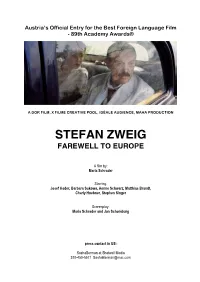

Stefan Zweig Farewell to Europe

Austria’s Official Entry for the Best Foreign Language Film - 89th Academy Awards® A DOR FILM, X FILME CREATIVE POOL, IDÉALE AUDIENCE, MAHA PRODUCTION STEFAN ZWEIG FAREWELL TO EUROPE A film by: Maria Schrader Starring: Josef Hader, Barbara Sukowa, Aenne Schwarz, Matthias Brandt, Charly Huebner, Stephen SInger Screenplay: Maria Schrader and Jan Schomburg press contact in US: SashaBerman at Shotwell Media 310-450-5571 [email protected] Table of Contents Short synopsis & press note …………………………………………………………………… 3 Cast ……............................................................................................................................ 4 Crew ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Long Synopsis …………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Persons Index…………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Interview with Maria Schrader ……………………………………………………………….... 17 Backround ………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 In front of the camera Josef Hader (Stefan Zweig)……………………………………...……………………………… 21 Barbara Sukowa (Friderike Zweig) ……………………………………………………………. 22 Aenne Schwarz (Lotte Zweig) …………………………….…………………………………… 23 Behind the camera Maria Schrader………………………………………….…………………………………………… 24 Jan Schomburg…………………………….………...……………………………………………….. 25 Danny Krausz ……………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Stefan Arndt …………..…………………………………………………………………….……… 27 Contacts……………..……………………………..………………………………………………… 28 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Technical details Austria/Germany/France, 2016 Running time 106 Minutes Aspect ratio 2,39:1 Audio format 5.1 ! 2! “Each one of us, even the smallest and the most insignificant, -

Bulletin of the GHI Washington

Bulletin of the GHI Washington Issue 43 Fall 2008 Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Stiftung Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. TERRORISM IN GERMANY: THE BAADER-MEINHOF PHENOMENON Lecture delivered at the GHI, June 5, 2008 Stefan Aust Editor-in-Chief, Der Spiegel, 1994–2008 Recently on Route 73 in Germany, between Stade und Cuxhaven, my phone rang. On the other end of the line was Thilo Thielke, SPIEGEL correspondent in Africa. He was calling on his satellite phone from Dar- fur. For two weeks he had been traveling with rebels in the back of a pick-up truck, between machine guns and Kalashnikovs. He took some- thing to read along for the long evenings: Moby Dick. He asked me: “How was that again with the code names? Who was Captain Ahab?” “Andreas Baader, of course,” I said and quoted Gudrun Ensslin from a letter to Ulrike Meinhof: “Ahab makes a great impression on his first appearance in Moby Dick . And if either by birth or by circumstance something pathological was at work deep in his nature, this did not detract from his dramatic character. For tragic greatness always derives from a morbid break with health, you can be sure of that.” “And the others?” the man from Africa asked, “Who was Starbuck?” At that time, that was not a coffee company—also named after Moby Dick—but the code name of Holger Meins. -

The Representation of Suicide in the Cinema

The Representation of Suicide in the Cinema John Saddington Submitted for the degree of PhD University of York Department of Sociology September 2010 Abstract This study examines representations of suicide in film. Based upon original research cataloguing 350 films it considers the ways in which suicide is portrayed and considers this in relation to gender conventions and cinematic traditions. The thesis is split into two sections, one which considers wider themes relating to suicide and film and a second which considers a number of exemplary films. Part I discusses the wider literature associated with scholarly approaches to the study of both suicide and gender. This is followed by quantitative analysis of the representation of suicide in films, allowing important trends to be identified, especially in relation to gender, changes over time and the method of suicide. In Part II, themes identified within the literature review and the data are explored further in relation to detailed exemplary film analyses. Six films have been chosen: Le Feu Fol/et (1963), Leaving Las Vegas (1995), The Killers (1946 and 1964), The Hustler (1961) and The Virgin Suicides (1999). These films are considered in three chapters which exemplify different ways that suicide is constructed. Chapters 4 and 5 explore the two categories that I have developed to differentiate the reasons why film characters commit suicide. These are Melancholic Suicide, which focuses on a fundamentally "internal" and often iII understood motivation, for example depression or long term illness; and Occasioned Suicide, where there is an "external" motivation for which the narrative provides apparently intelligible explanations, for instance where a character is seen to be in danger or to be suffering from feelings of guilt. -

The Munich Massacre

The Munich Massacre Munich, Germany Munich Olympic Headquarters September 4, 1972 7:00 pm Sunlight glittered on the West German flag, causing the bottom gold strip to shine almost as bright as the stars. Kathrin glanced up at the beauty of her country's flag and said a silent prayer in her head. Nine days ago the Olympic games had started and gone forward without a hitch. She and the rest of the Federal Republic of Germany could not help but feel a swell of proudness in their hearts as the games continued. For so long the world had gazed at them through the eyes of the deeds their parents and grandparents had committed more than 3o years ago. These games marked an opportunity to show the world that they were no longer the blood stricken country they had been in the past. They were a new Germany. Kathrin let her eyes roam the flag once more and the smile waivered on her face. The games were not over yet. She knew well enough the potential that destruction had and she refused to give it a foothold. Entering the Olympic Headquarter building, she brisked her way through security and into her office, where her appointment was already there waiting. “Good evening, Shmuel.” Kathrin said in a warm voice, that filled the room. She smiled and shook his hand. Earlier that day he had asked to meet with her, and by the tone of his voice Kathrin knew that this was not just another friendly visit . She expressed an attitude in which any hostess should have when the head of the Olympic Israeli delegation should ask to meet. -

American Auteur Cinema: the Last – Or First – Great Picture Show 37 Thomas Elsaesser

For many lovers of film, American cinema of the late 1960s and early 1970s – dubbed the New Hollywood – has remained a Golden Age. AND KING HORWATH PICTURE SHOW ELSAESSER, AMERICAN GREAT THE LAST As the old studio system gave way to a new gen- FILMFILM FFILMILM eration of American auteurs, directors such as Monte Hellman, Peter Bogdanovich, Bob Rafel- CULTURE CULTURE son, Martin Scorsese, but also Robert Altman, IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION James Toback, Terrence Malick and Barbara Loden helped create an independent cinema that gave America a different voice in the world and a dif- ferent vision to itself. The protests against the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement and feminism saw the emergence of an entirely dif- ferent political culture, reflected in movies that may not always have been successful with the mass public, but were soon recognized as audacious, creative and off-beat by the critics. Many of the films TheThe have subsequently become classics. The Last Great Picture Show brings together essays by scholars and writers who chart the changing evaluations of this American cinema of the 1970s, some- LaLastst Great Great times referred to as the decade of the lost generation, but now more and more also recognised as the first of several ‘New Hollywoods’, without which the cin- American ema of Francis Coppola, Steven Spiel- American berg, Robert Zemeckis, Tim Burton or Quentin Tarantino could not have come into being. PPictureicture NEWNEW HOLLYWOODHOLLYWOOD ISBN 90-5356-631-7 CINEMACINEMA ININ ShowShow EDITEDEDITED BY BY THETHE -

Ulrike Meinhof and the Red Army Faction

Ulrike Meinhof and the Red Army Faction Ulrike Meinhof and the Red Army Faction Performing Terrorism Leith Passmore ulrike meinhof and the red army faction: performing terrorism Copyright © Leith Passmore, 2011. Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2011 978-0-230-33747-3 All rights reserved. First published in 2011 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN® in the United States— a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Where this book is distributed in the UK, Europe, and the rest of the world, this is by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN 978-1-349-34096-5 ISBN 978-0-230-37077-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230370777 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Passmore, Leith, 1981– Ulrike Meinhof and the Red Army Faction : performing terrorism / Leith Passmore. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Meinhof, Ulrike Marie. 2. Women terrorists—Germany (West)— Biography. 3. Women journalists—Germany (West)—Biography. 4. Terrorism— Germany (West)—History. 5. Rote Armee Fraktion—History. I. Title. HV6433.G3P37 2011 363.325092—dc22 2011016072 A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library. Design by Scribe Inc. First edition: November 2011 Contents Acknowledgments vii Preface ix Introduction: Performing Terrorism 1 1 Where Words Fail 13 2 Writing Underground 33 3 The Art of Hunger 61 4 Show, Trial, and Error 83 5 SUICIDE = MURDER = SUICIDE 103 Conclusion: Voices and Echoes 119 Notes 127 Bibliography 183 Index 201 Acknowledgments This book is based largely on a rich archival source base.