Regional Oral History Office the Bancroft Library Robert Di Giorgio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

At a Glance Concert Schedule

At A Glance Concert Schedule SC- Supper Club CH- Concert Hall MB- Music Box Full Venue RT- Rooftop Deck RF- Riverfront Porch PDR- Private Dining Room Sun 4/23 CH Turning Point Church Presented by NEO Church Planting network Weekly Worship Service (View Page) Sun 4/23 SC BB King Brunch With Travis "The Moonchild" Haddix (View Page) Sun 4/23 CH Bob Mould Solo Electric Show with Hüsker Dü Frontman (Tickets) Wed 4/26 SC Topic: Cleveland Starts Here: History of Western Reserve Historical Society Storytellers: Kelly Falcone-Hall & Dennis Barrie Cleveland Stories Dinner Parties (View Page) Thu 4/27 SC Motown Night with Nitebridge Enjoy the jumpin' sounds of your favorite classic hits! (View Page) Thu 4/27 CH Dan Fogelberg Night with The Don Campbell Band (Tickets) Sun 4/30 CH Turning Point Church Presented by NEO Church Planting network Weekly Worship Service (View Page) Sun 4/30 SC Beatles Brunch With The Sunrise Jones (Tickets) Sun 4/30 SC Cleveland Songwriters Showcase Raymond Arthur Flanagan, Rebekah Jean, & Austin Stambaugh (View Page) Wed 5/3 SC Topic: Plans Made, Plans Changed: CLE’s Urban Design Storyteller: Chris Ronayne Cleveland Stories Dinner Parties (View Page) Thu 5/4 SC Rebels Without Applause One of Cleveland's Longtime Favorite Cover Bands Celebrating 35 Years! (View Page) Fri 5/5 CH Martin Barre of Jethro Tull Award-Winning Legendary Guitarist (Tickets) Fri 5/5 SC Tequila! Cinco de Mayo Party with Cats on Holiday Tequila Flights, Taco Features and more! (Tickets) Sat 5/6 SC Hey Mavis Northeast Ohio’s Favorite Americana Folk -

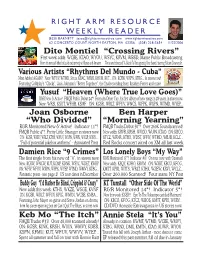

Right Arm Resource 061115.Pmd

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE WEEKLY READER JESSE BARNETT [email protected] www.rightarmresource.com 62 CONCERTO COURT, NORTH EASTON, MA 02356 (508) 238-5654 11/15/2006 Dito Montiel “Crossing Rivers” From his new self-titled cd, exclusvively available through iTunes and Amazon, going for adds now Wrote and directed “A Guide To Recognizing Your Saints” starring Robert Downey Jr. Various Artists “Rhythms Del Mundo - Cuba” Most Added! First week: KCRW, WXPN, KTBG, KSUT, WNRN, KDTR, KWRP... In stores now! Featuring Coldplay’s “Clocks”, Jack Johnson’s “Better Together”, the final recording from Ibrahim Ferrer and more Yusuf “Heaven (Where True Love Goes)” R&R Indicator and FMQB Most Added! From An Other Cup, his first album of new songs in 28 years, in stores now New: WRLT, WYEP, KTHX, KCRW, WCBE... ON: KGSR, WFUV, WNCS, WFPK, WXPN, WTMD, KLRR, KPND... Annie Stela Ben Harper “It’s You” “Morning Yearning” New this week: KWMT! ON: WTMD, WCBE, WMVY, R&R Monitored New & Active! Indicator Most Increased! KTBG, WRNX, DMX, KMTN, KTAO, KUWR, WYOU New: WBCG, KDBB, WAPS, KRVO ON: KBCO, KTCZ, Just finished touring with Joseph Arthur - more dates to come WRNR, KTHX, WDST, WFIV, WTMD, WBJB, KCLC... EP released this past summer, full cd due in January Over 250K scanned! Red Rocks concert airing on XM all this week Buddy Guy “I’d Rather Be Blind, Crippled & Crazy” Los Lonely Boys “My Way” New: KPIG, WMWV, KBAC, KRCC, WFHB, WNTI, KFAN... R&R Monitored 20*! Indicator 5*! Indicator #1 Most Increased! ON: KGSR, WRLT, WFUV, WNRN, WCBE, KNBA, WMVY... New this week: KBCO, WZEW, KRVI ON: WXRT, Featuring John Mayer on guitar and Steve Jordan on drums, KFOG, KMTT, KPRI, WTTS, WRLT, KTHX, WCLZ.. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} up by R.E.M. up by R.E.M

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Up by R.E.M. Up by R.E.M. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 660c7973f8a24e2c • Your IP : 116.202.236.252 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. The Real Reason R.E.M. Broke Up. Regardless of what your opinion about R.E.M. is, there's no denying that they shaped the face of alternative rock for years. Heck, they've basically been every kind of alternative rock band themselves. They spent their formative years as cult favorite college rockers. Then, they started attracting more and more attention until they were making music with genuine mainstream appeal. Between 1991 and 1992 alone, they released the folk- inspired Out of Time and the baroque Automatic For The People, making them easily the most successful band to attack the audiences of the early grunge era with both mandolins ("Losing My Religion") and string arrangements (A good chunk of Automatic ). -

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY FY17 Lieutenant Colonel Army Competitive Category Centralized Selection List

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY FY17 Lieutenant Colonel Army Competitive Category Centralized Selection List - Command and Key Billet PRINCIPALS SLATE Release Date: 21 April 2016 RANK NAME BRANCH HQS SLATED UNIT A02T - COMBAT ARMS (MANEUVER) (02A) - TRAINING LTC ALEXANDER GREGORY KIRK FA TRADOC 1-61 IN (FT JACKSON) LTC BARBOUR JEROME ARTHUR AR TRADOC 3-34 IN REGT (FT JACKSON) LTC BAULT SHAWN M FA TRADOC 2-47 IN (FT BENNING) MAJ/P CHITTY MATTHEW BENJAMIN AR TRADOC 3-11 IN BN (OCS) (FT BENNING) MAJ/P GEORGE MICHAEL J SF TRADOC 3-13 IN BN (FT JACKSON) LTC HALL DANIEL SHANE AR FORSCOM 3-362 IN (FT BLISS) LTC HARRIS ELLIOTT RANDALL FA TRADOC 1-19 FA BN (FT SILL) LTC HEATON RALPH DAVID FA TRADOC 1-40 FA BN (FT SILL) LTC HUBBARD NATHAN MACFARLANE AR TRADOC 2-60 IN BN (FT JACKSON) LTC LENNOX ANDREW JAMES FA FORSCOM 1-314 MAN BN (JBMDL) LTC MACIOCH SIMON ANDREW IN TRADOC 1-31 FA BN (FT SILL) LTC MCGUNEGLE STEVEN BERLE AR TRADOC 2-10 IN BN (FT LEONARD WOOD) MAJ/P MORRIS SHELDON A IN TRADOC 1-46 IN (FT BENNING) LTC PIERI JASON ARTHUR AR TRADOC 2-13 IN BN (FT JACKSON) MAJ/P WHITE MARCUS CHRISTOPHER IN FORSCOM 1-335 MAN BN (CAMP ATTERBURY) A02X - COMBAT ARMS (MANEUVER) (02A) - INSTALLATION LTC DWYER KENNETH M SF IMCOM HUNTER ARMY AIRFIELD (HUNTER AAF) A03P - COMBAT ARMS (MANEUVER) (03A) - OPERATIONS MAJ/P ALBERTUS MATTHEW JOHN IN FORSCOM 4-23 IN (JBLM) MAJ/P ARMSTRONG JAMES EUBANK III AR UNSLATED PRINCIPAL LTC BATTJES MARK EDWARD IN FORSCOM 1-8 IN (FT CARSON) MAJ/P BERRIMAN MICHAEL READ AR FORSCOM 8-1 CAV (CAB) (JBLM) MAJ/P BRAMAN DONALD THOMAS AR FORSCOM 3-61 -

Contemporary

C O N T E M P O R A R Y R E P E R T O I R E f o r S T R I N G Q U A R T E T O N L Y A Hard Day’s Night (The Beatles) Diamonds Are Forever (Shirley Bassey) A Thousand Years (Christina Perri) Disarm (Smashing Pumpkins) Ain't No Mountain High Enough (Marvin Gaye) Don't Stop Believing (Journey) All About That Bass (Meghan Trainor) Don't You Forget About Me (Simple Minds) All Day and All Of The Night (The Kinks) Drive By (Train) All Fall Down (OneRepublic) Edelweiss All of Me (John Legend) Elastic heart (Sia) All My Love (Led Zeppelin) Eleanor Rigby (The Beatles) All You Need is Love (The Beatles) Electric Feel (MGMT) Angel (Sarah McLachlan) Endless Love (Lionel Ritchie) Arrival of the Birds (Cinematic Orchestra) Et Si Tu N'Existais Pas (Joe Dassin) At Last (as performed by Etta James) Every Breath You Take (The Police) Bad Blood (Bastille) Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic (The Police) Bad Romance (Lady Gaga) Every Teardrop is a Waterfall (Coldplay) Beat It (Michael Jackson) Everybody Talks (Neon Trees) Beautiful Day (U2) Fields of Gold (Sting) Begin Again (Taylor Swift) Five Years (David Bowie) Besame Mucho For Your Eyes Only (Sheena Easton) Billie Jean (Michael Jackson) Forget You (CeeLo Green) Billy Joel medley of songs From This Moment On (Shania Twain) (Pressure, Vienna, Uptown Girl, Just The Way You Are, Piano Man) Get Lucky (Daft Punk) Bittersweet Symphony (The Verve) Girls Just Wanna Have Fun (Cyndi Lauper) Black Hole Sun (Soundgarden) Glad You Came (The Wanted) Bleeding Love (Leona Lewis) God Only Knows (Beach Boys) Bohemian Rhapsody -

Crinew Music Re 1Ort

CRINew Music Re 1 ort MARCH 27, 2000 ISSUE 659 VOL. 62 NO.1 WWW.CMJ.COM MUST HEAR Sony, Time Warner Terminate CDnow Deal Sony and Time Warner have canceled their the sale of music downloads. CDnow currently planned acquisition of online music retailer offers a limited number of single song down- CDnow.com only eight months after signing loads ranging in price from .99 cents to $4. the deal. According to the original deal, A source at Time Warner told Reuters that, announced in July 1999, CDnow was to merge "despite the parties' best efforts, the environment 7 with mail-order record club Columbia House, changed and it became too difficult to consum- which is owned by both Sony and Time Warner mate the deal in the time it had been decided." and boasts a membership base of 16 million Representatives of CDnow expressed their customers; CDnow has roughly 2.3 million cus- disappointment with the announcement, and said tomers. With the deal, Columbia House hoped that they would immediately begin seeking other to enter into the e-commerce arena, through strategic opportunities. (Continued on page 10) AIMEE MANN Artists Rally Behind /14 Universal Music, TRNIS Low-Power Radio Prisa To Form 1F-IE MAN \NHO During the month of March, more than 80 artists in 39 cities have been playing shows to raise awareness about the New Latin Label necessity for low power radio, which allows community The Universal Music Group groups and educational organizations access to the FM air- (UMG) and Spain's largest media waves using asignal of 10 or 100 watts. -

WEDNESDAY, JULY 20 Creative Loafing

WEDNESDAY, JULY 20 Creative Loafing National Fortune Cookie Day Doc Chey's Dragon Bowl 1556 N. Decatur Road (Druid Hills/Emory), 11:00 AM Free Celebrate National Fortune Cookie Day at Doc Chey’s Morningside, Grant Park or Dragon Bowl Emory Village. Every guest who dinesin will receive a special fortune cookie with a prize inside, including free food or possibly a Garmin Vivosmart HR Watch. Curiosity Club: Cheeeeeeeeese! Eventide Brewing 1015 Grant St. S.E. (Grant Park), 6:30 PM $30 Every third Wednesday of the month, Eventide Brewing and the Homestead Atlanta’s Curiosity Club series showcases the city’s finest artisans, crafters, and movers through engaging talks and demos. Held at Eventide’s Grant Park brewery, this cheesy event will feature renowned Atlanta cheesemaker Rebecca Williams of Many Fold Farm as she pulls the curtain back on the science and craft of making cheese. Artist Talk: Lauren Weisberger Marcus Jewish Community Center of Atlanta 5342 Tilly Mill Road (Dunwoody), 7:30 PM $10$15 Lauren Weisberger. New York Times bestselling author of The Devil Wears Prada and Revenge Wears Prada comes back to a Page from the Book Festival of the MJCCA to present her new book, The Singles Game. It tells the tale of a tennis prodigy and what she is willing to give up to become the best. There will be a book signing after the discussion, and books will be available for purchase there. Chuck Prophet, Joseph Arthur City Winery 650 North Ave. (Old Fourth Ward), 8:00 PM $22$28 Americana rocker and songwriter for hire (Alejandro Escovedo, Kelly Willis) Chuck Prophet usually tours with his rugged band Mission Express, mopping up clubs with sweatsoaked country rock. -

Right Arm Resource 061122.Pmd

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE WEEKLY READER JESSE BARNETT [email protected] www.rightarmresource.com 62 CONCERTO COURT, NORTH EASTON, MA 02356 (508) 238-5654 11/22/2006 Dito Montiel “Crossing Rivers” First week adds: WCBE, KTAO, WYOU, WSYC, KRVM, WBSD, Maine Public Broadcasting From his new self-titled cd, sold exclusvively at iTunes and Amazon Wrote and directed “A Guide To Recognizing Your Saints” starring Robert Downey Jr. Various Artists “Rhythms Del Mundo - Cuba” Most Added AGAIN! New: WFUV, WTMD, Sirius, KBAC, WBJB, KHUM, KUT... ON: KCRW, WXPN, KTBG... In stores now! Featuring Coldplay’s “Clocks”, Jack Johnson’s “Better Together”, the final recording from Ibrahim Ferrer and more Yusuf “Heaven (Where True Love Goes)” R&R New & Active! FMQB Public Debut 24*! From An Other Cup, his first album of new songs in 28 years, in stores now New: WRSI, KSUT, WFHB, KSMF ON: KGSR, WRLT, WFUV, WNCS, WFPK, WXPN, WTMD, WYEP... Joan Osborne Ben Harper “Who Divided” “Morning Yearning” R&R Monitored New & Active! Indicator 11*! FMQB Tracks Debut 50*! Over 260K Soundscanned! FMQB Public 4*! Pretty Little Stranger in stores now New adds: KRVB, KRSH, WVOD, WUIN, KTAO ON: KBCO, O N: KGSR, WXRV, WRLT, KTHX, WFUV, WXPN, WFPK, WYEP, WXPK... KTCZ, WRNR, KTHX, WDST, WFIV, WTMD, WBJB, KCLC... “Full of potential jukebox anthems” - Associated Press Red Rocks concert aired on XM all last week Damien Rice “9 Crimes” Los Lonely Boys “My Way” The first single from his new cd “9”, in stores now R&R Monitored 15*! Indicator #6! On tour now with Ozomatli New: KCRW, WNCW, KUT, KCMP, KDNK, WSYC, WDET, KWRP New adds: KSQY, KOHO, KBOM ON: WXRT, KBCO, KFOG, ON: WFIV, WFUV, WXPN, WFPK, WYEP, WTMD, WMVY, KTBG.. -

College of Life Sciences Convocation Brigham Young University April 24, 2015 11:00 A.M. Marriott Center

ONE HUNDRED AND FORTIETH College of Life Sciences Convocation Brigham Young University April 24, 2015 11:00 a.m. Marriott Center Program Administrative Representative Craig H. Hart Associate Academic Vice President Welcome Dean Rodney J. Brown Invocation Morgan Christiansen Student Address Brady Hunt Vocal Duet Ariana and Eric Fonnesbeck “O Divine Redeemer” Ben Walley, accompanist Words and music by Charles Gounod Student Address Zachary Liechty Presentation of Diplomas Deans and Department Chairs Remarks Dean Rodney J. Brown Benediction Cerissa Hayhurst Prelude and Recessional Music Sheri Peterson The audience will please remain seated until the recessional is complete. Convocation Participants The following are honored students chosen by their departments as exemplary student representatives. The speakers and prayers have been selected from among these students. Morgan Christiansen is the daughter of Stephen and Christy Christiansen of Bountiful, Utah, and is married to Eric Nelson. She is graduating magna cum laude in molecular biology. Morgan received a full-tuition scholarship throughout college and was on the dean’s list six consecutive semesters. She earned a 2014–15 Myriad Excellence Scholarship and the 2014 Garth L. Lee Undergraduate Teaching Award. Morgan served as Life Sciences Student Council vice president from 2014 to 2015 and was in the HART Club presidency from 2013 to 2014. She also was a teaching assistant for organic chemistry for four semesters and a research assistant in an immunology lab. Morgan enjoys running, playing soccer and racquetball, and spending time with her husband and family. After graduation she will be pursuing a graduate degree in molecular biology. Cerissa Hayhurst is the daughter of Ren and Rena Hayhurst of Aliso Viejo, California. -

Piano Instrumental List

Antoine Robinson (www.weddingpianist.co) | PIANO INSTRUMENTAL LIST P a g e | 1 LOVE SONGS/BALLADS/SLOW Power of love (Jennifer Rush) SHOWS/MUSICALS INSTRUMENTAL/’CLASSICAL’ Ain’t no sunshine (Bill Withers) Promise me (Beverley Craven) All I ask of you (Phantom) Canon in D (Johann Pachelbel) Always (Bon Jovi) Raining in my heart (Buddy Holly) Any dream will do (Andrew Lloyd Webber) Fur Elise (Beethoven) Always on my mind (Elvis Presley) Rainy days and Mondays (The Carpenters) A whole new world (Aladdin) Glasgow Love Theme (Craig Armstrong) Amazed (Lonestar) Someone like you (Adele) Can you feel the love tonight? (Lion King) Nessun dorma (Pavarotti) Angels (Robbie Williams) Something in the way (the Beatles) Don’t cry for me Argentina (Lloyd Webber) River flows in you (Yiruma) Annie’s song (John Denver) Somewhere over the rainbow How far I’ll go (Moana) Watermark (Enya) Another day in paradise (Phil Collins) Tears in Heaven (Eric Clapton) I dreamed a dream (Schönberg/Boublil) Ave Maria (Beyonce version) Titanic theme (Celine Dion) I know him so well (E. Paige/B. Dickson) BLUES/FOLK Back for good (Take that) Thank you for the music (Abba) Let it go (Frozen) Blowin' in the wind (Bob Dylan) Ben (Michael Jackson) The Winner takes it all (Abba) Memories (Andrew Lloyd Webber) Bridge over troubled water (Simon/Garfunkel) Bitter sweet symphony (The Verve) True colours (Cyndi Lauper) Million dreams (Greatest Showman) Streets of London (Ralph McTell) Can you feel the love tonight? (Elton John) Unchained melody (Righteous brothers) Music of the night (A Lloyd Webber/T. Rice) Candle in the wind (Elton John) When I fall in love (Nat King Cole) Never enough (Greatest Showman) POP/ROCK/LIVELY Careless whisper (George Michael) When I need you (Leo Sayer) Rewrite the stars (Greatest Showman) Bohemium Rhapsody (Queen) Closest thing to crazy (Katie Mellua) While my guitar gently weeps (G. -

(税抜) URL 27 Let the Light In

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 27 Let The Light In PTCD1005 CD ROCK/POP 1,050 https://tower.jp/item/1108715 27 ブリトル ディヴィニティ(+BT) SKMN9 CD ROCK/POP 1610 https://tower.jp/item/2897184 44 When Your Heart Stops Beating B000775402 CD ROCK/POP 945 https://tower.jp/item/2131775 1981 Antems For Doomed Youth VOX4 CD ROCK/POP 972.3 https://tower.jp/item/3558774 1984 Rage with No Name DRR023 CD ROCK/POP 1,445 https://tower.jp/item/4619808 !!! アズ イフ(+1) BRC481 CD ROCK/POP 1,478 https://tower.jp/item/3968983 !!! Shake The Shudder <初回限定生産盤> [CD+Tシャツ(Mサイズ)] BRC545TM CD ROCK/POP 3,850 https://tower.jp/item/4478130 !!! Wallop(金曜販売開始商品/LP) WARPLP302 Analog ROCK/POP 2023 https://tower.jp/item/4926114 (((Vluba))) Exile to Another Dimension MA16 CD ROCK/POP 1,050 https://tower.jp/item/4495959 ******** [The Drink] The Drink [********](UK) WEIRD105CD CD ROCK/POP 1673 https://tower.jp/item/4662908 ...And You Will Know Us By The Trザ センチュリー オブ セルフ PCD93218 CD ROCK/POP 1610 https://tower.jp/item/2519319 //Tense// メモリー CLTCD2011 CD ROCK/POP 1610 https://tower.jp/item/3060236 @ L'URLO INTERISTA (JP) GAR2 CD ROCK/POP 1,500 https://tower.jp/item/809822 @ GRAZIE ROMA (JP) GAR3 CD ROCK/POP 1,500 https://tower.jp/item/809823 @ IL MEGLIO DI MUSICA & GOAL VOL (JP) GRO15 CD ROCK/POP 1,500 https://tower.jp/item/809832 @ GRANDE FIORENTINA (JP) GRO12 CD ROCK/POP 1,500 https://tower.jp/item/809829 @ GENOA NEL CUORE(JP) GAR13 CD ROCK/POP 1,750 https://tower.jp/item/809830 @ URRA' SAMPDORIA! (JP) GRO14 CD ROCK/POP 1,500 https://tower.jp/item/809831 @ ナイトクラブ スプラッシュ NACL1159 -

At a Glance Concert Schedule

At A Glance Concert Schedule SC- Supper Club CH- Concert Hall MB- Music Box Full Venue RT- Rooftop Deck RF- Riverfront Porch PDR- Private Dining Room Sun 5/21 CH Turning Point Church Presented by NEO Church Planting network Weekly Worship Service (View Page) Sun 5/21 SC Beatles Brunch With The Sunrise Jones (Tickets) Wed 5/24 SC Topic: Cleveland Car Show Storyteller: Dr. Ed Pershey Cleveland Stories Dinner Parties (View Page) Wed 5/24 CH Dreadlock Dave & Friends Documentary Filming Live Concert! (Tickets) Thu 5/25 SC Steely Dan Tribute by The FM Project Northeast Ohio's Premier Steely Dan Tribute (View Page) Thu 5/25 CH The Secret Sisters Old Fashioned Alabama Roots Melodies (Tickets) Fri 5/26 CH The Classic Rock-Off! & Rooftop Picnic It's the Stones vs Beatles vs Petty vs Allman Brothers, by The Sunrise Jones (View Page) Fri 5/26 SC Motown Night with Nitebridge & The NB Horns Enjoy the jumpin' sounds of your favorite classic hits! (View Page) Fri 5/26 SC Late Nite Lounge: Drag Bingo Free Admission and Free Bingo! Win fun bar swag and prizes from Ambiance, a store for lovers! (View Page) Sat 5/27 SC Travis Haddix Blues Band Award-winning blues guitarist known as "The Moonchild" (View Page) Sun 5/28 CH Turning Point Church Presented by NEO Church Planting network Weekly Worship Service (View Page) Sun 5/28 SC Janis Joplin Brunch With Ball & Chain (View Page) Sun 5/28 SC Blues DeVille Jumpin' Rockin' Blues (View Page) Wed 5/31 SC Topic: The Election of Carl Stokes – 50 Years Ago Cleveland Made History! Storyteller: Susan L.