Production of Vitamin B-12 in Tempeh, a Fermented Soybean Food

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE October 27, 2019 RESOBOX East Village 91 E 3rd St, New York, NY 10003 DISCOVER THE VERSATILITY of TOFU ~Japanese Vegan Cooking Event~ Date: Sunday, November 3, 2019 10:00am - 12:00pm Where: RESOBOX East Village 91 E 3rd St, New York, NY 10003 Price: $60 (includes all materials) Contact: Takashi Ikezawa, 718-784-3680, [email protected] Web: https://resobox.com/event/discover-the-versatility-of-tofu-japanese-veGan-cookinG-event/ “Try and Experience the Various Textures of Tofu” “Discover Recipes for Tofu Cuisines” “Taste The Many Textures of Tofu” Event Overview Tofu has one of the few plant-based proteins that contain all of the essential amino acids we need to stay healthy. Tofu – a protein-rich, healthy superfood – is not all the same. It has several types of textures, tastes, and appearances depending on the country of oriGin. For this workshop, participants will cook using three types of Japanese tofu! They will learn the basics of tofu including the differences between soft, medium, and firm Tofu and how to cook each texture. See below for a full below outline of what’s in store: 1. Understanding the characteristics of soft, medium, and firm tofu such as production method, how to choose the riGht tofu, recipes, and more. Expand your knowledGe on Tofu! Participants will learn the characteristic of each texture and how to prepare them while tasting different types of Tofu. 2. Cooking using soft, medium, and firm tofu: 1. Tofu Teriyaki Steak Sandwich • Firm Tofu • Soy Sauce • Brown Sugar • Sweet Sake • Refined Sake • Ginger • Potato Starch • Seasonal VeGetables • Bread 2. -

Read Book Wagashi and More: a Collection of Simple Japanese

WAGASHI AND MORE: A COLLECTION OF SIMPLE JAPANESE DESSERT RECIPES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Cooking Penguin | 72 pages | 07 Feb 2013 | Createspace | 9781482376364 | English | United States Wagashi and More: A Collection of Simple Japanese Dessert Recipes PDF Book Similar to mochi, it is made with glutinous rice flour or pounded glutinous rice. Tourists like to buy akafuku as a souvenir, but it should be enjoyed quickly, as it expires after only two days. I'm keeping this one a little under wraps for now but if you happen to come along on one of my tours it might be on the itinerary Next to the velvety base, it can also incorporate various additional ingredients such as sliced chestnuts or figs. For those of you who came on the inaugural Zenbu Ryori tour - shhhhhhhh! Well this was a first. This classic mochi variety combines chewy rice cakes made from glutinous rice and kinako —roasted soybean powder. More about Hishi mochi. The sweet and salty goma dango is often consumed in August as a summer delicacy at street fairs or in restaurants. The base of each mitsumame are see-through jelly cubes made with agar-agar, a thickening agent created out of seaweed. Usually the outside pancake-ish layer is plain with a traditional filling of sweet red beans. Forgot your password? The name of this treat consists of two words: bota , which is derived from botan , meaning tree peony , and mochi , meaning sticky, pounded rice. Dessert Kamome no tamago. Rakugan are traditional Japanese sweets prepared in many different colors and shapes reflecting seasonal, holiday, or regional themes. -

Pouring Plates from Prepared Bottled Media

Pouring Plates from Prepared Bottled Media Primary Hazard Warning Never purchase living specimens without having a disposition strategy in place. When pouring bottles, agar is HOT! Burning can occur. Always handle hot agar bottles with heat-protective gloves. For added protection wear latex or nitrile gloves when working with bacteria, and always wash hands before and after with hot water and soap. Availability Agar is available for purchase year round. Information • Storage: Bottled agar can be stored at room temperature for about six months unless otherwise specified. Never put agar in the freezer. It will cause the agar to breakdown and become unusable. To prevent contamination keep all bottles and Petri dishes sealed until ready to use. • Pouring Plates • Materials Needed: • Draft-free enclosure or Laminar flow hood • 70% isopropyl alcohol • Petri dishes • Microwave or hot water bath or autoclave 1. Melt the agar using one of the following methods: a) Autoclave: Loosen the cap on the agar bottle and autoclave the bottle at 15 psi for five minutes. While wearing heat-protective gloves, carefully remove the hot bottle and let it cool to between 75–55°C before pouring. This takes approximately 15 minutes. b)Water Bath: Loosen the cap on the agar bottle and place it into a water bath. Water temperature should remain at around 100°C. Leave it in the water bath until the agar is completely melted. While wearing heat- protective gloves, carefully remove the hot bottle and let it cool to between 75–55°C before pouring. c) Microwave: Loosen the cap on the agar bottle before microwaving. -

KERUPUK SINGKONG EBI’ – Inovasi Jenis Kerupuk Dengan Singkong Dan Ebi

USULAN PROGRAM KREATIVITAS MAHASISWA JUDUL PROGRAM KRISBI ’KERUPUK SINGKONG EBI’ – Inovasi Jenis Kerupuk dengan Singkong dan Ebi BIDANG KEGIATAN: PKM-KEWIRAUSAHAAN Diusulkan oleh: Prio Pramujio NIM : A12.2012.04589 Andoko NIM : D22.2011.011166 Arya Santosa NIM : B11.2012.02555 UNIVERSITAS DIAN NUSWANTORO SEMARANG 2013 PENGESAHAN USULAN PKM-KEWIRAUSAHAAN 1. Judul Kegiatan : KRISBI ’KERUPUK SINGKONG EBI’ – Inovasi Jenis Kerupuk dengan Singkong dan Ebi 2. Bidang Kegiatan : PKM-K 3. Ketua Pelaksana Kegiatan a. Nama Lengkap : Prio Pramujio b. NIM : A12.2012.04589 c. Jurusan : S1 Sistem Informasi d. Universitas : Universitas Dian Nuswantoro e. Alamat Rumah dan No Tel./HP : Ds. Sikayu Kec. Comal Kab. Pemalang 087711581196 f. Alamat e-mail : [email protected] 4. Anggota Pelaksana Kegiatan : 3 Orang 5. Dosen Pendamping a. Nama Lengkap dan Gelar : Fahri Firdausillah, S.Kom, MCS b. NIDN : 0605078601 c. Alamat Rumah dan No Telp/HP : Jl.Dewi Sartika Timur X No.22 RT 07 RW 05 Kelurahan Sukorejo Gunung Pati Semarang / 0243547038 6. Biaya Kegiatan Total a. Dikti : Rp 11.428.500,00 b. Sumber Lain : - 7. Jangka Waktu Pelaksanaan : 4 bulan Semarang, 05 Oktober 2013 Menyetujui, Ketua Program Studi Ketua Pelaksana Sri Winarno, M.Kom Prio Pramujio NIP. 0686.11.1998.142 NIM. A12.2012.04589 Wakil Rektor Bidang Kemahasiswaan Dosen Pendamping Usman Sudibyo, S.Si, M.Kom Fahri Firdausillah, S.Kom, MCS NIP. 0686.11.1996.101 NIDN. 0605078601 ii DAFTAR ISI PENGESAHAN USULAN PKM-KEWIRAUSAHAAN .............................................................. ii DAFTAR -

Tofu Fa with Sweet Peanut Soup

Tofu Fa with Sweet Peanut Soup This a recipe for the traditional Taiwanese dessert made with soy milk. Actually it is a soy custard served with sweet peanut soup. It is a lighter version of tofu in terms of texture. This recipe might sound strange for you if you were never been exposed to it. If you are familiar with dim sum, you might have encountered this dessert, but if you have never tried I encourage you to give this a try. Tofu Fa or toufa…it is a traditional Chinese snack based on soy, like tofu, but much tender and silkier. In Taiwan it is served with cooked peanut soup (sweet), red bean, oatmeal, green beans or a combination of these items, depending of your taste. Here I have it with a sweet peanut soup…yes, it sounds strange right? Yes, but once you try, might my get addicted to it…like my husband… I kind of use the short cut, I used the tofu-fa from a box (comes with a package of dry soy powder and gypsum) but if you want you can make your own soy milk and add gypsum, which is a tofu coagulant. Gypsum is used in some brewers and winemakers to adjust the pH. Some recipes call for gelatin or agar-agar…but these are different from tofu, they are more jelly like, and the texture and consistency are different from tofu. Going back to tofu-fa, I followed the instructions from the box, please make sure that you add the appropriate amount of water for tofu-fa, otherwise you will end up with regular tofu and not the custard like texture. -

When Taking Medication May Be a Sin: Dietary Requirements and Food Laws

BJPsych Advances (2015), vol. 21, 425–432 doi: 10.1192/apt.bp.114.012534 When taking medication may be a ARTICLE sin: dietary requirements and food laws in psychotropic prescribing Waqqas A. Khokhar, Simon L. Dein, Mohammed S. Qureshi, Imran Hameed, Mohammed M. Ali, Yasir Abbasi, Hasan Aman & Ruchit Sood In psychiatric practice, it is not uncommon to Waqqas A. Khokhar is a SUMMARY come across patients who refuse any psychiatric consultant psychiatrist with Leicestershire Partnership NHS Religious laws do not usually forbid the use of intervention, placing their faith in a spiritual psychotropic medication, but many do forbid the Trust and an honorary lecturer in recovery enabled by their religious beliefs (Campion the Centre for Ageing and Mental consumption of animal-based derivatives of bovine 1997; Koenig 2001). Although religious laws do Health at Staffordshire University. and/or porcine origin (e.g. gelatin and stearic not usually restrict the taking of psychotropic Simon L. Dein is a senior lecturer acid) such as are found in many medications. at University College London, an Demonstrating awareness of this, combined with medication, many do forbid consumption of the Honorary Clinical Professor at a genuine concern about how it affects the patient, animal derivatives, particularly gelatin and stearic the University of Durham and a may strengthen the doctor–patient relationship acid, that many psychotropics contain. This has consultant psychiatrist with the and avoid non-adherence. In this article, we major implications, for example, for patients who North Essex Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust. Mohammed outline dietary requirements of key religions and follow Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism and S. -

The Hip Chick's Guide to Macrobiotics Audiobook Bonus: Recipes

1 The Hip Chick’s Guide to Macrobiotics Audiobook Bonus: Recipes and Other Delights Contents copyright 2009 Jessica Porter 2 DO A GOOD KITCHEN SET-UP There are some essentials you need in the kitchen in order to have macrobiotic cooking be easy and delicious. The essentials: • A sharp knife – eventually a heavy Japanese vegetable knife is best • Heavy pot with a heavy lid, enameled cast iron is best • Flame deflector or flame tamer, available at any cooking store • A stainless steel skillet • Wooden cutting board • Cast iron skillet Things you probably already have in your kitchen: • Blender • Strainer • Colander • Baking sheet • Slotted spoons • Wooden spoons • Mixing bowls • Steamer basket or bamboo steamer 3 You might as well chuck: • The microwave oven • Teflon and aluminum cookware Down the road: • Stainless-steel pressure cooker • Gas stove • Wooden rice paddles You know you’re really a macro when you own: • Sushi mats • Chopsticks • Suribachi with surikogi • Hand food mill • Juicer • Ohsawa pot • Nabe pot • Pickle press • A picture of George Ohsawa hanging in your kitchen! Stock your cupboard with: • A variety of grains • A variety of beans, dried • Canned organic beans • Dried sea vegetables • Whole wheat bread and pastry flour • A variety of noodles • Olive, corn, and sesame oil • Safflower oil for deep frying 4 • Shoyu, miso, sea salt • Umeboshi vinegar, brown rice vinegar • Mirin • Sweeteners: rice syrup, barley malt, maple syrup • Fresh tofu and dried tofu • Boxed silken tofu for sauces and creams • A variety of snacks from the health-food store • Tempeh • Whole wheat or spelt tortillas • Puffed rice • Crispy rice for Crispy Rice Treats • Organic apple juice • Amasake • Bottled carrot juice, but also carrots and a juicer • Agar agar • Kuzu • Frozen fruit for kanten in winter • Dried fruit • Roasted seeds and nuts • Raw vegetables to snack on • Homemade and good quality store- bought dips made of tofu, beans, etc. -

Cafe Menu Sauteed Veggies* on Organic Non-GMO Corn ORGANIC WHEAT GRASS, Oz

Welcome... V VEGAN: as is Chicken & Fish Pasta Smoothies Shakes V GF All Smoothies VO VEGAN OPTION: can be made vegan Add a small side salad to any entree GF ...2.95 GF All Shakes Our Menu offers options for MOONLIGHT PASTA ..........................9.95 Frozen blended drinks made with fruit HV HONEY-VEGAN: vegan with honey CHICKEN-STUFFED SPUD ................9.95 Pasta of the day tossed with fresh homemade Topped with whipped cream. many dietary preferences. and fruit juice only. ............................... 3.95 Baked potato stuffed with chicken in ran- marinara and Parmesan cheese or pesto* and Use these Icons to find HVO HONEY-VEGAN OPTION: can be honey-vegan ADD protein powder ..............................95 VO Soy Shakes upon request. ADD ...........95 chero sauce topped with sour cream and feta cheese, served with a salad garnish and No ice, sherbet or fillers. items that fit your needs. GF GLUTEN FREE: No wheat, rye, barley or oat gluten guacamole. With salad garnish. GF garlic bread. *Contains nuts VANILLA .............................................3.95 Vanilla extract, vanilla ice cream, milk. GFO GLUTEN FREE OPTION: Can be made GF STRAWBERRY BANANA BOOST CHICKEN ENCHILADAS ...................9.95 Note: Sub GF bread, add 25¢ per slice SWAMI’S LASAGNA ..........................9.95 Strawberry, Banana, Organic Apple juice CHOCOLATE ......................................3.95 Organic Non-GMO corn tortillas stuffed Veggie lasagna made of spinach pasta, ricotta PEACH-ANANDA Chocolate syrup, vanilla ice cream, milk. with ranchero chicken, black beans, organic cheese, fresh vegetables and marinara sauce Peach, Banana, Peach juice rice, and cheese topped with ranchero with garlic bread. STRAWBERRY .....................................3.95 sauce, sour cream and guacamole. -

Recipe Books in North America

Greetings How have Japanese foods changed between generations of Nikkei since they first arrived in their adopted countries from Japan? On behalf of the Kikkoman Institute for International Food Culture (KIIFC), Mr. Shigeru Kojima of the Advanced Research Center for Human Sciences, Waseda University, set out to answer this question. From 2015 to 2018, Mr. Kojima investigated recipe books and conducted interviews in areas populated by Japanese immigrants, particularly in Brazil and North American, including Hawaii. His research results on Brazil were published in 2017 in Food Culture No. 27. In this continuation of the series, he focuses on North America. With the long history of Japanese immigration to North America, as well as Nikkei internments during WWII, the researcher had some concerns as to how many recipe books could be collected. Thanks to Mr. Kojima’s two intensive research trips, the results were better than expected. At a time of increasing digitization in publishing, we believe this research is both timely and a great aid in preserving historical materials. We expect these accumulated historical materials will be utilized for other research in the future. The KIIFC will continue to promote activities that help the public gain a deeper understanding of diverse cultures through the exploration of food culture. CONTENTS Feature Recipe Books in North America 3 Introduction Recipe Books Published by Buddhist Associations and Other Religious Groups 10 Recipe Books Published by Nikkei Associations (Excluding Religious Associations) 13 Mobile Kitchen Recipe Books 15 Recipe Books Published by Public Markets and Others 17 Books of Japanese Recipes as Ethnic Cuisine 20 Recipe Books as Handbooks for Living in Different Cultures 21 Hand-written Recipe Books 22 Summary Shigeru Kojima A research fellow at the Advanced Research Center for Human Sciences, Waseda University, Shigeru Kojima was born in Sanjo City, Niigata Prefecture. -

Tipu's Tiger - CLOSED 115 1/2 Missoula, Montana Phone: (406) 555-5555

Tipu's Tiger - CLOSED 115 1/2 Missoula, Montana phone: (406) 555-5555 hours: Menu created with The Grub Club® Appetizers The following appetizers served with date-raisin and raita Chutney, except where noted. Samosas(triangular fried pastries with different fillings, two per order) :: * Vegetable Samosa - a mixture of potatoes, cabbage, corn, peas and onions spiced to create a Tipu's favorite! ____ $4 :: Spinach and Paneer Samosa - fresh spinach and paneer (our homemade cheese) mixed with delicately spiced potatoes ____ $5 :: Mushroom-Walnut Samosa - finely chopped button mushrooms and crushed walnuts spiced with fenugreek, ginger and garlic ____ $5 :: Mixed Samosa Plate - a sampling of each ____ $6 Other Tipu's Favorites :: * Potato and Onion Bhajis - grated potatoes and sliced Onion mixed into a garbanzo batter and fried ____ $5 :: Stuffed Chapati - two pieces of our homemade flatbread filled with a spicy-sweet mango chutney and cheese then grilled ____ $6 :: Child's Stuffed Chapati - made without the spicy-sweet mango chutney ____ $5 :: * Spicy Yam fries - wedges of fresh yams fried, spiced and served with Tamarind-chili chutney ____ $4 :: * Papadams - two spicy crispy lentil wafers, served with tamatar chutney ____ $3 * denotes Vegan items, don't hesitate to ask your server if you have any questions. Soup, Salad and Breads Soups :: Daily Soup Special - varies daily ____ $5 bowl or $3 cup :: * Tharka Dahl - organic red lentils cooked with garlic, cumin and a touch of jalapeno puree ____ $5 bowl or $3 cup Ask your server what our -

Temptations Buffet Dinner Menu Cycle

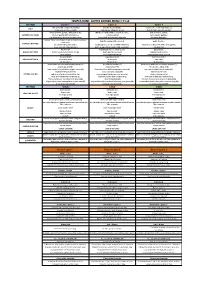

TEMPTATIONS BUFFET DINNER MENU CYCLE SECTION Cycle 1 Cycle 2 Cycle 3 soto ayam with condiments (malay) Tomato rassam (indian) chicken sweet corn soup (chinese) SOUP cream of peas cheese twisty Crab bisque with garlic bread french onion soup and crouton Roasted root vegetables with garlic herbs Mini beef schnitzel with creamy herb sauce stuffed chicken roulade WESTERN HOT FOOD chicken picatta with tomato puree seabass papillot roasted garlic potatoes irish lamb shank stew with mashed potato baked herb tossed butter vegetable hungarian beef stew Braised Chinese mushroom, fungi mushroom & garden Wok-fried prawn with curry leaf garlic fried rice vegetables CHINESE HOT FOOD Special fried imperial noodles Crispy Japanese bean curd with mushrooms Crispy fried seabass with butter and egg floss sweet and sour crispy garoupa Black pepper Udon noodles with vegetables Loh hon chai Nasi tomato Kambing kicap berempah pedas pajeri nanas MALAY HOT FOOD Ketam masak masam Manis (Crab) Ayam goreng berempah Daging masak kerutub sayur campur sayur lodeh with tempeh udang masak lemak cili padi dal panchratni vegetable biryani Dal lasooni tadka INDIAN HOT FOOD aloo simla mirch chana pindi corn palak Steamed rice Steamed rice Steamed rice pasta sation with mac and cheese poppers (T) Elivated pasta sation (T) pasta sation with mac and cheese poppers (T) popiah basah (CB) yong tau foo (CB) Chicken rice station (CB) herb crusted beef with black pepper sauce(W) Roasted chicken with black pepper sauce(W) salt crusted whole baked seabass(W) vegetable tempura live -

MW Efficacy In

Journal of International Dental and Medical Research ISSN 1309-100X Database of carboxymethyl lysine in foods http://www.jidmr.com Patricia Budihartanti Liman and et al Database Development of Carboxymethyl Lysine Content in Foods Consumed by Indonesian Women in Two Selected Provinces Patricia Budihartanti Liman1,2,3, Ratna Djuwita4, Rina Agustina1,3,5* 1. Department of Nutrition, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia. 2. Department of Nutrition, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Trisakti, Jakarta, Indonesia. 3. Human Nutrition Research Centre, Indonesian Medical Education and Research Institute (IMERI), Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia. 4. Department of Epidemiology, Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia 5. Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization Regional Center for Food and Nutrition (SEAMEO RECFON) – Pusat Kajian Gizi Regional Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia Abstract Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in foods are increased by heat processing, and high consumption of these compounds could contribute to the pathogenesis of non-communicable disease. Yet, the information on carboxymethyl lysine (CML) content, as a part of AGEs, in dietary intakes with predominantly traditional foods with diverse food processing is lacking. We developed a database of Indonesian foods to facilitate studies involving the assessment of dietary and plasma CML concentration by liquid-chromatography-tandem-mass spectrometry. We estimated dietary CML values of 206 food items from 2-repeated 24-h recalls of 235 Indonesian women with the mean age of 36±8 years old in a cross-sectional study. All foods were listed and grouped according to the Indonesian food composition table, completed for cooking methods, amount of consumptions, and ingredients.