Molecular Detection of Human Parasitic Pathogens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRBA 464 Biologische Arbeitsstoffe in Risikogruppen

Ausgabe Juli 2013 Technische Regeln für Einstufung von Parasiten TRBA 464 Biologische Arbeitsstoffe in Risikogruppen Die Technischen Regeln für Biologische Arbeitsstoffe (TRBA) geben den Stand der Technik, Arbeitsmedizin und Arbeitshygiene sowie sonstige gesicherte wissenschaftliche Erkenntnisse für Tätigkeiten mit biologischen Arbeitsstoffen, einschließlich deren Einstufung, wieder. Sie werden vom Ausschuss für Biologische Arbeitsstoffe ermittelt bzw. angepasst und vom Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales im Gemeinsamen Ministerialblatt bekannt gegeben. Die TRBA „Einstufung von Parasiten in Risikogruppen“ konkretisiert im Rahmen des Anwendungsbereichs die Anforderungen der Biostoffverordnung. Bei Einhaltung der Technischen Regeln kann der Arbeitgeber insoweit davon ausgehen, dass die entsprechenden Anforderungen der Verordnung erfüllt sind. Die Einstufungen der biologischen Arbeitsstoffe in Risikogruppen werden nach dem Stand der Wissenschaft vorgenommen; der Arbeitgeber hat die Einstufung zu beachten. Die vorliegende Technische Regel schreibt die Technische Regel „Einstufung von Parasiten in Risikogruppen“ (Stand Oktober 2002) fort und wurde unter Federführung des Fachbereichs „Rohstoffe und chemische Industrie“ in Anwendung des Kooperationsmodells (vgl. Leitlinienpapier1 zur Neuordnung des Vorschriften- und Regelwerks im Arbeitsschutz vom 31. August 2011) erarbeitet. Inhalt 1 Anwendungsbereich 2 Allgemeines 3 Liste der Einstufungen der Parasiten 3.1 Vorbemerkungen 3.2 Einstufung der Endoparasiten von Mensch und Haustieren (einschließlich -

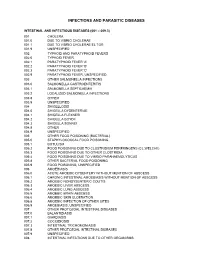

Diagnostic Code Descriptions (ICD9)

INFECTIONS AND PARASITIC DISEASES INTESTINAL AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES (001 – 009.3) 001 CHOLERA 001.0 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE 001.1 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE EL TOR 001.9 UNSPECIFIED 002 TYPHOID AND PARATYPHOID FEVERS 002.0 TYPHOID FEVER 002.1 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'A' 002.2 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'B' 002.3 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'C' 002.9 PARATYPHOID FEVER, UNSPECIFIED 003 OTHER SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.0 SALMONELLA GASTROENTERITIS 003.1 SALMONELLA SEPTICAEMIA 003.2 LOCALIZED SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.8 OTHER 003.9 UNSPECIFIED 004 SHIGELLOSIS 004.0 SHIGELLA DYSENTERIAE 004.1 SHIGELLA FLEXNERI 004.2 SHIGELLA BOYDII 004.3 SHIGELLA SONNEI 004.8 OTHER 004.9 UNSPECIFIED 005 OTHER FOOD POISONING (BACTERIAL) 005.0 STAPHYLOCOCCAL FOOD POISONING 005.1 BOTULISM 005.2 FOOD POISONING DUE TO CLOSTRIDIUM PERFRINGENS (CL.WELCHII) 005.3 FOOD POISONING DUE TO OTHER CLOSTRIDIA 005.4 FOOD POISONING DUE TO VIBRIO PARAHAEMOLYTICUS 005.8 OTHER BACTERIAL FOOD POISONING 005.9 FOOD POISONING, UNSPECIFIED 006 AMOEBIASIS 006.0 ACUTE AMOEBIC DYSENTERY WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.1 CHRONIC INTESTINAL AMOEBIASIS WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.2 AMOEBIC NONDYSENTERIC COLITIS 006.3 AMOEBIC LIVER ABSCESS 006.4 AMOEBIC LUNG ABSCESS 006.5 AMOEBIC BRAIN ABSCESS 006.6 AMOEBIC SKIN ULCERATION 006.8 AMOEBIC INFECTION OF OTHER SITES 006.9 AMOEBIASIS, UNSPECIFIED 007 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.0 BALANTIDIASIS 007.1 GIARDIASIS 007.2 COCCIDIOSIS 007.3 INTESTINAL TRICHOMONIASIS 007.8 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.9 UNSPECIFIED 008 INTESTINAL INFECTIONS DUE TO OTHER ORGANISMS -

Aremu SO, Et Al. Putting the Spotlight on Opisthorchiasis: the Dread of the Western Siberian Copyright© Aremu SO, Et Al

Public Health Open Access MEDWIN PUBLISHERS ISSN: 2578-5001 Committed to Create Value for researchers Putting the Spotlight on Opisthorchiasis: The Dread of the Western Siberian Region Aremu SO1,3*, Zephaniah HS2, Onifade EO3, Fatoke B1 and Bademosi O4 Review Article 1Faculty of General Medicine, Siberian State Medical University, Tomsk, Russian Federation Volume 4 Issue 1 2Department of Biochemistry, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria Received Date: February 17, 2020 3Department of Biological Science, Federal University of Agriculture, Makurdi Benue State, Published Date: March 10, 2020 Nigeria DOI: 10.23880/phoa-16000151 4Department of Public Health, University College Dublin, Ireland *Corresponding author: Stephen Olaide Aremu, Faculty of General Medicine, Siberian State Medical University, Tomsk, Russian Federation, Email: [email protected] Abstract Introduction: Opisthorchiasis is no doubt one of the most neglected infectious disease inspite of its huge medical importance in some parts of the World. The past decade have seen a resurgence of interests in research relating to this public health issue, however there is still a lot to be done. Social Model: Not many models have been explored in Western Siberia to deal with the opisthorchiasis epidemic when compared to the different models that have been used for other regions affected by similar disease. Life Cycle: The complex life cycle of Opisthorchis felineus prevalent among the aboriginal population of the Western Siberian because of their habit of eating raw or undercooked fresh has humans and other feline species as definitive host and is really Diagnosis and Treatment: Diagnosis involve the use of stool microscopy, other methods such as mAb ELISA, LAMP and so on water fish (Cyprinidae) which are intermediate host of the parasite. -

Acanthamoeba Spp., Balamuthia Mandrillaris, Naegleria Fowleri, And

MINIREVIEW Pathogenic and opportunistic free-living amoebae: Acanthamoeba spp., Balamuthia mandrillaris , Naegleria fowleri , and Sappinia diploidea Govinda S. Visvesvara1, Hercules Moura2 & Frederick L. Schuster3 1Division of Parasitic Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases, Atlanta, Georgia, USA; 2Division of Laboratory Sciences, National Center for Environmental Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA; and 3Viral and Rickettsial Diseases Laboratory, California Department of Health Services, Richmond, California, USA Correspondence: Govinda S. Visvesvara, Abstract Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Chamblee Campus, F-36, 4770 Buford Among the many genera of free-living amoebae that exist in nature, members of Highway NE, Atlanta, Georgia 30341-3724, only four genera have an association with human disease: Acanthamoeba spp., USA. Tel.: 1770 488 4417; fax: 1770 488 Balamuthia mandrillaris, Naegleria fowleri and Sappinia diploidea. Acanthamoeba 4253; e-mail: [email protected] spp. and B. mandrillaris are opportunistic pathogens causing infections of the central nervous system, lungs, sinuses and skin, mostly in immunocompromised Received 8 November 2006; revised 5 February humans. Balamuthia is also associated with disease in immunocompetent chil- 2007; accepted 12 February 2007. dren, and Acanthamoeba spp. cause a sight-threatening infection, Acanthamoeba First published online 11 April 2007. keratitis, mostly in contact-lens wearers. Of more than 30 species of Naegleria, only one species, N. fowleri, causes an acute and fulminating meningoencephalitis in DOI:10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00232.x immunocompetent children and young adults. In addition to human infections, Editor: Willem van Leeuwen Acanthamoeba, Balamuthia and Naegleria can cause central nervous system infections in animals. Because only one human case of encephalitis caused by Keywords Sappinia diploidea is known, generalizations about the organism as an agent of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis; disease are premature. -

Hung:Makieta 1.Qxd

DOI: 10.2478/s11686-013-0155-5 © W. Stefan´ski Institute of Parasitology, PAS Acta Parasitologica, 2013, 58(3), 231–258; ISSN 1230-2821 INVITED REVIEW Global status of fish-borne zoonotic trematodiasis in humans Nguyen Manh Hung1, Henry Madsen2* and Bernard Fried3 1Department of Parasitology, Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, 18 Hoang Quoc Viet, Hanoi, Vietnam; 2Department of Veterinary Disease Biology, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Thorvaldsensvej 57, 1871 Frederiksberg C, Denmark; 3Department of Biology, Lafayette College, Easton, PA 18042, United States Abstract Fishborne zoonotic trematodes (FZT), infecting humans and mammals worldwide, are reviewed and options for control dis- cussed. Fifty nine species belonging to 4 families, i.e. Opisthorchiidae (12 species), Echinostomatidae (10 species), Hetero- phyidae (36 species) and Nanophyetidae (1 species) are listed. Some trematodes, which are highly pathogenic for humans such as Clonorchis sinensis, Opisthorchis viverrini, O. felineus are discussed in detail, i.e. infection status in humans in endemic areas, clinical aspects, symptoms and pathology of disease caused by these flukes. Other liver fluke species of the Opisthorchiidae are briefly mentioned with information about their infection rate and geographical distribution. Intestinal flukes are reviewed at the family level. We also present information on the first and second intermediate hosts as well as on reservoir hosts and on habits of human eating raw or undercooked fish. Keywords Clonorchis, Opisthorchis, intestinal trematodes, liver trematodes, risk factors Fish-borne zoonotic trematodes with feces of their host and the eggs may reach water sources such as ponds, lakes, streams or rivers. -

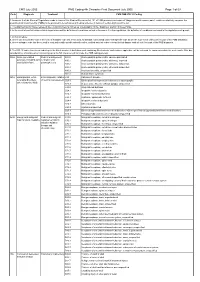

CMS PMB ICD-10 Coding

CMS July 2005 PMB Coding 4th Character Final Dcoument July 2005 Page 1 of 69 Code Diagnosis Treatment CMS PMB ICD-10 Coding 1. Annexure A of the General Regulations made in terms of the Medical Schemes Act, 131 of 1998 provides a schedule of “diagnosis and treatment pairs”, which cumulatively comprise the prescribed minimum benefits (PMBs) to be provided to beneficiaries of medical schemes in terms of section 29(1)(o) of the Act. 2. The attached ICD10 codes represent the Council for Medical Schemes’ interpretation of the “diagnosis” portion of these PMBs. 3. In the event of conflict between this interpretation and the definition of conditions set out in Annexure A to the regulations, the definition of conditions contained in the regulations will prevail. 4. In this schedule: a. where only the primary code in the form of a dagger code has been used, all asterisk codes listed under that specific code as per the ICD-10 set of books form part of the PMB diagnosis; b. where a dagger code has been used in conjunction with specific asterisk codes, omitted asterisk codes relevant to that dagger code do not form part of the PMB diagnosis. 5. The ICD-10 codes have been coded up to the 4th character. A draft document containing 5th character codes where applicable, will be released for comments within the next month. After due consideration, a final document containing up to the 5th character will conclude the PMB coding process. 906A Acute generalised Medical management; A80.0 Acute paralytic poliomyelitis, vaccine-associated paralysis, including -

2011/109440 Al

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date _ . 9 September 2011 (09.09.2011) 2011/109440 Al (51) International Patent Classification: [CH/CH]; Chemin Des Chevreuils 1, 1188 Gimel (CH). C12Q 1/68 (2006.01) G01N 33/53 (2006.01) HOLTERMAN, Daniel [US/US]; 14465 North 14th St., Phoenix, AZ 85022 (US). (21) International Application Number: PCT/US201 1/026750 (74) Agent: AKHAVAN, Ramin; Caris Life Sciences, Inc., 6655 N. MacArthur Blvd., Irving, TX 75039 (US). (22) International Filing Date: 1 March 201 1 (01 .03.201 1) (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, English (25) Filing Language: AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, (26) Publication Language: English CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (30) Priority Data: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, 61/274,124 1 March 2010 (01 .03.2010) US KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, 61/357,5 17 22 June 2010 (22.06.2010) US ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, 61/364,785 15 July 2010 (15.07.2010) us NO, NZ, OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, RO, RS, RU, SC, SD, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): CARIS SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, LIFE SCIENCES LUXEMBOURG HOLDINGS [LU/ TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. -

The Epidemiology and Clinical Features of Balamuthia Mandrillaris Disease in the United States, 1974 – 2016

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Clin Infect Manuscript Author Dis. Author manuscript; Manuscript Author available in PMC 2020 August 28. Published in final edited form as: Clin Infect Dis. 2019 May 17; 68(11): 1815–1822. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy813. The Epidemiology and Clinical Features of Balamuthia mandrillaris Disease in the United States, 1974 – 2016 Jennifer R. Cope1, Janet Landa1,2, Hannah Nethercut1,3, Sarah A. Collier1, Carol Glaser4, Melanie Moser5, Raghuveer Puttagunta1, Jonathan S. Yoder1, Ibne K. Ali1, Sharon L. Roy6 1Waterborne Disease Prevention Branch, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA 2James A. Ferguson Emerging Infectious Diseases Fellowship Program, Baltimore, MD, USA 3Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education, Oak Ridge, TN, USA 4Kaiser Permanente, San Francisco, CA, USA 5Office of Financial Resources, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Atlanta, GA, USA 6Parasitic Diseases Branch, Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria, Center for Global Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA Abstract Background—Balamuthia mandrillaris is a free-living ameba that causes rare, nearly always fatal disease in humans and animals worldwide. B. mandrillaris has been isolated from soil, dust, and water. Initial entry of Balamuthia into the body is likely via the skin or lungs. To date, only individual case reports and small case series have been published. Methods—The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) maintains a free-living ameba (FLA) registry and laboratory. To be entered into the registry, a Balamuthia case must be laboratory-confirmed. -

The Draft Genome of the Carcinogenic Human Liver Fluke Clonorchis Sinensis

Wang et al. Genome Biology 2011, 12:R107 http://genomebiology.com/2011/12/10/R107 RESEARCH Open Access The draft genome of the carcinogenic human liver fluke Clonorchis sinensis Xiaoyun Wang1,2, Wenjun Chen1,2, Yan Huang1,2, Jiufeng Sun1,2, Jingtao Men1,2, Hailiang Liu3, Fang Luo3, Lei Guo3, Xiaoli Lv1,2, Chuanhuan Deng1,2, Chenhui Zhou1,2, Yongxiu Fan1,2, Xuerong Li1,2, Lisi Huang1,2, Yue Hu1,2, Chi Liang1,2, Xuchu Hu1,2, Jin Xu1,2 and Xinbing Yu1,2* Abstract Background: Clonorchis sinensis is a carcinogenic human liver fluke that is widespread in Asian countries. Increasing infection rates of this neglected tropical disease are leading to negative economic and public health consequences in affected regions. Experimental and epidemiological studies have shown a strong association between the incidence of cholangiocarcinoma and the infection rate of C. sinensis. To aid research into this organism, we have sequenced its genome. Results: We combined de novo sequencing with computational techniques to provide new information about the biology of this liver fluke. The assembled genome has a total size of 516 Mb with a scaffold N50 length of 42 kb. Approximately 16,000 reliable protein-coding gene models were predicted. Genes for the complete pathways for glycolysis, the Krebs cycle and fatty acid metabolism were found, but key genes involved in fatty acid biosynthesis are missing from the genome, reflecting the parasitic lifestyle of a liver fluke that receives lipids from the bile of its host. We also identified pathogenic molecules that may contribute to liver fluke-induced hepatobiliary diseases. -

A Parasitological Evaluation of Edible Insects and Their Role in the Transmission of Parasitic Diseases to Humans and Animals

RESEARCH ARTICLE A parasitological evaluation of edible insects and their role in the transmission of parasitic diseases to humans and animals 1 2 Remigiusz GaøęckiID *, Rajmund Soko ø 1 Department of Veterinary Prevention and Feed Hygiene, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Warmia and Mazury, Olsztyn, Poland, 2 Department of Parasitology and Invasive Diseases, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Warmia and Mazury, Olsztyn, Poland a1111111111 a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract From 1 January 2018 came into force Regulation (EU) 2015/2238 of the European Parlia- ment and of the Council of 25 November 2015, introducing the concept of ªnovel foodsº, including insects and their parts. One of the most commonly used species of insects are: OPEN ACCESS mealworms (Tenebrio molitor), house crickets (Acheta domesticus), cockroaches (Blatto- Citation: Gaøęcki R, SokoÂø R (2019) A dea) and migratory locusts (Locusta migrans). In this context, the unfathomable issue is the parasitological evaluation of edible insects and their role in the transmission of parasitic diseases to role of edible insects in transmitting parasitic diseases that can cause significant losses in humans and animals. PLoS ONE 14(7): e0219303. their breeding and may pose a threat to humans and animals. The aim of this study was to https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219303 identify and evaluate the developmental forms of parasites colonizing edible insects in Editor: Pedro L. Oliveira, Universidade Federal do household farms and pet stores in Central Europe and to determine the potential risk of par- Rio de Janeiro, BRAZIL asitic infections for humans and animals. -

Epicrates Cenchria Cenchria (Squamata: Boidae) by Porocephalus (Pentastomida: Porocephalidae) in Ecuador Biota Colombiana, Vol

Biota Colombiana ISSN: 0124-5376 [email protected] Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos "Alexander von Humboldt" Colombia Pozo-Zamora, Glenda M.; Yánez-Muñoz, Mario H. First infestation record of Epicrates cenchria cenchria (Squamata: Boidae) by Porocephalus (Pentastomida: Porocephalidae) in Ecuador Biota Colombiana, vol. 20, no. 1, 2019, January-June, pp. 120-125 Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos "Alexander von Humboldt" Colombia DOI: https://doi.org/10.21068/c2019.v20n01a08 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=49159822008 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Pozo-Zamora & Yánez-Muñoz Infestation of Epicrates cenchria cenchria by Porocephalus Nota First infestation record of Epicrates cenchria cenchria (Squamata: Boidae) by Porocephalus (Pentastomida: Porocephalidae) in Ecuador Primer registro de infestación de Epicrates cenchria cenchria (Squamata: Boidae) por Porocephalus (Pentastomida: Porocephalidae) en Ecuador Glenda M. Pozo-Zamora and Mario H. Yánez-Muñoz Abstract Endoparasites of the genus Porocephalus, which mainly affect lungs of snakes, are distributed in Asia, Africa and America. In Ecuador, these parasites have been reported only for Boa constrictor. Here, we report the first record of infestation of Porocephalus in Epicrates cenchria cenchria from the Ecuadorian Amazon, based on examination of museum specimens. We found 26 parasitic individuals in 4 infected snakes, with a maximum of 16 individuals in a juvenile snake, and a minimum of 2 in an adult snake. Morphometric characters of the Ecuadorian populations of Porocephalus do not agree with those described for the genus. -

Liver Fluke Induces Cholangiocarcinoma

Neglected Diseases Liver Fluke Induces Cholangiocarcinoma Banchob Sripa*, Sasithorn Kaewkes, Paiboon Sithithaworn, Eimorn Mairiang, Thewarach Laha, Michael Smout, Chawalit Pairojkul, Vajaraphongsa Bhudhisawasdi, Smarn Tesana, Bandit Thinkamrop, Jeffrey M. Bethony, Alex Loukas, Paul J. Brindley* Opisthorchiasis and Clonorchiasis: Major Regional Public Health Problems Liver fl uke infection caused by Opisthorchis viverrini, O. felineus, and Clonorchis sinensis is a major public health problem in East Asia and Eastern Europe. Currently, more than 600 million people are at risk of infection with these trematodes [1]. O. viverrini is endemic in Southeast Asian countries, including Thailand, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Vietnam, and Cambodia [2], and C. sinensis infection is common in rural areas of Korea and China. Opisthorchiasis has been extensively studied in Thailand, where an estimated 6 million people are infected with the liver fl uke (calculated from overall 9.4% prevalence within the population in 2001) [3]. Infection with these food-borne parasites is prevalent in areas where uncooked cyprinoid fi sh are a staple of the diet. Due to poor sanitation practices and inadequate sewerage infrastructure, people infected with O. viverrini and C. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040201.g001 sinensis pass parasite eggs in their faeces into natural water Koi-Pla reservoirs, where the parasite eggs are eaten by intermediate Figure 1. Preparation of a Meal of Using Uncooked Cyprinoid Fishes host snails, for example, aquatic snails of the genus Bithynia, O. viverrini (A) Fluke-infected fi sh are plentiful in the local rivers such as the Chi the fi rst intermediate host of . After hatching, free River in Khon Kaen province, Thailand.