Three-Year Survey of Schools' Use of Off-Site Alternative Provision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Addendum to School Places Strategy 2017-2022 – Explanation of the Differences Between Wiltshire Community Areas and Wiltshire School Planning Areas

Addendum to School Places Strategy 2017-2022 – Explanation of the differences between Wiltshire Community Areas and Wiltshire School Planning Areas This document should be read in conjunction with the School Places Strategy 2017 – 2022 and provides an explanation of the differences between the Wiltshire Community Areas served by the Area Boards and the School Planning Areas. The Strategy is primarily a school place planning tool which, by necessity, is written from the perspective of the School Planning Areas. A School Planning Area (SPA) is defined as the area(s) served by a Secondary School and therefore includes all primary schools in the towns and surrounding villages which feed into that secondary school. As these areas can differ from the community areas, this addendum is a reference tool to aid interested parties from the Community Area/Area Board to define which SPA includes the schools covered by their Community Area. It is therefore written from the Community Area standpoint. Amesbury The Amesbury Community Area and Area Board covers Amesbury town and surrounding parishes of Tilshead, Orcheston, Shrewton, Figheldean, Netheravon, Enford, Durrington (including Larkhill), Milston, Bulford, Cholderton, Wilsford & Lake, The Woodfords and Great Durnford. It encompasses the secondary schools The Stonehenge School in Amesbury and Avon Valley College in Durrington and includes primary schools which feed into secondary provision in the Community Areas of Durrington, Lavington and Salisbury. However, the School Planning Area (SPA) is based on the area(s) served by the Secondary Schools and covers schools in the towns and surrounding villages which feed into either The Stonehenge School in Amesbury or Avon Valley College in Durrington. -

KS5 Transition Information Thinking Beyond Bonus Pastor: a Student Guide

Name: ____________________ KS5 Transition Information Thinking Beyond Bonus Pastor: A Student Guide Ms Hill – Leader of CEIAG and KS5 Transition [email protected] Today you have taken part in a KS5 Transition Meeting which I hope that you found interesting and insightful. The aim of this meeting was to get you thinking beyond Bonus Pastor. You will receive a copy of the Personal Action Plan that we created together in the meeting. Keep this together with the attached information, and use it to help guide you through the KS5 Transition process. If you or your parents/carers have any questions at any time, please email me – no question is a silly question! Qualifications Explained – What Can I Apply For? You are currently studying for GCSEs which are Level 1 or 2 qualifications, depending on what grades you achieve at the end of Year 11. Generally speaking: if you are forecast to achieve GCSEs at grades 1 - 4 then you can apply for Level 1 or 2 BTEC courses or an intermediate level apprenticeship. Once you have completed this you can progress to Level 3 courses. if you are forecast to achieve GCSEs at grades 4 or above then you can apply to study A Levels, Level 3 BTEC courses, or intermediate level or advanced level apprenticeships. (Most A Level courses will require you to have at least a grade 5 or 6 in the subjects you wish to study.) However if you are applying for a vocational trade-based course such as Hair and Beauty, Motor Vehicle Mechanics or Electrical Installation, all courses start at Level 1 and then progress up to Level 2 and 3 courses. -

Pyramid School Name Pyramid School Name Airedale Academy the King's School Airedale Junior School Halfpenny Lane JI School Fairb

Wakefield District School Names Pyramid School Name Pyramid School Name Airedale Academy The King's School Airedale Junior School Halfpenny Lane JI School Fairburn View Primary School Orchard Head JI School Airedale King's Oyster Park Primary School St Giles CE Academy Townville Infant School Ackworth Howard CE (VC) JI School Airedale Infant School Larks Hill JI School Carleton Community High School De Lacy Academy Cherry Tree Academy Simpson's Lane Academy De Lacy Primary School St Botolph's CE Academy Knottingley Carleton Badsworth CE (VC) JI School England Lane Academy Carleton Park JI School The Vale Primary Academy The Rookeries Carleton JI School Willow Green Academy Darrington CE Primary School Minsthorpe Community College Castleford Academy Carlton JI School Castleford Park Junior Academy South Kirkby Academy Glasshoughton Infant Academy Common Road Infant School Minsthorpe Half Acres Primary Academy Upton Primary School Castleford Smawthorne Henry Moore Primary School Moorthorpe Primary School Three Lane Ends Academy Northfield Primary School Ackton Pastures Primary Academy Ash Grove JI School Wheldon Infant School The Freeston Academy Cathedral Academy Altofts Junior School Snapethorpe Primary School Normanton All Saints CE (VA) Infant School St Michael's CE Academy Normanton Junior Academy Normanton Cathedral Flanshaw JI School Lee Brigg Infant School Lawefield Primary School Martin Frobisher Infant School Methodist (VC) JI School Newlands Primary School The Mount JI School Normanton Common Primary Academy Wakefield City Academy -

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey College Birmingham 873/4603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ramsey 865/4000 Abbeyfield School Chippenham 803/4000 Abbeywood Community School Bristol 860/4500 Abbot Beyne School Burton-on-Trent 312/5409 Abbotsfield School Uxbridge 894/6906 Abraham Darby Academy Telford 202/4285 Acland Burghley School London 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 825/6015 Akeley Wood Senior School Buckingham 935/4059 Alde Valley School Leiston 919/6003 Aldenham School Borehamwood 891/4117 Alderman White School and Language College Nottingham 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 830/4001 Alfreton Grange Arts College Alfreton 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 340/4615 All Saints Catholic High School Knowsley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College of Arts Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 380/6907 Appleton Academy Bradford 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 208/5403 Archbishop Tenison's School London 916/4032 Archway School Stroud 845/4003 ARK William Parker Academy Hastings 371/4021 Armthorpe Academy Doncaster 885/4008 Arrow Vale RSA Academy Redditch 937/5401 Ash Green School Coventry 371/4000 Ash Hill Academy Doncaster 891/4009 Ashfield Comprehensive School Nottingham 801/4030 Ashton -

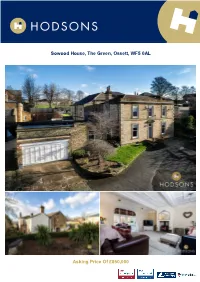

Sowood House, the Green, Ossett, WF5 0AL Asking Price of £850,000

Sowood House, The Green, Ossett, WF5 0AL Asking Price Of £850,000 Property Description ACCOMMODATION Sowood House, Ossett is one of the areas most historic properties, parts of which are believed be early 18th Century but for many years was used a s a Doctors surgery. The well appointed accommodation is set over 4000 sq/ft and the current owners have used the front portion of the property as a successful beauty salon and spa for the past 16 years. To the rear is the living accommodation, in itself a more than substantial family home which is tastefully presented throughout. The house is full of character, in keeping with the period including a truly spectacular full height inner reception hall with magnificent staircase. Other features of note include; sash windows with shutters, deep skirting boards and decorative ceilings. To the outside a secure electric gate gives access to a large drive providing significant off road parking. There is an inner courtyard area and a spacious rear garden tiered over two levels. It is likely the new owners will view Sowood House as an opportunity to develop into a property of their own choice and the options are endless. Whilst the commercial element could continue for a variety of uses, subject to planning consent the house could be reconverted in to one single dwelling or alternatively giving the opportunity to bring two families together in their own self-contained and substantial living space. FLOOR AREA Approximately 4600 sq/ft. Plot size: 0.39 acres COUNCIL TAX Wakefield MDC Band D with an average annual cost of £1,754.06. -

The Parish Church of S Giles with S Peter, Aintree

The Parish Church of S Giles with S Peter, Aintree Within the Anglican Diocese of Liverpool Parish Profile S Giles with S Peter, Aintree Lane, Aintree, Liverpool www.stgilesaintree.co.uk Contents About Aintree ....................................................................................................... 1 Facilities in Aintree ............................................................................................. 3 Getting About ...................................................................................................... 5 The History of Our Church .............................................................................. 6 Our Church Today .............................................................................................. 8 Our Services ........................................................................................................12 Our Congregation and Officers ..................................................................14 The Vicarage .......................................................................................................16 The S Giles Centre ............................................................................................18 Our Next Minister .............................................................................................22 St Giles, Aintree, Liverpool Parish Profile About Aintree Aintree is a village and civil parish in the Metropolitan Borough of Sefton, Merseyside. It lies between Walton and Maghull on the A59 road, about 6.5 miles (10.5 -

Greig City Academy High Street, Hornsey, London N8 7NU

School report Greig City Academy High Street, Hornsey, London N8 7NU Inspection dates 8–9 December 2015 Overall effectiveness Good Effectiveness of leadership and management Good Quality of teaching, learning and assessment Good Personal development, behaviour and welfare Good Outcomes for pupils Good 16 to 19 study programmes Good Overall effectiveness at previous inspection Good Summary of key findings for parents and pupils This is a good school The Principal and the governing body have high The academy is a harmonious, diverse and caring aspirations for all pupils. They have an accurate community where pupils are known well and feel understanding of the academy’s strengths and very safe. Staff receive relevant child protection areas for further development. training and appropriate procedures are Governors were quick to challenge academy consistently followed. Safeguarding is therefore, leaders about the 2015 GCSE results which, in effective. some subject areas, were disappointing. Leaders Pupils’ behaviour at the academy is good. They have taken decisive action. support each other’s learning in class, work hard New staff in key roles have swiftly secured and respect each other. Pupils mix well together improvements in teaching. Teaching in most at break and lunchtimes. subjects is now ensuring pupils make good The large and inclusive sixth form is good. It progress from often very low starting points. offers a range of appropriate courses, taught Staff at the academy understand the academic within a supportive and well-equipped and emotional needs of individual pupils. They environment. Pupils have high aspirations for offer high-quality support and guidance which future employment and studies, and they receive pupils value highly. -

Harris Free School Tottenham 2

Free Schools in 2013 Application form Mainstream and 16-19 Free Schools Completing your application Before completing your application, please ensure that you have read the ‘How to Apply’ guidance carefully (which can be found here) and can provide all the information and documentation we have asked for – failure to do so may mean that we are unable to consider your application. The Free School application is made up of nine sections as follows: Section A: Applicant details and declaration Section B: Outline of the school Section C: Education vision Section D: Education plan Section E: Evidence of demand and marketing Section F: Capacity and capability Section G: Initial costs and financial viability Section H: Premises Section I: Due diligence and other checks In Sections A-H we are asking you to tell us about you and the school you want to establish and this template has been designed for this purpose. The boxes provided in each section will expand as you type. Section G requires you to provide two financial plans. To achieve this you must fill out and submit the templates provided here. Section I is about your suitability to run a Free School. There is a separate downloadable form for this information. This is available here You need to submit all the information requested in order for your application to be assessed. Sections A-H and the financial plans need to be submitted to the Department for Education by the application deadline. You need to submit one copy (of each) by email to:[email protected]. -

AMP SCITT Ofsted Report 2017

Associated Merseyside Partnership SCITT Initial teacher education inspection report Inspection dates Stage 1: 12 June 2017 Stage 2: 13 November 2017 This inspection was carried out by one of Her Majesty’s Inspectors (HMI) and Ofsted Inspectors (OIs) in accordance with the ‘Initial teacher education inspection handbook’. This handbook sets out the statutory basis and framework for initial teacher education (ITE) inspections in England from September 2015. The inspection draws on evidence from each phase within the ITE partnership to make judgements against all parts of the evaluation schedule. Inspectors focused on the overall effectiveness of the ITE partnership in securing high-quality outcomes for trainees. Inspection judgements Key to judgements: Grade 1 is outstanding; grade 2 is good; grade 3 is requires improvement; grade 4 is inadequate Primary and secondary QTS Overall effectiveness How well does the partnership secure 2 consistently high-quality outcomes for trainees? The outcomes for trainees 2 The quality of training across the 2 partnership The quality of leadership and management across the 2 partnership Primary and secondary routes Information about this ITE partnership The Associated Merseyside Partnership school-centred initial teacher training (SCITT) began in September 2015. It forms part of the Lydiate Learning Trust, with Deyes High School as lead school in the partnership for the secondary phase. There is currently no lead school for the primary phase. Within the partnership, there are 13 secondary schools across four local authorities, and 12 primary schools all within the same local authority. In addition, there are two all-through schools catering for pupils in the three-to-19 age range across two local authorities. -

School Fires List 2019.Xlsx

Date and Time Of Call Calendar Year Property Type Description Organisation Name Description2 Street PostCode Borough Name 17/01/2019 11:47 2019 Infant/Primary school EDGWARE PRIMARY SCHOOL EDGWARE PRIMARY SCHOOL HEMING ROAD HA8 9AB Barnet 17/01/2019 14:30 2019 Pre School/nursery MARLBOROUGH PRIMARY SCHOOL MARLBOROUGH PRIMARY SCHOOL LONDON ROAD TW7 5XA Hounslow 30/01/2019 18:04 2019 College/University NEWINGTON BUTTS SE11 4FL Southwark 31/01/2019 08:26 2019 Infant/Primary school BRAINTCROFT PRIMARY SCHOOL WARREN ROAD NW2 7LL Brent 04/02/2019 13:02 2019 Secondary school CLEEVE PARK SCHOOL CLEEVE PARK SCHOOL BEXLEY LANE DA14 4JN Bexley 05/02/2019 10:25 2019 Pre School/nursery EASTERN ROAD RM1 3QA Havering 06/02/2019 08:40 2019 Secondary school BENTLEY WOOD HIGH SCHOOL TEMPORARY CLASSROOMS SITE OF TEMPORARY SINGLE STORBINYON CRESCENT HA7 3NA Harrow 07/02/2019 21:12 2019 College/University SOCIAL EDUCATION CENTRE WESTMINSTER ADULT EDUCATION SERVICE LISSON GROVE NW8 8LW Westminster 09/02/2019 09:46 2019 College/University WORKING MENS COLLEGE W M C CROWNDALE ROAD NW1 1TR Camden 11/02/2019 07:55 2019 Infant/Primary school GRASVENOR AVENUE INFANT SCHOOL GRASVENOR AVENUE INFANT SCHOOL GRASVENOR AVENUE EN5 2BY Barnet 11/02/2019 10:36 2019 College/University HULT BUSINESS SCHOOL RUSSELL SQUARE WC1B 4JP Camden 11/02/2019 14:35 2019 Secondary school EMANUEL SCHOOL EMANUEL SCHOOL BATTERSEA RISE SW11 1HS Wandsworth 14/02/2019 15:03 2019 Secondary school CHISWICK COMMUNITY SCHOOL BURLINGTON LANE W4 3UN Hounslow 14/02/2019 16:09 2019 Infant/Primary school -

Going to School in Nottingham 2013/142017/18 Information About A

Going to school in Nottingham 2013/142017/18 Information about a Appendix 1 – admission criteria for secondary schools and academies in Nottingham City Admission criteria for secondary schools and academies in Nottingham City. The following pages set out the admission criteria for the 2017/18 school year for each secondary school and academy in Nottingham City. If a school receives more applications than it has places available, this means the school is oversubscribed and places are offered using the school’s admission criteria. The table below lists the secondary schools and academies in Nottingham City: School/academy name Type of school Bluecoat Academy Voluntary Aided Academy Bluecoat Beechdale Academy Academy The Bulwell Academy Academy Djanogly City Academy Academy Ellis Guilford School & Sports College Community The Farnborough Academy Academy The Fernwood School Academy Nottingham Academy Academy The Nottingham Emmanuel School Voluntary Aided Academy Nottingham Free School Free School Nottingham Girls' Academy Academy Nottingham University Academy of Science & Technology 14-19 Academy Nottingham University Samworth Academy Academy The Oakwood Academy Academy Top Valley Academy Academy The Trinity Catholic School Voluntary Aided Academy For a list of the secondary schools and academies oversubscribed at the closing date in year 7 in the 2016/17 school year, see page 23 of the ‘Going to School in Nottingham 2017/18’ booklet; and for information regarding school/academy addresses, contact details for admission enquiries, etc. see pages 66 to 68 of the booklet. Admissions Policy 2017/18 Bluecoat Church of England Academy Bluecoat Academy offers an all though education from age 4 – 19. The Academy is both distinctively Christian and inclusive. -

ACADEMY and VOLUNTARY AIDED SCHOOLS ADMINISTERED by DEMOCRATIC SERVICES – August 2021

ACADEMY AND VOLUNTARY AIDED SCHOOLS ADMINISTERED BY DEMOCRATIC SERVICES – August 2021 Primary Schools:‐ Secondary Schools:‐ Abbey Primary School (Mansfield) (5 – 11 Academy) The Alderman White School (11‐18) Abbey Road Primary School (Rushcliffe) ‐ Academy (5 – 11 Academy) Ashfield School (11 – 18) All Saints Primary, Newark (5 – 11 Voluntary Aided) Bramcote College (11‐18) Bracken Lane Primary Academy (5 – 11 Academy) Chilwell School (11‐18) Brookside Primary (5 – 11 Academy) East Leake Academy (11 – 18) Burntstump Seely Church of England Primary Academy (5 – 11) Magnus Church of England Academy (11 – 18) Burton Joyce Primary (5 – 11 Academy) Manor Academy (11‐18) Cropwell Bishop Primary (5 – 11 Academy) Outwood Academy Portland (11 – 18) Crossdale Drive Primary (5 – 11 Academy) Outwood Academy Valley (11 – 18) Flintham Primary (5 – 11 Academy) Quarrydale Academy (11 – 18) Haggonfields Primary School (3‐11) Queen Elizabeth’s Academy (11 – 18) Harworth Church of England Academy (4‐11) Retford Oaks Academy (11 – 18) Heymann Primary (5 – 11 Academy) Samworth Church Academy Hillocks Primary ‐ Academy (5 – 11 Academy) Selston High School (11 – 18) Hucknall National C of E Primary (5 – 11 Academy) The Garibaldi School (11‐18) John Clifford Primary School (5 – 11 Academy) The Fernwood School (11‐ 18) (City School) Keyworth Primary and Nursery (5 – 11 Academy) The Holgate Academy (11 – 18) Langold Dyscarr Community School (3‐11) The Meden SAchool (11 – 18) Larkfields Junior School (7 – 11 Foundation) The Newark Academy (11 – 18) Norbridge Academy