Country of Origin Information on the Situation in the Gaza Strip, Including on Restrictions on Exit and Return

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West Bank and Gaza 2020 Human Rights Report

WEST BANK AND GAZA 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Palestinian Authority basic law provides for an elected president and legislative council. There have been no national elections in the West Bank and Gaza since 2006. President Mahmoud Abbas has remained in office despite the expiration of his four-year term in 2009. The Palestinian Legislative Council has not functioned since 2007, and in 2018 the Palestinian Authority dissolved the Constitutional Court. In September 2019 and again in September, President Abbas called for the Palestinian Authority to organize elections for the Palestinian Legislative Council within six months, but elections had not taken place as of the end of the year. The Palestinian Authority head of government is Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayyeh. President Abbas is also chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization and general commander of the Fatah movement. Six Palestinian Authority security forces agencies operate in parts of the West Bank. Several are under Palestinian Authority Ministry of Interior operational control and follow the prime minister’s guidance. The Palestinian Civil Police have primary responsibility for civil and community policing. The National Security Force conducts gendarmerie-style security operations in circumstances that exceed the capabilities of the civil police. The Military Intelligence Agency handles intelligence and criminal matters involving Palestinian Authority security forces personnel, including accusations of abuse and corruption. The General Intelligence Service is responsible for external intelligence gathering and operations. The Preventive Security Organization is responsible for internal intelligence gathering and investigations related to internal security cases, including political dissent. The Presidential Guard protects facilities and provides dignitary protection. -

Gaza Crossings' Operations Status: Monthly

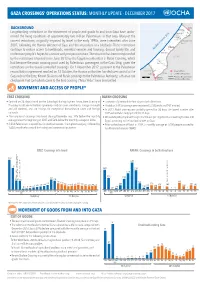

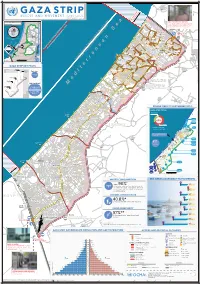

GAZA CROSSINGS’ OPERATIONS STATUS: MONTHLY UPDATE - DECEMBER 2017 BACKGROUND Erez Beit Lahiya ¹ ! Longstanding restrictions on the movement of people and goods to and from Gaza have under- ! Jabalya ! Beit Hanoun mined the living conditions of approximately two million Palestinians in that area. Many of the Gaza City ! n Sea ! Ash Shuja’iyeh current restrictions, originally imposed by Israel in the early 1990s, were intensified after June anea Nahal Oz Karni 2007, following the Hamas takeover of Gaza and the imposition of a blockade. These restrictions iterr GAZA Med 21 continue to reduce access to livelihoods, essential services and housing, disrupt family life, and 30! 0 undermine people’s hopes for a secure and prosperous future. The situation has been compounded Deir al B alah by the restrictions imposed since June 2013 by the Egyptian authorities at Rafah Crossing, which ISRAEL ! had become the main crossing point used by Palestinian passengers in the Gaza Strip, given the Khan Yunis Khuza’a ! restrictions on the Israeli-controlled crossings. On 1 November 2017, pursuant to the Palestinian 14389 Rafah EGYPT ! Crossing Point reconciliation agreement reached on 12 October, the Hamas authorities handed over control of the Sufa Rafah¹º» Closed Crossing Point Armistice Declaration Line Gaza side of the Erez, Kerem Shalom and Rafah crossings to the Palestinian Authority; a Hamas-run 5 Km ¹º» Kerem checkpoint that controlled access to the Erez crossing (“Arba’ Arba’”) was dismantled. Shalom International Boundary MOVEMENT AND ACCESS OF PEOPLE* EREZ CROSSING RAFAH CROSSING • Opened on 26 days (closed on five Saturdays) during daytime hours, from Sunday to • Exceptionally opened for four days in both directions. -

The Humanitarian Monitor CAP Occupied Palestinian Territory Number 17 September 2007

The Humanitarian Monitor CAP occupied Palestinian territory Number 17 September 2007 Overview- Key Issues Table of Contents Update on Continued Closure of Gaza Key Issues 1 - 2 Crossings Regional Focus 3 Access and Crossings Rafah and Karni crossings remain closed after more than threemonths. Protection of Civilians 4 - 5 The movement of goods via Gaza border crossings significantly Child Protection 6-7 declined in September compared to previous months. The average Violence & Private 8-9 of 106 truckloads per day that was recorded between 19 June and Property 13 September has dropped to approximately 50 truckloads per day 10 - 11 since mid-September. Sufa crossing (usually opened 5 days a week) Access was closed for 16 days in September, including 8 days for Israeli Socio-economic 12 - 13 holidays, while Kerem Shalom was open only 14 days throughout Conditions the month. The Israeli Civil Liaison Administration reported that the Health 14 - 15 reduction of working hours was due to the Muslim holy month Food Security & 16 - 18 of Ramadan, Jewish holidays and more importantly attacks on the Agriculture crossings by Palestinian militants from inside Gaza. Water & Sanitation 19 Impact of Closure Education 20 As a result of the increased restrictions on Gaza border crossings, The Response 21 - 22 an increasing number of food items – including fruits, fresh meat and fish, frozen meat, frozen vegetables, chicken, powdered milk, dairy Sources & End Notes 23 - 26 products, beverages and cooking oil – are experiencing shortages on the local market. The World Food Programme (WFP) has also reported significant increases in the costs of these items, due to supply, paid for by deductions from overdue Palestinian tax increases in prices on the global market as well as due to restrictions revenues that Israel withholds. -

Guidelines on Human Rights Education for Health Workers Published by the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) Ul

guidelines on human rights education for health workers Published by the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) Ul. Miodowa 10 00–251 Warsaw Poland www.osce.org/odihr © OSCE/ODIHR 2013 All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be freely used and copied for educational and other non-commercial purposes, provided that any such reproduction is accompanied by an acknowledgement of the OSCE/ ODIHR as the source. ISBN 978-92-9234-870-0 Designed by Homework, Warsaw, Poland Cover photograph by iStockphoto Printed in Poland by Sungraf Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................ 5 FOreworD ................................................................................................... 9 Introduction ............................................................................................11 Rationale for human rights education for health workers............................. 11 Key definitions for the guidelines .............................................................................14 Process for elaborating the guidelines ................................................................... 15 Anticipated users of the guidelines .......................................................................... 17 Purposes of the guidelines ........................................................................................... 17 Application of the guidelines ......................................................................................18 -

Beneficiary and Community Perspectives on the Palestinian National Cash Transfer Programme

TRANSFORMING COUNTRY BRIEFING CASH TRANSFERS Beneficiary and community perspectives on the Palestinian National Cash Transfer Programme transformingcashtransfers.org Introduction transformingcashtransfers.org Our research aimed to explore the perceptions of cash transfer programme beneficiaries and implementers and other community members, in order to ensure their views are better reflected in policy and programming. Introduction transformingcashtransfers.org There is growing evidence internationally of positive links Key points: between social protection and poverty and vulnerability reduction. However, there has been limited recognition of the • De-developmental policies, recurring social inequalities that perpetuate poverty, such as gender insecurity and dependency on donor inequality, unequal citizenship status and displacement funding are among the key challenges through conflict, and the role social protection can play in in advancing social protection in the tackling these interlinked socio-political vulnerabilities. Occupied Palestinian Territories. • The Palestinian National Cash Transfer This country briefing synthesises qualitative research focusing Programme is an important but on beneficiary and community perceptions of the Palestinian limited component of female-headed National Cash Transfer Programme (PNCTP) in Gaza1 and households’ coping repertoires. West Bank2, as part of a broader research project in five countries (Kenya, Mozambique, OPT, Uganda and Yemen) by • Programme governance requires urgent the Overseas Development -

Palestinian Shot Near Rafah Crossing by ASSOCIATED PRESS EL-ARISH, Egypt

Palestinian shot near Rafah Crossing By ASSOCIATED PRESS EL-ARISH, Egypt Talkbacks for this article: 5 A Palestinian official at the Rafah border crossing with Gaza was wounded in shooting Friday that Egyptian security and border officials described as an assassination attempt. Mustafa Saad Jbour, a 25-year-old Palestinian officer on the Rafah checkpoint sustained several bullet wounds to the leg, Capt. Mohammed Badr of the Egyptian Sinai security service said. Badr said that Jbour, who was in hospital in the nearby El-Arish town, came under machine gun fire Friday evening in the Egyptian district, just a few hundreds meters (yards) from the Egypt-Gaza crossing, when masked militants in a speeding car sprayed him with bullets and fled the scene. The shooting came after Jbour had informed Egyptian authorities earlier in the week about uncovering a tunnel in the border city of Rafah, that allegedly was used to smuggle weapons and Palestinians from the Sinai Peninsula into Gaza. Hospital officials at El-Arish said that Jbour has lost a lot of blood and would be transferred to another hospital for surgery. Badr also said that the tunnel discovered by Jbour contained over 30,000 bullets and was located in the middle of a field, about 5 kilometers (3 miles) north of Rafah and within meters (yards) of the boundary. Egypt was coordinating with Palestinian authorities in Gaza to close the newly discovered tunnel from the other end, Badr added. Israel has long accused Egypt of not doing enough to stop the smuggling of weapons to Palestinian militants. -

Defeating Terror Promoting Peace ISRAEL MINISTRY of FOREIGN AFFAIRS

ISRAEL MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS Israel’s Operation against Hamas Defeating Terror Promoting Peace ISRAEL MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS 1 Moderates vs. Extremists The Struggle for Regional Peace Israel desires peace with those who seek peace, but must deter those who seek its destruction ISRAEL MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS Israel's greatest hope Signing the Israel-Jordan is to live in peace and security with all its neighbors Peace Treaty ISRAEL MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS Prime Minister Begin, President Sadat and Israel Prime Minister Ehud Olmert and Foreign Minister Livni meets with Qatar President Carter signing the Israel-Egypt Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas Prime Minister Hamad bin Jassem bin Jabr Al- Peace Treaty, Washington, 26 March 1979 with US President Bush at the Annapolis Thani at the 8th Doha Forum on Democracy, Conference, November 2007 Development, and Free Trade (April 2008) More info Foreign Minister Livni meets with Former Israel Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, MASHAV Course for Palestinian Farmers on Foreign Minister of Oman Yousef Bin Alawi US President George Bush and Palestinian Cooperative Development in Rural Areas Prime Minister Mahmoud Abbas Middle East summit in Aqaba (June 2003) Israel has proven its ability to make peace with those who desire peace. The moderates in the region agree on the need for a “two-state solution” to the Palestinian issue ISRAEL MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS Assad and Ahmadinejad Hamas in Gaza - September 2007 Ahmadinejad and Nasrallah While Israel desires peace with those who seek peace, -

Human Rights International Ngos: a Critical Evaluation

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law University at Buffalo School of Law Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law Contributions to Books Faculty Scholarship 2001 Human Rights International NGOs: A Critical Evaluation Makau Mutua University at Buffalo School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/book_sections Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Makau Mutua, Human Rights International NGOs: A Critical Evaluation in NGOs and Human Rights: Promise and Performance 151 (Claude E. Welch, Jr., ed., University of Pennsylvania Press 2001) Copyright © 2001 University of pennsylvania Press. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of scholarly citation, none of this work may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher. For information address the University of Pennsylvania Press, 3905 Spruce Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Contributions to Books by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chapter 7 Human Rights International NGOs A Critical Evaluation Makau Mutua The human rights movement can be seen in variety of guises. It can be seen as a move ment for international justice or as a cultural project for "civilizing savage" cultures. -

Human Rights Organisations on 5 Continents

FIDH represents 164 human rights organisations on 5 continents FIDH - International Federation for Human Rights 17, passage de la Main-d’Or - 75011 Paris - France CCP Paris: 76 76 Z Tel: (33-1) 43 55 25 18 / Fax: (33-1) 43 55 18 80 www.fi dh.org ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT 2011 Cover: © AFP/MOHAMMED ABED Egypt, 16 December 2011. 04 Our Fundamentals 06 164 member organisations 07 International Board 08 International Secretariat 10 Priority 1 Protect and support human rights defenders 15 Priority 2 Promote and protect women’s rights 19 Priority 3 Promote and protect migrants’ rights 24 Priority 4 Promote the administration of justice and the i ght against impunity 33 Priority 5 Strengthening respect for human rights in the context of globalisation 38 Priority 6 Mobilising the community of States 43 Priority 7 Support the respect for human rights and the rule of law in conl ict and emergency situations, or during political transition 44 > Asia 49 > Eastern Europe and Central Asia 54 > North Africa and Middle East 59 > Sub-Saharan Africa 64 > The Americas 68 Internal challenges 78 Financial report 2011 79 They support us Our Fundamentals Our mandate: Protect all rights Interaction: Local presence - global action The International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) is an As a federal movement, FIDH operates on the basis of interac- international NGO. It defends all human rights - civil, political, tion with its member organisations. It ensures that FIDH merges economic, social and cultural - as contained in the Universal on-the-ground experience and knowledge with expertise in inter- Declaration of Human Rights. -

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

Crossing and Constructing Borders Within Daily Contacts Cedric Parizot

Crossing and constructing borders within daily contacts Cedric Parizot To cite this version: Cedric Parizot. Crossing and constructing borders within daily contacts: Social and economic relations between the Bedouin in the Negev and their network in Gaza, the West Bank and Jordan. NOTES DE RECHERCHE DU CER, 2004, Aix en Provence. halshs-00080661 HAL Id: halshs-00080661 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00080661 Submitted on 20 Jun 2006 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. CENTRE D’ECONOMIE REGIONALE DE L'EMPLOI ET DES FIRMES INTERNATIONALES NOTES DE RECHERCHE DU CER CROSSING AND CONSTRUCTING BORDERS WITHIN DAILY CONTACTS: SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC RELATIONS BETWEEN THE BEDOUIN IN THE NEGEV AND THEIR NETWORKS IN GAZA, THE WEST BANK AND JORDAN N° 287 - 2004/10 Cédric PARIZOT CENTRE D'ECONOMIE REGIONALE, DE L'EMPLOI ET DES FIRMES INTERNATIONALES Faculté d’Economie Appliquée Université Paul Cézanne – Aix-Marseille III 15-19 allée Claude Forbin F-13627 Aix en Provence Cedex 1 Tél. : (0)4 42 21 60 11 - Fax : (0)4 42 23 08 94 E.mail : [email protected] -

Egypt and Israel: Tunnel Neutralization Efforts in Gaza

WL KNO EDGE NCE ISM SA ER IS E A TE N K N O K C E N N T N I S E S J E N A 3 V H A A N H Z И O E P W O I T E D N E Z I A M I C O N O C C I O T N S H O E L C A I N M Z E N O T Egypt and Israel: Tunnel Neutralization Efforts in Gaza LUCAS WINTER Open Source, Foreign Perspective, Underconsidered/Understudied Topics The Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, is an open source research organization of the U.S. Army. It was founded in 1986 as an innovative program that brought together military specialists and civilian academics to focus on military and security topics derived from unclassified, foreign media. Today FMSO maintains this research tradition of special insight and highly collaborative work by conducting unclassified research on foreign perspectives of defense and security issues that are understudied or unconsidered. Author Background Mr. Winter is a Middle East analyst for the Foreign Military Studies Office. He holds a master’s degree in international relations from Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and was an Arabic Language Flagship Fellow in Damascus, Syria, in 2006–2007. Previous Publication This paper was originally published in the September-December 2017 issue of Engineer: the Professional Bulletin for Army Engineers. It is being posted on the Foreign Military Studies Office website with permission from the publisher. FMSO has provided some editing, format, and graphics to this paper to conform to organizational standards.