Welsh Ambulance Services NHS Trust Submission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information for Candidates APPOINTMENT of NON

NHS Trust Non-executive Director Information for Candidates APPOINTMENT OF NON-EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF WELSH AMBULANCE SERVICES NHS TRUST NHS Trust Non-executive Director Diversity Statement The Welsh Government believes that public bodies should have board members who reflect Welsh society - people from all walks of life - to help them understand people's needs and make better decisions. This is why the Welsh Government is encouraging a wide and diverse range of individuals to apply for appointments to public bodies. Applications are particularly welcome from all under-represented groups including women, people under 30 years of age, members of ethnic minorities, disabled people, lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans people. Positive about Disability The Welsh Government operates a Positive about Disabled People scheme and welcome applications from people with disabilities. The scheme guarantees an interview to disabled people if they meet the minimum criteria for the post. The application form also enables you to detail any specific needs or equipment that you may need if invited to attend an interview. NHS Trust Non-executive Director Background and Context The Welsh Government’s vision for the NHS in Wales is “to create world-class health”. This vision is set out in Together for Health, and is based on providing more community services closer to home, alongside specialist centres of excellence, which give better results for patients. Who does what in the NHS in Wales? The Minister for Health and Social Services is responsible for all aspects of the NHS in Wales. Details of the Ministers responsibilities can be found here http://gov.wales/about/cabinet/cabinetm/markdrakeford The National Delivery Group, forms part of the Welsh Government’s Health and Social Services (HSSG) Group, and is responsible for overseeing the development and delivery of NHS services across Wales. -

NHS Wales Decarbonisation Strategic Delivery Plan

NHS Wales Decarbonisation Strategic Delivery Plan 2021-2030 (including Technical Appendices) Published March 2021 NHS Wales Decarbonisation Strategic Delivery Plan Who we are Established in 2001, the Carbon Trust works with businesses, governments and institutions around the world, helping them contribute to, and benefit from, a more sustainable future through carbon reduction, resource efficiency strategies, and commercialising low carbon businesses, systems and technologies. The Carbon Trust: • works with corporates and governments, helping them to align their strategies with climate science and meet the goals of the Paris Agreement; • provides expert advice and assurance, giving investors and financial institutions the confidence that green finance will have genuinely green outcomes; and • supports the development of low carbon technologies and solutions, building the foundations for the energy system of the future. Headquartered in London, the Carbon Trust has a global team of over 200 staff, representing over 30 nationalities, based across five continents. 1 NHS Wales Decarbonisation Strategic Delivery Plan The Carbon Trust’s mission is to accelerate the move to a sustainable, low carbon economy. It is a world leading expert on carbon reduction and clean technology. As a not-for-dividend group, it advises governments and leading companies around the world, reinvesting profits into its low carbon mission. The NHS Wales Shared Services Partnership (NWSSP) is an independent organisation, owned and directed by NHS Wales. NWSSP supports -

List of Licensed Organisations PDF Created: 29 09 2021

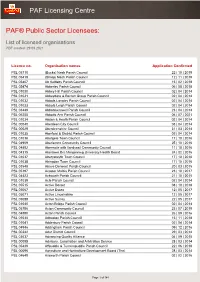

PAF Licensing Centre PAF® Public Sector Licensees: List of licensed organisations PDF created: 29 09 2021 Licence no. Organisation names Application Confirmed PSL 05710 (Bucks) Nash Parish Council 22 | 10 | 2019 PSL 05419 (Shrop) Nash Parish Council 12 | 11 | 2019 PSL 05407 Ab Kettleby Parish Council 15 | 02 | 2018 PSL 05474 Abberley Parish Council 06 | 08 | 2018 PSL 01030 Abbey Hill Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01031 Abbeydore & Bacton Group Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01032 Abbots Langley Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01033 Abbots Leigh Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 03449 Abbotskerswell Parish Council 23 | 04 | 2014 PSL 06255 Abbotts Ann Parish Council 06 | 07 | 2021 PSL 01034 Abdon & Heath Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 00040 Aberdeen City Council 03 | 04 | 2014 PSL 00029 Aberdeenshire Council 31 | 03 | 2014 PSL 01035 Aberford & District Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01036 Abergele Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04909 Aberlemno Community Council 25 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04892 Abermule with llandyssil Community Council 11 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04315 Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Board 24 | 02 | 2016 PSL 01037 Aberystwyth Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 01038 Abingdon Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 03548 Above Derwent Parish Council 20 | 03 | 2015 PSL 05197 Acaster Malbis Parish Council 23 | 10 | 2017 PSL 04423 Ackworth Parish Council 21 | 10 | 2015 PSL 01039 Acle Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 05515 Active Dorset 08 | 10 | 2018 PSL 05067 Active Essex 12 | 05 | 2017 PSL 05071 Active Lincolnshire 12 | 05 -

Integrated Medium Term Plan

1 CONTENTS Acronym Table 5 Message from the Chair and Chief Executive 8 Executive Summary 9 Part 1 Delivery of Our 2015/16 Plan 13 1.1 The New Clinical Response Model……………………………………............. 13 1.2 Quality and Operational Performance Trajectories…………………………... 15 1.3 2015/16 Strategic Change Portfolio …………………………………………… 18 1.4 Maturing Commissioning Arrangements and Increased Focus on Financial Strategy…………………………………………………………………………… 22 Part 2 Organisational and Strategic Context 24 This section, coupled with Part 1, serves as a high level diagnostic of the context within which we operate – it answers the “where are we now?” question. 2.1 Profile of the Trust……………………………………………………………….. 24 2.2 Our Demand & Activity………………………………………………………….. 32 2.3 The Five-Step Ambulance Care Pathway, Commissioning Quality & Delivery Framework, Understanding our Populations and Changes………. 33 2.4 National Policy Context………………………………………………………….. 37 2.5 Major Conditions, Older People and Frailty…………………………………… 42 2.6 Becoming a Listening and Learning Organisation………………………….... 43 2.7 NHS Wales Strategic Change Agenda………………………………………… 44 2.8 Service Change with Blue Light Partners……………………………………... 48 2.9 Ensuring Integration with Our Partners’ Three Year Plans………………….. 49 2.10 The Organisation and Prudent Healthcare……………………………………. 50 2.11 Treating People Fairly – Equality, Diversity & Human Rights………………. 51 2.12 Other Strategic Workforce and OD Drivers…………………………………… 54 Part 3 Creating Our Strategic Framework 57 This section sets the strategic framework for the organisation. It sets out our ambition and answers the “where do we want to go?” question. 3.1 Our Vision, Purpose and Behaviours………………………………………….. 57 3.2 Our Strategic Aims………………………………………………………………. 58 3.3 Our Priorities……………………………………………………………………… 59 3.4 Our Strategy Map………………………………………………………………… 63 3.5 Our Performance Ambitions………………………………………………........ -

{Department – Welsh}

Information Governance Team Vera Vallins Office Bronllys Hospital Bronllys Brecon Powys LD3 0LS Tel: 01874 712763 Fax: 01874 712756 Our ref: IG/FOI/19.R.233 23 September 2019 Sent via email to: [email protected] Dear Sir, Request under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 I write further to your request for information which was received on 29 August 2019 , to confirm, in accordance with S.1(1)(a) of the Freedom of Information Act 2000, that Powys Teaching Health Board (PTHB) holds part of the information that you require. For ease of reference your request is set out below and our response follows: Your Freedom of Information (FOI) Request: Who have you commissioned to provide any of the following orthotic devices which are vital to prevent damage and pain to the lower spine in long-term manual wheelchair users: 1. A measured spinal-restriction-brace, designed to stop long-term wheelchair users prevent stress induced damage and pain to their lumbar-sacrum region, where the spine joins the pelvis; 2. Power-assist motors such as: * Trike attachments * Pushers such as the Alber Smoov and Permobile Smart-drive * Joystick- and push-rim- controlled hub motors? 3. Please send me the minutes of the meetings discussing this essential support for wheelchair users, and a copy of the contract you commissioned. 4. If nothing has been commissioned, or if nothing has been considered for commissioning, what is the official protocol to get the consideration of such orthotic devices put onto the agenda? Is there a form members of the public can fill in? Pencadlys Headquarters Tŷ Glasbury, Ysbyty Bronllys, Glasbury House, Bronllys Hospital Aberhonddu, Powys LD3 0LU Brecon, Powys LD3 0LU Ffôn: 01874 711661 Tel: 01874 711661 Rydym yn croesawu gohebiaeth Gymraeg We welcome correspondence in Welsh Bwrdd Iechyd Addysgu Powys yw enw gweithredd Bwrdd Iechyd Lleol Powys Teaching Health Board is the operational name of Addysgu Powys Powys Teaching Local Health Board 5. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Petitions Committee, 02/03/2021 09

------------------------ Public Document Pack ------------------------ Agenda - Petitions Committee Meeting Venue: For further information contact: Video Conferencing Via Zoom Graeme Francis - Committee Clerk Meeting date: 2 March 2021 Kayleigh Imperato – Deputy Clerk Meeting time: 09.00 0300 200 6373 [email protected] ------ In accordance with Standing Order 34.19, the Chair has determined that the public are excluded from the Committee's meeting in order to protect public health. This meeting will be broadcast live on www.senedd.tv 1 Introduction, apologies, substitutions and declarations of interest (Pages 1 - 43) 2 New Covid 19 petitions 2.1 P-05-1118 Allow parents of under 1 year old to form a support bubble in new Tier 4 Covid restrictions (Pages 44 - 47) 2.2 P-05-1123 Raise the priority of non-NHS public facing key workers in the roll out of the Covid-19 vaccine (Pages 48 - 51) 2.3 P-05-1124 Allow two individuals from two different households to meet for exercise in alert level 4 (Pages 52 - 53) 2.4 P-05-1127 Reduce the fee limit for all Welsh universities due to COVID-19 requirement of distanced learning (Pages 54 - 57) 2.5 P-05-1128 Cancel externally set ‘assessments’ in 2021 for AS and A levels and only use teacher assessed grades (Pages 58 - 62) 2.6 P-05-1135 Targeted funding for residential outdoor education centres, now unable to operate for 12 months (Pages 63 - 70) 2.7 P-05-1136 Allow Welsh residents to travel for fishing the same as our counterparts in England (Pages 71 - 75) 2.8 P-05-1139 Extend stamp duty relief -

Bundle Quality, Safety and Experience Committee 17 December 2019

Bundle Quality, Safety and Experience Committee 17 December 2019 Agenda attachments 00 - Agenda Dec 2019 - v3.docx 1 STANDING ITEMS 1.1 Welcome and Introductions Susan Elsmore 1.2 Apologies for Absence Susan Elsmore 1.3 Declarations of Interest Susan Elsmore 1.4 Minutes of the Committee Meeting held on 17 September 2019 and 15 October 2019 Susan Elsmore 1.4 - QSE Public Mins 17.09.19 NF Final.docx 1.4.1 - QSE Mins 15.10.19 v2 - AF.NF Final.docx 1.5 Action Log - 17 September 2019 and 15 October 2019 Susan Elsmore 1.5 Action Log Sep 2019.docx 1.6 Chair's Action taken since last meeting Susan Elsmore 1.7 Clinical Board Assurance Report: Clinical Diagnostics and Therapeutics Clinical Board Aled Roberts 1.7 - CD&T Board Assurance Report.pdf 2 PATIENT STORY 3 ITEMS FOR REVIEW AND ASSURANCE 3.1 Healthcare Standards Self-Assessment Plan and Progress Update Carol Evans 3.1 -Health and Care standards Dec 2019_v 4 FINAL.docx 3.1.1 - Appendix 1 - ISN 2019 003 - Resuscitation trolley checks.pdf 3.1.2 - Appendix 2 H&CS_Dec_2019 v3 FINAL.docx 3.2 Point of Care Testing Stuart Walker 3.2 - QSE POCT SBAR 171219 (002) Final.docx 3.3 Update on Stroke Rehabilitation and Model Workforce Verbal - Fiona Jenkins 3.4 Local Clinical Audit Plan Update Stuart Walker 3.4 - Clinical Audit Plan Update -18.12.18.docx 3.4.1 - Local Clinial Audit appendix 1.xlsx 3.5 Cancer Peer Review Stuart Walker 3.6 - Peer Review report for QSE Dec 19.docx 3.6 Internal Inspections Ruth Walker 3.6 - Internal Inspections QSE.docx 3.7 Patient Notification Exercises in Cardiff and Vale -

Integrated Medium Term Plan Summary 2017-18

Welsh Ambulance Services NHS Trust Integrated Medium Term Plan Summary 2017-2018 Published: MARCH 2017 www.ambulance.wales.nhs.uk www.facebook.com/welshambulanceservice @WelshAmbulance 0 1- INTRODUCTION Welcome to the summary document of our Integrated Medium Term Plan (IMTP). We are conscious that our IMTP is a lengthy, technical document that many may not have the time to read. This summary is our way of trying to make such an important document more reader friendly. The IMTP document is a requirement of Welsh Government for all Health Boards and Trusts in NHS Wales and it sets out our direction for the next three years stating our priorities, challenges and main risks. Throughout the main plan we commit ourselves to 48 actions which can be viewed in more detail in the main IMTP. We believe our IMTP is vital for us in WAST, regardless of it being a necessity for Welsh Government, to ensure there is a clear plan in place for the organisation. In a message from the Chair and Chief Executive they have stated how reshaping an ambulance service is a long term process and therefore a need to focus on our services and how we deliver them especially as the type of patients we are seeing are changing within our ageing population. This can only be achievable with support from our partners and ensuring our teams have the right skills. We hope you find this summary a useful insight into the Trust and the work we are continuing to do to improve the quality of care we deliver to our patients. -

Paper 1: Cwm Taf Morgannwg University Health Board , Item 2

Pwyllgor Iechyd, Gofal Cymdeithasol a Chwaraeon Health, Social Care and Sport Committee HSCS(5)-07-20 Papur 1 / Paper 1 National Assembly for Wales Health, Social Care and Sport Committee ROYAL GLAMORGAN HOSPITAL EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT SERVICES Contact: Mark Dickinson, Programme Director Cwm Taf Morgannwg University Health Board Date: Written Evidence prepared 19 February 2020 Oral evidence session planned for 27 February 2020 Attending Professor Marcus Longley, Chair to give Dr Sharon Hopkins, Interim Chief Executive evidence: Dr Nick Lyons, Executive Medical Director Cwm Taf Morgannwg University Health Board Introduction 1. Cwm Taf Morgannwg University Health Board (CTM UHB) welcomes the opportunity to discuss the current situation at the Emergency Department the Royal Glamorgan Hospital and the consequential development of the future model of care. 2. This briefing paper provides members of the Committee with information about the background, rationale and progress of a project instigated by the CTM UHB to consider the outstanding recommendations of the South Wales Programme (SWP) and how they should be appropriately considered and progressed in the current context. Background 3. The SWP within NHS Wales was set up in 2012 to look at the future of four consultant-led hospital services, specifically, maternity services, neonatal care, inpatient paediatric services and emergency medicine. These services were selected for consideration due to their fragility, in terms of their ability to deliver safe and sustainable models of care, as then configured. 4. The SWP was a partnership of the five health boards serving people living in South Wales and South Powys, working with the Welsh Ambulance Services NHS Trust (WAST). -

Right Here Learning Disability Wales Annual Conference 2019 6 November 2019 • Newport How to Keep in Contact

Right here Learning Disability Wales Annual Conference 2019 6 November 2019 • Newport How to keep in contact Learning Disability Wales 41 Lambourne Crescent Cardiff Business Park Llanishen Cardiff CF14 5GG 029 2068 1160 [email protected] www.ldw.org.uk @ldwales learningdisabilitywales #righthereldw 2 Right here I would like to wish you the warmest of welcomes to our Annual Conference for 2019. I know I speak for many of the team at Learning Disability Wales when I say that conference time is our favourite time of the year. Our inclusive conferences and events are certainly something we are very proud of. Our conference offers the opportunity for people with a learning disability to come together with others to understand what makes a difference in people’s lives and ensures that people with a learning disability can access their rights and live independently now and in the future. This year our conference takes place over 2 locations and will showcase the very best practice in Wales. We will hear from speakers, take part in workshops, and learn new things. We hope you will share your knowledge and let us know how we can work to support a better Wales for people with a learning disability. Zoe Richards CEO, Learning Disability Wales ‘Right here’ is part of Learning Disability Wales’ Valued Lives project 3 www.ldw.org.uk Contents What’s happening in the morning .......................................................................... 5 What’s happening in the afternoon ....................................................................... 6 Workshops ........................................................................................................................ 8 Delegates ...................................................................................................................... 11 Exhibitors ......................................................................................................................... 18 Quiet room Available all day in the Wye Suite at the end of the corridor in reception. -

Operational Plan 2019-2020 Cwm Taf Morgannwg Community Health Council

Operational Plan 2019-2020 Cwm Taf Morgannwg Community Health Council Operational Plan 2019-2020 Cwm Taf Morgannwg Community Health Council 1 Operational Plan 2019-2020 Cwm Taf Morgannwg Community Health Council Contents Chair’s Introduction .................................................... 3 About our Community Health Council ......................... 4 Our Strategic Framework 2017 - 2020 ........................ 4 Our equality objectives ............................................... 5 Resources – Our people .............................................. 6 Making a difference through our activities .................. 8 Deciding what we do and how to do it .......................... 9 How we work with others and why ............................ 11 Our local themes and priorities in 2019/2020 .......... 12 National Themes ....................................................... 15 Complaints advocacy ................................................ 16 Responding to change proposals .............................. 17 Developing ourselves to deliver effectively ............... 22 How to get involved ................................................... 23 How to contact us ..................................................... 25 Appendix 1 ................................................................ 26 Full Council Membership 2019 - 2020 ........................... 26 Appendix 2 ................................................................ 27 CHC Representation on NHS Committees and Groups ..... 27 Appendix 3 ............................................................... -

Local Review: Welsh Ambulance Service Trust

WELSH AMBULANCE SERVICE TRUST LOCAL REVIEW Local Review: Welsh Ambulance Service Trust Assessment of Patient Management Arrangements within Emergency Medical Service Clinical Contact Centres 1 WELSH AMBULANCE SERVICE TRUST LOCAL REVIEW This publication and other HIW information can be provided in alternative formats or languages on request. There will be a short delay as alternative languages and formats are produced when requested to meet individual needs. Please contact us for assistance Copies of all reports, when published, will be available on our website or by contacting us: In writing: Communications Manager Healthcare Inspectorate Wales Welsh Government Rhydycar Business Park Merthyr Tydfil CF48 1UZ Or via Phone: 0300 062 8163 Email: [email protected] Website: www.hiw.org.uk Mae’r ddogfen yma hefyd ar gael yn Gymraeg. This document is also available in Welsh. 2 WELSH AMBULANCE SERVICE TRUST LOCAL REVIEW Contents 5 Foreword 6 Summary 7 Background 8 What we did 9 What we found 9 Patient Management Arrangements 15 Workforce 23 Governance Arrangements which support Quality and Patient Safety 25 Conclusion 26 What next? 27 Appendix A – Management Response Action Plan 3 WELSH AMBULANCE SERVICE TRUST LOCAL REVIEW Healthcare Inspectorate Wales (HIW) is the independent inspectorate and regulator of healthcare in Wales Our purpose Through our work we aim to: To check that people in Wales receive good quality healthcare. Provide assurance: Provide an independent view on the quality Our values of care. We place patients at the heart of what we do. Promote improvement: Encourage improvement through reporting We are: and sharing of good practice. • Independent • Objective Influence policy and standards: • Caring Use what we find to influence policy, • Collaborative standards and practice.