Anal Fissure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1311 Diploma in Medical Record Science Second

[LD 0212] AUGUST 2013 Sub. Code: 1311 DIPLOMA IN MEDICAL RECORD SCIENCE SECOND YEAR PAPER II – INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF DISEASES (ICD-10) & SURGICAL PROCEDURES (ICM-9CM) Q.P. Code : 841311 Time : Three Hours Maximum : 100 marks Answer ALL questions I Write appropriate codes using ICD -10 (30 x 1 = 30) 1. Therapeutic introduction of hand tendon. 2. Excision of major partial thickness of eyelid excision. 3. Interphalangeal arthrodesis of Toe. 4. Division of percutaneous spinal cord nerve tracts. 5. Transfusion of allograft bone aetriosus. 6. Rastelli operation of truncus arteriosus. 7. Pyoloric sphincter dilatation. 8. Stapling of radius epiphyseal plate. 9. Suture of hands fascia. 10. Suture of hand fascia. 11. Repair of anterior wall (abdomen) hernia. 12. Foreign body removal without incision in t o the brain. 13. Repair of Tetrology of fallot. 14. Frontal Sinusectomy. 15. Urethral sling suspension. 16. Bone shaft transfer. 17. Coil of aneuryum repair. 18. Sling suspension. 19. Radio isotope scanning, pituitary gland. 20. Spinal shunt removal. 21. Acute lung edema. Due to external agent. 22. Proximal end tibial closed fracture was riding a two wheeler-slip & fell down. 23. Thrombosed internal hemorrhoids. 24. Secondary hypertension due to renal disorder. 25. Old myocardial infarction. 26. Fall from high place, injured elbow. 27. Chronic venous (peripheral) insufficiency. 28. Acute myeloid leukemia. 29. Post-operative intestine obstruction. 30. Abnormal pregnancy. II Writes appropriate codes using ICS-9CM (20 x 2 = 40) 1. Pregnant women suffering from acute salphingo oophoritis. 2. Accidental intake of ferrous salt. 3. Sprain of lumbar spine as stuck by another person. 4. -

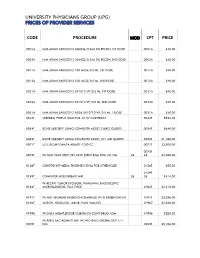

Code Procedure Cpt Price University Physicians Group

UNIVERSITY PHYSICIANS GROUP (UPG) PRICES OF PROVIDER SERVICES CODE PROCEDURE MOD CPT PRICE 0001A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 30MCG/0.3ML DIL RECON 1ST DOSE 0001A $40.00 0002A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 30MCG/0.3ML DIL RECON 2ND DOSE 0002A $40.00 0011A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 100 MCG/0.5 ML 1ST DOSE 0011A $40.00 0012A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 100 MCG/0.5 ML 2ND DOSE 0012A $40.00 0021A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 5X1010 VP/0.5 ML 1ST DOSE 0021A $40.00 0022A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 5X1010 VP/0.5 ML 2ND DOSE 0022A $40.00 0031A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 AD26 5X10^10 VP/0.5 ML 1 DOSE 0031A $40.00 0042T CEREBRAL PERFUS ANALYSIS, CT W/CONTRAST 0042T $954.00 0054T BONE SURGERY USING COMPUTER ASSIST, FLURO GUIDED 0054T $640.00 0055T BONE SURGERY USING COMPUTER ASSIST, CT/ MRI GUIDED 0055T $1,188.00 0071T U/S LEIOMYOMATA ABLATE <200 CC 0071T $2,500.00 0075T 0075T PR TCAT PLMT XTRC VRT CRTD STENT RS&I PRQ 1ST VSL 26 26 $2,208.00 0126T CAROTID INT-MEDIA THICKNESS EVAL FOR ATHERSCLER 0126T $55.00 0159T 0159T COMPUTER AIDED BREAST MRI 26 26 $314.00 PR RECTAL TUMOR EXCISION, TRANSANAL ENDOSCOPIC 0184T MICROSURGICAL, FULL THICK 0184T $2,315.00 0191T PR ANT SEGMENT INSERTION DRAINAGE W/O RESERVOIR INT 0191T $2,396.00 01967 ANESTH, NEURAXIAL LABOR, PLAN VAG DEL 01967 $2,500.00 01996 PR DAILY MGMT,EPIDUR/SUBARACH CONT DRUG ADM 01996 $285.00 PR PERQ SAC AGMNTJ UNI W/WO BALO/MCHNL DEV 1/> 0200T NDL 0200T $5,106.00 PR PERQ SAC AGMNTJ BI W/WO BALO/MCHNL DEV 2/> 0201T NDLS 0201T $9,446.00 PR INJECT PLATELET RICH PLASMA W/IMG 0232T HARVEST/PREPARATOIN 0232T $1,509.00 0234T PR TRANSLUMINAL PERIPHERAL ATHERECTOMY, RENAL -

Anal Fissure

Anal Fissure What is an anal fissure? An anal fissure is a small tear in the skin of the anus. The anus is the opening of the rectum where bowel movements (BMs) leave the body. Anal fissures are a fairly common problem. What is the cause? A tear may happen when you have: • Hard, dry bowel movements • Constipation • Hemorrhoids • Anal surgery • Inflammation of the rectum caused by intestinal problems such as Crohn's disease What are the symptoms? Symptoms may include: • Pain during or after bowel movements • Cramping of the muscle at the opening of the anus caused by irritation of the tear during a bowel movement • Bright red blood when you have a bowel movement (you may see the blood on the BM, in the toilet water, or on toilet tissue you have used) How is it diagnosed? Your healthcare provider will ask about your symptoms and examine you. You may have a procedure called an anoscopy to confirm the diagnosis. For this procedure your provider uses a small tool with a light called an anoscope to examine the anus and lower part of the rectum. Your healthcare provider may recommend other tests or procedures, such as a sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy, to learn more about the cause of the fissure or the bleeding. How is it treated? Most fissures will heal with the following at-home treatments: • Your healthcare provider may recommend a stool softener, such as Haley's M-O, psyllium, Metamucil or Citrucel, or mineral oil. • It may help to drink lots of water and add more fiber to your diet. -

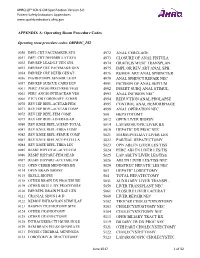

PSI Appendix a Version 6.0 Patient Safety Indicators Appendices

AHRQ QI™ ICD-9-CM Specification Version 6.0 Patient Safety Indicators Appendices www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov APPENDIX A: Operating Room Procedure Codes Operating room procedure codes: ORPROC_PSI 0050 IMPL CRT PACEMAKER SYS 4972 ANAL CERCLAGE 0051 IMPL CRT DEFIBRILLAT SYS 4973 CLOSURE OF ANAL FISTULA 0052 IMP/REP LEAD LF VEN SYS 4974 GRACILIS MUSC TRANSPLAN 0053 IMP/REP CRT PACEMAKR GEN 4975 IMPL OR REV ART ANAL SPH 0054 IMP/REP CRT DEFIB GENAT 4976 REMOV ART ANAL SPHINCTER 0056 INS/REP IMPL SENSOR LEAD 4979 ANAL SPHINCT REPAIR NEC 0057 IMP/REP SUBCUE CARD DEV 4991 INCISION OF ANAL SEPTUM 0061 PERC ANGIO PRECEREB VESS 4992 INSERT SUBQ ANAL STIMUL 0062 PERC ANGIO INTRACRAN VES 4993 ANAL INCISION NEC 0066 PTCA OR CORONARY ATHER 4994 REDUCTION ANAL PROLAPSE 0070 REV HIP REPL-ACETAB/FEM 4995 CONTROL ANAL HEMORRHAGE 0071 REV HIP REPL-ACETAB COMP 4999 ANAL OPERATION NEC 0072 REV HIP REPL-FEM COMP 500 HEPATOTOMY 0073 REV HIP REPL-LINER/HEAD 5012 OPEN LIVER BIOPSY 0080 REV KNEE REPLACEMT-TOTAL 5014 LAPAROSCOPIC LIVER BX 0081 REV KNEE REPL-TIBIA COMP 5019 HEPATIC DX PROC NEC 0082 REV KNEE REPL-FEMUR COMP 5021 MARSUPIALIZAT LIVER LES 0083 REV KNEE REPLACE-PATELLA 5022 PARTIAL HEPATECTOMY 0084 REV KNEE REPL-TIBIA LIN 5023 OPN ABLTN LIVER LES/TISS 0085 RESRF HIPTOTAL-ACET/FEM 5024 PERC ABLTN LIVER LES/TIS 0086 RESRF HIPPART-FEM HEAD 5025 LAP ABLTN LIVER LES/TISS 0087 RESRF HIPPART-ACETABLUM 5026 ABLTN LIVER LES/TISS NEC 0112 OPEN CEREB MENINGES BX 5029 DESTRUC HEPATIC LES NEC 0114 OPEN BRAIN BIOPSY 503 HEPATIC LOBECTOMY 0115 SKULL BIOPSY 504 TOTAL -

Curriculum Outline General Surgery

CURRICULUM OUTLINE FOR GENERAL SURGERY 2018–2019 Surgical Council on Resident Education 1617 John F. Kennedy Boulevard Suite 860 Philadelphia, PA 19103 1-877-825-9106 [email protected] www.surgicalcore.org SCORE Curriculum Outline for General Surgery The SCORE® Curriculum Outline for General Surgery is a list of topics to be covered in a five- year general surgery residency program. The outline is updated annually to remain contempo- rary and reflect feedback from SCORE member organizations and specialty surgical societies. Topics are listed for all six competencies of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME): patient care; medical knowledge; professionalism; interpersonal and communication skills; practice-based learning and improvement; and systems-based practice. The patient care topics cover 27 organ system- based categories, with each category separated into Diseases/Conditions and Operations/ Procedures. Topics within these two areas are then designated as Core or Advanced. Changes from the previous edition are indi- cated in the Excel version of this outline, avail- able at www.surgicalcore.org. Note that topics listed in this booklet may not directly match those currently on the SCORE Portal — this outline is forward-looking, reflecting the latest updates. The Surgical Council on Resident Education (SCORE) is a nonprofit consortium formed in 2006 by the principal organizations involved in U.S. surgical education. SCORE’s mission is to improve the education of general surgery residents through the development of a national curriculum for general surgery residency training. The members of SCORE are: American Board of Surgery American College of Surgeons American Surgical Association Association of Program Directors in Surgery Association for Surgical Education Review Committee for Surgery of the ACGME Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons PATIENT CARE CONTENTS Page BY CATEGORY ............................................ -

Icd-9-Cm (2010)

ICD-9-CM (2010) PROCEDURE CODE LONG DESCRIPTION SHORT DESCRIPTION 0001 Therapeutic ultrasound of vessels of head and neck Ther ult head & neck ves 0002 Therapeutic ultrasound of heart Ther ultrasound of heart 0003 Therapeutic ultrasound of peripheral vascular vessels Ther ult peripheral ves 0009 Other therapeutic ultrasound Other therapeutic ultsnd 0010 Implantation of chemotherapeutic agent Implant chemothera agent 0011 Infusion of drotrecogin alfa (activated) Infus drotrecogin alfa 0012 Administration of inhaled nitric oxide Adm inhal nitric oxide 0013 Injection or infusion of nesiritide Inject/infus nesiritide 0014 Injection or infusion of oxazolidinone class of antibiotics Injection oxazolidinone 0015 High-dose infusion interleukin-2 [IL-2] High-dose infusion IL-2 0016 Pressurized treatment of venous bypass graft [conduit] with pharmaceutical substance Pressurized treat graft 0017 Infusion of vasopressor agent Infusion of vasopressor 0018 Infusion of immunosuppressive antibody therapy Infus immunosup antibody 0019 Disruption of blood brain barrier via infusion [BBBD] BBBD via infusion 0021 Intravascular imaging of extracranial cerebral vessels IVUS extracran cereb ves 0022 Intravascular imaging of intrathoracic vessels IVUS intrathoracic ves 0023 Intravascular imaging of peripheral vessels IVUS peripheral vessels 0024 Intravascular imaging of coronary vessels IVUS coronary vessels 0025 Intravascular imaging of renal vessels IVUS renal vessels 0028 Intravascular imaging, other specified vessel(s) Intravascul imaging NEC 0029 Intravascular -

Pediatric and Adolescent Gastrointestinal Motility & Pain

Defecation Disorders After Surgery for Hirschsprung's Disease Pediatric and Adolescent Gastrointestinal Motility & Pain Program Department of Pediatrics, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, Louisiana Over 1000 new cases of Hirschsprung’s disease are diagnosed in the USA every year. More than half the children treated appropriately with surgery for Hirschsprung’s disease suffer from chronic problems with constipation, incontinence, and/or abdominal pain. Even as adults, over half will experience occasional episodes of incontinence, and 10% will endure constipation unresponsive to medical management. In the six decades since Ovar Swenson recognized that the distal bowel segment lacking ganglion cells was the diseased portion and created the first successful surgical technique, surgeons have been frustrated with the imperfect response to a surgery which eliminates the disease. Parents have been frustrated and children shamed by the inability to gain control over their bowel movements. Over the past 10 years the pediatric motility community has discovered reasons and solutions for chronic post-operative problems. It is now clear that the child is not lazy or uncooperative, but has recognizable and treatable causes for the symptoms. Constipation There are three mechanisms for constipation: functional constipation (also called functional fecal retention), neuropathy proximal to the aganglionic segment, and hypertensive anal sphincter. It is not easy to distinguish among these conditions when they follow Hirschsprung’s disease surgery. Only colon and anorectal manometry clarify the diagnosis and treatment. Functional constipation Functional constipation is the most common condition referred to pediatric gastroenterology clinics. It arises when an infant or toddler has a painful bowel movement. -

Approved Surgical Procedures

UNION MEDICAL BENEFITS SOCIETY LTD APPROVED SURGICAL PROCEDURES The following list of surgical procedures should be read in conjunction with your policy document. If you are intending to have one of the listed procedures, please call our surgical team on 0800 600 666 so we can guide you through the prior approval process. If a surgical procedure is not listed below, it will not be covered unless UniMed decides, in its sole discretion, to offer cover. CARDIAC GENERAL • Pericardiotomy Breast • Pericardiocentesis • Breast Cyst Aspiration or Needle Biopsy • Drainage of Pericaridal Effusion • Breast Biopsy • Coronary Artery Bypass (using vein or artery) • Core Biopsy of Breast • Open Repair of Atrial Septal Defect (ASD) • Excision Accessary Breast Tissue • Valvuloplasty • Mastectomy • Aortic/ Mitral Valve Replacement via Sternotomy • Sentinel Node Biopsy with/without Axillary Dissection • Pulmonary Valve Replacement via Sternotomy • Breast Microdochotomy • Tricuspid Valve Replacement via Sternotomy • Balloon Valvuloplasty – Mitral/ Aortic Reconstruction Post Mastectomy • Pacemaker Surgery – Initial Implantation (Excluding the Cost • Breast/ Nipple Reconstruction of the Pacemaker) • Nipple Areolar Tattoo • Removal of Sternal Wire • Maze Arrhythmia Surgery Gastrointestinal • Removal & Rewiring of Sternal Wire • Anal Sphincterotomy • Maze Arrhythmia Surgery (Standalone procedure) • Simple Repair of Anal Fistula – Special approval only • Maze Procedure – Thoracoscopic • Anal Fistula Repair with Mucosal Advancement Flap • Bentall’s Procedure (includes -

SCORE Curriculum Outline for General Surgery

SCORE Curriculum Outline 2015-2016 - Patient Care Module Not Yet on Portal (x) Category # Patient Care Category Type Level Patient Care Topic 1 Abdomen - General Disease/Condition Core Abdominal Pain - Acute 1 Abdomen - General Disease/Condition Core Intra-abdominal Abscess 1 Abdomen - General Disease/Condition Core Rectus Sheath Hematoma 1 Abdomen - General Disease/Condition Advanced Abdominal Pain - Chronic 1 Abdomen - General Disease/Condition Advanced Ascites - Chylous 1 Abdomen - General Disease/Condition Advanced Bacterial Peritonitis - Spontaneous 1 Abdomen - General Disease/Condition Advanced Desmoids/Fibromatoses 1 Abdomen - General Disease/Condition Advanced Mesenteric Cyst 1 Abdomen - General Disease/Condition Advanced Peritoneal Neoplasms - Carcinomatosis 1 Abdomen - General Disease/Condition Advanced Peritoneal Neoplasms - Pseudomyxoma Peritonei 1 Abdomen - General Operation/Procedure Core Diagnostic Laparoscopy 1 Abdomen - General Operation/Procedure Core Intra-abdominal Abscess - Drainage 1 Abdomen - General Operation/Procedure Core Peritoneal Dialysis Catheter Insertion 1 Abdomen - General Operation/Procedure Core Peritoneal Lesion - Biopsy 1 Abdomen - General Operation/Procedure Advanced Pseudomyxoma - Operation 2 Abdomen - Hernia Disease/Condition Core Inguinal and Femoral Hernia 2 Abdomen - Hernia Disease/Condition Core Miscellaneous Hernias 2 Abdomen - Hernia Disease/Condition Core Prosthetic Mesh Infections - Management 2 Abdomen - Hernia Disease/Condition Core Umbilical and Epigastric Hernias 2 Abdomen - Hernia Disease/Condition -

Anal Fissures David B

CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Anal Fissures David B. Stewart, Sr., M.D. • Wolfgang Gaertner, M.D. • Sean Glasgow, M.D. John Migaly, M.D. • Daniel Feingold, M.D. • Scott R. Steele, M.D. Prepared on behalf of the Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons he American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons anal fissures is anal pain, which is often provoked by def- is dedicated to ensuring high-quality patient care ecation and may last for several hours following defecation. Tby advancing the science, prevention, and manage- Anorectal bleeding may also be associated with fissures, ment of disorders and diseases of the colon, rectum, and and, when this symptom is present, it can contribute to a anus. The Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee is com- misdiagnosis of symptomatic hemorrhoids. In up to 90% of posed of society members who are chosen because they cases, the anal fissure is located within the posterior midline have demonstrated expertise in the specialty of colon and of the anal canal. Fissures are located in the anterior midline rectal surgery. This committee was created to lead interna- in as many as 25% of female patients and in as many as 8% tional efforts in defining quality care for conditions related of male subjects. In 3% of patients, fissures can be located to the colon, rectum, and anus. This is accompanied by at posterior and anterior positions simultaneously. Fissures developing clinical practice guidelines based on the best located at lateral locations within the anal canal, and multi- available evidence. -

Lateral Internal Sphincterotomy Versus Anal Dilatation in Chronic Anal Fissure - an Observational Study

International Journal of Health Sciences and Research www.ijhsr.org ISSN: 2249-9571 Original Research Article Lateral Internal Sphincterotomy versus Anal Dilatation in Chronic Anal Fissure - An Observational Study Rakesh Kumar Pandit1, Vinay Kumar Jha2 1Associate Professor and Head, Department of Surgery, Janaki Medical College and Teaching Hospital, Janakpur, Nepal 2Assistant Professor, Department of Surgery, Janaki Medical College and Teaching Hospital, Janakpur, Nepal Corresponding Author: Rakesh Kumar Pandit ABSTRACT Background and Objectives: Both anal dilatation (AD) and lateral internal sphincterotomy (LIS) are practiced in our hospital for treatment of chronic anal fissure (CAF). The objective of the study was to compare the two procedures especially regarding pain relief, ulcer healing, incontinence and recurrence. Material and Methods: This is an observational study and included 50 patients of AD (Group A) and 44 patients of LIS (Group B). The average follow-up was 3.5 ± 4.9 (range, 1-9) months. Results: By the end of 1 month pain relief was observed in 45 (90%) and 42 (95.45%) patients and ulcer healing in 47 (94%) and 43 (97.7%) patients in group A and B respectively. By the end of 3 months, minor incontinence including mucous discharge was observed in 12 (24%) and 3 (6.8%) patients in group A and B respectively and the difference was significant (p=0.046). None had major incontinence. Eight (16%) and 1 (2.27%) patients in group A and group B respectively reported with recurrence (p = 0.05) during the study period and thereafter. Conclusion: Both AD and LIS provides early pain relief and high ulcer healing rate. -

CAFM Consensus Statement for Procedural Training in Family Medicine Residency

CAFM Consensus Statement for Procedural Training in Family Medicine Residency Preamble: Procedural skills are expected of all family medicine residency graduates. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Review Committee for Family Medicine (RC-FM) in its 2014 revision of the Family Medicine requirements FAQ (frequently asked questions), stated that national organizations of family medicine should develop training guidelines for procedural training for the specialty.1 A task force was convened with the support of the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors (AFMRD) that included experienced faculty and program directors from across the country and CAFM member organizations. This consensus report represents the collective wisdom of experienced educators building upon a foundation of established literature and existing standards in determining best practices for informing what defines procedural competency. The task force recognized that family physicians in practice may perform a wide range of procedures, and that there is significant variance among physicians-in-training for procedural skills. This variance may lead to confusion among employers, credentialing bodies, and patients about what services a trained family physician should be able to provide. Using procedure taxonomy that the STFM Group on Hospital Medicine and Procedural Training previously defined,2,3 as well as data from the American Academy of Family Physicians membership survey regarding the scope of procedures performed in practice,4 the task force recommends a core list of procedures that family physicians should be able to perform at the completion of their residency. The task force also recommends a set of standardized criteria to be used for measuring competency in these procedures and has developed tools program directors and residency faculty may use to do so.