Aarhus Documents 01 a Beaux Arts Education for the 21St Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archi-Ne Ws 2/20 17

www.archi-europe.com archi-news 2/2017 BUILDING AFRICA EDITO If the Far East seems to be the focal point of the contemporary architectural development, the future is probably in Africa. Is this continent already in the line 17 of vision? Many European architects are currently building significant complexes: 2/20 the ARPT by Mario Cucinella, the new hospital in Tangiers by Architecture Studio or the future urban development in Oran by Massimiliano Fuksas, among other projects. But the African architectural approach also reveals real dynamics. This is the idea which seem to express the international exhibitions on African architecture during these last years, on the cultural side and architectural and archi-news archi-news city-panning approach, as well as in relation to the experimental means proposed by numerous sub-Saharan countries after their independence in the sixties, as a way to show their national identity. Not the least of contradictions, this architecture was often imported from foreign countries, sometimes from former colonial powers. The demographic explosion and the galloping city planning have contributed to this situation. The recent exhibition « African Capitals » in La Villette (Paris) proposes a new view on the constantly changing African city, whilst rethinking the evolution of the African city and more largely the modern city. As the contemporary African art is rich and varied – the Paris Louis Vuitton Foundation is presently organizing three remarkable exhibitions – the African architecture can’t be reduced to a single generalized label, because of the originality of the different nations and their socio-historical background. The challenges imply to take account and to control many parameters in relation with the urbanistic pressure and the population. -

Read the Correspondent Article

Winter 2015 SILENT KILLER DR. KAZEM BEHBEHANI ON THE FIGHT CAPITAL ASSETS AGAINST DIABETES BANKING DOYENNE BY ROYAL APPOINTMENT NEMAT SHAFIK LYNNE DAVIS ON EMINENT BRITISH PRINTERS BARNARD & WESTWOOD CULTURE CLASH BARUCH SPIEGEL RETHINKING SPECIAL NEEDS EDUCATION IN KUWAIT OUTER SPACES SALMAN ZAFAR EXTOLLS THE NEED FOR GREEN UTZON UNTOLD KUWAIT NATIONAL ASSEMBLY: THE MAKING OF A MASTERPIECE IN CONVERSATION HaIlIng from a DanIsh desIgn dynasty, Jan Utzon speaks to Charlotte Shalgosky about workIng wIth hIs father, the globally-recognIzed Jørn Utzon, on hIs desIgn of the KuwaIt NatIonal Assembly. Jan Utzon greets me warmly, even and environmental sympathies in his native Denmark he is strikingly most eloquently; a building that, tall. Looking much younger than his when it frst opened, epitomized seventy-plus years his limber frame the simplicity and the sensitivity of and sparkling eyes are remarkably Utzon’s understated brilliance as reminiscent of his father, Jørn, much as his love of the Middle East. with whom he worked so closely Even before it was completed, the throughout his life. late British architectural critic Stephen Gardiner wrote “When fnished, it Jørn Utzon died in 2008 having won will be one of the great buildings almost every architectural prize of the world”. and accolade, and having been lauded for his visionary designs. In 1968, when the competition Columbia University Professor, to design the Kuwait National Kenneth Frampton, wrote in the Assembly was being held, Jan Harvard Design Magazine “Nobody was just starting out on his own can study the future of architecture career in architecture in Denmark; without Jørn Utzon”. -

Enjoying the Outdoors Since 1947 Vestre of Norway Presents Street Furniture with Emphasis on Quality, Innovation and Function

VESTRE AT CLERKENWELL DESIGN WEEK 2014 Enjoying the outdoors since 1947 Vestre of Norway presents street furniture with emphasis on quality, innovation and function. The design is rooted in the principle of the Scandinavian aesthetic: products that are accessible and available to everyone. DATE: 20-22 MAY 2014 POP-UP EXHIBITION LOCATION: ST JAMES’ CHURCH GARDEN, CLERKENWELL CLOSE, LONDON EC1R 0EA Vestre invites you to visit our exhibition at the historic Clerkenwell site, which is the perfect venue to exhibit Vestre’s collection of street furniture and to enjoy the outdoors. We are delighted to announce that we will be serving genuine Scandinavian outdoor lunches. Vestre’s furniture is intended to bring something unique to, and cope with use in, the urban streetscape. It has to be usable summer and winter, year after year. This challenges the designer to create furniture that is not only timelessly elegant, but sufficiently strong and durable too. “The quality requirements for our furniture are tough and uncompromising, but not at the expense of innovative, playful design,” says CEO Jan Christian Vestre. He stresses how important it is to try out new concepts and a selection of this year’s news is part of the pop-up exhibition at Clerkenwell Design Week 2014: • Vestre BUZZ is a retro futuristic-inspired bench and table in circular form. • Vestre MOVE is a bench inspired by motion that is an invitation to take a welcome breather. • Vestre BLOC sun bench adds something more to a seating area: a place to Contacts: sit and be while soaking up some sun. -

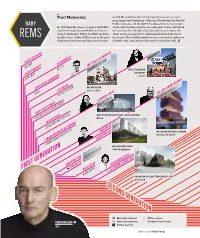

First Generation Second Generation

by Paul Makovsky world. Not only has the firm designed some of our era’s most important buildings—Maison à Bordeaux, the Seattle BABY Public Library, and the CCTV headquarters, to name just In 1975 Rem Koolhaas, together with Elia a few—but its famous hothouse atmosphere has cultivated and Zoe Zenghelis and Madelon VriesenVriesen-- the talents of hundreds of gifted architects. Look at the dorp, founded the Office for Metropolitan chart on these pages: it is a distinguished architectural REMS Architecture. Today OMA is one of the most fraternity. These OMA grads have now created an influence influential architectural practices in the all their own, and they are the ones to watch in 2011. P ZAHA HADID RIENTS DIJKSTRA EDZO BINDELS MAXWAN MATTHIAS SAUERBRUCH WEST 8 SAUERBRUCH HUTTON EVELYN GRACE ACADEMY CHRISTIAN RAPP London RAPP + RAPP CHRISTOPHE CORNUBERT M9 MUSEUM LUC REUSE Venice, Italy WILLEM JAN NEUTELINGS PUSH EVR ARCHITECTEN NEUTELINGS RIEDIJK LAURINDA SPEAR ARQUITECTONICA KEES CHRISTIAANSE SOUTH DADE CULTURAL ARTS CENTER KGAP ARCHITECTS AND PLANNERS Miami YUSHI UEHARA ZERODEGREE ARCHITECTURE MVRDV WINY MAAS MUSEUM AAN DE STROOM Antwerp, Belgium RUURD ROORDA KLAAS KINGMA JACOB VAN RIJS KINGMA ROORDA ARCHITECTEN BALANCING BARN Suffolk, England FOA WW ARCHITECTURE SARAH WHITING FARSHID MOUSSAVI RON WITTE FIRST GENERATION MIKE GUYER ALEJANDRO ZAERA POLO GIGON GUYER MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART Cleveland SECOND GENERATION Married/partnered Office closed REM KOOLHAAS P Divorced/separated P Pritzker Prize laureate OMA Former partner Illustration by Nikki Chung REM_Baby REMS_01_11_rev.indd 1 12/16/10 7:27:54 AM BABY REMS by Paul Makovsky In 1975 Rem Koolhaas, together with Elia and Zoe Zenghelis and Madelon Vriesen- dorp, founded the Office for Metropolitan Architecture. -

Jørn Utzon's Synthesis of Chinese and Japanese Architecture in the Design for Bagsværd Church

arq (2019), Page 1 of 22 © Cambridge University Press 2019 doi: 10.1017/S1359135518000696 history This article explores Utzon’s engagement with the cultures of Japan and China, demonstrating how he took inspiration from both calligraphy and monastery design. Jørn Utzon’s synthesis of Chinese and Japanese architecture in the design for Bagsværd Church Chen-Yu Chiu, Philip Goad, Peter Myers, Nur Yıldız Kılınçer Introduction article attempts to address the detailed process of In his essay of 1983, ‘Towards a Critical Regionalism’, Utzon’s cross-cultural practices for his design of the Kenneth Frampton referred to the Bagsværd Church Bagsværd Church in order to reveal how Utzon as a primary exemplar, briefly citing the architect’s interpreted specific ideas, ideals, and artefacts from representation of ‘the Chinese pagoda roof’ in this East Asian building culture. project, to emphasise the importance of cross- To elucidate the above unsolved issues and examine cultural inspiration in the creation of ‘critical the precise role of Chinese and Japanese architecture regionalism’.1 Peter Myers followed Frampton in his in Utzon’s design of Bagsværd Church, the authors 1993 ‘Une histoire inachevée’, arguing for the have consulted both the Utzon Archives and the family significant role that Chinese architecture played as a collection of material from his architectural career, source for Utzon’s Bagsværd Church design and while conducting interviews with Utzon’s former further variations on the theme of Chinese and assistants and his son Jan Utzon. These new primary Japanese exemplars on Utzon’s work follows. sources have allowed the authors to review Utzon’s Françoise Fromonot established the importance of design process critically and analyse the architect’s the 1925 edition of the Yingzao-fashi (State Building perception and representation of various ideas, Standard, first published in1103 ad) and Johannes ideals, and artefacts of Chinese and Japanese building Prip-Møller’s 1937 Chinese Buddhist Monasteries for culture. -

Dwelling, Landscape, Place and Making

DWELLING, LANDSCAPE, PLACE AND MAKING Jørn Utzon Anthology Lars Botin, Adrian Carter and Roger Tyrrell Copyright © 2013 by Adrian Carter, Lars Botion and Roger Tyrrell / Jørn Utzon Research Network / Utzon Research Center, Aalborg University Title: Dwelling, Landscape, Place and Making Print: Aalborg University Press Graphics and Layout: Line Nørskov Eriksen ISBN: xxx-xx-xxxx-xxx-x 1st Edition, Printed in Denmark 2013 Published with the kind support of Department of Architectural Design and Mediatechnology, Aalborg University Portsmouth School of Architecture, University of Portsmouth FORMTEXT FORMTEXT FORMTEXT CONTENTS xx Introduction Part 1 Foundation xx The Utzon Paradigm – Tyrrell, R. and Carter, A. xx Jørn Utzon: Influences and Reinterpretation – Carter, A. xx Thrills, Wiews and Shelter at Majorca – Roberts, J. xx Architecture and Camping – Taylor, P. and Hinds, M. Part 2 Influence xx Jan Utzon’s Symposium Presentation xx Rick Leplastrier’s Symposium Presentation Part 3 Reflection xx Making the World: Space, Place and Time in Architecture – Pallasmaa, J. xx Landscape and Dwelling – Botin, L. xx The Nature of Dwelling – Tyrrell, R. INTRODUCTION Background and acknowledgments This anthology is based on the Proceedings of the Third International Utzon Symposium held on 1st April 2012 in the Dar el Bacha palace, Marrakech, Morocco. The Symposium was a further development of the previous two Symposia held by the Utzon Research Center in Aalborg, Denmark and represents a collaboration between the Jørn Utzon Research Network (JURN), The Utzon Research Center and L’ Ecole Nationale d’Architecture (ENA) of Morocco. Morocco was chosen as the location for the event in recognition of the significant influence it had upon Utzon’s canon after his visit in 1949. -

D a N S K a M a J 2 0 1 5 Kopenhagen Zelena

KOPENHAGEN ZELENA PRESTOLNICA EVROPE 2014 DANSKA MAJ 2015 Dansko kraljestvo (krajše le Danska) je najstarejša in najmanjša nor- dijska drža- va, ki se nahaja v Skandinaviji v severni Evropi na polotoku vzhodno od Baltske- ga morja in jugozahodno od Severne- ga morja. Vključuje tudi številne otoke severno od Nemčije, na katero meji tudi po kopnem, in Poljske, poleg teh pa še ozemlja na Grenlandiji in Fer- skih otokih, ki so združena pod dansko krono, če- prav uživajo samou- pravo. Le četrtina teh otokov je naseljena. Danska je iz- razito položna dežela. Najvišji vrh je Ejer Bavnehoj, z 173 metri nadmorske višine. Največja reka je Gudena. zanimivosti: - Danska je mati Lego kock. Njihova zgodba se je začela leta 1932 in v več kot 60. letih so prodali čez 320 bilijonov kock, kar pomeni povprečno 56 kock na vsakega prebivalca na svetu. Zabaviščni park Legoland se nahaja v mestu Bil- lund, kjer so zgrajene različne fingure in modeli iz več kot 25 milijonov lego kock. - Danska je najpomembnejša ribiška država v EU. Ribiško ladjevje šteje prib- ližno 2700 ladij. Letni ulov znaša 2.04 miljonov ton. - Danska ima v lasti 4900 otokov. - Najbolj znan Danec je pisatelj Hans Christian Andersen. - Leta 1989 Danska postane prva Ev- ropska država, ki je legalizirala isto- spolne zakone. - Ferski otoki so nekoč pripadali Nor- veški, ki pa jih je izgubila, ko je Norveški kralj v navalu pijanosti izgubil igro pokra proti Danskemu kralju. INFO DEJSTVA O DANSKI: ORGANIZIRANI OGLEDI: Kraljevo geslo: “Božja pomoč, človeška ljubezen, KØBENHAVNS KOMMUNE danska veličina.” GUIDED TOURS OF kraljica: Margareta II. LOW ENERGY BUILDINGS Danska glavno mesto: København ga. -

The Role of Jørn Utzon's 1958 Study Trip to China in His Architectural Maturity

$UFKLWHFWXUDO Chiu, C-Y 2016 China Receives Utzon: The Role of Jørn Utzon’s 1958 Study Trip to China in His Architectural Maturity. Architectural Histories, 4(1): 12, +LVWRULHV pp. 1–25, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/ah.182 RESEARCH ARTICLE China Receives Utzon: The Role of Jørn Utzon’s 1958 Study Trip to China in His Architectural Maturity Chen-Yu Chiu Both before and after his study trip to China in 1958, Danish architect Jørn Utzon (1918–2008) consistently cited dynastic Chinese architecture as one of his essential design ideals. This article commences with a reconstruction, using archival and anecdotal evidence, of Jørn Utzon’s 1958 study trip to China with his close friend, the noted Norwegian architect Geir Grung (1926–89). The investigation seeks to explain both why, as a student, Utzon was so interested in the civilisation of China and how his carefully planned journey yielded Utzon both an intuitive grasp of ideas of Chinese architecture, and, most importantly, a continuing interest in China’s traditional systems of building construction. The answers could add to a methodological and theoretical framework for understanding Utzon’s work. Introduction This article then establishes built-form analogies Both before and after his study trip to China in 1958, the between Utzon’s 1958 study of Chinese architecture in situ Danish architect Jørn Utzon (1918–2008) consistently and his design proposals over the three decades following cited dynastic Chinese architecture as one of his essential the trip, with a view to retracing the path of Utzon’s grow- design ideas and ideals (Faber and Utzon, 1947; Utzon ing understanding of Chinese architecture during this 1962; 1970). -

Libro ZARCH 10.Indb

Bond University Research Repository Utzon: The defining light of the Third Generation Carter, Adrian; Sarvimaki, Marja Published in: ZARCH DOI: 10.26754/ojs_zarch/zarch.2018102933 Published: 01/06/2018 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Bond University research repository. Recommended citation(APA): Carter, A., & Sarvimaki, M. (2018). Utzon: The defining light of the Third Generation. ZARCH, (10), 88-99. https://doi.org/10.26754/ojs_zarch/zarch.2018102933 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. For more information, or if you believe that this document breaches copyright, please contact the Bond University research repository coordinator. Download date: 02 Aug 2019 TítuloUtzon: The defining light of the Third TítuloGeneration Utzon: La luz definidora de la Tercera Generación AUTOR ADRIAN CARTER Débora Domingo-Calabuig “A single strategy: Southeastern Massachusetts Technological Institute by Paul Rudolph” ZARCH 10 (Junio 2018): 114- 124 MARJA SARVIMÄKI ISSN: 2341-0531. http://dx.doi.org/10.26754/ojs_zarch/zarch.201792263 Recibido: 20-2-2018 Aceptado: 8-5-2018 Adrian Carter y Marja Sarvimäki, “Utzon: The defining light of the Third Generation”, ZARCH 10 (Junio 2018): 88-99 Abstract ISSN: 2341-0531. https://doi.org/10.26754/ojs_zarch/zarch.2018102933 Recibido:Paul. 6-2-2018 Aceptado: 18-5-2018 AbstractKeywords InPaul Space, Time, and Architecture, Sigfried Giedion identified Jørn Utzon as one of the proponents and leaders of what Giedion regarded as the Third Generation of modern architecture in the 20th century. -

The Pritzker Architecture Prize 2003 Presented to Jørn Utzon

THE PRITZKER ARCHITECTURE PRIZE 2003 PRESENTED TO JØRN UTZON 01 SPONSORED BY THE HYATT FOUNDATION Photo by David Messent 02 Sydney Opera House Sydney, Australia 1957-1973 Photo by David Messent 03 Sydney Opera House Sydney, Australia 1957-1973 Note to Editors: The photos included in this booklet are a sampling of the Laureates’ work, a catalogue of the images available for publication. The numbers beside the images are are for reference to a CD (in high and low resolutions), the web. The photos and drawings may only be used in the context of the Pritzker Prize announcement. For any other advertising or publicity purposes, media must contact Utzon Architects for permission. It should further be noted that the images in this booklet are all 200 line screen lithographs printed on high gloss stock. They replace the need for black & white continuous tone prints. They may be reproduced using 85 line screens for black & white newspaper reproduction, and they can be resized, either 50% larger or smaller with no degradation in image quality or moire effect. Please note that detailed information about each project is available on the Pritzker Prize web site (pritzkerprize.com). The photo credit line shown next to each photo should appear adjacent to the photos when published. All photos are through the courtesy of Utzon Architects who provided the same images to the publisher of Utzon by Richard Weston. Photo by David Messent 04 Sydney Opera House Sydney, Australia 1957-1973 Photo by David Messent 05 Sydney Opera House Sydney, Australia 1957-1973 -

The Role of Alvar Aalto in Developing the Maturity of Jørn Utzon's Work

Alvar Aalto Researchers’ Network Seminar – Why Aalto? 9-10 June 2017, Jyväskylä, Finland Aalto through young Utzon’s eyes: The role of Alvar Aalto in developing the maturity of Jørn Utzon’s work Chiu Chen-Yu Assistant Professor Department of Architecture, Bilkent University +90 5316 146 326 +90 312 290 2590 [email protected] FF 206, Department of Architecture Bilkent University, 06800 Ankara, TURKEY Aalto through young Utzon’s eyes: The role of Alvar Aalto in developing the maturity of Jørn Utzon’s work CHIU Chen-Yu, Bilkent University Helyaneh Aboutalebi Tabrizi, Bilkent University Introduction There is no doubt that the work of Alvar Aalto (1898-1976) played an important role in the maturity of architectural design of Jørn Utzon (1918-2008). Despite Utzon openly and repeatedly admitted his learning from Aalto, what was the interrelationship between these two master architects, what was Utzon’s perception of Aalto’s work and how Utzon interpreted the ideas and ideals received from Aalto’s work, are all unknown and unheard. By surveying the architectural collection both of Aalto and Utzon, this article reconstructs their communications in-between and reviews Utzon’s study on Aalto’s work through his own photography images and book collection, as well as building excursions. In addition, it constructs a series of analytical comparisons between the studied work of Aalto and Utzon’s architectural creation. The found analogies in-between are served as the rationale for arguing Utzon’s learning from Aalto. However, Utzon did not simply imitate the manners of Aalto, and Utzon seemed to interpret the received concepts from Aalto with his own beliefs and interests, as well as with other influences. -

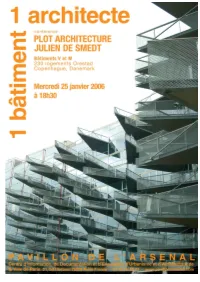

Julien De Smedt, Architect

Cycle de conférences «1 architecte, 1 bâtiment» “histoire d’un projet - commande - contraintes construction - maîtrise d’ouvrage - métier d’architecte règlements...” Nous avons souhaité lancer en l’an 2000, un cycle intitulé, « 1 architecte - 1 bâtiment » au cours duquel des architectes reconnus sont venus et viendront au Pavillon de l’Arsenal évoquer l’histoire d’un de leurs projets réalisé en France ou ailleurs. Ce cycle de conférence doit permettre au grand public de comprendre comment se fait l’architecture et de lui faire découvrir le métier d’architecte à travers l’histoire d’un projet. Les maîtres d’œuvre invités, français ou étrangers, présenteront chronologique- ment toute l’histoire d’un de leurs projets, de la commande jusqu’à sa réalisation et à son appropriation par l’utilisateur. Ces conférences permettent de mieux appréhender les contraintes rencontrées par les maîtres d’œuvre, de découvrir les liens tissés avec le maître d’ouvrage et les différents intervenants, de connaître les réflexions des architectes sur la comande et sur les règlements qui varient selon les villes, selon les pays. Régulièrement d’autres architectes viendront ainsi nous parler, de projets, d’échelles et de programmes différents. Dominique ALBA Directrice Générale du Pavillon de l’Arsenal Sommaire Plot architecture page 1 Housing building V page 2 Housing building M page 4 OL mountain dwellings page 6 Julien de Smedt page 9 Cycle de conférences, rappel page 10 PLOT was founded in order to develop an architectural practice that turns intense research and analysis of practical as well as theoretical issues into the driving forces of design.