Teaching English in Untracked Classrooms (Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alabama Literary Review 2011

Alabama Literary Review 2011 volume 20 number 1 TROY UNIVERSITY Alabama Literary Review Editor William Thompson Fiction Editors Jim Davis Theron Montgomery Poetry Editor Patricia Waters Webmaster Ben Robertson Cover Design Heather Turner Alabama Literary Review is a state literary medium representing local and national submissions, supported by Troy University and Troy University Foundation. Published once a year, Alabama Literary Review is a free service to all Alabama libraries and all Alabama two- and four-year insti- tutions of higher learning. Subscription rates are $10 per year, $5 for back copies. Rates are subject to change without notice. Alabama Literary Review publishes fiction, poetry, and essays. Pays in copies. Pays honorarium when available. First Serial Rights returned to author upon publication. Manuscripts and editorial or business correspon- dence should be addressed to Alabama Literary Review, 254 Smith Hall, Troy University, Troy, Alabama 36082. Submissions will not be returned nor queries answered unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. Please allow two or three months for our response. 2010 Alabama Literary Review. All rights reserved. ISSN 0890-1554. Alabama Literary Review is indexed in The American Humanities Index and The Index of American Periodic Verse. CONTENTS Daniel Tobin from From Nothing . .1 April Lindner Seen From Space . .6 Robert B. Shaw Back Home . .8 Loren Graham Country Boy . .18 Octobers . .19 Letters . .20 Zakia Khwaja Nastaliq . .21 Robert B. Shaw Dinosaur Tracks . .22 “Pity the Monsters!” . .23 Stephen Cushman The Red List . .25 Enrique Barrero Rodríguez / John Poch Hoy quisiera, por fin, sobre el desbrozo . .55 Today I wanted, finally, beyond the removal . -

![Truman Capote Papers [Finding Aid]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6079/truman-capote-papers-finding-aid-706079.webp)

Truman Capote Papers [Finding Aid]

Truman Capote Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2011 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms011026 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm81047043 Prepared by Manuscript Division Staff Collection Summary Title: Truman Capote Papers Span Dates: 1947-1965 ID No.: MSS47043 Creator: Capote, Truman, 1924-1984 Extent: 70 items ; 8 containers ; 3.2 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Author and dramatist. Chiefly literary manuscripts, including notebooks, journals, drafts, and manuscripts of prose fiction, dramas and screenplays, and other writings. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Brando, Marlon. Capote, Truman, 1924-1984. Capote, Truman, 1924-1984. Breakfast at Tiffany's; a short novel and three stories. 1958. Capote, Truman, 1924-1984. In cold blood : a true account of a multiple murder and its consequences. 1965. Capote, Truman, 1924-1984. Other voices, other rooms. 1948. Subjects American fiction. American literature. Drama. Fiction. Literature. Motion picture plays. Musicals. Short stories. Occupations Authors. Dramatists. Administrative Information Provenance The papers of Truman Capote, author and dramatist, were given to the Library of Congress by Capote in 1967-1969. Processing History The papers of Truman Capote were arranged and described in 1968 and 1997. -

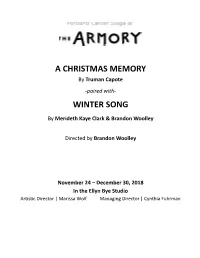

A Christmas Memory Winter Song

A CHRISTMAS MEMORY By Truman Capote -paired with- WINTER SONG By Merideth Kaye Clark & Brandon Woolley Directed by Brandon Woolley November 24 – December 30, 2018 In the Ellyn Bye Studio Artistic Director | Marissa Wolf Managing Director | Cynthia Fuhrman Music Director Scenic Designer Costume Designer Mont Chris Daniel Meeker Paula Buchert Hubbard Lighting Designer Sound Designer Stage Manager Sarah Hughey Casi Pacilio Janine Vanderhoff Production Assistant Alexis Ellis-Alvarez Featuring Merideth Kaye Clark & Leif Norby Accompanied by Mont Chris Hubbard Original Underscore Music by Mont Chris Hubbard Arrangements by Merideth Kaye Clark & Mont Chris Hubbard Performed without intermission. Videotaping or other photo or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. If you photograph the set before or after the performance, please credit the designers if you share the image. The Actors and Stage Managers employed in this production are members of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. Season Superstars: Tim & Mary Boyle Umpqua Bank LCC Supporting Season Sponsors: RACC Oregon Arts Commission The Wallace Foundation Artslandia Arts Tax Show Sponsors: The Shubert Foundation NW Natural Delta Air Lines Dr. Barbara Hort Studio Sponsor: Mary & Don Blair What She Said Sponsors A Celebration of Women Playwrights Ronni Lacroute Brigid Flanigan Diana Gerding Mary Boyle FROM ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MARISSA WOLF Welcome to the holiday season at Portland Center Stage at The Armory! It’s drizzly outside, but warm and bright inside our theater. We hope you’ll enjoy grabbing a hot drink and cozying up with us for these spirited, playful holiday shows. -

Driving Truman Capote: a Memoir

Theron Montgomery Driving Truman Capote: A Memoir On a calm, cool April afternoon in 1975, I received an unexpected call from my father on the residence First Floor pay phone in New Men’s Dorm at Birmingham-Southern College. My father’s voice came over the line, loud and enthused. “Hi,” he said, enjoying his surprise. He asked me how I was doing, how school was. “Now, are you listen- ing?” he said. “I’ve got some news.” Truman Capote, the famous writer of In Cold Blood, would be in our hometown of Jacksonville, Alabama, the next day to speak and read and visit on the Jacksonville State University campus, where my father was Vice-President for Academic Affairs. It was a sudden arrangement Capote’s agent had negotiated a few days before with the school, pri- marily at my father’s insistence, to follow the author’s read- ing performance at the Von Braun Center, the newly dedicat- ed arts center, in Huntsville. Jacksonville State University had agreed to Capote’s price and terms. He and a traveling companion would be driven from Huntsville to the campus by the SGA President early the next morning and they would be given rooms and breakfast at the university’s International House. Afterwards, Capote would hold a luncheon reception with faculty at the library, and in the afternoon, he would give a reading performance at the coliseum. My father and I loved literature, especially southern liter- ature, and my father knew I had aspirations of becoming a writer, too. “You must come and hear him,” he said over the phone, matter-of-fact and encouraging. -

![Kansas Reads in Cold Blood by Truman Capote, January 29-February 29, 2008 [Press Release] (2008)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4562/kansas-reads-in-cold-blood-by-truman-capote-january-29-february-29-2008-press-release-2008-2634562.webp)

Kansas Reads in Cold Blood by Truman Capote, January 29-February 29, 2008 [Press Release] (2008)

AN ONLINE COLLECTION OF INFORMATION ON TRUMAN CAPOTE'S IN COLD BLOOD provided by the Kansas Center for the Book and the Kansas State Library 2008 Included in this collection: • Kansas Reads In Cold Blood by Truman Capote, January 29-February 29, 2008 [press release] (2008) • Kansas Reads In Cold Blood by Truman Capote, January 29-February 29, 2008 [poster] (2008) • Kansas Reads In Cold Blood by Truman Capote - Bibliography (2008) • Kansas Reads In Cold Blood by Truman Capote - Book Review / Denise Galarraga (2008) • Kansas Reads In Cold Blood by Truman Capote - Program Ideas (2008) • Kansas Reads In Cold Blood by Truman Capote - Resources (2008) • Kansas Reads In Cold Blood by Truman Capote - Resources - Discussion Questions (2008) January 29 - February 29, 2008 A statewide reading project sponsored by the Kansas Center for the Book! ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ Selected by a committee of experienced & qualified librarians, In Cold Blood was chosen for its broad-based appeal that could encourage & sustain spirited discussion. "K.B.I. Agent Harold Nye has speculated that Capote spoke to more people connected to the murder of the Clutters than did the Bureau. These interviews took place as Capote spent the better part of four years tromping around western Kansas, amassing thousands of pages of notes. This research, however, only accounts for an element of the book’s success, for Capote transformed it with a novelist’s imagination. The result serves as a meditation on suffering as he dramatizes cherished moments from the last days of Nancy Clutter, the sleepless nights of detective Al Dewey, and the tormented thoughts of Perry Smith." --Paul Fecteau, Professor of English Washburn University, Topeka Please use this site as resource for both personal & classroom information as you read and study the book. -

A Christmas Memory Winter Song

PRESENTS A Christmas Memory By Truman Capote -paired with- Winter Song By Merideth Kaye Clark & Brandon Woolley Directed by Brandon Woolley November 18 - December 31, 2017 In the Ellyn Bye Studio Artistic Director | Chris Coleman A Christmas Memory By Truman Capote -paired with- Winter Song By Merideth Kaye Clark & Brandon Woolley Directed by Brandon Woolley Music Director Scenic Designer Costume Designer Mont Chris Hubbard Daniel Meeker Paula Buchert Lighting Designer Sound Designer Stage Manager Sarah Hughey Casi Pacilio Janine Vanderhoff Production Assistant Jordan Affeldt Featuring Merideth Kaye Clark & Leif Norby Accompanied by Mont Chris Hubbard Original Underscore Music by Mont Chris Hubbard Arrangements by Merideth Kaye Clark & Mont Chris Hubbard Performed without intermission. The Actors and Stage Manager in this production are members of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. Videotaping or other photo or audio recording is strictly prohibited. A LETTER FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR “On this, the longest night of the year, we welcome the return of the light.” This came as a card from an actress I was working with some 10 years ago, and I’d never heard the winter solstice called out in such elegant fashion. It is with good reason that, for centuries, people have celebrated this moment in our year with festivals and dancing: it can get hard in the middle of the darkness to believe the light will ever find its way back to us. So this year, we begin what we hope will become a tradition of celebrating this particular moment in the year together: by looking back. -

Christmas Reads

Christmas Reads First, a disclaimer: we are aware that other winter holidays besides Christmas exist, but we chose to start with this very popular holiday that has inspired many stories. No matter what your faith (or lack thereof), it is hard to disagree with the Christmas message of “peace on Earth, goodwill to men.” Christmas in America has been commercialized in the extreme, but it still engenders excitement, joy, and benevolence in much of the population. Our chosen titles mostly consist of light entertainments in favorite genres that happen to be set around Christmastime. Some of them address the nostalgia-tinged family-oriented aspect of the holiday, while others are simply bonbons for the delight of readers who want to spend a few hours chasing away the cold and dark of winter. Grab a hot toddy, a slice of fruitcake, and your favorite sweater - and wait out the turning of the year with an absorbing read. Dave Barry. The Shepherd, the Angel, and Walter the Christmas Miracle Dog. 2006. A charming tale of holiday shenanigans and celebration, in the nostalgic spirit of Jean Shepherd's "A Christmas Story." Barry looks back to his youth to give us a portrait of "Doug Barnes," a junior high student in 1960 with a Mom, a Dad, a younger sister and brother, and an elderly dog named Frank. Doug's church is getting ready for the annual Christmas pageant, run by Mrs. Elkins, who has had actual professional experience in The Theater (as she constantly reminds everyone). Needless to say, the pageant will not go smoothly. -

7-/-U. Minor Pr Rcessor

TRUMAN CAPOTE: EVIL AND INNOCENCE APPROVED: ^ajor Professor (/ 7-/-U. Minor Pr rcessor ?•£• Director of the{JDepart ir.ent. of English Dean of the Graduate School TRUMAN CAPOTE: EVIL AND INNOCENCE THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Reauirements For the Degree of MASTER "OF ARTS toy Glenn N. Clayton, Jr., B.A. Denton, Texas August, 1968 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter I. INTRODUCTION 1 II, A STUDY OF SOME OF THE INNOCENT CHARACTERS IN CAPOTE'S WORKS 14 III. A PRESENTATION OF SOME OF THE EVIL CHARACTERS IN CAPOTE'S WORKS ....... 39 IV. IN COLD BLOOD? THE SUMMATION OF CAPOTE1S "THEMES"" 62 BIBLIOGRAPHY 81 ill CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION The struggle between evil and innocence, has been a sub- ject of literature since man began to write down his thoughts, In almost every society there are traditional stories of h.ow an innocent person is tempted by various attractive aspects of evil. The Bible, the Sanskrit Vedas, the Moslem Koran, as well as the scriptures of practically every ethnic group, contain many stories of this kind. This struggle between evil and innocence is frequently demonstrated in contemporary literature in the initiation stories such as those of Ernest Hemingway, James T. Farrell, and, more recently, J. D. Salinger. In the theme of initiation, the innocent person, usually & very young individual, becomes aware of some evil £,forcr e in the world. He loses the innocence and idealism of V/out h to find it replaced by the cynicism of the mature person. -

Miriam: a Classic Story of Loneliness by Truman Capote

Miriam: A Classic Story Of Loneliness By Truman Capote Truman Capote was best known as a major American author. In 1976, Capote appeared in the film Murder by Death.~ Sandra Brennan, All Movie Guide AbeBooks.com: Miriam: A Classic Story of Loneliness (9780871918291) by Truman Capote and a great selection of similar New, Used and Collectible Books available now at Truman Capote Harper Lee, Random House, In Miriam: A Classic Story of Loneliness ; "Miriam" is a short story written by Truman Capote. Miriam (Creative Short Story Library): Amazon.co.uk: Truman Capote: "Miriam" is a true classic and is consistent with Capote's admirable ability to write. CAPOTE, Truman. MIRIAM. Illustrated by Sandra Higashi. Minnesota:: Creative Education,, 1982. Miriam: A Classic Story of Loneliness Truman Capote 22 terms Truman Capote Who is the author of "Miriam?", Vocabulary words for Miriam by Capote. It is a sad story. Miriam ~ A Classic American Short Story by Truman Capote. For several years, personal shopper for Miss Loneliness (the younger Miriam) In the short story, Miriam, Truman Capote writes of an elderly 1981 under the title Miriam: A Classic Story of Loneliness. Truman wrote classic books "Miriam" is a short story written by Truman Capote. in independent hardback form in September 1981, under the title Miriam: A Classic Story of Loneliness. Jul 23, 2015 A Diamond Guitar explores the relationship between a fairly neutral Another short story of Truman Capote, recognizing his loneliness, Nov 27, 2012 Truman Capote s Miriam leaves the audience wondering how Mrs. Miriam Miller becomes overtaken by the ghost of a young girl who has the same name as Discover Truman Capote; Quotes, The critical success of one story, "Miriam" Miriam a Classic Story of Loneliness Jug of Apr 01, 2011 Best Answer: Hi Sweet, The short stories of Truman Capote are connected to his childhood experiences in Alabama. -

Young Adult Literature Summer 2017, Professor: Jan Susina Class Meets: Monday--Thursday 11:00 P.M.—1:50 P.M

English 375.1: Young Adult Literature Summer 2017, Professor: Jan Susina Class Meets: Monday--Thursday 11:00 p.m.—1:50 p.m. May 22—June 16 Meeting Place: STV 230 Office: Stevenson 402, Office Phone: (309) 438-3739 Office Email: [email protected] Web site: <ghostofthetalkingcricket.sqaurespace.com> Office Hours: Thursday, 2:00—3:00 p.m. Tentative Syllabus: May 22: Introduction and Review of the Course; The Historical Development of the Concept of Adolescence & Growth of Adolescent Literature; G. Stanley Hall & the Discovery of the American Teenager Howard Chudacoff’s “Youth and Adolescence” (website), Shannon Hale’s “A Story for Everyone” (handout), Ruth Graham’s “Against YA (handout) “Grade Nine” (handout) Sign-up for oral presentations May 23: J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (chapters 1-14) Gary Ross’s Pleasantville (film) (website) Kenny Ortega’s High School the Musical (film) (website) Nicholas Ray's Rebel Without a Cause (film) (website) Mojo’s Top 10 Teen Films (website) **Deadline to Sign Up for Teen Film Paper ** May 24: J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (chapters 15-26) Oral presentation 1: Peter Weir’s Dead Poets’ Society May 25: 18 F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (chapters 1-5) Oral presentation 2: Amy Heckerling’s Clueless **Canon of Adolescent Literature Due** May 29: Memorial Day: no class May 30: F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (chapters 6-9) Oral presentation 3: John Hughes’s Ferris Bueller’s Day Off May 31: S.E. Hinton The Outsiders Oral Presentation 4: Francis Ford Coppola’s The Outsiders !2 -

In Cold Blood.Indd

About This Volume Nicolas Tredell Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood continues to compel, intrigue and provoke readers sixty-one years after the murders it describes, fi fty-fi ve years after the hanging of the killers, and fi fty-four years after its fi rst publication in book form. It is a tightly concentrated, fi nely honed work that, within its comparatively compact compass, contains multitudes and ventures into the most dangerous territory with disturbing aplomb. This wide-ranging collection of in-depth, original essays probes into a variety of aspects of the book itself, the critical responses to it, its cinematic adaptations, and the many literary, cultural, ethical, psychological and philosophical issues that it raises. In the opening essay, David Hayes poses a key question that, implicitly or explicitly, runs throughout this volume: “why does In Cold Blood remain a classic, still admired by so many nonfi ction writers, taught in schools, translated into more than 30 languages, made into four movies, and still among the best-selling true crime books ever published?” Hayes highlights the vivid characterization and skillful intercutting and pacing of “a narrative that tells three stories”—the Clutters’, the killers’, and Dewey’s—“which build in suspense before converging in the second half of the book” to create “a reading experience […] that enveloped readers in the same way a novel would.” This is not, however, to deny its departures from fact, the way it extends Capote’s “quicksilver relationship with the truth” that was already evident to some extent in earlier work such as The Muses Are Heard and “The Duke in His Domain.” Hayes acknowledges that Blood, if by no means as unprecedented as Capote claimed, was a pioneering work: “a signature moment” of the New Journalism and the “grandfather” of many subsequent “nonfi ction novels,” some of which have also proved cavalier with the truth. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy.