7-/-U. Minor Pr Rcessor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writers Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Monica Ali Isabel Allende Martin Amis Kurt Andersen K

Writers Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Monica Ali Isabel Allende Martin Amis Kurt Andersen K. A. Applegate Jeffrey Archer Diana Athill Paul Auster Wasi Ahmed Victoria Aveyard Kevin Baker Mark Allen Baker Nicholson Baker Iain Banks Russell Banks Julian Barnes Andrea Barrett Max Barry Sebastian Barry Louis Bayard Peter Behrens Elizabeth Berg Wendell Berry Maeve Binchy Dustin Lance Black Holly Black Amy Bloom Chris Bohjalian Roberto Bolano S. J. Bolton William Boyd T. C. Boyle John Boyne Paula Brackston Adam Braver Libba Bray Alan Brennert Andre Brink Max Brooks Dan Brown Don Brown www.downloadexcelfiles.com Christopher Buckley John Burdett James Lee Burke Augusten Burroughs A. S. Byatt Bhalchandra Nemade Peter Cameron W. Bruce Cameron Jacqueline Carey Peter Carey Ron Carlson Stephen L. Carter Eleanor Catton Michael Chabon Diane Chamberlain Jung Chang Kate Christensen Dan Chaon Kelly Cherry Tracy Chevalier Noam Chomsky Tom Clancy Cassandra Clare Susanna Clarke Chris Cleave Ernest Cline Harlan Coben Paulo Coelho J. M. Coetzee Eoin Colfer Suzanne Collins Michael Connelly Pat Conroy Claire Cook Bernard Cornwell Douglas Coupland Michael Cox Jim Crace Michael Crichton Justin Cronin John Crowley Clive Cussler Fred D'Aguiar www.downloadexcelfiles.com Sandra Dallas Edwidge Danticat Kathryn Davis Richard Dawkins Jonathan Dee Frank Delaney Charles de Lint Tatiana de Rosnay Kiran Desai Pete Dexter Anita Diamant Junot Diaz Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni E. L. Doctorow Ivan Doig Stephen R. Donaldson Sara Donati Jennifer Donnelly Emma Donoghue Keith Donohue Roddy Doyle Margaret Drabble Dinesh D'Souza John Dufresne Sarah Dunant Helen Dunmore Mark Dunn James Dashner Elisabetta Dami Jennifer Egan Dave Eggers Tan Twan Eng Louise Erdrich Eugene Dubois Diana Evans Percival Everett J. -

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

Alabama Literary Review 2011

Alabama Literary Review 2011 volume 20 number 1 TROY UNIVERSITY Alabama Literary Review Editor William Thompson Fiction Editors Jim Davis Theron Montgomery Poetry Editor Patricia Waters Webmaster Ben Robertson Cover Design Heather Turner Alabama Literary Review is a state literary medium representing local and national submissions, supported by Troy University and Troy University Foundation. Published once a year, Alabama Literary Review is a free service to all Alabama libraries and all Alabama two- and four-year insti- tutions of higher learning. Subscription rates are $10 per year, $5 for back copies. Rates are subject to change without notice. Alabama Literary Review publishes fiction, poetry, and essays. Pays in copies. Pays honorarium when available. First Serial Rights returned to author upon publication. Manuscripts and editorial or business correspon- dence should be addressed to Alabama Literary Review, 254 Smith Hall, Troy University, Troy, Alabama 36082. Submissions will not be returned nor queries answered unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. Please allow two or three months for our response. 2010 Alabama Literary Review. All rights reserved. ISSN 0890-1554. Alabama Literary Review is indexed in The American Humanities Index and The Index of American Periodic Verse. CONTENTS Daniel Tobin from From Nothing . .1 April Lindner Seen From Space . .6 Robert B. Shaw Back Home . .8 Loren Graham Country Boy . .18 Octobers . .19 Letters . .20 Zakia Khwaja Nastaliq . .21 Robert B. Shaw Dinosaur Tracks . .22 “Pity the Monsters!” . .23 Stephen Cushman The Red List . .25 Enrique Barrero Rodríguez / John Poch Hoy quisiera, por fin, sobre el desbrozo . .55 Today I wanted, finally, beyond the removal . -

Truman Capote's Early Short Stories Or the Fight of a Writer to Find His

Truman Capote’s Early Short Stories or The Fight of a Writer to Find His Own Voice Emilio Cañadas Rodríguez Universidad Alfonso X El Sabio (Madrid) Abstract Truman Capote’s early stories have not been studied in depth so far and literary studies on Truman Capote’s short stories start with his first collection “A Tree of Night and Other Stories”, published in 1949. Stories previous to 1945 such as “The Walls Are Cold”, “A Mink’s of One’s Own” or “The Shape of things” are basically to be discovered and their relevance lie on the fact of being successful narrative exercises that focus more in the construction of characters than in the action itself. They are stories to be read “on one sitting” and stories that make the reader foresee Capote’s skilful short narrative in the future. It is our aim, then, in this paper to present the first three ever written stories by Truman Capote, to analyse them and to remark their relevance for Capote’s literary universe. Dwarfed and darkened by narrative masterpieces such as In Cold Blood (1965) or Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948) , Truman Capote’s short stories have never been as acclaimed or studied as his novels. Literary critics have predominantly focussed their criticism on Capote’s work as a novelist emphasizing on the “Gothicism” and “the form of horror” in Other Voices, Other Rooms or the author’s innovative techniques in In Cold Blood.1 However, apart from the complete research of Kenneth T. Reed, there are several studies on Capote’s whole literary career like William Nance’s or Helen S. -

BTC Catalog 172.Pdf

Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. ~ Catalog 172 ~ First Books & Before 112 Nicholson Rd., Gloucester City NJ 08030 ~ (856) 456-8008 ~ [email protected] Terms of Sale: Images are not to scale. All books are returnable within ten days if returned in the same condition as sent. Books may be reserved by telephone, fax, or email. All items subject to prior sale. Payment should accompany order if you are unknown to us. Customers known to us will be invoiced with payment due in 30 days. Payment schedule may be adjusted for larger purchases. Institutions will be billed to meet their requirements. We accept checks, VISA, MASTERCARD, AMERICAN EXPRESS, DISCOVER, and PayPal. Gift certificates available. Domestic orders from this catalog will be shipped gratis via UPS Ground or USPS Priority Mail; expedited and overseas orders will be sent at cost. All items insured. NJ residents please add 7% sales tax. Member ABAA, ILAB. Artwork by Tom Bloom. © 2011 Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. www.betweenthecovers.com After 171 catalogs, we’ve finally gotten around to a staple of the same). This is not one of them, nor does it pretend to be. bookselling industry, the “First Books” catalog. But we decided to give Rather, it is an assemblage of current inventory with an eye toward it a new twist... examining the question, “Where does an author’s career begin?” In the The collecting sub-genre of authors’ first books, a time-honored following pages we have tried to juxtapose first books with more obscure tradition, is complicated by taxonomic problems – what constitutes an (and usually very inexpensive), pre-first book material. -

Serial Historiography: Literature, Narrative History, and the Anxiety of Truth

SERIAL HISTORIOGRAPHY: LITERATURE, NARRATIVE HISTORY, AND THE ANXIETY OF TRUTH James Benjamin Bolling A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Minrose Gwin Jennifer Ho Megan Matchinske John McGowan Timothy Marr ©2016 James Benjamin Bolling ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Ben Bolling: Serial Historiography: Literature, Narrative History, and the Anxiety of Truth (Under the direction of Megan Matchinske) Dismissing history’s truths, Hayden White provocatively asserts that there is an “inexpugnable relativity” in every representation of the past. In the current dialogue between literary scholars and historical empiricists, postmodern theorists assert that narrative is enclosed, moribund, and impermeable to the fluid demands of history. My critical intervention frames history as a recursive, performative process through historical and critical analysis of the narrative function of seriality. Seriality, through the material distribution of texts in discrete components, gives rise to a constellation of entimed narrative strategies that provide a template for human experience. I argue that serial form is both fundamental to the project of history and intrinsically subjective. Rather than foreclosing the historiographic relevance of storytelling, my reading of serials from comic books to the fiction of William Faulkner foregrounds the possibilities of narrative to remain open, contingent, and responsive to the potential fortuities of historiography. In the post-9/11 literary and historical landscape, conceiving historiography as a serialized, performative enterprise controverts prevailing models of hermeneutic suspicion that dominate both literary and historiographic skepticism of narrative truth claims and revives an ethics responsive to the raucous demands of the past. -

![Truman Capote Papers [Finding Aid]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6079/truman-capote-papers-finding-aid-706079.webp)

Truman Capote Papers [Finding Aid]

Truman Capote Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2011 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms011026 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm81047043 Prepared by Manuscript Division Staff Collection Summary Title: Truman Capote Papers Span Dates: 1947-1965 ID No.: MSS47043 Creator: Capote, Truman, 1924-1984 Extent: 70 items ; 8 containers ; 3.2 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Author and dramatist. Chiefly literary manuscripts, including notebooks, journals, drafts, and manuscripts of prose fiction, dramas and screenplays, and other writings. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Brando, Marlon. Capote, Truman, 1924-1984. Capote, Truman, 1924-1984. Breakfast at Tiffany's; a short novel and three stories. 1958. Capote, Truman, 1924-1984. In cold blood : a true account of a multiple murder and its consequences. 1965. Capote, Truman, 1924-1984. Other voices, other rooms. 1948. Subjects American fiction. American literature. Drama. Fiction. Literature. Motion picture plays. Musicals. Short stories. Occupations Authors. Dramatists. Administrative Information Provenance The papers of Truman Capote, author and dramatist, were given to the Library of Congress by Capote in 1967-1969. Processing History The papers of Truman Capote were arranged and described in 1968 and 1997. -

Naturalism, the New Journalism, and the Tradition of the Modern American Fact-Based Homicide Novel

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. U·M·I University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml48106-1346 USA 3131761-4700 800!521-0600 Order Number 9406702 Naturalism, the new journalism, and the tradition of the modern American fact-based homicide novel Whited, Lana Ann, Ph.D. -

To Download the PDF File

Vi • 1n• tudents like CS; • SIC, pool, city / By Gloria Pena rate, gymnastics, volleyball, , Have you noticed five new stu- r pingpong, stamp collecting, mo I '• dents roamang the halls within del airplane, playing the flute B the last three weeks? Well, they and guitar, and all seemed to be were not here permanently, but enthusiastic about girls were exchange students from Guatemala, Central America, The school here is different vasatang Shreveport, The Louisi from those in Guatemala in the ana Jaycees sponsored these way that here the students go to students and the people they are the classes, where as in Guate staying with will in turn visit mala, the teachers change class Guatamala and stay with a famaly rooms. One sa ad that ·'here the there. students are for the teachers, Whale visitang Shreveport they where there, the teachers are for -did such !hangs as visit a farm in the students." Three of the stu ~aptain ~'trrur 11igtp ..ctpool Texas, where they had a wiener dents are still in high school, roast ; visit Barksdale A ir Force while the other two are in col Base· take an excursion to lege, one studying Architecture Shreve Square, go to parties; and the other studying Business Volume IX Shreveport, La., December 15, 1975 Number 5 take in sO'me skating; and one Administration. even had the experaence of going flying with Mrs. Helen Wray. The students also went shop ping at Southpark Mall of which Christmas brings gifts; they were totally amazed, and at Eastgate Shopping Center by Captain Shreve. One even catalogue offers I aug hs splurged and bought $30 worth By Sandra Braswell $2,250,000. -

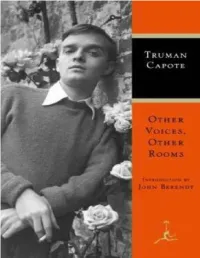

Other Voices, Other Rooms Came to Him in the Form of a Revelation During a Walk in the Woods

Table of Contents Title Page Dedication Epigraph INTRODUCTION PART ONE ONE TWO THREE FOUR FIVE PART TWO SIX SEVEN EIGHT NINE TEN ELEVEN PART THREE TWELVE About the Author Copyright Page FOR NEWTON ARVIN The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked. Who can know it? JEREMIAH 17:9 INTRODUCTION John Berendt As Truman Capote remembered it years later, the idea for Other Voices, Other Rooms came to him in the form of a revelation during a walk in the woods. He was twenty-one, living with relatives in rural Alabama, and working on a novel that he had begun to fear was “thin, clever, unfelt.” One afternoon, he went for a stroll along the banks of a stream far from home, pondering what to do about it, when he came upon an abandoned mill that brought back memories from his early childhood. The remembered images sent his mind reeling, causing him to slip into a “creative coma” during which a completely different book presented itself and began to take shape, virtually in its entirety. Reaching home after dark, he skipped supper, put the manuscript of the troublesome unfinished novel into a bottom bureau drawer (it was entitled “Summer Crossing,” never published, later lost), climbed into bed with a handful of pencils and a pad of paper, and wrote: “Other Voices, Other Rooms—a novel by Truman Capote. Now a traveler must make his way to Noon City by the best means he can . .”1 Whether or not Capote’s remarkable first novel came to him as he said it did, in a spontaneous flow of words as if dictated by “a voice from a cloud,” the work that emerged two years later was as lyrical and rich in poetic imagery as if it had been written by a writer possessed. -

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction Honors a Distinguished Work of Fiction by an American Author, Preferably Dealing with American Life

Pulitzer Prize Winners Named after Hungarian newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer, the Pulitzer Prize for fiction honors a distinguished work of fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life. Chosen from a selection of 800 titles by five letter juries since 1918, the award has become one of the most prestigious awards in America for fiction. Holdings found in the library are featured in red. 2017 The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead 2016 The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen 2015 All the Light we Cannot See by Anthony Doerr 2014 The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt 2013: The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 2012: No prize (no majority vote reached) 2011: A visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 2010:Tinkers by Paul Harding 2009:Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 2008:The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 2007:The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2006:March by Geraldine Brooks 2005 Gilead: A Novel, by Marilynne Robinson 2004 The Known World by Edward Jones 2003 Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2002 Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2001 The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon 2000 Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 1999 The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1998 American Pastoral by Philip Roth 1997 Martin Dressler: The Tale of an American Dreamer by Stephan Milhauser 1996 Independence Day by Richard Ford 1995 The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 1994 The Shipping News by E. Anne Proulx 1993 A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain by Robert Olen Butler 1992 A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley -

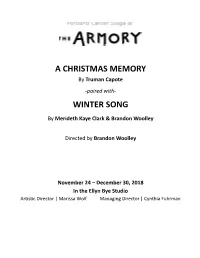

A Christmas Memory Winter Song

A CHRISTMAS MEMORY By Truman Capote -paired with- WINTER SONG By Merideth Kaye Clark & Brandon Woolley Directed by Brandon Woolley November 24 – December 30, 2018 In the Ellyn Bye Studio Artistic Director | Marissa Wolf Managing Director | Cynthia Fuhrman Music Director Scenic Designer Costume Designer Mont Chris Daniel Meeker Paula Buchert Hubbard Lighting Designer Sound Designer Stage Manager Sarah Hughey Casi Pacilio Janine Vanderhoff Production Assistant Alexis Ellis-Alvarez Featuring Merideth Kaye Clark & Leif Norby Accompanied by Mont Chris Hubbard Original Underscore Music by Mont Chris Hubbard Arrangements by Merideth Kaye Clark & Mont Chris Hubbard Performed without intermission. Videotaping or other photo or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. If you photograph the set before or after the performance, please credit the designers if you share the image. The Actors and Stage Managers employed in this production are members of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. Season Superstars: Tim & Mary Boyle Umpqua Bank LCC Supporting Season Sponsors: RACC Oregon Arts Commission The Wallace Foundation Artslandia Arts Tax Show Sponsors: The Shubert Foundation NW Natural Delta Air Lines Dr. Barbara Hort Studio Sponsor: Mary & Don Blair What She Said Sponsors A Celebration of Women Playwrights Ronni Lacroute Brigid Flanigan Diana Gerding Mary Boyle FROM ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MARISSA WOLF Welcome to the holiday season at Portland Center Stage at The Armory! It’s drizzly outside, but warm and bright inside our theater. We hope you’ll enjoy grabbing a hot drink and cozying up with us for these spirited, playful holiday shows.