Truman Capote's Early Short Stories Or the Fight of a Writer to Find His

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Download the PDF File

Vi • 1n• tudents like CS; • SIC, pool, city / By Gloria Pena rate, gymnastics, volleyball, , Have you noticed five new stu- r pingpong, stamp collecting, mo I '• dents roamang the halls within del airplane, playing the flute B the last three weeks? Well, they and guitar, and all seemed to be were not here permanently, but enthusiastic about girls were exchange students from Guatemala, Central America, The school here is different vasatang Shreveport, The Louisi from those in Guatemala in the ana Jaycees sponsored these way that here the students go to students and the people they are the classes, where as in Guate staying with will in turn visit mala, the teachers change class Guatamala and stay with a famaly rooms. One sa ad that ·'here the there. students are for the teachers, Whale visitang Shreveport they where there, the teachers are for -did such !hangs as visit a farm in the students." Three of the stu ~aptain ~'trrur 11igtp ..ctpool Texas, where they had a wiener dents are still in high school, roast ; visit Barksdale A ir Force while the other two are in col Base· take an excursion to lege, one studying Architecture Shreve Square, go to parties; and the other studying Business Volume IX Shreveport, La., December 15, 1975 Number 5 take in sO'me skating; and one Administration. even had the experaence of going flying with Mrs. Helen Wray. The students also went shop ping at Southpark Mall of which Christmas brings gifts; they were totally amazed, and at Eastgate Shopping Center by Captain Shreve. One even catalogue offers I aug hs splurged and bought $30 worth By Sandra Braswell $2,250,000. -

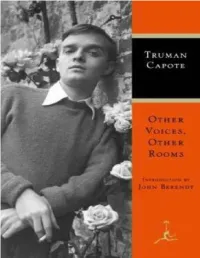

Other Voices, Other Rooms Came to Him in the Form of a Revelation During a Walk in the Woods

Table of Contents Title Page Dedication Epigraph INTRODUCTION PART ONE ONE TWO THREE FOUR FIVE PART TWO SIX SEVEN EIGHT NINE TEN ELEVEN PART THREE TWELVE About the Author Copyright Page FOR NEWTON ARVIN The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked. Who can know it? JEREMIAH 17:9 INTRODUCTION John Berendt As Truman Capote remembered it years later, the idea for Other Voices, Other Rooms came to him in the form of a revelation during a walk in the woods. He was twenty-one, living with relatives in rural Alabama, and working on a novel that he had begun to fear was “thin, clever, unfelt.” One afternoon, he went for a stroll along the banks of a stream far from home, pondering what to do about it, when he came upon an abandoned mill that brought back memories from his early childhood. The remembered images sent his mind reeling, causing him to slip into a “creative coma” during which a completely different book presented itself and began to take shape, virtually in its entirety. Reaching home after dark, he skipped supper, put the manuscript of the troublesome unfinished novel into a bottom bureau drawer (it was entitled “Summer Crossing,” never published, later lost), climbed into bed with a handful of pencils and a pad of paper, and wrote: “Other Voices, Other Rooms—a novel by Truman Capote. Now a traveler must make his way to Noon City by the best means he can . .”1 Whether or not Capote’s remarkable first novel came to him as he said it did, in a spontaneous flow of words as if dictated by “a voice from a cloud,” the work that emerged two years later was as lyrical and rich in poetic imagery as if it had been written by a writer possessed. -

Driving Truman Capote: a Memoir

Theron Montgomery Driving Truman Capote: A Memoir On a calm, cool April afternoon in 1975, I received an unexpected call from my father on the residence First Floor pay phone in New Men’s Dorm at Birmingham-Southern College. My father’s voice came over the line, loud and enthused. “Hi,” he said, enjoying his surprise. He asked me how I was doing, how school was. “Now, are you listen- ing?” he said. “I’ve got some news.” Truman Capote, the famous writer of In Cold Blood, would be in our hometown of Jacksonville, Alabama, the next day to speak and read and visit on the Jacksonville State University campus, where my father was Vice-President for Academic Affairs. It was a sudden arrangement Capote’s agent had negotiated a few days before with the school, pri- marily at my father’s insistence, to follow the author’s read- ing performance at the Von Braun Center, the newly dedicat- ed arts center, in Huntsville. Jacksonville State University had agreed to Capote’s price and terms. He and a traveling companion would be driven from Huntsville to the campus by the SGA President early the next morning and they would be given rooms and breakfast at the university’s International House. Afterwards, Capote would hold a luncheon reception with faculty at the library, and in the afternoon, he would give a reading performance at the coliseum. My father and I loved literature, especially southern liter- ature, and my father knew I had aspirations of becoming a writer, too. “You must come and hear him,” he said over the phone, matter-of-fact and encouraging. -

La Unidad Literaria En La Obra De Trumañ Capote

ELENA ORTELLS MONTÓN FICCIÓN Y NO-FICCIÓN: LA UNIDAD LITERARIA EN LA OBRA DE TRUMAÑ CAPOTE Anejo n.° XXXII de la Revista CUADERNOS DE FILOLOGÍA DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOLOGÍA INGLESA Y ALEMANA (Literatura norteamericana) FACULTAT DE FILOLOGÍA UNIVERSITAT DE VALENCIA ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN 1 CAPÍTULO 1. LA UNIDAD DE TEMAS EN LA OBRA LITERARIA DE TRUMAN CAPOTE 14 1.1. La teoría literaria de Truman Capote: el conflicto entre ficción y no-ficción 15 X 1.2. Las "dark short stories" 22 1.2.1. "Miriam" y "A Tree of Night" 24 1.2.2. "The Headless Hawk" y "Shut a Final Door" 26 1.2.3. "Master Misery" 31 1.3. Las "daylight stories" 33 1.3.1. "My Side of the Matter" 34 1.3.2. "Jug of Sil ver" y "Children on Their Birthdays" 35 1.4. Other Voices, Other Rooms 38 1.5. "A Diamond Guitar" 46 1.6. Local Color 47 1.7. The Grass Harp 51 1.8. "House of Flowers" 57 1.9. Evocaciones autobiográficas: "A Christmas Memory", The Thanksgiving Visitor, "Dazzle" y One Christmas 58 1.10. The Muses Are Heard 63 1.11. "The Duke in His Domain" 66 1.12. Observations 71 1.13. Breakfast at Tiffany's 71 1.14. "Among the Paths to Edén" 75 1.15. In Cold Blood 76 * 1.16. Music for Chamaleons 84 1.17. Answered Prayers 92 CAPÍTULO 2. LA MIRADA DEL NARRADOR 2.1. La problemática identificación autor/narrador 95 ,A 2.2. Hacia una clasificación de la figura del narrador 97 >0 2.2.1. -

February 10, 2009 (XVIII:5) Jack Clayton the INNOCENTS (1961, 100 Min)

February 10, 2009 (XVIII:5) Jack Clayton THE INNOCENTS (1961, 100 min) Directed and produced by Jack Clayton Based on the novella “The Turn of the Screw” by Henry James Screenplay by William Archibald and Truman Capote Additional scenes and dialogue by John Mortimer Original Music by Georges Auric Cinematography by Freddie Francis Film Editing by Jim Clark Art Direction by Wilfred Shingleton Deborah Kerr...Miss Giddens Peter Wyngarde...Peter Quint Megs Jenkins...Mrs. Grose Michael Redgrave...The Uncle Martin Stephens...Miles Pamela Franklin...Flora Clytie Jessop...Miss Jessel Isla Cameron...Anna JACK CLAYTON (March 1, 1921, Brighton, East Sussex, England, UK—February 26, 1995, Slough, Berkshire, England, UK) had 10 writing credits, some of which are In Cold Blood (1996), Other directing credits: Memento Mori (1992), The Lonely Passion of Voices, Other Rooms (1995), The Grass Harp (1995), One Judith Hearne (1987), Something Wicked This Way Comes Christmas (1994), The Glass House (1972), Laura (1968), In Cold (1983), The Great Gatsby (1974), Our Mother's House (1967), Blood (1967), The Innocents (1961), Breakfast at Tiffany's (1961), The Pumpkin Eater (1964), The Innocents (1961), Room at the Beat the Devil (1953), and Stazione Termini/Indiscretion of an Top (1959), The Bespoke Overcoat (1956), Naples Is a Battlefield American Wife (1953). (1944). DEBORAH KERR (September 30, 1921, Helensburgh, Scotland, JOHN MORTIMER (April 21, 1923, Hampstead, London, England, UK—October 16, 2007, Suffolk, England, UK) has 53 Acting UK—January 16, 2009, Oxfordshire, England, UK) has 59 Credits. She won an Honorary Oscar in 1994. Before that she had writing credits, some of which are In Love and War (2001), Don six best actress nominations: The Sundowners 1959, Separate Quixote (2000), Tea with Mussolini (1999), Cider with Rosie Tables (1958), Heaven Knows, Mr. -

THE GRASS HARP the Grass Harp Began Life in 1951 As a the Score Is a Constant Delight, with One Concert Version of His Musical Grossing- Novel by Truman Capote

THE GRASS HARP The Grass Harp began life in 1951 as a The score is a constant delight, with one concert version of his musical Grossing- novel by Truman Capote. Broadway pro- tuneful number after another. Claibe er’s (also written with Stephen Cole). ducer Saint Subber was taken with the Richardson was a wonderful and mostly When he brought me The Grass Harp I novel and asked Capote to do a stage unsung composer who should have been jumped at it – it was important to him to adaptation. Capote, who was still strug- a major name on Broadway. Kenward have it in print and sounding as it always gling as a young author, agreed. Directed Elmslie’s lyrics are enchanting and the should have sounded. But it’s now been by Robert Lewis, Capote’s play version whole thing retains the Capote flavor. out of print for almost two decades so it of The Grass Harp opened at the Mar- The original LP had to drop a song due was time to bring it back and I know that tin Beck Theatre on March 27, 1952, to time constraints, but it was restored would make him happy. Claibe passed in where it had a brief run of only thirty-six for the original CD release on Painted early 2003. His final song was written with performances. In the cast were Mildred Smiles. Then I reissued it on Varese me – I wanted to do a revue of my “What Natwick, Ruth Nelson, Jonathan Harris, Sarabande at the request of Claibe, who If” parodies and I couldn’t think of anyone Sterling Holloway, and Alice Pearce. -

Copyrighted Material

bindex.qxd 1/3/06 11:39 AM Page 285 Index NOTE: Page numbers in italics refer to illustrations and photos. Adler, Polly, 129 Backer, Evelyn (Evie) Weil, 75, 113, Adolfo, 188, 198–201, 203 151–154, 153, 162, 255 Aga Khan, Karim, 133, 170 Bailey, David, 181 Agnelli, Gianni, 69–72, 71, 133 Baker, Russell, 246 at ball, 139, 148, 233, 244–245 “Bal des Ardents, Le,” 107–108 cruises hosted by, 76–77, 97, 138 Baldwin, Billy, 226, 258 Agnelli, Marella, 34–35, 69–73, 71, balls 130 charity, 101–103, 180 at ball, 139, 148, 190, 239–240, hosted by Beistegui, 203, 244 244–245 hosted by Dunne, 66, 111, 112, 180 cruises hosted by, 76–77, 97, 138 masquerade (bal masqué), 107–110 Albee, Edward, 142 Mods and Rockers Ball, 103 Alexander, Shana, 99, 179 Paraguay ball plans, 255 Alsop, Susan Mary, 135, 215 See also Black and White Ball Amory, Cleveland, 110–111, 128–129 Bankhead, Tallulah, 28, 179 Answered Prayers (Capote), 51–52, 94, Barry, Bertha Eastmond, 126–128 101, 252–254 Barzini, Benedetta, 145, 232–233 Arvin, Newton, 26, 32, 36 Beaton, Cecil, 31, 38, 40, 41, 100, 120, Astor, Brooke Marshall, 44, 182, 193 243 Astor, Caroline, 109–110, 124 at ball, 139, 227 Astor, Carrie, 109–110 Capote’s letters to, 92, 114 Astor, Minnie. See Fosburgh, Minnie on Capote’s lifestyle, 76 Cushing AstorCOPYRIGHTEDMy FairMATERIAL Lady design by, 111, 156, 194 Astor, Vincent, 44 views on ball, 150 Avedon, Richard, 34, 132, 139, 181, “beautiful people” (“BP”), 165 203, 227, 258 Beistegui, Charles de, 203, 244 Bender, Marilyn, 118, 186 Baby Boomers, 118 Benton, Robert, 248–250 -

THE RURAL QUEER EXPERIENCE in TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICAN FICTION by Eric Hughes a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

THE RURAL QUEER EXPERIENCE IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICAN FICTION by Eric Hughes A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Middle Tennessee State University May 2021 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Will Brantley, Chair Dr. Allen Hibbard Dr. Mischa Renfroe ABSTRACT A common view of nonurban areas in the United States posits that rural communities and small towns are hegemonically heterosexual and gender conforming or inherently inhospitable to queer individuals. Queer studies have often reaffirmed these commonly held beliefs, as evident in a text such as David M. Halperin’s How to Be Gay (2012). With Kath Weston’s seminal “Get Thee to a Big City” (1995), a few commentators began to question this urban bias, or what J. Jack Halberstam labels “metronormativity.” Literary studies, however, have been late to take the “rural turn.” This dissertation thus examines the ways in which American writers from across the century and in diverse geographical areas have resisted queer urbanism through engagements with the urban/rural dichotomy. Chapter one focuses on Willa Cather and Sherwood Anderson, detailing Cather’s portrayal of queer cosmopolitanism and urbanity in short stories from The Troll Garden (1905), and pairing Cather’s A Lost Lady (1923) with Anderson’s Poor White (1920) to show how these writers challenged sexual norms in the modernizing Midwest. Chapter two examines Carson McCullers’s The Ballad of the Sad Café (1943) and The Member of the Wedding (1946) along with Truman Capote’s Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948) and The Grass Harp (1951), centering on representations of gender and sexual nonconformity in small southern towns. -

Europe in the Writings of Truman Capote Or the Steps to the Creation of the Nonfiction Novel

EUROPE IN THE WRITINGS OF TRUMAN CAPOTE OR THE STEPS TO THE CREATION OF THE NONFICTION NOVEL Emilio Cañadas Rodríguez Universidad Camilo José Cela Last 25th August 2004, we celebrated the 20th anniversary of the death of the American writer Truman Capote and simultaneously, in the following months, two milestones in his literary career: the fortieth anniversary of Truman Capote’s publication of the first lines of his masterpiece: In Cold Blood1 and the forty-fifth anniversary of the publication of Local Color, where the author gives a very personal and distinctive portrait of Europe; a kind of reportage of a post-war continent that now, years after, has just lived the expansion of the European Community last 1st of May. Due to the celebration of these events in the following months, it is the aim of this research to study the connexion between Truman Capote and Europe: his vision, his opinion, his writings, travels and, furthermore, the importance and the transcendent role of Europe as the root for the non-fiction novel in the making of In Cold Blood. Europe has always been a recurrent topic in the history of American Literature. As a starting point for our issue, we think first of Henry James, who sent his characters to Europe searching, looking for the land of experience, looking for the “tree of knowledge”, a place to learn and a place to be refilled with that experience and that knowledge2. We think of Washington Square and how Dr. Sloper believed 1 Although the book itself was published at the turn of the year 1965, the appearance of chapters or parts of the story in The New Yorker started after the summer of 1965.First chapter on the 25th September 1965. -

CHICK LIT and ITS CANONICAL FOREFATHERS: ANXIETIES ABOUT FEMALE SUBJECTIVITY in CONTEMPORARY WOMEN's FICTION by Laura Gronewol

Chick Lit and Its Canonical Forefathers: Anxieties About Female Subjectivity in Contemporary Women's Fiction Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Gronewold, Laura Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 10:31:52 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/238894 CHICK LIT AND ITS CANONICAL FOREFATHERS: ANXIETIES ABOUT FEMALE SUBJECTIVITY IN CONTEMPORARY WOMEN’S FICTION by Laura Gronewold ________________________________________ Copyright © Laura Gronewold 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2012 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Laura Gronewold entitled “Chick Lit and Its Canonical Forefathers: Anxieties about Female Subjectivity in Contemporary Women’s Fiction” and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _________________________________________________________ Date: 20 July 2012 Charles Scruggs _________________________________________________________ Date: 20 July 2012 Edgar A. Dryden _________________________________________________________ Date: 20 July 2012 Jennifer Jenkins Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

![Lucy Kroll Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3113/lucy-kroll-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-2283113.webp)

Lucy Kroll Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress

Lucy Kroll Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2002 Revised 2010 April Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms006016 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm82078576 Prepared by Donna Ellis with the assistance of Loren Bledsoe, Joseph K. Brooks, Joanna C. Dubus, Melinda K. Friend, Alys Glaze, Harry G. Heiss, Laura J. Kells, Sherralyn McCoy, Brian McGuire, John R. Monagle, Daniel Oleksiw, Kathryn M. Sukites, Lena H. Wiley, and Chanté R. Wilson Collection Summary Title: Lucy Kroll Papers Span Dates: 1908-1998 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1950-1990) ID No.: MSS78576 Creator: Kroll, Lucy Extent: 308,350 items ; 881 containers plus 15 oversize ; 356 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Literary and talent agent. Contracts, correspondence, financial records, notes, photographs, printed matter, and scripts relating to the Lucy Kroll Agency which managed the careers of numerous clients in the literary and entertainment fields. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Braithwaite, E. R. (Edward Ricardo) Davis, Ossie. Dee, Ruby. Donehue, Vincent J., -1966. Fields, Dorothy, 1905-1974. Foote, Horton. Gish, Lillian, 1893-1993. Glass, Joanna M. Graham, Martha. Hagen, Uta, 1919-2004. -

TELLING the TRUTH: CREATIVE NONFICTION in CAPOTE's in COLD BLOOD & MAILER's the EXECUTIONER's SONG by James R. Capp A

TELLING THE TRUTH: CREATIVE NONFICTION IN CAPOTE’S IN COLD BLOOD & MAILER’S THE EXECUTIONER’S SONG by James R. Capp A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Wilkes Honors College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Arts and Sciences with a Concentration in English Literature Wilkes Honors College of Florida Atlantic University Jupiter, Florida May 2008 TELLING THE TRUTH: CREATIVE NONFICTION IN CAPOTE’S IN COLD BLOOD & MAILER’S THE EXECUTIONER’S SONG by James R. Capp This thesis was prepared under the direction of the candidate’s thesis advisor, Dr. Laura Barrett, and has been approved by the members of her/his supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of The Honors College and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Arts and Sciences. SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ____________________________ Dr. Laura Barrett ____________________________ Prof. James McGarrah ______________________________ Dean, Wilkes Honors College ____________ Date ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Obviously, I need to express my gratitude to Dr. Laura Barrett for her tremendous display of advising skills and for her infinite patience. Additionally, I wish to thank certain persons whose contributions to my work were of great importance: Professor Jim McGarrah, who jumped into this project with great enthusiasm; Mr. Peter Salomone, whose encouraging words and constructive criticism were essential to the completion of this thesis; the lovely Ms. Cara Piccirillo, who stood by me through it all; and finally, all of my professors, friends and family. You were all wonderful for supporting me throughout the years, and you were all especially kind during the home stretch of this project when I broke my right hand.