'H*E E M P O R I a Earch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alabama Literary Review 2011

Alabama Literary Review 2011 volume 20 number 1 TROY UNIVERSITY Alabama Literary Review Editor William Thompson Fiction Editors Jim Davis Theron Montgomery Poetry Editor Patricia Waters Webmaster Ben Robertson Cover Design Heather Turner Alabama Literary Review is a state literary medium representing local and national submissions, supported by Troy University and Troy University Foundation. Published once a year, Alabama Literary Review is a free service to all Alabama libraries and all Alabama two- and four-year insti- tutions of higher learning. Subscription rates are $10 per year, $5 for back copies. Rates are subject to change without notice. Alabama Literary Review publishes fiction, poetry, and essays. Pays in copies. Pays honorarium when available. First Serial Rights returned to author upon publication. Manuscripts and editorial or business correspon- dence should be addressed to Alabama Literary Review, 254 Smith Hall, Troy University, Troy, Alabama 36082. Submissions will not be returned nor queries answered unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. Please allow two or three months for our response. 2010 Alabama Literary Review. All rights reserved. ISSN 0890-1554. Alabama Literary Review is indexed in The American Humanities Index and The Index of American Periodic Verse. CONTENTS Daniel Tobin from From Nothing . .1 April Lindner Seen From Space . .6 Robert B. Shaw Back Home . .8 Loren Graham Country Boy . .18 Octobers . .19 Letters . .20 Zakia Khwaja Nastaliq . .21 Robert B. Shaw Dinosaur Tracks . .22 “Pity the Monsters!” . .23 Stephen Cushman The Red List . .25 Enrique Barrero Rodríguez / John Poch Hoy quisiera, por fin, sobre el desbrozo . .55 Today I wanted, finally, beyond the removal . -

Truman Capote's Early Short Stories Or the Fight of a Writer to Find His

Truman Capote’s Early Short Stories or The Fight of a Writer to Find His Own Voice Emilio Cañadas Rodríguez Universidad Alfonso X El Sabio (Madrid) Abstract Truman Capote’s early stories have not been studied in depth so far and literary studies on Truman Capote’s short stories start with his first collection “A Tree of Night and Other Stories”, published in 1949. Stories previous to 1945 such as “The Walls Are Cold”, “A Mink’s of One’s Own” or “The Shape of things” are basically to be discovered and their relevance lie on the fact of being successful narrative exercises that focus more in the construction of characters than in the action itself. They are stories to be read “on one sitting” and stories that make the reader foresee Capote’s skilful short narrative in the future. It is our aim, then, in this paper to present the first three ever written stories by Truman Capote, to analyse them and to remark their relevance for Capote’s literary universe. Dwarfed and darkened by narrative masterpieces such as In Cold Blood (1965) or Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948) , Truman Capote’s short stories have never been as acclaimed or studied as his novels. Literary critics have predominantly focussed their criticism on Capote’s work as a novelist emphasizing on the “Gothicism” and “the form of horror” in Other Voices, Other Rooms or the author’s innovative techniques in In Cold Blood.1 However, apart from the complete research of Kenneth T. Reed, there are several studies on Capote’s whole literary career like William Nance’s or Helen S. -

1 Breakfast at Tiffany's Truman Capote, 1958 I Am Always Drawn Back To

1 Breakfast at Tiffany's surrounded by photographs of ice-hockey stars, there is always a large bowl of fresh Truman Capote, 1958 flowers that Joe Bell himself arranges with matronly care. That is what he was doing when I came in. I am always drawn back to places where I have lived, the houses and their "Naturally," he said, rooting a gladiola deep into the bowl, "naturally I wouldn't have neighborhoods. For instance, there is a brownstone in the East Seventies where, got you over here if it wasn't I wanted your opinion. It's peculiar. A very peculiar thing during the early years of the war, I had my first New York apartment. It was one room has happened." crowded with attic furniture, a sofa and fat chairs upholstered in that itchy, particular red "You heard from Holly?" velvet that one associates with hot days on a tram. The walls were stucco, and a color He fingered a leaf, as though uncertain of how to answer. A small man with a fine rather like tobacco-spit. Everywhere, in the bathroom too, there were prints of Roman head of coarse white hair, he has a bony, sloping face better suited to someone far ruins freckled brown with age. The single window looked out on a fire escape. Even so, taller; his complexion seems permanently sunburned: now it grew even redder. "I can't my spirits heightened whenever I felt in my pocket the key to this apartment; with all its say exactly heard from her. I mean, I don't know. -

Annie Hall: Screenplay Pdf, Epub, Ebook

ANNIE HALL: SCREENPLAY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Woody Allen,Marshall Brickman | 128 pages | 21 Feb 2000 | FABER & FABER | 9780571202140 | English | London, United Kingdom Annie Hall: Screenplay PDF Book Photo Gallery. And I thought of that old joke, you know. Archived from the original on January 20, Director Library of Congress, Washington, D. According to Brickman, this draft centered on a man in his forties, someone whose life consisted "of several strands. Vanity Fair. Retrieved January 29, The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 10, All the accolades and praise encouraged me to pick up this script. Archived from the original on December 30, Rotten Tomatoes. And I'm amazed at how epic the characters can be even when nothing blockbuster-ish happens. Annie and Alvy, in a line for The Sorrow and the Pity , overhear another man deriding the work of Federico Fellini and Marshall McLuhan ; Alvy imagines McLuhan himself stepping in at his invitation to criticize the man's comprehension. Retrieved March 23, How we actually wrote the script is a matter of some conjecture, even to one who was intimately involved in its preparation. It was fine, but didn't live up to the hype, although that may be the hype's fault more than the script's. And I thought, we have to use this. It was a delicious and crunchy treat for its realistic take on modern-day relationships and of course, the adorable neurotic-paranoid Alvy. The Paris Review. Even in a popular art form like film, in the U. That was not what I cared about Woody Allen and the women in his work. -

![Truman Capote Papers [Finding Aid]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6079/truman-capote-papers-finding-aid-706079.webp)

Truman Capote Papers [Finding Aid]

Truman Capote Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2011 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms011026 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm81047043 Prepared by Manuscript Division Staff Collection Summary Title: Truman Capote Papers Span Dates: 1947-1965 ID No.: MSS47043 Creator: Capote, Truman, 1924-1984 Extent: 70 items ; 8 containers ; 3.2 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Author and dramatist. Chiefly literary manuscripts, including notebooks, journals, drafts, and manuscripts of prose fiction, dramas and screenplays, and other writings. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Brando, Marlon. Capote, Truman, 1924-1984. Capote, Truman, 1924-1984. Breakfast at Tiffany's; a short novel and three stories. 1958. Capote, Truman, 1924-1984. In cold blood : a true account of a multiple murder and its consequences. 1965. Capote, Truman, 1924-1984. Other voices, other rooms. 1948. Subjects American fiction. American literature. Drama. Fiction. Literature. Motion picture plays. Musicals. Short stories. Occupations Authors. Dramatists. Administrative Information Provenance The papers of Truman Capote, author and dramatist, were given to the Library of Congress by Capote in 1967-1969. Processing History The papers of Truman Capote were arranged and described in 1968 and 1997. -

To Download the PDF File

Vi • 1n• tudents like CS; • SIC, pool, city / By Gloria Pena rate, gymnastics, volleyball, , Have you noticed five new stu- r pingpong, stamp collecting, mo I '• dents roamang the halls within del airplane, playing the flute B the last three weeks? Well, they and guitar, and all seemed to be were not here permanently, but enthusiastic about girls were exchange students from Guatemala, Central America, The school here is different vasatang Shreveport, The Louisi from those in Guatemala in the ana Jaycees sponsored these way that here the students go to students and the people they are the classes, where as in Guate staying with will in turn visit mala, the teachers change class Guatamala and stay with a famaly rooms. One sa ad that ·'here the there. students are for the teachers, Whale visitang Shreveport they where there, the teachers are for -did such !hangs as visit a farm in the students." Three of the stu ~aptain ~'trrur 11igtp ..ctpool Texas, where they had a wiener dents are still in high school, roast ; visit Barksdale A ir Force while the other two are in col Base· take an excursion to lege, one studying Architecture Shreve Square, go to parties; and the other studying Business Volume IX Shreveport, La., December 15, 1975 Number 5 take in sO'me skating; and one Administration. even had the experaence of going flying with Mrs. Helen Wray. The students also went shop ping at Southpark Mall of which Christmas brings gifts; they were totally amazed, and at Eastgate Shopping Center by Captain Shreve. One even catalogue offers I aug hs splurged and bought $30 worth By Sandra Braswell $2,250,000. -

Review of Capote's in Cold Blood

Themis: Research Journal of Justice Studies and Forensic Science Volume 1 Themis: Research Journal of Justice Studies and Forensic Science, Volume I, Spring Article 1 2013 5-2013 Review of Capote’s In Cold Blood Yevgeniy Mayba San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/themis Part of the American Literature Commons, Criminal Law Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Mayba, Yevgeniy (2013) "Review of Capote’s In Cold Blood," Themis: Research Journal of Justice Studies and Forensic Science: Vol. 1 , Article 1. https://doi.org/10.31979/THEMIS.2013.0101 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/themis/vol1/iss1/1 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Justice Studies at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Themis: Research Journal of Justice Studies and Forensic Science by an authorized editor of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Review of Capote’s In Cold Blood Keywords Truman Capote, In Cold Blood, book review This book review is available in Themis: Research Journal of Justice Studies and Forensic Science: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/themis/vol1/iss1/1 Mayba: In Cold Blood Review 1 Review of Capote’s In Cold Blood Yevgeniy Mayba Masterfully combining fiction and journalism, Truman Capote delivers a riveting account of the senseless mass murder that occurred on November 15, 1959 in the quiet rural town of Holcomb, Kansas. Refusing to accept the inherent lack of suspense in his work, Capote builds the tension with the brilliant use of imagery and detailed exploration of the characters. -

Other Voices, Other Rooms Came to Him in the Form of a Revelation During a Walk in the Woods

Table of Contents Title Page Dedication Epigraph INTRODUCTION PART ONE ONE TWO THREE FOUR FIVE PART TWO SIX SEVEN EIGHT NINE TEN ELEVEN PART THREE TWELVE About the Author Copyright Page FOR NEWTON ARVIN The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked. Who can know it? JEREMIAH 17:9 INTRODUCTION John Berendt As Truman Capote remembered it years later, the idea for Other Voices, Other Rooms came to him in the form of a revelation during a walk in the woods. He was twenty-one, living with relatives in rural Alabama, and working on a novel that he had begun to fear was “thin, clever, unfelt.” One afternoon, he went for a stroll along the banks of a stream far from home, pondering what to do about it, when he came upon an abandoned mill that brought back memories from his early childhood. The remembered images sent his mind reeling, causing him to slip into a “creative coma” during which a completely different book presented itself and began to take shape, virtually in its entirety. Reaching home after dark, he skipped supper, put the manuscript of the troublesome unfinished novel into a bottom bureau drawer (it was entitled “Summer Crossing,” never published, later lost), climbed into bed with a handful of pencils and a pad of paper, and wrote: “Other Voices, Other Rooms—a novel by Truman Capote. Now a traveler must make his way to Noon City by the best means he can . .”1 Whether or not Capote’s remarkable first novel came to him as he said it did, in a spontaneous flow of words as if dictated by “a voice from a cloud,” the work that emerged two years later was as lyrical and rich in poetic imagery as if it had been written by a writer possessed. -

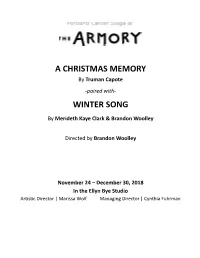

A Christmas Memory Winter Song

A CHRISTMAS MEMORY By Truman Capote -paired with- WINTER SONG By Merideth Kaye Clark & Brandon Woolley Directed by Brandon Woolley November 24 – December 30, 2018 In the Ellyn Bye Studio Artistic Director | Marissa Wolf Managing Director | Cynthia Fuhrman Music Director Scenic Designer Costume Designer Mont Chris Daniel Meeker Paula Buchert Hubbard Lighting Designer Sound Designer Stage Manager Sarah Hughey Casi Pacilio Janine Vanderhoff Production Assistant Alexis Ellis-Alvarez Featuring Merideth Kaye Clark & Leif Norby Accompanied by Mont Chris Hubbard Original Underscore Music by Mont Chris Hubbard Arrangements by Merideth Kaye Clark & Mont Chris Hubbard Performed without intermission. Videotaping or other photo or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. If you photograph the set before or after the performance, please credit the designers if you share the image. The Actors and Stage Managers employed in this production are members of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. Season Superstars: Tim & Mary Boyle Umpqua Bank LCC Supporting Season Sponsors: RACC Oregon Arts Commission The Wallace Foundation Artslandia Arts Tax Show Sponsors: The Shubert Foundation NW Natural Delta Air Lines Dr. Barbara Hort Studio Sponsor: Mary & Don Blair What She Said Sponsors A Celebration of Women Playwrights Ronni Lacroute Brigid Flanigan Diana Gerding Mary Boyle FROM ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MARISSA WOLF Welcome to the holiday season at Portland Center Stage at The Armory! It’s drizzly outside, but warm and bright inside our theater. We hope you’ll enjoy grabbing a hot drink and cozying up with us for these spirited, playful holiday shows. -

Driving Truman Capote: a Memoir

Theron Montgomery Driving Truman Capote: A Memoir On a calm, cool April afternoon in 1975, I received an unexpected call from my father on the residence First Floor pay phone in New Men’s Dorm at Birmingham-Southern College. My father’s voice came over the line, loud and enthused. “Hi,” he said, enjoying his surprise. He asked me how I was doing, how school was. “Now, are you listen- ing?” he said. “I’ve got some news.” Truman Capote, the famous writer of In Cold Blood, would be in our hometown of Jacksonville, Alabama, the next day to speak and read and visit on the Jacksonville State University campus, where my father was Vice-President for Academic Affairs. It was a sudden arrangement Capote’s agent had negotiated a few days before with the school, pri- marily at my father’s insistence, to follow the author’s read- ing performance at the Von Braun Center, the newly dedicat- ed arts center, in Huntsville. Jacksonville State University had agreed to Capote’s price and terms. He and a traveling companion would be driven from Huntsville to the campus by the SGA President early the next morning and they would be given rooms and breakfast at the university’s International House. Afterwards, Capote would hold a luncheon reception with faculty at the library, and in the afternoon, he would give a reading performance at the coliseum. My father and I loved literature, especially southern liter- ature, and my father knew I had aspirations of becoming a writer, too. “You must come and hear him,” he said over the phone, matter-of-fact and encouraging. -

La Unidad Literaria En La Obra De Trumañ Capote

ELENA ORTELLS MONTÓN FICCIÓN Y NO-FICCIÓN: LA UNIDAD LITERARIA EN LA OBRA DE TRUMAÑ CAPOTE Anejo n.° XXXII de la Revista CUADERNOS DE FILOLOGÍA DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOLOGÍA INGLESA Y ALEMANA (Literatura norteamericana) FACULTAT DE FILOLOGÍA UNIVERSITAT DE VALENCIA ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN 1 CAPÍTULO 1. LA UNIDAD DE TEMAS EN LA OBRA LITERARIA DE TRUMAN CAPOTE 14 1.1. La teoría literaria de Truman Capote: el conflicto entre ficción y no-ficción 15 X 1.2. Las "dark short stories" 22 1.2.1. "Miriam" y "A Tree of Night" 24 1.2.2. "The Headless Hawk" y "Shut a Final Door" 26 1.2.3. "Master Misery" 31 1.3. Las "daylight stories" 33 1.3.1. "My Side of the Matter" 34 1.3.2. "Jug of Sil ver" y "Children on Their Birthdays" 35 1.4. Other Voices, Other Rooms 38 1.5. "A Diamond Guitar" 46 1.6. Local Color 47 1.7. The Grass Harp 51 1.8. "House of Flowers" 57 1.9. Evocaciones autobiográficas: "A Christmas Memory", The Thanksgiving Visitor, "Dazzle" y One Christmas 58 1.10. The Muses Are Heard 63 1.11. "The Duke in His Domain" 66 1.12. Observations 71 1.13. Breakfast at Tiffany's 71 1.14. "Among the Paths to Edén" 75 1.15. In Cold Blood 76 * 1.16. Music for Chamaleons 84 1.17. Answered Prayers 92 CAPÍTULO 2. LA MIRADA DEL NARRADOR 2.1. La problemática identificación autor/narrador 95 ,A 2.2. Hacia una clasificación de la figura del narrador 97 >0 2.2.1. -

February 10, 2009 (XVIII:5) Jack Clayton the INNOCENTS (1961, 100 Min)

February 10, 2009 (XVIII:5) Jack Clayton THE INNOCENTS (1961, 100 min) Directed and produced by Jack Clayton Based on the novella “The Turn of the Screw” by Henry James Screenplay by William Archibald and Truman Capote Additional scenes and dialogue by John Mortimer Original Music by Georges Auric Cinematography by Freddie Francis Film Editing by Jim Clark Art Direction by Wilfred Shingleton Deborah Kerr...Miss Giddens Peter Wyngarde...Peter Quint Megs Jenkins...Mrs. Grose Michael Redgrave...The Uncle Martin Stephens...Miles Pamela Franklin...Flora Clytie Jessop...Miss Jessel Isla Cameron...Anna JACK CLAYTON (March 1, 1921, Brighton, East Sussex, England, UK—February 26, 1995, Slough, Berkshire, England, UK) had 10 writing credits, some of which are In Cold Blood (1996), Other directing credits: Memento Mori (1992), The Lonely Passion of Voices, Other Rooms (1995), The Grass Harp (1995), One Judith Hearne (1987), Something Wicked This Way Comes Christmas (1994), The Glass House (1972), Laura (1968), In Cold (1983), The Great Gatsby (1974), Our Mother's House (1967), Blood (1967), The Innocents (1961), Breakfast at Tiffany's (1961), The Pumpkin Eater (1964), The Innocents (1961), Room at the Beat the Devil (1953), and Stazione Termini/Indiscretion of an Top (1959), The Bespoke Overcoat (1956), Naples Is a Battlefield American Wife (1953). (1944). DEBORAH KERR (September 30, 1921, Helensburgh, Scotland, JOHN MORTIMER (April 21, 1923, Hampstead, London, England, UK—October 16, 2007, Suffolk, England, UK) has 53 Acting UK—January 16, 2009, Oxfordshire, England, UK) has 59 Credits. She won an Honorary Oscar in 1994. Before that she had writing credits, some of which are In Love and War (2001), Don six best actress nominations: The Sundowners 1959, Separate Quixote (2000), Tea with Mussolini (1999), Cider with Rosie Tables (1958), Heaven Knows, Mr.