Buccopharyngeal Membrane: Report of a Case and Review of the Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3 Embryology and Development

BIOL 6505 − INTRODUCTION TO FETAL MEDICINE 3. EMBRYOLOGY AND DEVELOPMENT Arlet G. Kurkchubasche, M.D. INTRODUCTION Embryology – the field of study that pertains to the developing organism/human Basic embryology –usually taught in the chronologic sequence of events. These events are the basis for understanding the congenital anomalies that we encounter in the fetus, and help explain the relationships to other organ system concerns. Below is a synopsis of some of the critical steps in embryogenesis from the anatomic rather than molecular basis. These concepts will be more intuitive and evident in conjunction with diagrams and animated sequences. This text is a synopsis of material provided in Langman’s Medical Embryology, 9th ed. First week – ovulation to fertilization to implantation Fertilization restores 1) the diploid number of chromosomes, 2) determines the chromosomal sex and 3) initiates cleavage. Cleavage of the fertilized ovum results in mitotic divisions generating blastomeres that form a 16-cell morula. The dense morula develops a central cavity and now forms the blastocyst, which restructures into 2 components. The inner cell mass forms the embryoblast and outer cell mass the trophoblast. Consequences for fetal management: Variances in cleavage, i.e. splitting of the zygote at various stages/locations - leads to monozygotic twinning with various relationships of the fetal membranes. Cleavage at later weeks will lead to conjoined twinning. Second week: the week of twos – marked by bilaminar germ disc formation. Commences with blastocyst partially embedded in endometrial stroma Trophoblast forms – 1) cytotrophoblast – mitotic cells that coalesce to form 2) syncytiotrophoblast – erodes into maternal tissues, forms lacunae which are critical to development of the uteroplacental circulation. -

Vocabulario De Morfoloxía, Anatomía E Citoloxía Veterinaria

Vocabulario de Morfoloxía, anatomía e citoloxía veterinaria (galego-español-inglés) Servizo de Normalización Lingüística Universidade de Santiago de Compostela COLECCIÓN VOCABULARIOS TEMÁTICOS N.º 4 SERVIZO DE NORMALIZACIÓN LINGÜÍSTICA Vocabulario de Morfoloxía, anatomía e citoloxía veterinaria (galego-español-inglés) 2008 UNIVERSIDADE DE SANTIAGO DE COMPOSTELA VOCABULARIO de morfoloxía, anatomía e citoloxía veterinaria : (galego-español- inglés) / coordinador Xusto A. Rodríguez Río, Servizo de Normalización Lingüística ; autores Matilde Lombardero Fernández ... [et al.]. – Santiago de Compostela : Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Servizo de Publicacións e Intercambio Científico, 2008. – 369 p. ; 21 cm. – (Vocabularios temáticos ; 4). - D.L. C 2458-2008. – ISBN 978-84-9887-018-3 1.Medicina �������������������������������������������������������������������������veterinaria-Diccionarios�������������������������������������������������. 2.Galego (Lingua)-Glosarios, vocabularios, etc. políglotas. I.Lombardero Fernández, Matilde. II.Rodríguez Rio, Xusto A. coord. III. Universidade de Santiago de Compostela. Servizo de Normalización Lingüística, coord. IV.Universidade de Santiago de Compostela. Servizo de Publicacións e Intercambio Científico, ed. V.Serie. 591.4(038)=699=60=20 Coordinador Xusto A. Rodríguez Río (Área de Terminoloxía. Servizo de Normalización Lingüística. Universidade de Santiago de Compostela) Autoras/res Matilde Lombardero Fernández (doutora en Veterinaria e profesora do Departamento de Anatomía e Produción Animal. -

BGD B Lecture Notes Docx

BGD B Lecture notes Lecture 1: GIT Development Mark Hill Trilaminar contributions • Overview: o A simple tube is converted into a complex muscular, glandular and duct network that is associated with many organs • Contributions: o Endoderm – epithelium of the tract, glands, organs such as the liver/pancreas/lungs o Mesoderm (splanchnic) – muscular wall, connective tissue o Ectoderm (neural crest – muscular wall neural plexus Gastrulation • Process of cell migration from the epiblast through the primitive streak o Primitive streak forms on the bilaminar disk o Primitive streak contains the primitive groove, the primitive pit and the primitive node o Primitive streak defines the body axis, the rostral caudal ends, and left and right sides Thus forms the trilaminar embryo – ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm • Germ cell layers: o ectoderm – forms the nervous system and the epidermis epithelia 2 main parts • midline neural plate – columnar epithelium • lateral surface ectoderm – cuboidal, containing sensory placodes and skin/hair/glands/enamel/anterior pituitary epidermis o mesoderm – forms the muscle, skeleton, and connective tissue cells migrate second migrate laterally, caudally, rostrally until week 4 o endoderm – forms the gastrointestinal tract epithelia, the respiratory tract and the endocrine system cells migrate first and overtake the hypoblast layer line the primary yolk sac to form the secondary yolk sac • Membranes: o Rostrocaudal axis Ectoderm and endoderm form ends of the gut tube, no mesoderm At each end, form the buccopharyngeal -

Trávicí Systém

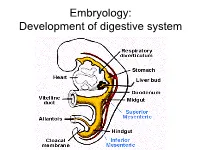

Embryology: Development of digestive system Embryo folding – incorporation of endoderm to form primitive gut. Outside of embryo – yolk sac and allantois. Vitelline duct Stomodeum (primitive mouth) the oral cavity + the salivary glands Proctodeum primitive anal pit Primitive gut whole digestive tube + accessory glands pharynx forgut midgut hindgut • The epithelium and glandular cells of associated glands of the gastrointestinal tract develop from endoderm • The connective tissue, muscle tissue and mesothelium are derived from splanchnic mesoderm • The enteric nervous system develops from neural crest primitive gut foregut midgut hindgut pharyngeal above ductus cloacal membrane omphalomesentericus membrane and yolk sack Derivatives of forgut – pharynx, esophagus (+ respiratory diverticul), stomach, cranial part of duodenum midgut – caudal part of duodenum (+ liver, gall bladder, pancreas), small intestine and part of large intestine (to the flexura coli sin.) hindgut – large intestine (from flexura coli sin.), rectum, upper part of anal canal Oral cavity • primitive mouth pit – stomodeum • lined with ectoderm • surrounded by: - processus frontalis (single) - proc. maxillares (paired) - proc. mandibulares (paired) • pharyngeal membrane (it ruptures during the 4th week, primitive gut communicates with amnionic cavity Pharyngeal (branchial) apparatus Pharyngeal arches • appear in weeks 4 - 5 • on the ventral side of the pharyngeal gut. • each arch has cartilage, cranial nerve, aortic arch artery and muscle • pharyngeal clefts and pouches -

Embryology and Teratology in the Curricula of Healthcare Courses

ANATOMICAL EDUCATION Eur. J. Anat. 21 (1): 77-91 (2017) Embryology and Teratology in the Curricula of Healthcare Courses Bernard J. Moxham 1, Hana Brichova 2, Elpida Emmanouil-Nikoloussi 3, Andy R.M. Chirculescu 4 1Cardiff School of Biosciences, Cardiff University, Museum Avenue, Cardiff CF10 3AX, Wales, United Kingdom and Department of Anatomy, St. George’s University, St George, Grenada, 2First Faculty of Medicine, Institute of Histology and Embryology, Charles University Prague, Albertov 4, 128 01 Prague 2, Czech Republic and Second Medical Facul- ty, Institute of Histology and Embryology, Charles University Prague, V Úvalu 84, 150 00 Prague 5 , Czech Republic, 3The School of Medicine, European University Cyprus, 6 Diogenous str, 2404 Engomi, P.O.Box 22006, 1516 Nicosia, Cyprus , 4Department of Morphological Sciences, Division of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, C. Davila University, Bucharest, Romania SUMMARY Key words: Anatomy – Embryology – Education – Syllabus – Medical – Dental – Healthcare Significant changes are occurring worldwide in courses for healthcare studies, including medicine INTRODUCTION and dentistry. Critical evaluation of the place, tim- ing, and content of components that can be collec- Embryology is a sub-discipline of developmental tively grouped as the anatomical sciences has biology that relates to life before birth. Teratology however yet to be adequately undertaken. Surveys (τέρατος (teratos) meaning ‘monster’ or ‘marvel’) of teaching hours for embryology in US and UK relates to abnormal development and congenital medical courses clearly demonstrate that a dra- abnormalities (i.e. morphofunctional impairments). matic decline in the importance of the subject is in Embryological studies are concerned essentially progress, in terms of both a decrease in the num- with the laws and mechanisms associated with ber of hours allocated within the medical course normal development (ontogenesis) from the stage and in relation to changes in pedagogic methodol- of the ovum until parturition and the end of intra- ogies. -

Índice De Denominacións Españolas

VOCABULARIO Índice de denominacións españolas 255 VOCABULARIO 256 VOCABULARIO agente tensioactivo pulmonar, 2441 A agranulocito, 32 abaxial, 3 agujero aórtico, 1317 abertura pupilar, 6 agujero de la vena cava, 1178 abierto de atrás, 4 agujero dental inferior, 1179 abierto de delante, 5 agujero magno, 1182 ablación, 1717 agujero mandibular, 1179 abomaso, 7 agujero mentoniano, 1180 acetábulo, 10 agujero obturado, 1181 ácido biliar, 11 agujero occipital, 1182 ácido desoxirribonucleico, 12 agujero oval, 1183 ácido desoxirribonucleico agujero sacro, 1184 nucleosómico, 28 agujero vertebral, 1185 ácido nucleico, 13 aire, 1560 ácido ribonucleico, 14 ala, 1 ácido ribonucleico mensajero, 167 ala de la nariz, 2 ácido ribonucleico ribosómico, 168 alantoamnios, 33 acino hepático, 15 alantoides, 34 acorne, 16 albardado, 35 acostarse, 850 albugínea, 2574 acromático, 17 aldosterona, 36 acromatina, 18 almohadilla, 38 acromion, 19 almohadilla carpiana, 39 acrosoma, 20 almohadilla córnea, 40 ACTH, 1335 almohadilla dental, 41 actina, 21 almohadilla dentaria, 41 actina F, 22 almohadilla digital, 42 actina G, 23 almohadilla metacarpiana, 43 actitud, 24 almohadilla metatarsiana, 44 acueducto cerebral, 25 almohadilla tarsiana, 45 acueducto de Silvio, 25 alocórtex, 46 acueducto mesencefálico, 25 alto de cola, 2260 adamantoblasto, 59 altura a la punta de la espalda, 56 adenohipófisis, 26 altura anterior de la espalda, 56 ADH, 1336 altura del esternón, 47 adipocito, 27 altura del pecho, 48 ADN, 12 altura del tórax, 48 ADN nucleosómico, 28 alunarado, 49 ADNn, 28 -

Ectodermal Pharyngeal Clefts

Embryology: Development of digestive system Flecture of embryo – incorporation of endoderm to form primitive gut. Outside of embryo – yolk sac and allantois. Vitelline duct Stomodeum (primitive mouth) the oral cavity + the salivary glands Proctodeum primitive anal pit Primitive gut whole digestive tube + accessory glands orofacial membrane Tracheo- esophageal septum Proctodeum cloacal membrane Primitive gut pharynx forgut midgut hindgut Derivatives of foregut – pharynx, (+ respiratory diverticle),esophagus, stomach, cranial part of duodenum, (+ liver, gall bladder pancreas) midgut – caudal part of duodenum, small intestine and part of large intestine (1/3 of colon transv.) hindgut – the rest of large intestine, rectum, upper part of the anal canal Tissues in GIT • The epithelium of gut and glandular cells of associated glands of the gastrointestinal tract develop from endoderm • The connective tissue, muscle tissue and mesothelium derive from splanchnic mesoderm • The enteric nervous system develops from neural crest primitive gut foregut midgut hindgut from above ductus to cloacal pharyngeal omphalomesentericus membrane membrane and yolk sack Pharyngeal membrane liver, bile duct, pancreas Rectum Origin: forgut, midgut. hindgut Oral cavity • primitive mouth pit – stomodeum • lined with ectoderm • surrounded by: - processus frontalis (single) - proc. maxillares (paired) - proc. mandibulares (paired) • orophacial membrane (it ruptures during the 4th week, primitive gut communicates with amnionic cavity) Pharyngeal (branchial) apparatus -

Facial and Palatal Development

11. FACIAL AND PALATAL DEVELOPMENT Letty Moss-Salentijn DDS, PhD Dr. Edwin S.Robinson Professor of Dentistry (in Anatomy and Cell Biology) E-mail: [email protected] READING ASSIGNMENT: Larsen 3rd edition: p.352; pp.365-371; 398-404. SUMMARY: The external human face develops between the 4th and 6th weeks of embryonic development. Facial swellings arise on the frontonasal process (2 medial nasal and 2 lateral nasal processes) and the first pharyngeal arch (2 mandibular and 2 maxillary processes). By a process of merging and some localized fusion these processes come together to form the continuous surfaces of the external face. The primary palate is formed in this period by fusion/merging of the medial nasal and maxillary processes. Subsequently, between 6th and 12th embryonic/fetal weeks, the secondary palate is formed as the result of fusion between palatal processes growing from the oral surfaces of the maxillary processes. Each merging and fusion site is also the site of a potential facial or palatal cleft. LEARNING OBJECTIVES You should be able to: a. Demonstrate on a frontal image of a human face those parts of the face that are formed by contributions from the frontonasal process and those that are formed by contributions from the first pharyngeal arch. b. Describe the following as to site, composition, time of appearance, and fate: oropharyngeal membrane, oronasal membrane. c. List the derivatives of the four pairs of facial processes and the pair of palatal processes. d. Describe the development of the nose and primary palate. e. Explain the differences between the processes of merging and fusion. -

Pharyngeal Arches

9. PHARYNGEAL ARCHES Letty Moss-Salentijn DDS, PhD Dr. Edwin S. Robinson Professor of Dentistry (in Anatomy and Cell Biology) E-mail: [email protected] READING ASSIGNMENT: Larsen 3rd Edition. Chapter 12: pp. 352; 358-365; 405-412 SUMMARY: The phylogenetic significance of pharyngeal arches is discussed briefly, followed by a description of the ontogenetic development of these structures. Five pair of pharyngeal arches are transiently present in the period of 20-35 days of embryonic development. The significant role of the cephalic neural crest for the development of the facial region and the visceral neck is stressed. There is a spatial and developmental relationship between the rhombomeres of the hindbrain and the pharyngeal arches, which is controlled by a Hox code. The components of each pharyngeal arch include an aortic arch, a specific cranial nerve and associated muscle, and a cartilage skeleton. The adult derivatives of each of these components are reviewed. LEARNING OBJECTIVES: You should be able to: a. List the developmental stages and the rostrocaudal sequence in which the pharyngeal arches are visible externally in the human embryo. b. List the evolutionary changes (including the acquisition of the pharyngeal arches) from simple chordates to early vertebrates. c. Describe pharyngeal arches, pharyngeal pouches, pharyngeal grooves, pharyngeal membranes, and pharyngeal clefts. d. Describe somitomeres. List their number in the cephalic region, and describe their contribution to the pharyngeal arch derivatives. e. Describe the migration, and final distribution of midbrain and hindbrain neural crest in the head, neck and heart regions. f. Describe the boundary between cephalic neural crest and trunk neural crest, and explain the significance of this distinction for the neural crest derivatives. -

Endodermal Derivatives, Formation of the Gut and Its Subsequent Rotation

18. ENDODERMAL DERIVATIVES, FORMATION OF THE GUT AND ITS SUBSEQUENT ROTATION Dr. Mike Gershon Department of Anatomy & Cell Biology Telephone: 305-3447 E-mail: [email protected] READING ASSIGNMENT: Larsen 3rd edition: Review Chapter 6: pp. 134—149; Chapter 9, pp. 235-259. SUMMARY:The gut is formed as a critical byproduct of the folding of the germ disc. The primitive bowel extends from the buccopharyngeal membrane to the cloacal membrane. It is portioned into a foregut, a midgut, and a hindgut. The foregut, which gives rise to the largest number of structures forms the pharynx and its derivatives, the lower respiratory tract, the esophagus, the stomach, the duodenum, proximal to the ampulla of Vater, the liver, the pancreas, and the biliary apparatus. From the stomach on, these structures are supplied by the celiac artery. The midgut is supplied by the superior mesenteric artery, and the hindgut is supplied by the inferior mesenteric artery. These vessels define the segmentation of the bowel. The stomach rotates 90° clockwise as it grows, which has major consequences for the positioning of the mesenteries, the duodenum, bile duct, and pancreas. The liver and biliary system arise from the hepatic diverticulum, which grows into the ventral mesentery and septum transversum. The hepatic diverticulum divides into a cranial and a caudal division: the cranial forms the liver and the smaller, caudal forms the extrahepatic biliary system. The pancreas arises from dorsal and ventral pancreatic buds. The rotation of the stomach brings the buds together so that they can fuse into a definitive pancreas. The midgut grows rapidly and herniates into the umbilical cord, where it rotates 90° counterclockwise. -

Hedgehog Activity Controls Opening of the Primary Mouth

Developmental Biology ∎ (∎∎∎∎) ∎∎∎–∎∎∎ Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Developmental Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/developmentalbiology Hedgehog activity controls opening of the primary mouth Jacqueline M. Tabler a,b, Trióna G. Bolger a, John Wallingford b,c, Karen J. Liu a,n a Department of Craniofacial Development and Stem Cell Biology, King's College London, UK b Department of Molecular Biosciences, University of Texas at Austin, USA c Howard Hughes Medical Institute, USA article info abstract Article history: To feed or breathe, the oral opening must connect with the gut. The foregut and oral tissues converge at Received 2 June 2014 the primary mouth, forming the buccopharyngeal membrane (BPM), a bilayer epithelium. Failure to form Received in revised form the opening between gut and mouth has significant ramifications, and many craniofacial disorders have 24 September 2014 been associated with defects in this process. Oral perforation is characterized by dissolution of the BPM, Accepted 25 September 2014 but little is known about this process. In humans, failure to form a continuous mouth opening is associated with mutations in Hedgehog (Hh) pathway members; however, the role of Hh in primary Keywords: mouth development is untested. Here, we show, using Xenopus, that Hh signaling is necessary and Hedgehog sufficient to initiate mouth formation, and that Hh activation is required in a dose-dependent fashion to Wnt determine the size of the mouth. This activity lies upstream of the previously demonstrated role for Wnt Primary mouth signal inhibition in oral perforation. We then turn to mouse mutants to establish that SHH and Gli3 are Xenopus Mouse indeed necessary for mammalian mouth development. -

Mouth Development

Mouth development The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Chen, Justin et al. “Mouth Development.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Developmental Biology 6, 5 (May 2017): e275 © 2017 The Authors As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/WDEV.275 Publisher Wiley-Blackwell Version Final published version Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/116900 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License Detailed Terms http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Advanced Review Mouth development Justin Chen,1,2† Laura A. Jacox,1,3,4†‡ Francesca Saldanha,1§ and Hazel Sive1,2* A mouth is present in all animals, and comprises an opening from the outside into the oral cavity and the beginnings of the digestive tract to allow eating. This review focuses on the earliest steps in mouth formation. In the first half, we con- clude that the mouth arose once during evolution. In all animals, the mouth forms from ectoderm and endoderm. A direct association of oral ectoderm and digestive endoderm is present even in triploblastic animals, and in chordates, this region is known as the extreme anterior domain (EAD). Further support for a single origin of the mouth is a conserved set of genes that form a ‘mouth gene program’ including foxA and otx2. In the second half of this review, we discuss steps involved in vertebrate mouth formation, using the frog Xenopus as a model. The vertebrate mouth derives from oral ectoderm from the anterior neural ridge, pharyngeal endoderm and cranial neural crest (NC).