Some Irish Quaker Naturalists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter 4

PHYCOLOGICAL NEWSLETTER A PUBLICATION OF THE PHYCOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA WINTER INSIDE THIS ISSUE: 2008 PSA Meeting 1 SPRING 2008 Meetings and Symposia 2 Editor: Courses 5 Juan Lopez-Bautista VOLUME 44 Job Opportunities 11 Department of Biological Sciences Trailblazer 28: Sophie C. Ducker 12 University of Alabama Island to honor UAB scientists 18 Tuscaloosa, AL 35487 Books 19 [email protected] Deadline for contributions 23 ∗Dr. Karen Steidinger (Florida Fish and 1 2008 Meeting of Wildlife Research Institute) presenting The Phycological Society of America a plenary talk entitled “Harmful algal blooms in North America: Common risks.” New Orleand, Louisiana, USA NUMBER 27-30 July The associated mini-symposium speakers will be Dr. Leanne Flewelling (Florida Fish he Phycological Society of America (PSA) will and Wildlife Research Institute) present- hold its 2008 annual meeting on July 27-30, ing a talk entitled “Unexpected vectors of 1 T2008 in New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. The brevetoxins to marine mammals” and Dr. meeting will be held on the campus of Loyola Jonathan Deeds (US FDA Center for Food University and is being hosted by Prof. James Wee Safety and Applied Nutrition) present- (Loyola University). The meeting will kick-off with ing a talk entitled “The evolving story of an opening mixer on the evening of Sunday, 27 July Gyrodinium galatheanum = Karlodinium and the scientific program will be Monday through micrum = Karlodinium veneficum. A ten- Wednesday, 28-30 July. The PSA banquet will be year perspective.” Wednesday evening at the Louisiana Swamp Ex- hibit at the Audubon Zoo. Optional field trips are *Dr. John W. -

CHIST1 Joseph Barcroft.Pmd

Anales de la Facultad de MedicinaJoseph Barcroft y la expedición anglo-americana a los Andes Peruanos ISSN 1025 - 5583 Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos Págs. 159-173 Historia Joseph Barcroft y la expedición anglo-americana a los Andes Peruanos (1921-1922) Oscar G. Pamo 1,2 Resumen Joseph Barcroft (1872-1947), fisiólogo británico de Cambridge, vino al Perú hacia fines de 1921 liderando la expedición angloamericana para estudiar las características fisiológicas que permiten a los humanos aclimatarse a la vida en las grandes alturas. Arribaron a Cerro de Pasco, realizando diversas mediciones y a diferentes altitudes, en ellos, en el personal norteamericano de la mina y en algunos nativos. Esta experiencia, publicada dos años más tarde, generaría en el doctor Carlos Monge Medrano (1884-1970) y otros investigadores nacionales el interés de conocer la biología y la patología del hombre andino, en 1927. Palabras clave Historia de la medicina, Perú; altitud; ecosistema andino; Barcroft, Joseph. Joseph Barcroft and the Anglo-American lideró la expedición angloamericana que a fines de 1921 expedition to the Peruvian Andes (1921-1922) vino a los Andes peruanos a estudiar la fisiología Abstract respiratoria del humano sometido a baja presión Joseph Barcroft (1872-1947), British Cambridge atmosférica. Sus conclusiones, que publicó dos años physiologist, came to Peru at the end of 1921 leading the después, dieron lugar a una respuesta del Dr. Carlos Monge Anglo-American expedition in order to study the Medrano en 1927. De allí en adelante, se realizó numerosas physiological characteristics that let human beings investigaciones para estudiar la salud y la enfermedad del acclimatize to live at high altitude environments. -

Hunt, Stephen E. "'Free, Bold, Joyous': the Love of Seaweed in Margaret Gatty and Other Mid–Victorian Writers." Environment and History 11, No

The White Horse Press Full citation: Hunt, Stephen E. "'Free, Bold, Joyous': The Love of Seaweed in Margaret Gatty and Other Mid–Victorian Writers." Environment and History 11, no. 1 (February 2005): 5–34. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/3221. Rights: All rights reserved. © The White Horse Press 2005. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism or review, no part of this article may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, including photocopying or recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission from the publishers. For further information please see http://www.whpress.co.uk. ʻFree, Bold, Joyousʼ: The Love of Seaweed in Margaret Gatty and Other Mid-Victorian Writers STEPHEN E. HUNT Wesley House, 10 Milton Park, Redfield, Bristol, BS5 9HQ Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT With particular reference to Gattyʼs British Sea-Weeds and Eliotʼs ʻRecollections of Ilfracombeʼ, this article takes an ecocritical approach to popular writings about seaweed, thus illustrating the broader perception of the natural world in mid-Victorian literature. This is a discursive exploration of the way that the enthusiasm for seaweed reveals prevailing ideas about propriety, philanthropy and natural theology during the Victorian era, incorporating social history, gender issues and natural history in an interdisciplinary manner. Although unchaperoned wandering upon remote shorelines remained a questionable activity for women, ʻseaweedingʼ made for a direct aesthetic engagement with the specificity of place in a way that conforms to Barbara Gatesʼs notion of the ʻVictorian female sublimeʼ. -

THE ETHICAL DILEMMA of SCIENCE and OTHER WRITINGS the Rockefeller Institute Press

THE ETHICAL DILEMMA OF SCIENCE AND OTHER WRITINGS The Rockefeller Institute Press IN ASSOCIATION WITH OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK 1960 @ 1960 BY THE ROCKEFELLER INSTITUTE PRESS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BY THE ROCKEFELLER INSTITUTE PRESS IN ASSOCIATION WITH OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number 60-13207 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE The Ethical Dilemma of Science Living mechanism 5 The present tendencies and the future compass of physiological science 7 Experiments on frogs and men 24 Scepticism and faith 39 Science, national and international, and the basis of co-operation 45 The use and misuse of science in government 57 Science in Parliament 67 The ethical dilemma of science 72 Science and witchcraft, or, the nature of a university 90 CHAPTER TWO Trailing One's Coat Enemies of knowledge 105 The University of London Council for Psychical Investigation 118 "Hypothecate" versus "Assume" 120 Pharmacy and Medicines Bill (House of Commons) 121 The social sciences 12 5 The useful guinea-pig 127 The Pure Politician 129 Mugwumps 131 The Communists' new weapon- germ warfare 132 Independence in publication 135 ~ CONTENTS CHAPTER THREE About People Bertram Hopkinson 1 39 Hartley Lupton 142 Willem Einthoven 144 The Donnan-Hill Effect (The Mystery of Life) 148 F. W. Lamb 156 Another Englishman's "Thank you" 159 Ivan P. Pavlov 160 E. D. Adrian in the Chair of Physiology at Cambridge 165 Louis Lapicque 168 E. J. Allen 171 William Hartree 173 R. H. Fowler 179 Joseph Barcroft 180 Sir Henry Dale, the Chairman of the Science Committee of the British Council 184 August Krogh 187 Otto Meyerhof 192 Hans Sloane 195 On A. -

Botanical Collecting in the Central Pacific Ocean Region, Part II

Botanical collecting in the central Pacific Ocean region, Part II Rhys Gardner This article is a continuation of Gardner (2007), grasses: "Cenchrus echinatus, Eleusine indica, which summarized botanizing activities in the central Digitaria sanguinalis, Panicum ... , Oplismenus Pacific Ocean region up to the year 1800. One burmanni (sic), Saccharum officinale " (Richard correction to that article is also noted. Part II covers 1833–4, p. viii). the nineteenth century up to the 1870s. The collections from D'Urville's voyage are at P. A The first important nineteenth century expedition of few D'Urville and Lesson collections from Tonga are discovery in our region was made under the cited by Hemsley (1894), but no Fijian collections, command of Louis Isidor Duperrey. His second-in- apparently, were made. command, Jules Sébastien César Dumont D'Urville, was also the official botanist, and was to be assisted The voyage of the Blonde, commanded by Captain by surgeons Prosper Garnot and René Primavere George Anson, Lord Byron, had as its melancholy Lesson. Their ship the Coquille sailed from Toulon in purpose the bearing home of the bodies of the 1822. They passed through the Tuamotus and the Hawaiian king and queen, who had died of measles Societies, and went on past Niue and Rotuma during their trip to London. It also carried a botanical without landing. France was regained in 1825. collector, James Macrae, in the employ of the D'Urville, with Bory St Vincent and Adolphe Horticultural Society of London. On the homeward Brongniart, wrote the three botanical volumes journey the Blonde made a day's stop at Mauke in relating this expedition's work. -

Contributors

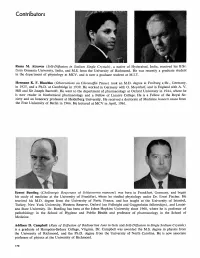

Contributors Rama M. Aiyawar (Self-Diffusion in Sodium Single Crystals), a native of Hyderabad, India, received his B.Sc. from Osmania University, India, and M.S. from the University of Richmond. He was recently a graduate student in the department of physiology at MCV, and is now a graduate student at M.I.T. Hermann K. F. Blaschko (Observations on Chromaffin Tissue) took an M.D . degree at Freiburg e/ Br., Germany, in 1925, and a Ph.D. at Cambridge in 1939. He worked in Germany with 0 . Meyerhof, and in England with A. V. Hill and Sir Joseph Barcroft. He went to the department of pharmacology at Oxford University in 1944, where he is now reader in biochemical pharmacology and a Fellow of Linacre College. He is a Fellow of the Royal So ciety and an honorary professor at Heidelberg University. He received a doctorate of Medicine honoris causa from the Free University of Berlin in 1966. He lectured at MCV in April, 1961. Ernest Buediog ( Cholinergic Responses of Schistosoma mansoni) was born in Frankfurt, Germany, and began his study of medicine at the University of Frankfurt, where he studied physiology under Dr. Ernst Fischer. He received his M.D. degree from the University of Paris, France, and has taught at the University of Istanbul, Turkey, New York University, Western Reserve, Oxford (on Fulbright and Guggenheim fellowships) , and Louisi ana State University. Dr. Bueding has been at the Johns Hopkins University since 1960, where he is professor of pathobiology in the School of Hygiene and Public Health and professor of pharmacology in the School of Medicine. -

A Review of Sub Tidal Kelp Forests in Ireland: from First Descriptions To

A review of sub tidal kelp forests in Ireland: from first descriptions to new habitat monitoring techniques Kathryn Schoenrock1, Kenan Chan1, Tony O'Callaghan2, Rory O'Callaghan2, Aaron Golden1, Stacy Krueger-Hadfield3, and Anne Marie Power1 1NUI Galway 2Seasearch Ireland 3University of Alabama at Birmingham April 28, 2020 Abstract Aim Kelp forests worldwide are important marine ecosystems that foster high primary to secondary productivity and multi- ple ecosystem services. These ecosystems are increasingly under threat from extreme storms, changing ocean temperatures, harvesting, and greater herbivore pressure at regional and global scales, necessitating urgent documentation of their histori- cal to present day distributions. Species range shifts to higher latitudes have already been documented in some species that dominate subtidal habitats within Europe. Very little is known about kelp forest ecosystems in Ireland, where rocky coastlines are dominated by Laminaria hyperborea. In order to rectify this substantial knowledge gap, we compiled historical records from an array of sources to present historical distribution, kelp and kelp forest recording effort over time, and present rational for the monitoring of kelp habitats to better understand ecosystem resilience. Location Ireland (Northern Ireland and Eire).´ Methods Herbaria, literature from the Linnaean society dating back to late 1700s, journal articles, government reports, and online databases were scoured for information on L. hyperborea. Information about kelp ecosystems was solicited from dive clubs and citizen science groups that are active along Ireland's coastlines. Results Data were used to create distribution maps, analyse methodology and technology used to record L. hyperborea presence and kelp ecosystems within Ireland. We discuss the recent surge in studies on Irish kelp ecosystems and fauna associated with kelp ecosystems that may be used as indicators of ecosystem health and suggest methodologies for continued monitoring. -

Landmarks in Pacific North America Marine Phycology

Landmarks in Pacific North America Marine Phycology GEORGE F. PAPENFUSS Labore arlo de Flcolo fa o partamento de 8iolog(8 Facultad de Cfenclas UN M KNOWLEDGE of the marine algae of the Pacific coast of orth America hegins with the 1791-95 expedition of Captain George Vancouver. (See Anderson, 1960, for an excellent account of this expedition. ) On the rec ommendation of the botanist Sir Joseph Banks (who as a young man had been a member of the scientific staff on Cook's first voyage, 1768--71), Archibald Menzies, a surgeon, was appointed botanist of the Vancouver expedition. Menzies had earlier served on a fur-trading vessel plying the northeastem Pacific and had collected plants from the Bering Strait to Nootka Sound, on the west coast of Vancouver Island, in the years 1787 and 1788 (Jepson, 1929b; Scagel, 1957, p. 4), but I hav e come across no records of algae collected by him at that time. As a young midshipman Vancouver had been to the northeastern Pacific with Cook's third voyage in 1778. Now, in 1791, his expedition consisted of two ships, the sloop Discovery and the armed tender Chatham. The ships cam e to the north Pacific by way of the Cape of Good Hope, Australia, New Zealand, Tahiti, and the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii). They sailed from Hawaii on March 16, 1792, sighted the Mendocino coast of Califomia ( or Nova Albion [New Britain], the name given to northem California and Oregon by Drake and the name by which thi s region was still known among English navigators in Vancouver's time) on April 18, and proceeded north to explore the coast. -

Sir Joseph Barcroft C.B.E., M.A., D.Sc., Hon. M.D., Hon. F.R.C.O.G., F.R.S

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core Obituary SIR JOSEPH BARCROFT, C.B.E., M.A., D.Sc., Hon. hI.D., Hon. F.R.C.O.G., F.R.S. The Nutrition Society is mourning the loss of its Chairman, Sir Joseph Barcroft, who . IP address: died suddenly from a heart attack in Cambridge on zr March. Surely no society ever had a more devoted, energetic and conscientious Chairman-but Barcroft was more than this, for in the Chair (as out of it) he would be at the same time both wise and 170.106.33.14 witty; and he combined an inflexible integrity and high purpose with tact and with a gay, happy charm; and much learning with simplicity and humility; and he was rich in human sympathy and understanding. , on Only those who served with him as Honorary officers, or on the Council, can know 26 Sep 2021 at 05:31:40 the full extent of the generous and unselfish work he did for the Society. He had been active in its interests from the start, having been one of the signatories of the ‘ mani- festo’ which led to its foundation, and having taken the Chair at its first discussion, at the inaugural scientific meeting in Cambridge on 18 October 1941. He consented to join the Committee in 1942, became Chairman of the English Group in 1% and , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at since 1945 had been Chairman of the Society. The Council were to have nominated him as President for the Session 1947-8,under the new constitution. -

Inside Living Cancer Cells Research Advances Through Bioimaging

PN Issue 104 / Autumn 2016 Physiology News Inside living cancer cells Research advances through bioimaging Symposium Gene Editing and Gene Regulation (with CRISPR) Tuesday 15 November 2016 Hodgkin Huxley House, 30 Farringdon Lane, London EC1R 3AW, UK Organised by Patrick Harrison, University College Cork, Ireland Stephen Hart, University College London, UK www.physoc.org/crispr The programme will include talks on CRISPR, but also showing the utility of techniques such as ZFNs and Talens. As well as editing, the use of these techniques to regulate gene expression will be explored both in the context of studying normal physiology and the mechanisms of disease. The use of the techniques in engineering cells and animals will be explored, as will techniques to deliver edited reagents and edited cells in vivo. Physiology News Editor Roger Thomas We welcome feedback on our membership magazine, or letters and suggestions for (University of Cambridge) articles for publication, including book reviews, from Physiological Society Members. Editorial Board Please email [email protected] Karen Doyle (NUI Galway) Physiology News is one of the benefits of membership of The Physiological Society, along with Rachel McCormack reduced registration rates for our high-profile events, free online access to The Physiological (University of Liverpool) Society’s leading journals, The Journal of Physiology and Experimental Physiology, and travel David Miller grants to attend scientific meetings. Membership of The Physiological Society offers you (University of Glasgow) access to the largest network of physiologists in Europe. Keith Siew (University of Cambridge) Join now to support your career in physiology: Austin Elliott Visit www.physoc.org/membership or call 0207 269 5728. -

Scientific Papers of Asa Gray, Vol II, 1841-1886

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com I ■ *- I University of Virginia Library QK3 G77 1889 V.2 SEL Scientific papers of Asa Gray, NX DD1 7DD 2CH LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA FROM THE BOOKS OF REV. HASLETT McKIM i : i M SCIENTIFIC PAPERS OF ASA GRAY SELECTED BY CHARLES SPRAGUE SARGENT VOL. II. ESSAYS; BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES 1841-1886 T O ■TT'H rp "» T BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY ffibe iiiiuTsiDc Pre?!*, £ambrit>or 18S9 3 .GJ 7 1883 1 560^ y, , . Copyright, 1889, Bt CHARLES S PRAGUE SARGENT. All rights reserved. ' The Riverside Frets, Cambridge, Mass , V. S. A. Electrotyped and Printed by II. 0. lloughtou & Company. CONTENTS. ESSAYS. PAGJ European Herbaria 1 Notes of a Botanical Excursion to the Mountains op North Carolina 22 The Longevity of Trees 71 The Flora of Japan 125 Sequoia and its History 142 Do Varieties Wear Out or tend to Wear Out .... 174 ^Estivation and its Terminology 181 A Pilgrimage to Torreya 189 Notes on the History of Helianthus Tubehosus .... 197 Forest Geography and Archeology 204 The Pertinacity and Predominance of Weeds .... 234 The Flora of North America 243 Gender of Names of Varieties 257 Characteristics of the North American Flora .... 260 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES. Brown and Humboldt 283 Augustin-Pyramus De Candolle 289 Benjamin D. Greene 310 Charles Wilkes Short 312 Francis Boott 315 William Jackson Hooker 321 John Lindley 333 William Henry Harvey 337 Henry P. -

HUNTIA a Journal of Botanical History

HUNTIA A Journal of Botanical History VOLUME 15 NUMBER 2 2015 Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh The Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, a research division of Carnegie Mellon University, specializes in the history of botany and all aspects of plant science and serves the international scientific community through research and documentation. To this end, the Institute acquires and maintains authoritative collections of books, plant images, manuscripts, portraits and data files, and provides publications and other modes of information service. The Institute meets the reference needs of botanists, biologists, historians, conservationists, librarians, bibliographers and the public at large, especially those concerned with any aspect of the North American flora. Huntia publishes articles on all aspects of the history of botany, including exploration, art, literature, biography, iconography and bibliography. The journal is published irregularly in one or more numbers per volume of approximately 200 pages by the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation. External contributions to Huntia are welcomed. Page charges have been eliminated. All manuscripts are subject to external peer review. Before submitting manuscripts for consideration, please review the “Guidelines for Contributors” on our Web site. Direct editorial correspondence to the Editor. Send books for announcement or review to the Book Reviews and Announcements Editor. Subscription rates per volume for 2015 (includes shipping): U.S. $65.00; international $75.00. Send orders for subscriptions and back issues to the Institute. All issues are available as PDFs on our Web site, with the current issue added when that volume is completed. Hunt Institute Associates may elect to receive Huntia as a benefit of membership; contact the Institute for more information.