To Download Your Copy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2006 Restore Omaha Program

Friday, November 3 7-10 p.m. Opening Reception Joslyn Castle – 3902 Davenport St. Meet the speakers and exhibitors while viewing one of Omaha’s architectural gems. Reception sponsored by the B. G. Peterson Co, Dundee Bank and the Nebraska State Historical Society Saturday, November 4 VENTS University of Nebraska at Omaha’s Milo Bail Student Center at 62nd and Dodge Streets 8:00 a.m. Registration. Exhibits, Bookstore and Tool area open. E Refreshments sponsored by the University of Nebraska Medical Center and the Nebraska Medical Center 9:00 a.m. Bob Yapp Keynote Address “Turning Historic Neighborhoods Around” Strauss Performing Arts Center Yapp’s visit made possible by a grant from the Charles Evan Hughes Fund of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and funding from the Nebraska Humanities Council and the Nebraska Arts Council. 10:30 to 12:30 – Exhibits and Bookstore and Tool Areas Open Milo Bail Student Center Ballroom and Maverick Buffet Room Ask An Expert – Milo Bail Student Ballroom John Leeke 10:30 to 11:30 CHEDULE OF Bob Yapp 11:30 to 12:30 S 12:30 - 1:30 p.m. Breakout Session 1 1:45 - 2:45 p.m. Breakout Session 2 2:45 - 3:00 p.m. Refreshments – 3rd Floor Milo Bail Student Center Refreshments sponsored by the University of Nebraska Medical Center and the Nebraska Medical Center 3:00 - 4:00 p.m. Breakout Session 3 4:15 – 5:15 p.m. Breakout Session 4 All Breakout Sessions will be in the Milo Bail Student Center 3rd Floor Breakout rooms and in the Strauss Performing Arts Center Auditorium Sunday, November 5 9 to 1 p.m. -

City of Omaha Combined Sewer Overflow Annual Report

City of Omaha Combined Sewer Overflow Annual Report NPDES Permit No. NE0133680 October 1, 2010 through September 30, 2011 Table of Contents I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 3 II. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ 3 A. Nine Minimum Controls (NMC) ............................................................................................ 4 B. LTCP Documentation .............................................................................................................. 4 C. Compliance Schedule ............................................................................................................... 4 D. CSO Outfall Monitoring .......................................................................................................... 5 E. In-stream Monitoring ............................................................................................................... 5 F. Other Information .................................................................................................................... 5 III. Nine Minimum Controls ....................................................................................................................... 6 A. Proper Operation and Maintenance (O & M) ....................................................................... 6 B. Maximize Use of the Collection -

Number 101 • Winter 2003

Newsletter Association For Recorded Sound Collections Number 101 • Winter 2003 th Philadelphia Hosts 37 ARSC Conference Events th The 37 annual ARSC conference will be held in Philadelphia, on the May 28-31, 2003. 37th Annual ARSC campus of the University of Pennsylvania, May 28-31, 2003. Founded by Conference, Philadelphia, PA. Benjamin Franklin in 1749, the University offered the nation’s first modern http://www.library.upenn.edu/ARSC/ liberal arts curriculum and now supports 4 undergraduate and 12 graduate and professional schools with a total enrollment of over 22,000 students. March 22-25, 2003. 114th 2003 AES Conven- Conference sessions will be held in Houston Hall, located in the center of tion, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. campus. The country’s first student union, Houston Hall was built in 1894 http://www.aes.org/events/114/ and was recently re- April 27, 2003. Mechanical Music stored, opening in Extravaganza, Wayne, New Jersey. 2000 with new stu- http://www.antique-sound.com/MME/show.html dent lounges, reno- vated meeting space, May 23-25, 2003. 23rd International AES and a food court. Conference—Signal processing in audio re- The opening recep- cording and reproduction, Helsinger, Denmark. http://www.aes.org/events/23/ tion will be hosted by the University of June 19-25, 2003. ALA Annual Conference, Pennsylvania Librar- Toronto, Ontario. ies and will be held in http://www.ala.org/events/annual2003/ the Van Pelt-Dietrich Library Center’s June 14-15 28th, 2003. Annual Phonograph Kamin Gallery, where & Music Box Show and Sale, Union, Illinois. University of Pennsylvania Campus. -

Appendix B – Transportation Profile

APPENDIX B TRANSPORTATION PROFILE Transportation Inventory Roadways in the MAPA Region The network of streets, highways, and bridges represents the primary form of transportation in the MAPA TMA. From residential streets to interstate freeways, it is utilized daily by the vast majority of residents in the metro area to get from point A to point B. In recent decades, hundreds of millions of dollars have been spent to construct and maintain the system that exists today. Ensuring that the roadway system continues to be safe and provides a high-degree mobility for residents and businesses is critical to the region’s future. The MAPA LRTP provides the metro area with a roadmap for anticipated transportation improvements. While the 30-year planning timeframe inherently carries with it a high level of uncertainty, it is nonetheless important to periodically assess the region’s transportation system and evaluate long range plans and goals. Traffic levels have grown rapidly in recent decades in the MAPA region; however, traffic growth slowed for several years following the economic recession of 2008. Since that time traffic growth has slowly begun to increase as population and employment continue to increase. Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic and social distancing had significant impacts in reducing traffic on the region’s roadways for weeks. However, at this time it is unclear whether there will be long-term impacts of the precautions being taken to slow the spread of the virus as communities plan for reopening businesses, schools and other venues. In many communities throughout the region, the roadway system in the metro area has not kept pace with new, suburban growth. -

Digital Audio Broadcasting : Principles and Applications of Digital Radio

Digital Audio Broadcasting Principles and Applications of Digital Radio Second Edition Edited by WOLFGANG HOEG Berlin, Germany and THOMAS LAUTERBACH University of Applied Sciences, Nuernberg, Germany Digital Audio Broadcasting Digital Audio Broadcasting Principles and Applications of Digital Radio Second Edition Edited by WOLFGANG HOEG Berlin, Germany and THOMAS LAUTERBACH University of Applied Sciences, Nuernberg, Germany Copyright ß 2003 John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England Telephone (þ44) 1243 779777 Email (for orders and customer service enquiries): [email protected] Visit our Home Page on www.wileyeurope.com or www.wiley.com All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England, or emailed to [email protected], or faxed to (þ44) 1243 770571. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the Publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. -

Sponsored by Union Bank February 23, 2013 I Am Writing to Express My Sincere Gratitude for Your Generosity

Sponsored by Union Bank February 23, 2013 I am writing to express my sincere gratitude for your generosity. As I humbly stood waiting for my name to be called [at the Scholarship Awards ceremony], I walked proud and full of emotion as I heard my name through the loud speakers. After I was photographed, I sat down and then opened up the brochure in order to see my name once more, and that is when it hit me; I was overcome with an immense feeling of appreciation as I thought to myself about what a prestigious recognition I just received. The feeling of accomplishment that I felt at that moment will remain with me forever. It is people like you who give me the strength and motivation to keep my dream alive of earning a bachelor’s degree in Business Administration. I am inspired like never before. Your thoughtful donation helps me as I continue my plight to better myself and those around me. Helping this world to become a better place is my ultimate goal in life, and you have lit a fire beneath me! I extend my heart out to you to say ‘thank you’ for helping me in my time of need. --Cypress College Scholarship Recipient Minds. Motivated. You inspire the future. You believe in the transformational power of a classroom. You light the way for a new generation of students. Your commitment creates the leaders of tomorrow. For your dedication to education, we salute you. Union Bank is proud to support Cypress College and sponsor the Americana Awards. -

Implementation Considerations for the Introduction and Transition to Digital Terrestrial Sound and Multimedia Broadcasting

Report ITU-R BS.2384-0 (07/2015) Implementation considerations for the introduction and transition to digital terrestrial sound and multimedia broadcasting BS Series Broadcasting service (sound) ii Rep. ITU-R BS.2384-0 Foreword The role of the Radiocommunication Sector is to ensure the rational, equitable, efficient and economical use of the radio- frequency spectrum by all radiocommunication services, including satellite services, and carry out studies without limit of frequency range on the basis of which Recommendations are adopted. The regulatory and policy functions of the Radiocommunication Sector are performed by World and Regional Radiocommunication Conferences and Radiocommunication Assemblies supported by Study Groups. Policy on Intellectual Property Right (IPR) ITU-R policy on IPR is described in the Common Patent Policy for ITU-T/ITU-R/ISO/IEC referenced in Annex 1 of Resolution ITU-R 1. Forms to be used for the submission of patent statements and licensing declarations by patent holders are available from http://www.itu.int/ITU-R/go/patents/en where the Guidelines for Implementation of the Common Patent Policy for ITU-T/ITU-R/ISO/IEC and the ITU-R patent information database can also be found. Series of ITU-R Reports (Also available online at http://www.itu.int/publ/R-REP/en) Series Title BO Satellite delivery BR Recording for production, archival and play-out; film for television BS Broadcasting service (sound) BT Broadcasting service (television) F Fixed service M Mobile, radiodetermination, amateur and related satellite services P Radiowave propagation RA Radio astronomy RS Remote sensing systems S Fixed-satellite service SA Space applications and meteorology SF Frequency sharing and coordination between fixed-satellite and fixed service systems SM Spectrum management Note: This ITU-R Report was approved in English by the Study Group under the procedure detailed in Resolution ITU-R 1. -

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection a Handlist

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection A Handlist A wide-ranging collection of c. 4000 individual popular songs, dating from the 1920s to the 1970s and including songs from films and musicals. Originally the personal collection of the singer Rita Williams, with later additions, it includes songs in various European languages and some in Afrikaans. Rita Williams sang with the Billy Cotton Club, among other groups, and made numerous recordings in the 1940s and 1950s. The songs are arranged alphabetically by title. The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection is a closed access collection. Please ask at the enquiry desk if you would like to use it. Please note that all items are reference only and in most cases it is necessary to obtain permission from the relevant copyright holder before they can be photocopied. Box Title Artist/ Singer/ Popularized by... Lyricist Composer/ Artist Language Publisher Date No. of copies Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Dans met my Various Afrikaans Carstens- De Waal 1954-57 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Careless Love Hart Van Steen Afrikaans Dee Jay 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Ruiter In Die Nag Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Van Geluk Tot Verdriet Gideon Alberts/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Wye, Wye Vlaktes Martin Vorster/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs My Skemer Rapsodie Duffy -

名前 アーティスト アルバム ジャンル 分 年 Goodbye Earl 34Th CMA

名前 アーティスト アルバム ジャンル 分 年 Goodbye Earl 34th CMA Awards Music By Nominated Artsts カントリー 5.0 Goodbye Earl Dixie Chicks Fly カントリー 4.3 2001 Goodbye Is Alle We Have Alison Krauss & Union Station Lonely Runs Both Ways カントリー 3.9 2004 Goodbye Makes The Saddest Sound Billy Yates Yates Country & Folk3.3 Goodbye Marie LiveWire 598 598 Wired! カントリー 2.7 1990 Good-Bye Old Pal Bill Monroe Sixteen Gems カントリー 2.7 1945 Goodbye Train Deana Carter I'm Just A Girl カントリー 4.6 2003 Goodbye Train Deana Carter I'm Just A Girl カントリー 4.6 2003 Goodbye Wheeling Pam Tillis It's All Relative - Tillis Sings Tillis カントリー 3.7 2002 Goodbye,Lonesome,Hello,Baby Doll Johnny Horton The Golden Country Hits 05 Release Me カントリー 2.4 Goodnight Dallas Carlene Carter I Fell In Love カントリー 3.7 1990 Goodnight Irene Red Foley & Ernest Tubb The Golden Country Hits 07 Fraulein カントリー 3.0 Goodnight Irene The Chieftains Another Country World 4.3 1992 Gosh, I Miss You Jim & Jesse And The Virginia Boys Country Misic And Bluegrass At Newport 1963-Newport Folk Festival カントリー 2.1 1963 Gospel Plow Jerry Sullivan & Tammy Joyful Noise カントリー 2.2 Got A Feelin' For Ya Kelly Willis What I Deserve カントリー 3.4 1999 Got A Hold On Me Shania Twain Shania Twain カントリー 2.2 1993 Got Leavin' On Her Mind The Statler Brothers Innerview カントリー 1.6 Got To Be Certain Kylie Minogue Ultimate Kylie ポップ 3.3 1988 Gotta Keep Moving Kellie Pickler Small Town Girl Country & Folk3.5 2006 Gotta Lot Of Rhythm Patsy Cline Best Of Country Ladies カントリー 2.4 Gotta Lot Of Rhythm In My Soul Patsy Cline Sweet Dreams With Patsy Cline カントリー 2.4 Gotta' Sell Them Chickens Hank Thompson Hank Thompson And Friends Country & Folk3.0 1997 Gotta Travel On Lewis, Scruggs & Long Lifetimes Country & Folk2.7 2007 Gracie The McLains More Fun Than We Ought To Have カントリー 2.8 Graduation Prayer Williams & Clark Expedition The Old Kentucky Road カントリー 2.7 2004 Graffiti Bridge Deana Carter Did I Shave My Legs For This? カントリー 3.7 Grammy Medley: (See Comments) Larry Gatlin & The Gatlin Brothers Live At 8:00 P.M. -

Radiotimes-July1967.Pdf

msmm THE POST Up-to-the-Minute Comment IT is good to know that Twenty. Four Hours is to have regular viewing time. We shall know when to brew the coffee and to settle down, as with Panorama, to up-to- the-minute comment on current affairs. Both programmes do a magnifi- cent job of work, whisking us to all parts of the world and bringing to the studio, at what often seems like a moment's notice, speakers of all shades of opinion to be inter- viewed without fear or favour. A Memorable Occasion One admires the grasp which MANYthanks for the excellent and members of the team have of their timely relay of Die Frau ohne subjects, sombre or gay, and the Schatten from Covent Garden, and impartial, objective, and determined how strange it seems that this examination of controversial, and opera, which surely contains often delicate, matters: with always Strauss's s most glorious music. a glint of humour in the right should be performed there for the place, as with Cliff Michelmore's first time. urbane and pithy postscripts. Also, the clear synopsis by Alan A word of appreciation, too, for Jefferson helped to illuminate the the reporters who do uncomfort- beauty of the story and therefore able things in uncomfortable places the great beauty of the music. in the best tradition of news ser- An occasion to remember for a Whitstabl*. � vice.-J. Wesley Clark, long time. Clive Anderson, Aughton Park. Another Pet Hate Indian Music REFERRING to correspondence on THE Third Programme recital by the irritating bits of business in TV Subbulakshmi prompts me to write, plays, my pet hate is those typists with thanks, and congratulate the in offices and at home who never BBC on its superb broadcasts of use a backing sheet or take a car- Indian music, which I have been bon copy. -

1971-06-05 the Main Point-Page 20

08120 JUNE 5, 1971 $1.25 A BILLBOARD PUBLICATION t..bl)b;,!RIKE100*-ri.3wZ9 F _) 72 ">¡Ai'2(HAl\I; J 4A1-EN SEVENTY -SEVENTH YEAR BOX 10005 The International i i;N;lEf?. CO 80210 Music-Record-Tape Newsweekly CARTRIDGE TV PAGE 16 HOT 100 PAGE 56 TOP LP'S PAGES 54, 55 C S Sales Soari Car Tapes osts p Puts Pub on ® 5 >s .f*'? Sets bîversiIîc .p t® Sign on rk; Asks 5 Mil By LEE ZHITO By MIKE GROSS NEW YORK - CBS Inter- and today has expanded its own- Ci;ssette Units national enters its second decade ership in foreign subsidiaries to NEW YORK -Capitol Rec- operation of the Capitol Record with an estimated $100 million 24 countries. Its representation By RADCLIFFE JOE ords is planning to unload Club. in annual sales, and a program in the international marketplace NEW YORK - Car Tapes, its music publishing division, Bhaskar Menon, newly ap- - Glenwood Music. of accelerated expansion and consists of countries which are Inc. will phase out two of its Beechwood of Capitol diversification. The asking price for the firm is pointed president responsible for approximately 95 three auto cassette units, pos- up The company started with percent of the record industry's reported to be $5 million. One Records, has been shaking sibly by year's end. The Cali- picture firms in three countries abroad, dollar volume outside of the fornia -based company had three of the bids under consideration the diskery's structural U.S. with price tags has come from Longine's, which during the past few weeks and units available of publishing t' : Harvey Schein, president of $80 to $160. -

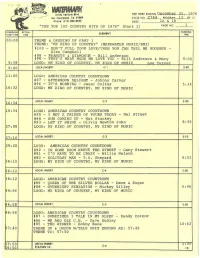

50 L 976 TOP 100 C

10700 Venture Blvd. FOR WEEK ENDING, December 2 s 1 l 976 No. Hollywood, c •. 91&04 CYCLE N{). C 7 6 4 PROGRAM l 3 OF 13 -Pnone· (213) 980-~90 SIDES, & lA lB TOP 100 COUNTRY HITS OF 1976" (Part 1) PAGE NO SCHEOUtEO ACTUAi • uNNING ELEMENT START TIME TIME TIME 00 : 00 THEME & OPENING OF PART 1 THEME: "MY KIND OF COUNTRY" (MARKWATER MUSIC/BMI) #100 - DON'T PULL YOUR LOVE/ THEN YOU CAN TELL ME GOODBYE - Glen Campbell #99 - PEANUTS & DIAMONDS - Bill Anderson #98 - THAT'S WHAT MADE ME LOVE YOU - Bill Anderson & Mary 9 :00 8:58 LOGO : MY KIND OF COUNTRY. MY KIND OF MTTSIC T,OU 'I'll rni=>r 9 : 00 LOCAL INSERT· C-1 2:00 11:00 LOGO: AMERICAN COUNTRY COUNTDOWN #97 - AFTERNOON DELIGHT - Johnny Carver #96 - IT Is MORNING - Jessi Colter 5 : 34 16:32 LOGO: MY KIND OF COUNTRY, MY KIND OF MUSIC 16·34 LOCAL INSERT : C-2 2:00 18:34 LOGO: AMERICAN COUNTRY COUNTDOWN #95 - I MET A FRIEND OF YOURS TODAY - Mel Street #94 - SUN COMING UP - Nat Stuckey #93 - LET IT SHINE - Olivia Newton John 8 : 36 27:08 LOGO: MY KIND OF COUNTRY, MY KIND OF MUSIC 27:10 LOCAL INSERT: C-3 2:10 29:20 LOGO: AMERICAN COUNTRY COUNTDOWN #92 - IN SOME ROOM ABOVE THE STREET - Gary Stewart #91 - I'D HAVE TO BE CRAZY - Willie Nelson #90 - SOLITARY MAN - T.G. Shepard 6:52 36:10 LOGO: MY KIND OF COUNTRY, MY KIND OF MUSIC 36:12 LOCAL INSERT: C-4 2 :00 38:12 LOGO: AMERICAN COUNTRY COUNTDOWN #89 - QUEEN OF THE SILVER DOLLAR - Dave & Sugar #88 - OVERNIGHT SENSATION - Mickey Gilley 6:46 44:56 LOGO: MY KIND OF COUNTRY, MY KIND .OF MUSIC 44:58 LOCAL INSERT : C-5 2:00 46:58 LOGO : AMERICAN COUNTRY COUNTDOWN #87 - SOMETIMES I TALK IN MY SLEEP - Randy Cornor #86 - ME AND OLE C.B.