Macrophages in Healing Wounds: Paradoxes and Paradigms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Energy Healing

57618_CH03_Pass2.QXD 10/30/08 1:19 PM Page 61 © Jones and Bartlett Publishers, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION. CHAPTER 3 Energy Healing Our remedies oft in ourselves do lie. —WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE LEARNING OBJECTIVES 1. Describe the types of energy. 2. Explain the universal energy field (UEF). 3. Explain the human energy field (HEF). 4. Describe the seven auric layers. 5. Describe the seven chakras. 6. Define the concept of energy healing. 7. Describe various types of energy healing. INTRODUCTION For centuries, traditional healers worldwide have practiced methods of energy healing, viewing the body as a complex energy system with energy flowing through or over its surface (Rakel, 2007). Until recently, the Western world largely ignored the Eastern interpretation of humans as energy beings. However, times have changed dramatically and an exciting and promising new branch of academic inquiry and clinical research is opening in the area of energy healing (Oschman, 2000; Trivieri & Anderson, 2002). Scientists and energy therapists around the world have made discoveries that will forever alter our picture of human energetics. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is conducting research in areas such as energy healing and prayer, and major U.S. academic institutions are conducting large clinical trials in these areas. Approaches in exploring the concepts of life force and healing energy that previously appeared to compete or conflict have now been found to support each other. Conner and Koithan (2006) note 61 57618_CH03_Pass2.QXD 10/30/08 1:19 PM Page 62 © Jones and Bartlett Publishers, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION. 62 CHAPTER 3 • ENERGY HEALING that “with increased recognition and federal funding for energetic healing, there is a growing body of research that supports the use of energetic healing interventions with patients” (p. -

Purinergic Signalling in Skin

PURINERGIC SIGNALLING IN SKIN AINA VH GREIG MA FRCS Autonomic Neuroscience Institute Royal Free and University College School of Medicine Rowland Hill Street Hampstead London NW3 2PF in the Department of Anatomy and Developmental Biology University College London Gower Street London WCIE 6BT 2002 Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of London ProQuest Number: U643205 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U643205 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT Purinergic receptors, which bind ATP, are expressed on human cutaneous kératinocytes. Previous work in rat epidermis suggested functional roles of purinergic receptors in the regulation of proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis, for example P2X5 receptors were expressed on kératinocytes undergoing proliferation and differentiation, while P2X? receptors were associated with apoptosis. In this thesis, the aim was to investigate the expression of purinergic receptors in human normal and pathological skin, where the balance between these processes is changed. A study was made of the expression of purinergic receptor subtypes in human adult and fetal skin. -

Wound Classification

Wound Classification Presented by Dr. Karen Zulkowski, D.N.S., RN Montana State University Welcome! Thank you for joining this webinar about how to assess and measure a wound. 2 A Little About Myself… • Associate professor at Montana State University • Executive editor of the Journal of the World Council of Enterstomal Therapists (JWCET) and WCET International Ostomy Guidelines (2014) • Editorial board member of Ostomy Wound Management and Advances in Skin and Wound Care • Legal consultant • Former NPUAP board member 3 Today We Will Talk About • How to assess a wound • How to measure a wound Please make a note of your questions. Your Quality Improvement (QI) Specialists will follow up with you after this webinar to address them. 4 Assessing and Measuring Wounds • You completed a skin assessment and found a wound. • Now you need to determine what type of wound you found. • If it is a pressure ulcer, you need to determine the stage. 5 Assessing and Measuring Wounds This is important because— • Each type of wound has a different etiology. • Treatment may be very different. However— • Not all wounds are clear cut. • The cause may be multifactoral. 6 Types of Wounds • Vascular (arterial, venous, and mixed) • Neuropathic (diabetic) • Moisture-associated dermatitis • Skin tear • Pressure ulcer 7 Mixed Etiologies Many wounds have mixed etiologies. • There may be both venous and arterial insufficiency. • There may be diabetes and pressure characteristics. 8 Moisture-Associated Skin Damage • Also called perineal dermatitis, diaper rash, incontinence-associated dermatitis (often confused with pressure ulcers) • An inflammation of the skin in the perineal area, on and between the buttocks, into the skin folds, and down the inner thighs • Scaling of the skin with papule and vesicle formation: – These may open, with “weeping” of the skin, which exacerbates skin damage. -

Repair, Regeneration, and Fibrosis Gregory C

91731_ch03 12/8/06 7:33 PM Page 71 3 Repair, Regeneration, and Fibrosis Gregory C. Sephel Stephen C. Woodward The Basic Processes of Healing Regeneration Migration of Cells Stem cells Extracellular Matrix Cell Proliferation Remodeling Conditions That Modify Repair Cell Proliferation Local Factors Repair Repair Patterns Repair and Regeneration Suboptimal Wound Repair Wound Healing bservations regarding the repair of wounds (i.e., wound architecture are unaltered. Thus, wounds that do not heal may re- healing) date to physicians in ancient Egypt and battle flect excess proteinase activity, decreased matrix accumulation, Osurgeons in classic Greece. The liver’s ability to regenerate or altered matrix assembly. Conversely, fibrosis and scarring forms the basis of the Greek myth involving Prometheus. The may result from reduced proteinase activity or increased matrix clotting of blood to prevent exsanguination was recognized as accumulation. Whereas the formation of new collagen during the first necessary event in wound healing. At the time of the repair is required for increased strength of the healing site, American Civil War, the development of “laudable pus” in chronic fibrosis is a major component of diseases that involve wounds was thought to be necessary, and its emergence was not chronic injury. appreciated as a symptom of infection but considered a positive sign in the healing process. Later studies of wound infection led The Basic Processes of Healing to the discovery that inflammatory cells are primary actors in the repair process. Although scurvy (see Chapter 8) was described in Many of the basic cellular and molecular mechanisms necessary the 16th century by the British navy, it was not until the 20th for wound healing are found in other processes involving dynamic century that vitamin C (ascorbic acid) was found to be necessary tissue changes, such as development and tumor growth. -

Extracellular Matrix Grafts: from Preparation to Application (Review)

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MOleCular meDICine 47: 463-474, 2021 Extracellular matrix grafts: From preparation to application (Review) YONGSHENG JIANG1*, RUI LI1,2*, CHUNCHAN HAN1 and LIJIANG HUANG1 1Science and Education Management Center, The Affiliated Xiangshan Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Ningbo, Zhejiang 315700; 2School of Chemistry, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510275, P.R. China Received July 30, 2020; Accepted December 3, 2020 DOI: 10.3892/ijmm.2020.4818 Abstract. Recently, the increasing emergency of traffic acci- Contents dents and the unsatisfactory outcome of surgical intervention are driving research to seek a novel technology to repair trau- 1. Introduction matic soft tissue injury. From this perspective, decellularized 2. ECM-G characterization matrix grafts (ECM-G) including natural ECM materials, and 3. Methods of decellularization treatments their prepared hydrogels and bioscaffolds, have emerged as 4. Removal of residual cellular components and chemicals possible alternatives for tissue engineering and regenerative 5. Application of ECM-P in regenerative medicine medicine. Over the past decades, several physical and chemical 6. Challenges and future outlook on ECM-P decellularization methods have been used extensively to deal 7. Conclusions with different tissues/organs in an attempt to carefully remove cellular antigens while maintaining the non-immunogenic ECM components. It is anticipated that when the decellular- 1. Introduction ized biomaterials are seeded with cells in vitro or incorporated into irregularly shaped defects in vivo, they can provide the The extracellular matrix (ECM) derived from organs/tissues is appropriate biomechanical and biochemical conditions for a complex, highly organized assembly of macromolecules with directing cell behavior and tissue remodeling. -

Wound Care: the Basics

Wound Care: The Basics Suzann Williams-Rosenthal, RN, MSN, WOC, GNP Norma Branham, RN, MSN, WOC, GNP University of Virginia May, 2010 What Type of Wound is it? How long has it been there? Acute-generally heal in a couple weeks, but can become chronic: Surgical Trauma Chronic -do not heal by normal repair process-takes weeks to months: Vascular-venous stasis, arterial ulcers Pressure ulcers Diabetic foot ulcers (neuropathic) Chronic Wounds Pressure Ulcer Staging Where is it? Where is it located? Use anatomical location-heel, ankle, sacrum, coccyx, etc. Measurements-in centimeters Length X Width X Depth • Length = greatest length (head to toe) • Width = greatest width (side to side) • Depth = measure by marking the depth with a Q- Tip and then hold to a ruler Wound Characteristics: Describe by percentage of each type of tissue: Granulation tissue: • red, cobblestone appearance (healing, filling in) Necrotic: • Slough-yellow, tan dead tissue (devitalized) • Eschar-black/brown necrotic tissue, can be hard or soft Evaluating additional tissue damage: Undermining Separation of tissue from the surface under the edge of the wound • Describe by clock face with patients head at 12 (“undermining is 1 cm from 12 to 4 o’clock”) Tunneling Channel that runs from the wound edge through to other tissue • “tunneling at 9 o’clock, measuring 3 cm long” Wound Drainage and Odor Exudate Fluid from wound • Document the amount, type and odor • Light, moderate, heavy • Drainage can be clear, sanguineous (bloody), serosanguineous (blood-tinged), -

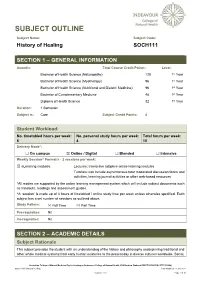

SOCH111 History of Healing Last Modified: 17-Jun-2021

SUBJECT OUTLINE Subject Name: Subject Code: History of Healing SOCH111 SECTION 1 – GENERAL INFORMATION Award/s: Total Course Credit Points: Level: Bachelor of Health Science (Naturopathy) 128 1st Year Bachelor of Health Science (Myotherapy) 96 1st Year Bachelor of Health Science (Nutritional and Dietetic Medicine) 96 1st Year Bachelor of Complementary Medicine 48 1st Year Diploma of Health Science 32 1st Year Duration: 1 Semester Subject is: Core Subject Credit Points: 4 Student Workload: No. timetabled hours per week: No. personal study hours per week: Total hours per week: 6 4 10 Delivery Mode*: ☐ On campus ☒ Online / Digital ☐ Blended ☐ Intensive Weekly Session^ Format/s - 2 sessions per week: ☒ eLearning modules: Lectures: Interactive adaptive online learning modules Tutorials: can include asynchronous tutor moderated discussion forum and activities, learning journal activities or other web-based resources *All modes are supported by the online learning management system which will include subject documents such as handouts, readings and assessment guides. ^A ‘session’ is made up of 3 hours of timetabled / online study time per week unless otherwise specified. Each subject has a set number of sessions as outlined above. Study Pattern: ☒ Full Time ☒ Part Time Pre-requisites: Nil Co-requisites: Nil SECTION 2 – ACADEMIC DETAILS Subject Rationale This subject provides the student with an understanding of the history and philosophy underpinning traditional and other whole medical systems from early human existence to the present day in diverse cultures worldwide. Social, Australian College of Natural Medicine Pty Ltd trading as Endeavour College of Natural Health, FIAFitnation (National CRICOS #00231G, RTO #31489) SOCH111 History of Healing Last modified: 17-Jun-2021 Version: 27.0 Page 1 of 10 cultural and political developments are considered in the evolution of healing and medicine, as well as the parallel developments in anatomy, physiology and other sciences. -

Evidence for the Nonmuscle Nature of The" Myofibroblast" of Granulation Tissue and Hypertropic Scar. an Immunofluorescence Study

American Journal of Pathology, Vol. 130, No. 2, February 1988 Copyright i American Association of Pathologists Evidencefor the Nonmuscle Nature ofthe "Myofibroblast" ofGranulation Tissue and Hypertropic Scar An Immunofluorescence Study ROBERT J. EDDY, BSc, JANE A. PETRO, MD, From the Department ofAnatomy, the Department ofSurgery, and JAMES J. TOMASEK, PhD Division ofPlastic and Reconstructive Surgery, and the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, New York Medical College, Valhalla, New York Contraction is an important phenomenon in wound cell-matrix attachment in smooth muscle and non- repair and hypertrophic scarring. Studies indicate that muscle cells, respectively. Myofibroblasts can be iden- wound contraction involves a specialized cell known as tified by their intense staining of actin bundles with the myofibroblast, which has morphologic character- either anti-actin antibody or NBD-phallacidin. Myofi- istics of both smooth muscle and fibroblastic cells. In broblasts in all tissues stained for nonmuscle but not order to better characterize the myofibroblast, the au- smooth muscle myosin. In addition, nonmuscle myo- thors have examined its cytoskeleton and surrounding sin was localized as intracellular fibrils, which suggests extracellular matrix (ECM) in human burn granula- their similarity to stress fibers in cultured fibroblasts. tion tissue, human hypertrophic scar, and rat granula- The ECM around myofibroblasts stains intensely for tion tissue by indirect immunofluorescence. Primary fibronectin but lacks laminin, which suggests that a antibodies used in this study were directed against 1) true basal lamina is not present. The immunocytoche- smooth muscle myosin and 2) nonmuscle myosin, mical findings suggest that the myofibroblast is a spe- components ofthe cytoskeleton in smooth muscle and cialized nonmuscle type of cell, not a smooth muscle nonmuscle cells, respectively, and 3) laminin and 4) cell. -

Extracellular Matrix Degradation and Remodeling in Development and Disease

Downloaded from http://cshperspectives.cshlp.org/ on September 30, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Extracellular Matrix Degradation and Remodeling in Development and Disease Pengfei Lu1,2, Ken Takai2, Valerie M. Weaver3, and Zena Werb2 1Breakthrough Breast Cancer Research Unit, Paterson Institute for Cancer Research and Wellcome Trust Centre for Cell Matrix Research, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Manchester, Manchester M20 4BX, United Kingdom 2Department of Anatomy and Program in Developmental Biology, University of California, San Francisco, California 94143-0452 3Department of Surgery and Center for Bioengineering and Tissue Regeneration, University of California, San Francisco, California 94143 Correspondence: [email protected] The extracellular matrix (ECM) serves diverse functions and is a major component of the cellular microenvironment. The ECM is a highly dynamic structure, constantly undergoing a remodeling process where ECM components are deposited, degraded, or otherwise modified. ECM dynamics are indispensible during restructuring of tissue architecture. ECM remodeling is an important mechanism whereby cell differentiation can be regulated, including processes such as the establishment and maintenance of stem cell niches, branch- ing morphogenesis, angiogenesis, bone remodeling, and wound repair. In contrast, abnor- mal ECM dynamics lead to deregulated cell proliferation and invasion, failure of cell death, and loss of cell differentiation, resulting in congenital defects and pathological processes including tissue fibrosis and cancer. Understanding the mechanisms of ECM remodeling and its regulation, therefore, is essential for developing new therapeutic inter- ventions for diseases and novel strategies for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. he extracellular matrix (ECM) forms a milieu versatile and performs many functions in addi- Tsurrounding cells that reciprocally influ- tion to its structural role. -

Immune Clearance of Senescent Cells to Combat Ageing and Chronic Diseases

cells Review Immune Clearance of Senescent Cells to Combat Ageing and Chronic Diseases Ping Song * , Junqing An and Ming-Hui Zou Center for Molecular and Translational Medicine, Georgia State University, 157 Decatur Street SE, Atlanta, GA 30303, USA; [email protected] (J.A.); [email protected] (M.-H.Z.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-404-413-6636 Received: 29 January 2020; Accepted: 5 March 2020; Published: 10 March 2020 Abstract: Senescent cells are generally characterized by permanent cell cycle arrest, metabolic alteration and activation, and apoptotic resistance in multiple organs due to various stressors. Excessive accumulation of senescent cells in numerous tissues leads to multiple chronic diseases, tissue dysfunction, age-related diseases and organ ageing. Immune cells can remove senescent cells. Immunaging or impaired innate and adaptive immune responses by senescent cells result in persistent accumulation of various senescent cells. Although senolytics—drugs that selectively remove senescent cells by inducing their apoptosis—are recent hot topics and are making significant research progress, senescence immunotherapies using immune cell-mediated clearance of senescent cells are emerging and promising strategies to fight ageing and multiple chronic diseases. This short review provides an overview of the research progress to date concerning senescent cell-caused chronic diseases and tissue ageing, as well as the regulation of senescence by small-molecule drugs in clinical trials and different roles and regulation of immune cells in the elimination of senescent cells. Mounting evidence indicates that immunotherapy targeting senescent cells combats ageing and chronic diseases and subsequently extends the healthy lifespan. Keywords: cellular senescence; senescence immunotherapy; ageing; chronic disease; ageing markers 1. -

Collagen in Wound Healing

bioengineering Review Collagen in Wound Healing Shomita S. Mathew-Steiner, Sashwati Roy and Chandan K. Sen * Indiana Center for Regenerative Medicine and Engineering, School of Medicine, Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA; [email protected] (S.S.M.-S.); [email protected] (S.R.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-317-278-2735 Abstract: Normal wound healing progresses through inflammatory, proliferative and remodeling phases in response to tissue injury. Collagen, a key component of the extracellular matrix, plays critical roles in the regulation of the phases of wound healing either in its native, fibrillar conformation or as soluble components in the wound milieu. Impairments in any of these phases stall the wound in a chronic, non-healing state that typically requires some form of intervention to guide the process back to completion. Key factors in the hostile environment of a chronic wound are persistent inflammation, increased destruction of ECM components caused by elevated metalloproteinases and other enzymes and improper activation of soluble mediators of the wound healing process. Collagen, being central in the regulation of several of these processes, has been utilized as an adjunct wound therapy to promote healing. In this work the significance of collagen in different biological processes relevant to wound healing are reviewed and a summary of the current literature on the use of collagen-based products in wound care is provided. Keywords: extracellular matrix; collagen; signaling; inflammation; wound healing; collagen dressings; engineered collagen Citation: Mathew-Steiner, S.S.; Roy, S.; Sen, C.K. Collagen in Wound 1. Introduction Healing. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 63. Sophisticated regulation by a number of key factors including the environment of the https://doi.org/10.3390/ wound which is rich in extracellular matrix (ECM) drives the process of wound healing [1,2]. -

Tissue Examination to Monitor Antiangiogenic Therapy: a Phase I Clinical Trial with Endostatin1

3366 Vol. 7, 3366–3374, November 2001 Clinical Cancer Research Tissue Examination to Monitor Antiangiogenic Therapy: A Phase I Clinical Trial with Endostatin1 Christoph Mundhenke, James P. Thomas, INTRODUCTION George Wilding, Fred T. Lee, Fred Kelzc, Neoplasms depend on the formation of new of blood Rick Chappell, Rosemary Neider, vessels (angiogenesis) for continued growth and metastatic Linda A. Sebree, and Andreas Friedl2 spread. Without angiogenesis, tumors remain small and do not threaten the life of the host (1). In normal resting tissues, Comprehensive Cancer Center [C. M., J. P. T., G. W., F. T. L., F. K., R. C., R. N., A. F.], Department of Pathology and Laboratory where blood vessel growth is minimal, angiogenesis is con- Medicine [L. A. S., A. F.], and Department of Biostatistics [R. C.], trolled by a balance of angiogenic stimulators and inhibitors. University of Wisconsin Madison, Wisconsin 53792; and Department This balance is perturbed in tumors to favor angiogenesis of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Kiel, 24105 Germany either by overproduction of angiogenesis inducers or by lack [C. M.] of inhibitors (2). Recently, several naturally occurring angiogenesis inhibi- ABSTRACT tors have been identified. The most potent inhibitor appears to Purpose: The purpose of this study was to determine the be endostatin, the COOH-terminal proteolytic fragment of the effect of the angiogenesis inhibitor endostatin on blood ves- basement membrane component collagen XVIII (3). In a xeno- sels in tumors and wound sites. transplantation model, endostatin administration leads to pro- Experimental Design: In a Phase I dose escalation study, nounced tumor regression, suggesting that the peptide induces cancer patients were treated with daily infusions of human regression of existing blood vessels in addition to preventing the recombinant endostatin.