Memoirs of a Global Hindu a Global Hindu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anthoney Udel 0060D

INCLUSION WITHOUT MODERATION: POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND DEMOCRATIC PARTICIPATION BY RELIGIOUS GROUPS by Cheryl Mariani Anthoney A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science and International Relations Spring 2018 © 2018 Cheryl Anthoney All Rights Reserved INCLUSION WITHOUT MODERATION: POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND DEMOCRATIC PARTICIPATION BY RELIGIOUS GROUPS by Cheryl Mariani Anthoney Approved: __________________________________________________________ David P. Redlawsk, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Political Science and International Relations Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ Ann L. Ardis, Ph.D. Senior Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Muqtedar Khan, Ph.D. Professor in charge of dissertation I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Stuart Kaufman, -

Secrets of RSS

Secrets of RSS DEMYSTIFYING THE SANGH (The Largest Indian NGO in the World) by Ratan Sharda © Ratan Sharda E-book of second edition released May, 2015 Ratan Sharda, Mumbai, India Email:[email protected]; [email protected] License Notes This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-soldor given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person,please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and didnot purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to yourfavorite ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hardwork of this author. About the Book Narendra Modi, the present Prime Minister of India, is a true blue RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or National Volunteers Organization) swayamsevak or volunteer. More importantly, he is a product of prachaarak system, a unique institution of RSS. More than his election campaigns, his conduct after becoming the Prime Minister really tells us how a responsible RSS worker and prachaarak responds to any responsibility he is entrusted with. His rise is also illustrative example of submission by author in this book that RSS has been able to design a system that can create ‘extraordinary achievers out of ordinary people’. When the first edition of Secrets of RSS was released, air was thick with motivated propaganda about ‘Saffron terror’ and RSS was the favourite whipping boy as the face of ‘Hindu fascism’. Now as the second edition is ready for release, environment has transformed radically. -

From Secular Democracy to Hindu Rashtra Gita Sahgal*

Feminist Dissent Hindutva Past and Present: From Secular Democracy to Hindu Rashtra Gita Sahgal* *Correspondence: secularspaces@ gmail.com Abstract This essay outlines the beginnings of Hindutva, a political movement aimed at establishing rule by the Hindu majority. It describes the origin myths of Aryan supremacy that Hindutva has developed, alongside the campaign to build a temple on the supposed birthplace of Ram, as well as the re-writing of history. These characteristics suggest that it is a far-right fundamentalist movement, in accordance with the definition of fundamentalism proposed by Feminist Dissent. Finally, it outlines Hindutva’s ‘re-imagining’ of Peer review: This article secularism and its violent campaigns against those it labels as ‘outsiders’ has been subject to a double blind peer review to its constructed imaginary of India. process Keywords: Hindutva, fundamentalism, secularism © Copyright: The Hindutva, the fundamentalist political movement of Hinduism, is also a Authors. This article is issued under the terms of foundational movement of the 20th century far right. Unlike its European the Creative Commons Attribution Non- contemporaries in Italy, Spain and Germany, which emerged in the post- Commercial Share Alike License, which permits first World War period and rapidly ascended to power, Hindutva struggled use and redistribution of the work provided that to gain mass acceptance and was held off by mass democratic movements. the original author and source are credited, the The anti-colonial struggle as well as Left, rationalist and feminist work is not used for commercial purposes and movements recognised its dangers and mobilised against it. Their support that any derivative works for anti-fascism abroad and their struggles against British imperialism and are made available under the same license terms. -

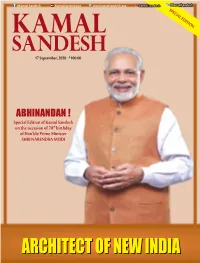

Architect of New India Fortnightly Magazine Editor Prabhat Jha

@Kamal.Sandesh KamalSandeshLive www.kamalsandesh.org kamal.sandesh @KamalSandesh SPECIAL EDITION 17 September, 2020 `100.00 ABHINANDAN ! Special Edition of Kamal Sandesh on the occasion of 70th birthday of Hon’ble Prime Minister SHRI NARENDRA MODI ARCHITECTARCHITECT OFOF NNEWEWArchitect ofII NewNDINDI India KAMAL SANDESHAA 1 Self-reliant India will stand on five Pillars. First Pillar is Economy, an economy that brings Quantum Jump rather than Incremental change. Second Pillar is Infrastructure, an infrastructure that became the identity of modern India. Third Pillar is Our System. A system that is driven by technology which can fulfill the dreams of the 21st century; a system not based on the policy of the past century. Fourth Pillar is Our Demography. Our Vibrant Demography is our strength in the world’s largest democracy, our source of energy for self-reliant India. The fifth pillar is Demand. The cycle of demand & supply chain in our economy is the strength that needs to be harnessed to its full potential. SHRI NARENDRA MODI Hon’ble Prime Minister of India 2 KAMAL SANDESH Architect of New India Fortnightly Magazine Editor Prabhat Jha Executive Editor Dr. Shiv Shakti Bakshi Associate Editors Ram Prasad Tripathy Vikash Anand Creative Editors Vikas Saini Bhola Roy Digital Media Rajeev Kumar Vipul Sharma Subscription & Circulation Satish Kumar E-mail [email protected] [email protected] Phone: 011-23381428, FAX: 011-23387887 Website: www.kamalsandesh.org 04 EDITORIAL 46 2016 - ‘IndIA IS NOT 70 YEARS OLD BUT THIS JOURNEY IS -

Central University of Tamil Nadu, Thiruvarur Provisional Rank List for Mba 2019-2020

CENTRAL UNIVERSITY OF TAMIL NADU, THIRUVARUR PROVISIONAL RANK LIST FOR MBA 2019-2020 Sl. Total No. RegNo RollNo Candidate's Name Father's Name Gender Cateogry Marks 1 PG20071830 21250318 DHARUN KUMAR S V SUGANTHA KUMAR MALE OBC 80.75 2 PG20003887 21762849 DIVEY AGGARWAL MANOJ KUMAR AGGARWAL MALE GENERAL 77.25 3 PG20050626 21602512 ADARSH K CHANDRASEKHARAN MALE OBC 75.25 4 PG20082103 21260583 ABHIJEET BEHERA KAILASH CHANDRA BEHERA MALE GENERAL 74.75 5 PG20029898 21640375 RITESH MAHESHWARI ASHOK MAHESHWARI MALE GENERAL 69.25 6 PG20074285 21461375 HITESH KUMAR SHEESH RAM MALE SC 68.25 7 PG20043176 21240453 SRIRAM ARAVINDH K A KIRUBA SAMUTHERAM R MALE GENERAL 66.50 8 PG20025966 21431213 BILLA RAJASHEKAR KUMARA SWAMY MALE OBC 65.50 9 PG20050389 21240445 R ROHIT VIGNESH M RAVIKUMAR MALE SC 63.00 10 PG20029793 22020306 MANGIRI YOGANJANEYULU MANGIRI RAMANAIAH MALE OBC 62.75 11 PG20044772 21561035 SARATHVARMA T V VASUDEVA VARMA MALE GENERAL 62.50 12 PG20004194 21462241 ARCHANA PAREEK ASHOK PAREEK FEMALE GENERAL 61.75 13 PG20033876 21762865 MIHIR GUPTA KAUSHAL KUMAR MALE OBC 61.50 14 PG20045849 21430543 PADMA HARI KRISHNA PADMA VENKAT NARAYANA MALE OBC 61.25 15 PG20012063 21240335 C YESHWANTH C VENKATESH MALE GENERAL 61.25 16 PG20031038 21790652 CHANDRA BHUSHAN RAM NANDAN SINGH MALE GENERAL 61.00 17 PG20010511 21762852 RISHABH MITTAL RUPESH MITTAL MALE GENERAL 61.00 18 PG20065996 21240079 GOKUL KHANNA P U UDAYA SANKAR P M MALE EWS 60.25 19 PG20000274 21600411 FATHIMA SAMEENA HAROON FASAL PC FEMALE OBC 60.25 20 PG20019922 21501207 PRADYUMNA MOGRE -

Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2010 Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Nandrajog, Elaisha, "Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010)" (2010). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 219. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/219 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE HINDUTVA AND ANTI-MUSLIM COMMUNAL VIOLENCE IN INDIA UNDER THE BHARATIYA JANATA PARTY (1990-2010) SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR RODERIC CAMP AND PROFESSOR GASTÓN ESPINOSA AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY ELAISHA NANDRAJOG FOR SENIOR THESIS (Spring 2010) APRIL 26, 2010 2 CONTENTS Preface 02 List of Abbreviations 03 Timeline 04 Introduction 07 Chapter 1 13 Origins of Hindutva Chapter 2 41 Setting the Stage: Precursors to the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 3 60 Bharat : The India of the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 4 97 Mosque or Temple? The Babri Masjid-Ramjanmabhoomi Dispute Chapter 5 122 Modi and his Muslims: The Gujarat Carnage Chapter 6 151 Legalizing Communalism: Prevention of Terrorist Activities Act (2002) Conclusion 166 Appendix 180 Glossary 185 Bibliography 188 3 PREFACE This thesis assesses the manner in which India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has emerged as the political face of Hindutva, or Hindu ethno-cultural nationalism. The insights of scholars like Christophe Jaffrelot, Ashish Nandy, Thomas Blom Hansen, Ram Puniyani, Badri Narayan, and Chetan Bhatt have been instrumental in furthering my understanding of the manifold elements of Hindutva ideology. -

Indresh Kumar Had Given All Co-Operation to the CBI : Dr. Vaidya by : INVC Team Published on : 12 Mar, 2011 12:51 AM IST

Indresh Kumar had given all co-operation to the CBI : Dr. Vaidya By : INVC Team Published On : 12 Mar, 2011 12:51 AM IST INVC,, Puttur, RSS national annual meet Akhil Bharatiya Pratinidhi Sabha (ABPS) was inaugurated today morning at Vivekananda College Premises, Puttur. Mohanji Bhagwat, Sarasanghachalak, lighted the traditional lamp as well as unfurled the coconut flower as part of the local tradition. Vedic chanting along with traditional panchavadyam were resounding the premises. Mr Suresh Joshi, Sarakaryavah was also present in Dias. Around 1400 delegates from across the country are participating in this 3-day annual meet. Office bearers of various organisations inspired by Sangh including VHP, Bharateeya Kisan Sangh which works among farmers, Vanavasi Kalyan Ashram – a tribal welfare organization; Akhil Bharateeya Vidyarthi Parishad – one of the biggest students’ organization in the country; Bharateeya Mazdoor Sangh – a leading trade union; Bharatiya Janata Party – one of the leading nationalistic political party of Bharat are in attendance. This apart, Office bearers of Vidhya Bharati, Vijnana Bharati, Kreeda Bharati, Seva Bharati, Samskrit Bharati, Samskar Bharati, Laghu Udyog Bharati as well as leaders from Rashtra Sevika Samithi, Swadeshi Jagaran Manch, Deendayal Samshodhan Samsthan, Bharat Vikas Parishad, Shaikshanika Mahasangh, Dharma Jagaran are also part of the conclave. Organizations which focuses on special issues like – Sakshama which works among the blind; Seema Suraksha Parishat – commitedly working among the people of border districts of our country in boosting their confidence, Poorva Sainik Parishat – working among the retired soldiers are also representing. All these organizations will present a report of their activities and their progress. State-wise activities of the RSS will also be reviewed. -

In Bad Faith? British Charity and Hindu Extremism

“I recognized two people pulling away my daughter Shabana. My daughter was screaming in pain asking the men to leave her alone. My mind was seething with fear and fury. I could do nothing to help my daughter from being assaulted sexually and tortured to death. My daughter was like a flower, still to see life.Why did they have to do this to her? What kind of men are these? The monsters tore my beloved daughter to pieces.” Medina Mustafa Ismail Sheikh, then in Kalol refugee camp, Panchmahals District, Gujarat This report is dedicated to the hundreds of thousands of Indians who have lost their homes, their loved ones or their lives because of the politics of hatred.We stand by those in India struggling for justice, and for a secular, democratic and tolerant future. 2 IN BAD FAITH? BRITISH CHARITY AND HINDU EXTREMISM INFORMATION FOR READERS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A separate report summary is available from Any final conclusions of fact or expressions of www.awaazsaw.org. Each section of this opinion are the responsibility of Awaaz – South report also begins with a summary of main Asia Watch Limited alone. Awaaz – South Asia findings. Watch would like to thank numerous individuals and organizations in the UK, India and the US for Section 1 provides brief information on advice and assistance in the preparation of this Hindutva and shows Sewa International UK’s report. Awaaz – South Asia Watch would also like connections with the RSS. Readers familiar to acknowledge the insights of the report The with these areas can skip to: Foreign Exchange of Hate researched by groups in the US. -

Kirpal-Singh-The-Jap-Ji.Pdf

INTRODUCTION Kirpal Singh, California, 1963 THE JAP JI INTRODUCTION THE JAP JI By Krpal Sngh “Man’s only duty is to be ever grateful to God for His innumerable gifts and blessings.” THE JAP JI about the translator . Krpal Sngh, a modern Sant n the drect lne of Guru Nanak, was born n 1894 n the Punjab n Inda (now part of Pakstan). Hs long lfe, saturated wth love for God and humanity, brought peace and fulfillment to approximately 120,000 dscples, scattered all over the world. He taught the natural way to find God while living; and His life was the embodment of Hs teachngs. He made three world tours, was Presdent of the World Fellowshp of Relgons for four- teen years, and convened the World Conference on Unty of Man n February 1974, attended by relgous, socal and poltcal leaders from all over the world. He ded on August 21, 1974, in his eighty-first year, stepping out of his body in full consciousness; His last words were of love for His dis- cples. Hs lfe bears eloquent testmony that the age of the prophets is not over; that it is still possible for human beings to find God and reflect His will. v v INTRODUCTION THE JAP JI The Message of Guru Nanak Literal Translation from the Original Punjabi Text with Introduction, Commentary, Notes, and a Biographical Study of Guru Nanak By Krpal Sngh A RUHANI SATSANG® BOOK RUHANI SATSANG DIVINE SCIENCE OF THE SOUL v v THE JAP JI I have written books without any copyright—no rights reserved — because it is a Gift of God, given by God, as much as sunlight; other gifts of God are also free. -

![UZR W]Zvd $*# ^`Cv E` Wcvvu`^](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8533/uzr-w-zvd-cv-e-wcvvu-848533.webp)

UZR W]Zvd $*# ^`Cv E` Wcvvu`^

* + 7!4 8 5 ( 5 5 VRGR '%&((!1#VCEB R BP A"'!#$#1!$"$#$%T utqBVQWBuxy( (*+,(-'./ ,2,23 0,-1$( ,-./ 31<O62!12!&/$.& @ /< '% 261&$/$ 42/1$/%-; <3 .1<&/.1%.& 23&6 %2 /$!-< 26-$&/ 6& -1$6&$%6 -1& 4$&61 31&!$!12$6-624<@ &$6/$ 2!<12/$ 2>&-%&!$< $2</4.=?- 4216&4% 1=426&.&4>$'&=3&4& / - !$%&' (() *99 :& (2 & 0 1&0121'3'1& " # $ 2342/1$ 2342/1$ s the new I-T portal con- tepping up efforts to bring its Atinued to have glitches and Scitizens back home, India on remained unavailable for two Sunday airlifted 392 people, consecutive days, the Finance besides some Afghan politi- Ministry “summoned” Infosys cians, from Kabul to New Delhi. 2342/1$ MD and CEO Salil Parekh on They were evacuated in three Monday to explain to Finance different flights of the Indian mid the Afghanistan crisis Minister Nirmala Sitharaman Air Force (IAF) and Air India. Aand India’s ongoing evac- the reasons for the continued Some more flights are planned uation exercise following the snags even after over two in the days to come to safely Taliban takeover of the coun- months of the site’s launch. bring back stranded Indian cit- try, Union Housing and Urban However, just ahead of the izens from Afghanistan. Affairs Minister Hardeep Singh meeting with Sitharaman, A team of Indian officials Puri on Sunday cited the evac- Infosys late on Sunday night is now based in Kabul to assist uations from Afghanistan to said that emergency mainte- those Indians who want to back the controversial nance on the website had been return home. -

The Five Dacoits the Five Perversions of Mind from the Path of the Masters by Julian Johnson Sant Kirpal Singh Ji, Hazur Baba Sawan Singh Ji, and Others

The Five Dacoits The Five Perversions of Mind From The Path of the Masters by Julian Johnson Sant Kirpal Singh Ji, Hazur Baba Sawan Singh Ji, and others We are constantly beset by five foes - passion, anger, greed, worldly attachments, and vanity. All these must be mastered, brought under control. You can never do that entirely until you have the aid of the Guru and are in harmonic relations with the Sound Current. But you can begin now, and every effort will be a step on the way. (Baba Sawan Singh, Spiritual Gems, 339) Swami Ji has said that we should not hesitate to go all out to still the mind. We do not fully grasp that the mind takes everyone to his doom. It is like a thousand-faced snake, which is constantly with each being; it has a thousand different ways of destroying the person. The rich with riches, the poor with poverty, the orator with his fine speeches – it takes the weakness in each and plays upon it to destroy him. (Sant Kirpal Singh Ji) ruhanisatsangusa.org/serpent.htm Contents Page: 1. The Five Perversions of Mind, from The Path of the Masters, by Julian Johnson 2. Biography of Julian Johnson, from Wikipedia 3. Lust– Julian Johnson 5. The Case for Chastity, Parts 1 & 2 from Sat Sandesh 6. Sant Kirpal Singh Ji on Chastity 7. Hazur Baba Sawan Singh 8. Anger– Julian Johnson 10. Anger Quotes 11. Sant Kirpal Singh on Anger 12. Baba Sawan Singh, Jack Kornfield 13. Greed– Julian Johnson 14. Greed Quotes 15. -

Nationalist Pursuit Nationalist Pursuit

NATIONALIST PURSUIT NATIONALIST PURSUIT LECTURES BY DATTOPANT THEN&ADI English Rendering by M. K. alias BHAUSAHEB PARANJAPE and SUDHAKAR RAJE SAHITYA SINDHU PRAKASHANA, BANGALORE, INDIA NATIONALIST PURSUIT. By DATTOPANT THENGADI. Translated from Hindi by M. K. alias BHAUSAHEB PARANJAPE and SUDHAKAR RAJE. Originally published as Sanket Rekha in Hindi. Lectures dealing with the roots of nationalism, preconditions for social harmony and all-round national reconstruction, and exploration of alternatives to present structures. Pages : xii + 300. 1992 Published by : SAHITYA SINDHU PRAKASHANA Rashtrotthana Building Complex Nrupatunga Road BANGALORE - 560 002 (India) Typeset by Bali Printers, Bangalore - 560 002 Printed at Rashtrotthana M udranalaya, Bangalore - 560 019 PUBLISHERS’ PREFACE We consider it a rare privilege and honour to be able to bring out this collection of lectures by Shri Dattopant Thengadi who has distin guished himself as a front-rank thinker and social worker of long stand ing. There is hardly any aspect of public life which has not engaged his attention at one time or another. A remarkable feature of his personality is that though incessantly occupied with intense organisational activity he has never distanced himself from intellectual endeavour. Vast is his erudition ; and it is the objective and comprehensive perspective bom out of this intrinsic nature which has in no small measure contributed to the progress of the various organisations founded and nurtured by him which include the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh, the Bharatiya Kisan Sangh and the Samajik Samarasata Manch. Shri Thengadi has been a prolific writer, with over a hundred books, booklets and articles in English, Hindi and Marathi to his credit.