Economic and Social Council

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chimpanzees ( Pan Troglodytes Verus ) and Ful Ɓe Pastoralists

Predicting conflict over scarce resources: Chimpanzees ( Pan troglodytes verus ) and Ful ɓe pastoralists by Brooke E. Massa Dr. Jennifer Swenson, Advisor May 2011 Masters project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Environmental Management degree in the Nicholas School of the Environment of Duke University 2011 MP Advisor's signature Cover photo: A pruned Khaya senegalensis tree stands, surrounded by its cut branches. Also known as African mahogany , the tree is prized not only for the fodder it provides, but also as a strong wood, often used to craft farming tools. Khaya senegalensis is considered a vulnerable species by the IUCN and is protected by several West African governments. 2 Abstract The western chimpanzee ( Pan troglodytes verus ) is considered the most endangered subspecies of chimpanzee. The populations living at the furthest extent of its range, in southern Senegal – a country situated directly south of the Sahara Desert - are considered to be nearly extinct. These ‘savanna chimpanzees’ have adapted to living in an arid environment and are now facing more threats to their survival as climate change and deforestation have forced nomadic pastoralists further into their habitat in search of fodder and water. Combining field-collected data on both chimpanzee and pastoralist habitat use with GIS and remote sensing data, I spatially predicted areas of potential habitat conflict among chimpanzees and pastoralists. Using species distribution modeling, I found that large swaths of forested habitat in Bandafassi are predicted to be used by nomadic pastoralists. Their presence is expected in 86 percent of the land which is predicted to be used by chimpanzees. -

Extensions of Remarks

April 26, 1990 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 8535 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS BENEFITS OF AUTOMATION First-class mail delivery performance was "The mail is not coming in here so we ELUDE POSTAL SERVICE at a five-year low last year, and complaints have to slow down," to avoid looking idle, about late mail rose last summer by 35 per said C. J. Roux, a postal clerk. "We don't cent, despite a sluggish 1 percent growth in want to work ourselves out of a job." HON. NEWT GINGRICH mall volume. The transfer infuriated some longtime OF GEORGIA Automation was to be the service's hope employees, who had thought that they IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES for a turnaround. But efforts to automate would be protected in desirable jobs because have been plagued by poor management and of their seniority. Thursday, April 26, 1990 planning, costly changes of direction, inter "They shuffled me away like an old piece Mr. GINGRICH. Mr. Speaker, as we look at nal scandal and an inability to achieve the of furniture," said Alvin Coulon, a 27-year the Postal Service's proposals to raise rates paramount goal of moving the mall with veteran of the post office and one of those and cut services, I would encourage my col fewer people. transferred to the midnight shift in New Or With 822 new sorting machines like the leans. "No body knew nothing" about the leagues to read the attached article from the one in New Orleans installed across the Washington Post on the problems of innova change. "Nobody can do nothing about it," country in the last two years, the post of he said. -

Steering the Ark Toward Eden: Design for Animal Well-Being

awf03.qxd 9/10/2003 1:50 PM Page 977 48. Terio KS, Munson L. Gastritis in cheetahs and relatedness to 49. Wielebnowski NC, Fletchall N, Carlstead K, et al. Non- adrenal function. In: Pukazhenthi B, Wildt D, Mellen J, eds. Felid invasive assessment of adrenal activity associated with husbandry taxon advisory group action plan. Report. Columbia, SC: American and behavioral factors in the North American clouded leopard pop- Zoo and Aquarium Association 2000;36. ulation. Zoo Biol 2002;21:77–98. Steering the ark toward Eden: design for animal well-being Jon Charles Coe, MLA, FASLA hatever one thinks of capturing wild animals for Larger, lushly landscaped displays modeled on Wpets, zoos, aquariums, or research, one may also natural habitats emerged in the United States in the think of their descendants as refugees of our own 1970s. My recollection of the period was that the same species’ global war for dominion over nature. This sentiment, which favored nature as the model in dis- paper will review the development of zoo design as we play design, favored a more hands-off policy in hus- seek to improve the well-being of these zoologic bandry. Gone were chimpanzee tea parties. Gone also refugees. were mechanical mice as enrichment stimuli. Naturalistic displays were thought by some to be suffi- Stage 1—Physical Survival ciently stimulating that additional stimulation was During the era of barred cages, there were few unnecessary.3 While this approach worked well, it did long-term survivors. Advances in diet and veterinary not always prevent problems, such as loss of occupa- care brought in the era of green-tile enclosures and, for tion. -

Laboratory Primate Newsletter

LABORATORY PRIMATE NEWSLETTER Vol. 42, No. 2 April 2003 JUDITH E. SCHRIER, EDITOR JAMES S. HARPER, GORDON J. HANKINSON AND LARRY HULSEBOS, ASSOCIATE EDITORS MORRIS L. POVAR, CONSULTING EDITOR ELVA MATHIESEN, ASSISTANT EDITOR ALLAN M. SCHRIER, FOUNDING EDITOR, 1962-1987 Published Quarterly by the Schrier Research Laboratory Psychology Department, Brown University Providence, Rhode Island ISSN 0023-6861 POLICY STATEMENT The Laboratory Primate Newsletter provides a central source of information about nonhuman primates and re- lated matters to scientists who use these animals in their research and those whose work supports such research. The Newsletter (1) provides information on care and breeding of nonhuman primates for laboratory research, (2) dis- seminates general information and news about the world of primate research (such as announcements of meetings, research projects, sources of information, nomenclature changes), (3) helps meet the special research needs of indi- vidual investigators by publishing requests for research material or for information related to specific research prob- lems, and (4) serves the cause of conservation of nonhuman primates by publishing information on that topic. As a rule, research articles or summaries accepted for the Newsletter have some practical implications or provide general information likely to be of interest to investigators in a variety of areas of primate research. However, special consid- eration will be given to articles containing data on primates not conveniently publishable elsewhere. General descrip- tions of current research projects on primates will also be welcome. The Newsletter appears quarterly and is intended primarily for persons doing research with nonhuman primates. Back issues may be purchased for $5.00 each. -

List of Suppliers As of January 21, 2020

List of Suppliers as of January 21, 2020 1006547746 1 800 WINE SHOPCOM INC 525 AIRPARK RD NAPA CA 945587514 7072530200 1018334858 1 SPIRIT 3830 VALLEY CENTRE DR # 705-903 SAN DIEGO CA 921303320 8586779373 1017328129 10 BARREL BREWING CO 62970 18TH ST BEND OR 977019847 5415851007 1018691812 10 BARREL BREWING IDAHO LLC 826 W BANNOCK ST BOISE ID 837025857 5415851007 1017363560 10TH MOUNTAIN WHISKEY AND SPIRITS COMPANY LLC 500 TRAIL GULCH RD GYPSUM CO 81637 9703313402 1001989813 14 HANDS WINERY 660 FRONTIER RD PROSSER WA 993505507 4254881133 1035490358 1849 WINE COMPANY 4441 S DOWNEY RD VERNON CA 900582518 8185813663 1040236189 2 BAR SPIRITS 2960 4TH AVE S STE 106 SEATTLE WA 981341203 2064024340 1017669627 2 TOWNS CIDERHOUSE 33930SE EASTGATE CIR CORVALLIS OR 97333 5412073915 1006562982 21ST CENTURY SPIRITS 6560 E WASHINGTON BLVD LOS ANGELES CA 900401822 1040807186 2HAWK VINEYARD AND WINERY 2335 N PHOENIX RD MEDFORD OR 975049266 5417799463 1008951900 3 BADGE MIXOLOGY 32 PATTEN ST SONOMA CA 954766727 7079968463 1016333536 3 CROWNS DISTRIBUTORS 534 MONTGOMERY AVE STE 202 OXNARD CA 930360815 8057972127 1040217257 3FWINE LLC 21995 SW FINNIGAN HILL RD HILLSBORO OR 971238828 5035363083 1038066492 8 BIT BREWING COMPANY 26755 JEFFERSON AVE STE F MURRIETA CA 925626941 9516772322 1014665400 8 VINI INC 1250 BUSINESS CENTER DR SAN LEANDRO CA 945772241 5106758888 1041559577 88 EAST BEVERAGE COMPANY 533 N MARSHFIELD AVE CHICAGO IL 606226315 6308624697 1015273823 90+ CELLARS 84 CALVERT ST STE 1G HARRISON NY 105283240 7075288500 1040525121 A & M WINE & SPIRITS -

Access to Finance Forum in the Democratic Republic of Congo

Access to Finance Forum in the Democratic Republic of Congo EXPERIENCES FROM FINANCIAL COOPERATION Impressum: Published by KfW Bankengruppe Communication Department Palmengartenstr. 5-9 60325 Frankfurt am Main Germany Phone +49 (0) 69 7431-0 Fax +49 (0) 69 7431-2944 www.kfw.de Author RDC Entreprises Développement - Programme TPE de CECFOR Marie-Hélène Brasey [email protected] Avenue Kimenza 62 Commune de Kasa Vubu Kinshasa Democratic Republic of Congo www.iecd.org On behalf of KfW Entwicklungsbank Competency Center for Financial and Private Sector Development Photos: Marie-Hélène Brasey Frankfurt am Main, November 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents.......................................................................................................................1 1. Summary................................................................................................................................2 2. Conceptual and methodological approach.............................................................................3 2.1 General background.........................................................................................................3 2.2. Methodology....................................................................................................................4 3. Preparation for the event........................................................................................................6 3.1 Design and production of communication aids.................................................................6 -

Notice of Regular Meeting Of

Orange County Mosquito and Vector Control District Serving Orange County Since 1947 BUILDING, PROPERTY AND EQUIPMENT COMMITTEE MEETING AT 1:00 PM POLICY AND PERSONNEL COMMITTEE MEETING AT 1:30 PM BUDGET AND FINANCE COMMITTEE MEETING AT 2:00 PM NOTICE AND AGENDA OF THE REGULAR MEETING OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES THURSDAY NOVEMBER 15, 2018 864TH REGULAR MEETING 3:00 P.M. 13001 GARDEN GROVE BLVD. GARDEN GROVE, CA 92843 WEBSITE ADDRESS: www.ocvector.org REGULAR MEETING 3:00 P.M. A. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE, ROLL CALL, AND LATE COMMUNICATIONS 1. Call business meeting to order 3:00 p.m. 2. Pledge of Allegiance 3. Roll Call - (If absences occur, consider whether to deem those absences excused based on facts presented for the absence — such determination shall be the permission required by law.) PRESIDENT: Lucille Kring Anaheim VICE-PRESIDENT: Cheryl Brothers Fountain Valley SECRETARY: Shari Horne Laguna Woods Aliso Viejo Phillip Tsunoda Lake Forest Bob Holtzclaw Anaheim Lucille Kring Los Alamitos Mark Chirco Brea Cecilia Hupp Mission Viejo Bob Ruesch Buena Park Michael Davis Newport Beach Scott Peotter Costa Mesa Sandra Genis Orange Michael Alvarez Cypress Paulo Morales Placentia Craig Green Dana Point Richard Viczorek Rancho Santa Margarita April Josephson Fountain Valley Cheryl Brothers San Clemente Michelle Schumacher Fullerton Jennifer Fitzgerald San Juan Capistrano Pam Patterson Garden Grove Stephanie Klopfenstein Santa Ana Cecilia Aguinaga Huntington Beach Mike Posey Seal Beach Sandra Massa-Lavitt Irvine Lynn Schott Stanton Al Ethans La Habra James Gomez Tustin Letitia Clark La Palma Marshall Goodman Villa Park Bill Nelson Laguna Beach Rob Zur Schmiede Westminster Sergio Contreras Laguna Hills Larry Woodruff Yorba Linda Peggy Huang Laguna Niguel John Mark Jennings County of Orange Lilly Simmering Laguna Woods Shari Horne 4. -

Zenker, Stephanie F., Ed. Books For

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 415 506 CS 216 144 AUTHOR Stover, Lois T., Ed.; Zenker, Stephanie F., Ed. TITLE Books for You: An Annotated Booklist for Senior High. Thirteenth Edition. NCTE Bibliography Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-0368-5 ISSN ISSN-1051-4740 PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 465p.; For the 1995 edition, see ED 384 916. Foreword by Chris Crutcher. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 03685: $16.95 members, $22.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC19 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; Adolescents; Annotated Bibliographies; *Fiction; High School Students; High Schools; *Independent Reading; *Nonfiction; *Reading Interests; *Reading Material Selection; Reading Motivation; Recreational Reading; Thematic Approach IDENTIFIERS Multicultural Materials; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Designed to help teachers, students, and parents identify engaging and insightful books for young adults, this book presents annotations of over 1,400 books published between 1994 and 1996. The book begins with a foreword by young adult author, Chris Crutcher, a former reluctant high school reader, that discusses what books have meant to him. Annotations in the book are grouped by subject into 40 thematic chapters, including "Adventure and Survival"; "Animals and Pets"; "Classics"; "Death and Dying"; "Fantasy"; "Horror"; "Human Rights"; "Poetry and Drama"; "Romance"; "Science Fiction"; "War"; and "Westerns and the Old West." Annotations in the book provide full bibliographic information, a concise summary, notations identifying world literature, multicultural, and easy reading title, and notations about any awards the book has won. -

Cheetah Conservation Fund Newsletter

Number 20 May 2004 CHEETAH CONSERVATION FUND NEWSLETTER PO BOX 1755 OTJIWARONGO, NAMIBIA WWW. CHEETAH. ORG CHEETA@ IAFRICA. COM. NA Marker visits Iran for Asiatic Cheetah Workshop IRAN BY bonnie schumann CCF Staff Member What do Iranian goat herders and Na- mibian cattle farmers have in common? Why, cheetahs, of course! From Otjiwarongo cattle country to the dusty plains of Iran, cattle farmers and goat herd- ers grapple with the age-old conflict that has been raging between livestock-owning humans and meat-hungry predators. Namibia is the undisputed cheetah capi- tal of the world, while Iran is home to the last remaining free-ranging cheetah outside Africa, thought to number no more than 100 individu- als. ASIATIC CHEETAH: Dr. Laurie Marker, the Cheetah Conser- There are now only fewer than 100 vation Fund (CCF) executive director, under- surviving cheetah in Iran took the long journey to Iran to participate in an International Workshop on the Conservation of The remaining Asiatic Cheetah are found the Asiatic Cheetah. Marker met with Iranian DR.LAURIE MARKER IN IRAN WITH A on the edge of Dasht-e Kavir – a large area government officials, conservationists (from of desert and shrub steppe, which is the last LOCAL IRANIAN HERDER. around the world), Iranian camel herders and stronghold of the Cheetah in Asia smallstock owners to seek solution to the prob- Main threats to the survival of the Asiatic lems facing the Iranian farmers and the last few tus of the species and plan long-term conserva- Cheetah are habitat disturbance and representatives of the Asiatic cheetah. -

Saint Louis Zoo 2015 Annual Report

This year’s annual report highlights the strength of our community support. Our Zoo donors, sponsors, staff and volunteers continue to outdo themselves to help make us a world-class zoo. A special note of thanks is in order, perhaps by postcard or Zoo Mail! Either way, we appreciate all that you do. F. Holmes Lamoreux Jeffrey P. Bonner, Ph.D. Chair, St. Louis Zoological Park Dana Brown President & CEO Subdistrict Commission 1 Kali the polar bear is in our care at the Saint Louis Zoo, and we couldn’t be more excited. In 2010, the Zoo announced The Living Promise Kali (pronounced “Cully”) is the first bear in the Campaign to garner support for the Zoo in four new space. He’s a three and a half year-old male important areas: creating dynamic exhibits, polar bear who had been orphaned in Alaska. In enhancing the visitor experience, modernizing March 2013, he was turned over to U.S. Fish & our facilities and endowing the Zoo’s future. Wildlife Service (USFWS) by an Alaska Native hunter who killed Kali’s mother in a subsistence In 2015, the innovative McDonnell Polar Bear hunt without realizing the mother had a cub. Point exhibit opened. The new habitat is USFWS determined that St. Louis would be particularly important, considering polar bears the bear’s permanent home, working with the have become a conservation priority. The Association of Zoos and Aquariums’ Polar Bear 40,000-square-foot McDonnell Polar Bear Species Survival Plan. Point has natural substrate and saltwater pools, giving the space a sea-to-coastline-to-land The $15.7 million McDonnell Polar Bear Point effect. -

Giant and Dwarf

Juraj Mesík Giant and Dwarf “New Europeans” and Perspectives of Africa Juraj Mesík was involved in ecological issues for many years; first as consultant for the then Czechoslovak Minister of the Environment and later as director of the Ecopolis Foundation. He worked for the World Bank in Washington from 2003 until 2008. Currently, he teaches about global problems and challenges at the Palacký University in the Czech Republic and at the Comenius University in Slovakia. Juraj Mesík Giant and Dwarf “New Europeans” and Perspectives of Africa Giant and Dwarf Juraj Mesík Published by the Pontis Foundation, Bratislava 2013. Edition no. 1 © All rights reserved. ISBN 978-80-971310-0-5 This publication was produced within the Knowledge Makes Change! project that is supported by the European Union. The information and views set out in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Union. To my father (1933 – 2011) Contents Preface ...........................................................................................................................................................7 Why Should We Be Interested in Africa? ....................................................................................................9 SECTION ONE: CONTINENT OF GIGANTIC PROBLEMS Population Growth: A Thorn in Africa’s side ............................................................................................ 16 Could Malthus Be Right? Memento from St. Matthew’s Island ...............................................................25 -

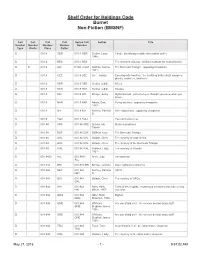

Shelf Order for Holdings Code Burnet Non-Fiction (BMSNF)

Shelf Order for Holdings Code Burnet Non-Fiction (BMSNF) Call Call Call Call Sorted Call Author Title Number Number Number Number Number Type Prefix Class Cutter D 001.4 GER 001.4 GER Gerber, Larry, Cited! : identifying credible information online 1946- D 001.4 RES 001.4 RES The research virtuoso : brilliant methods for normal brains D R 001.9 Gaf R 001.9 Gaf Gaffron, Norma, The Bermuda Triangle : opposing viewpoints 1931- D 001.9 GEE 001.9 GEE Gee, Joshua Encyclopedia horrifica : the terrifying truth! about vampires, ghosts, monsters, and more D 001.9 HER 001.9 HER Herbst, Judith. Aliens D 001.9 HER 001.9 HER Herbst, Judith. Hoaxes D 001.9 KRI 001.9 KRI Krieger, Emily Myths busted! : just when you thought you knew what you knew-- D 001.9 NAR 001.9 NAR Nardo, Don, Flying saucers : opposing viewpoints 1947- D 001.9 Net 001.9 Net Netzley, Patricia Alien abductions : opposing viewpoints D. D 001.9 YOU 001.9 YOU You can't scare me!. D 001.94 ANS 001.94 ANS Ansary, Mir Mysterious places Tamim D 001.94 DUF 001.94 DUF Duffield, Katy The Bermuda Triangle D 001.94 OXL 001.94 OXL Oxlade, Chris The mystery of crop circles D 001.94 OXL 001.94 OXL Oxlade, Chris The mystery of the Bermuda Triangle D 001.94 WAL 001.94 WAL Wallace, Holly, The mystery of Atlantis 1961- D 001.9403 ALL 001.9403 Allen, Judy Unexplained ALL D 001.942 BRI 001.942 BRI Bringle, Jennifer Alien sightings in America D 001.942 NET 001.942 Netzley, Patricia UFO's NET D.