ALABAMA University Libraries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOG SPIDERS Written by Ammon Gilbert from A

DOG SPIDERS Written by Ammon Gilbert From a Concept by Ammon Gilbert, Jim Law, and Johnny Moreno © BingeMedia 1 We open up the movie in a science lab, and not just any science lab, but something out of THE AMAZING SPIDER - MAN (that's for you Law, no w shut your mouth), something that's filled with lab coats, beakers, and fancy high - tech equipment that nobody really knows how to operate, but goddamn does it look cool. There are various scientists wandering around with clipboards, pocket protectors, thi ck - rimmed glasses, and classic white shin - hanging lab coats. It's a typical day at the ol' science lab doing typical science lab shit. Trotting down one of the many isles like it owns the place is a Golden Retriever. Like many Golden Retriever, this one ha s a perpetual smile on its face and looks about as happy as a pig in shit just being there. We focus on its collar to find its name is GINGER ). Ginger trots down the a isle on its way to its owner, Dr. Jack Hammer. Jack is a regular Rico Suave: handsomely g ood looking with a chiseled chin and a beefed out frame to match (i.e., the perfect role for Paul Logan). He is also sporting a lab coat and thick rimmed glasses because he's a scientist and that's what scientists do. He's currently working on some science shit, pouring liquid into various beakers, analyzing data, and concentrating intensely. Ginger stops trotting and sits by Jack , obviously wanting attention. -

Captain Cosmo's Whizbang Has Finally Made the Big Time with a Real Book Review1n Kilobaud Courtesy Satisfied Reader Larry Stone

CAPTAIN ..COSMO'S WHIZ BANG .. By _Jeff • Duntemann For Me and You and the 1802 I WHAT IS THIS? It's a book, by cracky, about the 1802; hopefully the oddest and most entertaining book on any microprocessor ever written. The 1802 is, after all, an odd and entertaining chip. This view is not shared by all. Physicist Mike Brandl said he could swallow a mouthful of sand and barf up a better microprocessor than the 1802, and another colleague claims its instruction set demands that he program with his left hand. Bitch, bitch, bitch. I kinda like it. Much of this material I.rd oped out while recovering from hernia surgery not long ago and couldn't lift anything heavier than a 40-pin DIP. I had a lot of fun and thought you might like to be copied in on it. Like everything else I do, this book is an experiment. If I don't take a serious loss on production and mailing costs, I may do up another one. I've got a little gimcrack on the bench that'll make you people drool: an easy-to-build thermal printer for the 1802 that you can make for seventy bucks flat with all new parts. I'm working on an automatic phone dialer board and a few other things. Selectric interface. Robotics. Ham radio stuff. All kindsa things. Are you interested? Would you lay out another five beans for a Volume II? Let me know; drop me a note with any and all comments and spare not the spleen; I'm a hard man to offend and I lQ~~ crackpot letters. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Relatório Final

Relatório de Bolsa de Iniciação Científica Relatório Final Número do Processo: 2018/11470-1 Nome do Projeto: Inovação Audiovisual e a Voz Política em Let England Shake, Biophilia e Lemonade Vigência: 01/10/2018 a 30/09/2019 Período coberto pelo relatório: 10/03/2019 - 30/09/2019 Nome do Beneficiário/Bolsista: Fernando Paes de Oliveira Chaves Guimarães Nome do Responsável/Orientador: Cecília Antakly de Mello Fernando Paes de Oliveira Chaves Guimarães Cecília Antakly de Mello b) Resumo do plano inicial e das etapas já descritas em relatórios anteriores O projeto Inovação audiovisual e a voz política em Let England Shake, Biophilia e Lemonade teve como proposição inicial a investigação de novas formas audiovisuais que, de certo modo, são derivadas dos videoclipes e compõem um amálgama entre música e audiovisual. Em um primeiro momento, foi realizada uma extensa pesquisa sobre a história do videoclipe, suas origens e influências formais. Para essa pesquisa, utilizei uma bibliografia extensa, composta por autores como Arlindo Machado, Ken Dancyger, Kristin Thompson e David Bordwell, Flora Correia e Carol Vernallis. A obra Experiencing Music Video, de Carol Vernallis foi muito importante para o desenvolvimento da pesquisa e o uso da reserva técnica da bolsa para a aquisição dessa obra foi fundamental, uma vez que não a encontrei em bibliotecas públicas. Após o levantamento bibliográfico incial, foi realizada uma pesquisa sobre a biografia das artistas, de modo a possibilitar um melhor entendimento do contexto em que cada uma das obras foi lançada e a trajetória das três artistas até o momento de criação dos álbuns. Em seguida, realizei uma análise meticulosa de Let England Shake e Lemonade. -

Narrative Strategies and Music in Visual Albums

Narrative strategies and music in visual albums Lolita Melzer (6032052) Thesis BA Muziekwetenschap MU3V14004 2018-2019, block 4 University of Utrecht Supervisor: dr. Olga Panteleeva Abstract According to E. Ann Kaplan, Andrew Goodwin and Carol Vernallis, music videos usually do not have a narrative, at least not one like in classical Hollywood films. David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson state that such a narrative consists of events that are related by cause and effect and take place in a particular time and place. However, articles about music videos have not adequately addressed a new trend, namely the so called “visual album”. This medium is a combination of film and music video elements. Examples are Beyoncé’s much discussed visual album Lemonade from 2016 and Janelle Monáe’s “emotion picture” Dirty Computer from 2018. These visual albums are called ‘narrative films’ by sites such as The Guardian, Billboard and Vimeo, which raises questions about how narrative works in these media forms, because they include music videos which are usually non-narrative. It also poses the question how music functions with the narrative, as in most Hollywood films the music shifts to the background. By looking at the classical Hollywood narrative strategy and a more common strategy used in music videos, called a thread or motif strategy by Vernallis, I have analysed the two visual albums. After comparing them, it seems that both Lemonade and Dirty Computer make use of the motif strategy, but fail in achieving a fully wrought film narrative. Therefore, a different description to visual albums than ‘narrative film’, could be considered. -

Understanding Black Feminism Through the Lens of Beyoncé’S Pop Culture Performance Kathryn M

Seattle aP cific nivU ersity Digital Commons @ SPU Honors Projects University Scholars Spring June 7th, 2018 I Got Hot Sauce In My Bag: Understanding Black Feminism Through The Lens of Beyoncé’s Pop Culture Performance Kathryn M. Butterworth Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/honorsprojects Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Race, Ethnicity and Post- Colonial Studies Commons Recommended Citation Butterworth, Kathryn M., "I Got Hot Sauce In My Bag: Understanding Black Feminism Through The Lens of Beyoncé’s Pop Culture Performance" (2018). Honors Projects. 81. https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/honorsprojects/81 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the University Scholars at Digital Commons @ SPU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ SPU. I GOT HOT SAUCE IN MY BAG: UNDERSTANDING BLACK FEMINISM THROUGH THE LENS OF BEYONCÉ’S POP CULTURE PREFORMANCE by KATHRYN BUTTERWORTH FACULTY ADVISOR, YELENA BAILEY SECOND READER, CHRISTINE CHANEY A project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the University Scholars Program Seattle Pacific University 2018 Approved_________________________________ Date____________________________________ Abstract In this paper I argue that Beyoncé’s visual album, Lemonade, functions as a textual hybrid between poetry, surrealist aesthetics and popular culture—challenging the accepted understanding of cultural production within academia. Furthermore, Lemonade centers black life while presenting mainstream audiences with poetry and avant-garde imagery that challenge dominant views of black womanhood. Using theorists bell hooks, Stuart Hall, Patricia Hill- Collins and Audre Lorde, among others, I argue that Beyoncé’s work challenges the understanding of artistic production while simultaneously fitting within a long tradition of black feminist cultural production. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

Beyoncé's Lemonade Collaborator Melo-X Gives First Interview on Making of the Album.” Pitchfork, 25 Apr

FACULTADE DE FILOLOXÍA DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOLOXÍA INGLESA GRAO EN INGLÉS: ESTUDOS LINGÜÍSTICOS E LITERARIOS Beyoncé’s Lemonade: “A winner don’t quit” ANDREA PATIÑO DE ARTAZA TFG 2017 Vº Bº COORDINADORA MARÍA FRÍAS RUDOLPHI Table of Contents Abstract 1. Introduction 3 2. Methodology 4 3. Beyonce's Lemonade (2016) 5 3.1 Denial: “Hold Up” 6 3.2 Accountability: “Daddy Lessons” 12 3.3 Hope: “Freedom” 21 3.4 Formation 33 4. Conclusion 44 5. Works Cited 46 Appendix 49 Abstract Beyoncé’s latest album has become an instant social phenomenon worldwide. Given its innovative poetic, visual, musical and socio-politic impact, the famous and controversial African American singer has taken an untraveled road—both personal and professional. The purpose of this essay is to provide a close reading of the poetry, music, lyrics and visuals in four sections from Beyoncé’s critically acclaimed Lemonade (2016). To this end, I have chosen what I believe are the most representative sections of Lemonade together with their respective songs. Thus, I focus on the song “Hold Up” from Denial; “Daddy Lessons” from Accountability, “Freedom” from Hope, and “Formation,” where Beyoncé addresses topics such as infidelity, racism, women’s representation, and racism and inequality. I analyse these topics through a close-reading and interpretation of Warsan Shire’s poetry (a source of inspiration), as well as Beyoncé’s own music, lyrics, and imagery. From this analysis, it is safe to say that Lemonade is a relevant work of art that will perdure in time, since it highlights positive representations of African-Americans, at the same time Beyoncé critically denounces the current racial unrest lived in the USA. -

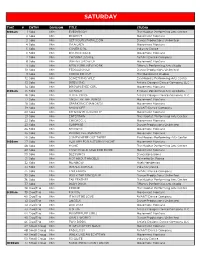

VIRTUAL LINEUP.Xlsx

SATURDAY TIME # ENTRY DIVISION TITLE STUDIO 8:00am 1 Solo Mini EVERYBODY The Habitat Performing Arts Center 2 Solo Mini RESPECT Movement Montana 3 Solo Mini GET YOUR SPARKLE ON Dance Productions Unlimited 4 Solo Mini I'M A LADY Movement Montana 5 Solo Mini COVER GIRL Industry Dance 6 Solo Mini BOUNCE BACK Movement Montana 7 Solo Mini I WANNA DANCE AVANTI Dance Company 8 Solo Mini WHEN I GROW UP Movement Montana 9 Solo Mini NEW YORK, NEW YORK Tiffany's Performing Arts Studio 10 Solo Mini FERGALICIOUS Dance Productions Unlimited 11 Solo Mini CHECK ME OUT The Movement Studios 12 Solo Mini SOMETHING WILD Eva Moore's Performing Arts Center 13 Solo Mini BIRDSONG Artistic Designs Dance Company LLC 14 Solo Mini BROWN EYED GIRL Movement Montana 8:30am 15 Solo Mini GO SOLO 8 Count Performing Arts Academy 16 Solo Mini LITTLE VOICE Artistic Designs Dance Company LLC 17 Solo Mini ANGEL BY THE WINGS Movement Montana 18 Solo Mini SPARKLING DIAMONDS Movement Montana 19 Solo Mini SHOW OFF AVANTI Dance Company 20 Solo Mini MY NEW PHILOSOPHY Movement Montana 21 Solo Mini ENTERTAIN The Habitat Performing Arts Center 22 Solo Mini CHICAGO, IL Movement Montana 23 Solo Mini SURPRISE Dance Productions Unlimited 24 Solo Mini SHOWOFF Movement Montana 25 Solo Mini PAVING THE RUNWAY Movement Montana 26 Solo Mini SOMEWHERE OUT THERE Eva Moore's Performing Arts Center 9:00am 27 Solo Mini LULLABY FOR A STORMY NIGHT Movement Montana 28 Solo Mini HOME The Habitat Performing Arts Center 29 Solo Mini HOW COULD I ASK FOR MORE Movement Montana 30 Solo Mini BLESSINGS DanceXpressions -

Beyoncé, Bella Y Talentosa

Image not found or type unknown www.juventudrebelde.cu Image not found or type unknown Beyoncé Autor: Internet Publicado: 21/09/2017 | 06:38 pm Beyoncé, bella y talentosa El pasado 4 de septiembre, Beyoncé Giselle Knowles-Carter, para todos Beyoncé, arribó a su 35 cumpleaños esta reconocida cantante que saltó a la fama a finales de los 90 Publicado: Lunes 12 septiembre 2016 | 11:02:28 pm. Publicado por: Juventud Rebelde El pasado 4 de septiembre, Beyoncé Giselle Knowles-Carter —para todos Beyoncé— arribó a su 35 cumpleaños. Nacida en Houston, Texas, en 1981, esta reconocida cantante, bailarina, modelo, actriz y empresaria estadounidense se presentó en diversos concursos de canto y baile cuando era niña y saltó a la fama a finales de los 90 como vocalista principal del grupo femenino de R&B, Destiny´s Child, que manejado por su padre, Mathew Knowles, se convirtió en uno de los de su tipo que ha conseguido mayores ventas de la historia. Dangerously In Love (2002) se nombra, por su parte, el álbum debut de Beyoncé, el cual la consagró como artista solista en todo el mundo. Con el vendió 11 millones de copias, ganó cinco premios Grammy, al tiempo que colocó dos de sus sencillos en el número uno del Billboard Hot 100: Crazy in Love y Baby Boy. No obstante, la disolución de Destiny´s Child no ocurrió hasta 2005. Fue entonces cuando la afamada intérprete presentó su segundo disco de estudio, B´Day, que contenía los éxitos Déja Vu, Irreplaceable y Beautiful liar. B´Day salió en 2006, año en que Beyoncé incursionó en el cine, en la película Dreamgirls, con un papel nominado al Globo de Oro. -

Womanist Theology in Beyoncé's Lemonade

Surviving Hardship Through Religion: Womanist Theology in Beyoncé’s Lemonade Surviving Hardship Through Religion: Womanist Theology in Beyoncé’s Lemonade Hanan Beyene Abstract In 2016, Beyoncé’s Lemonade premiered during a time of high political, social, and radical tension. Knowles creates an album that is not just about her, but also exhibits pride in blackness while revealing her vulnerability. Beyoncé exposed issues surrounding not only her relationship to her husband but also the African American community. Viewing Lemonade through the lens of Delores S. Williams’s definition of Womanist testimony regarding the struggles of identity and survival, it is possible to trace this message retroactively through biblical times. Religious tools like The Curse of Ham caused a generational trauma within the African American commu- nity that created a brokenness that continues to resonate. Beyoncé exhibits religious allegories and themes through Womanist Theology by confronting the brokenness of her relationship in Lemonade. This includes the process of forgiving her husband’s infidelity and preserving her family unit. * Winner of the Deans’ Distinguished Essay Award Middle Tennessee State University 7 Scientia et Humanitas: A Journal of Student Research Introduction Racial division became an increasingly incendiary debate during 2016. A major focus in the cultural landscape was police brutality; in the previous year, black men faced the highest rate of U.S. police killings,1 which brought attention to the history of racism and discrimination within governmental institutions. The ongoing presidential race illustrated that “the political divide is much more about culture, identity, and race.”2 Numerous people decried the rhetoric of Donald Trump, the Republican candidate, who they claimed spouted hate and bigotry. -

Beyoncé's True Political Statement This Week? It

11/5/2016 Beyoncé’s True Political Statement This Week? It Wasn’t at a Clinton Rally - The New York Times http://nyti.ms/2ebBcFh MUSIC Beyoncé’s True Political Statement This Week? It Wasn’t at a Clinton Rally By WESLEY MORRIS NOV. 5, 2016 I feel bad for anyone who still hasn’t learned to speak Beyoncé. Her language is the body. It’s stagecraft. It’s Instagram posts. She doesn’t speak; she signifies. And her performance on Friday at a Hillary Clinton rally in Cleveland won excitement and dismay over the possibility that she had reached some partisan peak by announcing that she was officially “with her.” But anyone who caught her appearance on Wednesday at the 50th annual Country Music Association Awards in Nashville knew that while Friday might have been, for Mrs. Clinton, strategically necessary, it was also politically anticlimactic. Beyoncé had already been with her — three of them, in fact. Partway through the broadcast, she arrived flanked by the Dixie Chicks, a trio of once insanely popular, then absurdly disgraced musicians who keep on going anyway. Together, they did a version of Beyoncé’s twangy scorcher “Daddy Lessons,” with a little of the Dixie Chicks’ “Long Time Gone” woven in toward the end. As polemical television, it was powerfully sly. The Cleveland show — which also featured Beyoncé’s husband, Jay Z, and Chance the Rapper — reeked of a kind of political desperation. (The Clinton campaign hopes to get more young people and black people to the polls on Election Day.) But Beyoncé diverged from desperate.