Womanist Theology in Beyoncé's Lemonade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Relatório Final

Relatório de Bolsa de Iniciação Científica Relatório Final Número do Processo: 2018/11470-1 Nome do Projeto: Inovação Audiovisual e a Voz Política em Let England Shake, Biophilia e Lemonade Vigência: 01/10/2018 a 30/09/2019 Período coberto pelo relatório: 10/03/2019 - 30/09/2019 Nome do Beneficiário/Bolsista: Fernando Paes de Oliveira Chaves Guimarães Nome do Responsável/Orientador: Cecília Antakly de Mello Fernando Paes de Oliveira Chaves Guimarães Cecília Antakly de Mello b) Resumo do plano inicial e das etapas já descritas em relatórios anteriores O projeto Inovação audiovisual e a voz política em Let England Shake, Biophilia e Lemonade teve como proposição inicial a investigação de novas formas audiovisuais que, de certo modo, são derivadas dos videoclipes e compõem um amálgama entre música e audiovisual. Em um primeiro momento, foi realizada uma extensa pesquisa sobre a história do videoclipe, suas origens e influências formais. Para essa pesquisa, utilizei uma bibliografia extensa, composta por autores como Arlindo Machado, Ken Dancyger, Kristin Thompson e David Bordwell, Flora Correia e Carol Vernallis. A obra Experiencing Music Video, de Carol Vernallis foi muito importante para o desenvolvimento da pesquisa e o uso da reserva técnica da bolsa para a aquisição dessa obra foi fundamental, uma vez que não a encontrei em bibliotecas públicas. Após o levantamento bibliográfico incial, foi realizada uma pesquisa sobre a biografia das artistas, de modo a possibilitar um melhor entendimento do contexto em que cada uma das obras foi lançada e a trajetória das três artistas até o momento de criação dos álbuns. Em seguida, realizei uma análise meticulosa de Let England Shake e Lemonade. -

Narrative Strategies and Music in Visual Albums

Narrative strategies and music in visual albums Lolita Melzer (6032052) Thesis BA Muziekwetenschap MU3V14004 2018-2019, block 4 University of Utrecht Supervisor: dr. Olga Panteleeva Abstract According to E. Ann Kaplan, Andrew Goodwin and Carol Vernallis, music videos usually do not have a narrative, at least not one like in classical Hollywood films. David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson state that such a narrative consists of events that are related by cause and effect and take place in a particular time and place. However, articles about music videos have not adequately addressed a new trend, namely the so called “visual album”. This medium is a combination of film and music video elements. Examples are Beyoncé’s much discussed visual album Lemonade from 2016 and Janelle Monáe’s “emotion picture” Dirty Computer from 2018. These visual albums are called ‘narrative films’ by sites such as The Guardian, Billboard and Vimeo, which raises questions about how narrative works in these media forms, because they include music videos which are usually non-narrative. It also poses the question how music functions with the narrative, as in most Hollywood films the music shifts to the background. By looking at the classical Hollywood narrative strategy and a more common strategy used in music videos, called a thread or motif strategy by Vernallis, I have analysed the two visual albums. After comparing them, it seems that both Lemonade and Dirty Computer make use of the motif strategy, but fail in achieving a fully wrought film narrative. Therefore, a different description to visual albums than ‘narrative film’, could be considered. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

Beyoncé's Lemonade Collaborator Melo-X Gives First Interview on Making of the Album.” Pitchfork, 25 Apr

FACULTADE DE FILOLOXÍA DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOLOXÍA INGLESA GRAO EN INGLÉS: ESTUDOS LINGÜÍSTICOS E LITERARIOS Beyoncé’s Lemonade: “A winner don’t quit” ANDREA PATIÑO DE ARTAZA TFG 2017 Vº Bº COORDINADORA MARÍA FRÍAS RUDOLPHI Table of Contents Abstract 1. Introduction 3 2. Methodology 4 3. Beyonce's Lemonade (2016) 5 3.1 Denial: “Hold Up” 6 3.2 Accountability: “Daddy Lessons” 12 3.3 Hope: “Freedom” 21 3.4 Formation 33 4. Conclusion 44 5. Works Cited 46 Appendix 49 Abstract Beyoncé’s latest album has become an instant social phenomenon worldwide. Given its innovative poetic, visual, musical and socio-politic impact, the famous and controversial African American singer has taken an untraveled road—both personal and professional. The purpose of this essay is to provide a close reading of the poetry, music, lyrics and visuals in four sections from Beyoncé’s critically acclaimed Lemonade (2016). To this end, I have chosen what I believe are the most representative sections of Lemonade together with their respective songs. Thus, I focus on the song “Hold Up” from Denial; “Daddy Lessons” from Accountability, “Freedom” from Hope, and “Formation,” where Beyoncé addresses topics such as infidelity, racism, women’s representation, and racism and inequality. I analyse these topics through a close-reading and interpretation of Warsan Shire’s poetry (a source of inspiration), as well as Beyoncé’s own music, lyrics, and imagery. From this analysis, it is safe to say that Lemonade is a relevant work of art that will perdure in time, since it highlights positive representations of African-Americans, at the same time Beyoncé critically denounces the current racial unrest lived in the USA. -

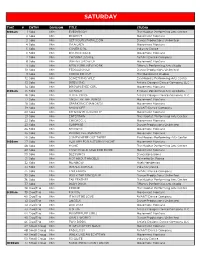

VIRTUAL LINEUP.Xlsx

SATURDAY TIME # ENTRY DIVISION TITLE STUDIO 8:00am 1 Solo Mini EVERYBODY The Habitat Performing Arts Center 2 Solo Mini RESPECT Movement Montana 3 Solo Mini GET YOUR SPARKLE ON Dance Productions Unlimited 4 Solo Mini I'M A LADY Movement Montana 5 Solo Mini COVER GIRL Industry Dance 6 Solo Mini BOUNCE BACK Movement Montana 7 Solo Mini I WANNA DANCE AVANTI Dance Company 8 Solo Mini WHEN I GROW UP Movement Montana 9 Solo Mini NEW YORK, NEW YORK Tiffany's Performing Arts Studio 10 Solo Mini FERGALICIOUS Dance Productions Unlimited 11 Solo Mini CHECK ME OUT The Movement Studios 12 Solo Mini SOMETHING WILD Eva Moore's Performing Arts Center 13 Solo Mini BIRDSONG Artistic Designs Dance Company LLC 14 Solo Mini BROWN EYED GIRL Movement Montana 8:30am 15 Solo Mini GO SOLO 8 Count Performing Arts Academy 16 Solo Mini LITTLE VOICE Artistic Designs Dance Company LLC 17 Solo Mini ANGEL BY THE WINGS Movement Montana 18 Solo Mini SPARKLING DIAMONDS Movement Montana 19 Solo Mini SHOW OFF AVANTI Dance Company 20 Solo Mini MY NEW PHILOSOPHY Movement Montana 21 Solo Mini ENTERTAIN The Habitat Performing Arts Center 22 Solo Mini CHICAGO, IL Movement Montana 23 Solo Mini SURPRISE Dance Productions Unlimited 24 Solo Mini SHOWOFF Movement Montana 25 Solo Mini PAVING THE RUNWAY Movement Montana 26 Solo Mini SOMEWHERE OUT THERE Eva Moore's Performing Arts Center 9:00am 27 Solo Mini LULLABY FOR A STORMY NIGHT Movement Montana 28 Solo Mini HOME The Habitat Performing Arts Center 29 Solo Mini HOW COULD I ASK FOR MORE Movement Montana 30 Solo Mini BLESSINGS DanceXpressions -

Beyoncé, Bella Y Talentosa

Image not found or type unknown www.juventudrebelde.cu Image not found or type unknown Beyoncé Autor: Internet Publicado: 21/09/2017 | 06:38 pm Beyoncé, bella y talentosa El pasado 4 de septiembre, Beyoncé Giselle Knowles-Carter, para todos Beyoncé, arribó a su 35 cumpleaños esta reconocida cantante que saltó a la fama a finales de los 90 Publicado: Lunes 12 septiembre 2016 | 11:02:28 pm. Publicado por: Juventud Rebelde El pasado 4 de septiembre, Beyoncé Giselle Knowles-Carter —para todos Beyoncé— arribó a su 35 cumpleaños. Nacida en Houston, Texas, en 1981, esta reconocida cantante, bailarina, modelo, actriz y empresaria estadounidense se presentó en diversos concursos de canto y baile cuando era niña y saltó a la fama a finales de los 90 como vocalista principal del grupo femenino de R&B, Destiny´s Child, que manejado por su padre, Mathew Knowles, se convirtió en uno de los de su tipo que ha conseguido mayores ventas de la historia. Dangerously In Love (2002) se nombra, por su parte, el álbum debut de Beyoncé, el cual la consagró como artista solista en todo el mundo. Con el vendió 11 millones de copias, ganó cinco premios Grammy, al tiempo que colocó dos de sus sencillos en el número uno del Billboard Hot 100: Crazy in Love y Baby Boy. No obstante, la disolución de Destiny´s Child no ocurrió hasta 2005. Fue entonces cuando la afamada intérprete presentó su segundo disco de estudio, B´Day, que contenía los éxitos Déja Vu, Irreplaceable y Beautiful liar. B´Day salió en 2006, año en que Beyoncé incursionó en el cine, en la película Dreamgirls, con un papel nominado al Globo de Oro. -

Beyoncé's True Political Statement This Week? It

11/5/2016 Beyoncé’s True Political Statement This Week? It Wasn’t at a Clinton Rally - The New York Times http://nyti.ms/2ebBcFh MUSIC Beyoncé’s True Political Statement This Week? It Wasn’t at a Clinton Rally By WESLEY MORRIS NOV. 5, 2016 I feel bad for anyone who still hasn’t learned to speak Beyoncé. Her language is the body. It’s stagecraft. It’s Instagram posts. She doesn’t speak; she signifies. And her performance on Friday at a Hillary Clinton rally in Cleveland won excitement and dismay over the possibility that she had reached some partisan peak by announcing that she was officially “with her.” But anyone who caught her appearance on Wednesday at the 50th annual Country Music Association Awards in Nashville knew that while Friday might have been, for Mrs. Clinton, strategically necessary, it was also politically anticlimactic. Beyoncé had already been with her — three of them, in fact. Partway through the broadcast, she arrived flanked by the Dixie Chicks, a trio of once insanely popular, then absurdly disgraced musicians who keep on going anyway. Together, they did a version of Beyoncé’s twangy scorcher “Daddy Lessons,” with a little of the Dixie Chicks’ “Long Time Gone” woven in toward the end. As polemical television, it was powerfully sly. The Cleveland show — which also featured Beyoncé’s husband, Jay Z, and Chance the Rapper — reeked of a kind of political desperation. (The Clinton campaign hopes to get more young people and black people to the polls on Election Day.) But Beyoncé diverged from desperate. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

From Bandannas to Berets: a Critical Analysis of Beyoncé's “Formation” Music Video by Kesha Shalyn James a Thesis Submit

From Bandannas to Berets: A Critical Analysis of Beyoncé’s “Formation” Music Video by Kesha Shalyn James A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Communication Auburn, Alabama August 5, 2017 Keywords: Beyoncé, Formation, Black women, Black music, Black culture, media representations Copyright 2017 by Kesha Shalyn James Approved by Susan L. Brinson, Chair, Professor of Communication & Journalism George Plasketes, Professor of Communication & Journalism Kevin Smith, Associate Professor of Communication & Journalism Abstract The release of Beyoncé’s “Formation” music video as well as her debut performance of the song at the 2016 Super Bowl has incited debate and controversy across the United States. While some feel empowered and prideful, others are angered and outraged by the lyrical and visual messages Beyoncé communicates in this mediated text. Applying a critical/cultural studies perspective lens, this study explains how Beyoncé challenges the sexist and racist dominant ideology in the United States. Critically analyzing the visual and lyrical composition of “Formation,” this analysis interrogates the messages of both race and gender as well as the representation of Black Women. The findings indicate a direct challenge to white androcentric power as the visuals and lyrics re-appropriate stereotypical images of Black Women, thus demonstrating Black Women’s power and dominance in society. The implications of explaining the ways in which Beyoncé communicates what and how it means to be a Black Woman in “Formation” inform and explain the social, political, and economic reality of Black Women in the United States today, as mediated texts re-present everyday reality. -

Université Du Québec À Montréal

UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL LES STARS ET LE CAPITAL DE L’INTIME : ÉNONCIATION FÉMINISTE POP CONTEMPORAINE THÈSE PRÉSENTÉE COMME EXIGENCE PARTIELLE DU DOCTORAT EN ÉTUDES LITTÉRAIRES PAR SANDRINE GALAND SEPTEMBRE 2020 UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL Service des bibliothèques Avertissement La diffusion de cette thèse se fait dans le respect des droits de son auteur, qui a signé le formulaire Autorisation de reproduire et de diffuser un travail de recherche de cycles supérieurs (SDU-522 – Rév.10-2015). Cette autorisation stipule que «conformément à l’article 11 du Règlement no 8 des études de cycles supérieurs, [l’auteur] concède à l’Université du Québec à Montréal une licence non exclusive d’utilisation et de publication de la totalité ou d’une partie importante de [son] travail de recherche pour des fins pédagogiques et non commerciales. Plus précisément, [l’auteur] autorise l’Université du Québec à Montréal à reproduire, diffuser, prêter, distribuer ou vendre des copies de [son] travail de recherche à des fins non commerciales sur quelque support que ce soit, y compris l’Internet. Cette licence et cette autorisation n’entraînent pas une renonciation de [la] part [de l’auteur] à [ses] droits moraux ni à [ses] droits de propriété intellectuelle. Sauf entente contraire, [l’auteur] conserve la liberté de diffuser et de commercialiser ou non ce travail dont [il] possède un exemplaire.» REMERCIEMENTS Je voudrais tout d’abord remercier Martine Delvaux, ma directrice, dont la rencontre comme écrivaine, féministe, chercheuse et professeure a été déterminante. Merci pour ta rigueur et ta droiture, auxquelles est venue se joindre une disponibilité aussi généreuse qu’immuable. -

Volume 16, Number 2 Fall 2017 Taboo: the Journal of Culture and Education Volume 16, Number 2, Fall 2017 Editors in Chief: Kenneth J

Fall 2017 Fall Volume 16, Number 2 Fall 2017 Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education Volume 16, Number 2, Fall 2017 Editors in Chief: Kenneth J. Fasching-Varner, Louisiana State University David Lee Carlson, Arizona State University Senior Editors: Renee DesMarchelier, University of Southern Queensland Donna Y. Ford, Vanderbilt University Founding & Consulting Editor: Shirley R. Steinberg, University of Calgary Editorial Assistants: Anna Montana Cirell, Arizona State University Joshua Cruz, Arizona State University Lindsay Stewart, Louisiana State University Chau B. Vu, Louisiana State University Timothy Wells, Arizona State University Shufang Yang, Louisiana State University Honorary Editorial Board: Russell Bishop, University of Waikato, Aotearoa, New Zealand Ramón Flecha, Universitat de Barcelona Henry A. Giroux, McMaster University Ivor Goodson, University of Brighton, United Kingdom Aaron Gresson, Pennsylvania State University Rhonda Hammer, University of California, Los Angeles Douglas Kellner, University of California, Los Angeles Ann Milne, Kia Aroha College, Auckland, New Zealand Christine Quail, McMaster University William Reynolds, Georgia Southern University Birgit Richard, Goethe University, Frankfurt John Smyth, Federation University of Australia Leila Villaverde, University of North Carolina at Greensboro Board Members, In Memorium: Eelco Buitenhuis, University of the West of Scotland Brenda Jenkins, City University of New York Graduate Center Joe L. Kincheloe, McGill University (Founding Editor) Pepi Leistyna, University