Shades of Water in the Landscape: Exploring the Schematics of Ancient Water Management System in Dandabhukti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Battle and Self-Sacrifice in a Bengali Warrior's Epic

Western Washington University Western CEDAR Liberal Studies Humanities 2008 Battle nda Self-Sacrifice in a Bengali Warrior’s Epic: Lausen’s Quest to be a Raja in Dharma Maṅgal, Chapter Six of Rites of Spring by Ralph Nicholas David Curley Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/liberalstudies_facpubs Part of the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Curley, David, "Battle nda Self-Sacrifice in a Bengali Warrior’s Epic: Lausen’s Quest to be a Raja in Dharma Maṅgal, Chapter Six of Rites of Spring by Ralph Nicholas" (2008). Liberal Studies. 7. https://cedar.wwu.edu/liberalstudies_facpubs/7 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Humanities at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Liberal Studies by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 6. Battle and Self-Sacrifice in a Bengali Warrior’s Epic: Lausen’s Quest to be a Raja in Dharma Ma2gal* INTRODUCTION Plots and Themes harma Ma2gal are long, narrative Bengali poems that explain and justify the worship of Lord Dharma as the D eternal, formless, and supreme god. Surviving texts were written between the mid-seventeenth and the mid-eighteenth centuries. By examining the plots of Dharma Ma2gal, I hope to describe features of a precolonial Bengali warriors” culture. I argue that Dharma Ma2gal texts describe the career of a hero and raja, and that their narratives seem to be designed both to inculcate a version of warrior culture in Bengal, and to contain it by requiring self-sacrifice in both battle and “truth ordeals.” Dharma Ma2gal *I thank Ralph W. -

History, Sculpture and Culture of Raghunath Jew Temple of Raghunath Bari, East Midnapore, India - a Photographic Essay

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 144 (2020) 397-413 EISSN 2392-2192 History, Sculpture and Culture of Raghunath Jew Temple of Raghunath Bari, East Midnapore, India - A Photographic Essay Prakash Samanta1, Pijus Kanti Samanta2,* 1Department of Environmental Science, Directorate of Distance Education, Vidyasagar University, Midnapore, West Bengal, India 2Department of Physics (PG & UG), Prabhat Kumar College, Contai - 721404, Purba Medinipur, West Bengal, India *E-mail address: [email protected] ABSTRACT Among the old temples which are under the Kashijora Pargana, Raghunath Jew temple (also known as Thakurbari) is very remarkable for its sculpture and culture of seventeenth century. This is a very old temple in the worship of Goddess Rama-Sita. The temple is a unique with its ancient constructions, and sculpture in its walls, and columns. A festival in the worship of lord Rama is held every year on Dashera and runs over a month. People of all community, caste and culture assemble in this festival. This festival also helps to develop the economy of not only the temple authority but also the people of the surrounding villages. The Ratha (Chariot), which runs in the day of Dashera, is very unique in the entire Midnapore district. It is made up of wood and contains several sculptural designs. Although there is as such no detailed historical record of this temple but still it is silently preserving the culture of the ancient Bengal over last three centuries. Keywords: Kashijora Pargana, Temple, Chariot, Archaeology, Bengal ( Received 24 March 2020; Accepted 15 April 2020; Date of Publication 16 April 2020 ) World Scientific News 144 (2020) 397-413 1. -

YSPM News Letter Volumn – 1 Yogoda Satsanga Palpara Mahavidyalaya (NAAC Accredited – B) at + P.O

YSPM News Letter Volumn – 1 Yogoda Satsanga Palpara Mahavidyalaya (NAAC Accredited – B) At + P.O. – Palpara, Dist. – Purba Medinipur - 721458, West Bengal “True wisdom : Understanding how the one consciousness becomes all things.” -Sri Sri Paramahansa Yogananda Message Editorial I am delighted to know that our College Reflection of the achievements, programmes and activities is bringing out a News Letter covering different undertaken by the College through its documentation is a quality bench programmes and activities organised by its mark for higher education. Documentation of the programmes and activities different Teaching Departments. It is a sincere in the shape of a News Letter at regular interval inspires an Institution in doing the quality assurance activities both in academic and non –academic and qualitative attempt to document all activities and programmes areas of development. The initiative taken by our Principal to publish News done in scholastic and co-scholastic perspective. It will be a Letter regularly is no doubt essential in creating work culture, research befitting initiative for students, both continuing and passouts, culture and quality culture in the Institution. This News Letter going to be members of teaching and non-teaching staff, parents and the public released, gives a synoptic profile picture of activities and programmes of the region to know the achievements and developments going on undertaken by different Departments of our College during the period 2016- in this Institution. Besides, it would definitely be an inspiration for 17 academic session to the mid of the academic session, 2018-19 which will students and staff to work for the Institution to take it to greater inspire the members of teaching and non-teaching staff of our College to heights. -

Freshwater Fish Survey

Final Report on Freshwater Fish Survey Period 2 years (22/04/2013 - 21/04/2015) Area of Study PURBA MEDINIPUR DISTRICT West Bengal Biodiversity Board GENERAL INFORMATION: Title of the project DOCUMENTATION OF DIVERSITY OF FRESHWATER FISHES OF WEST BENGAL Area of Study to be covered PURBA MEDINIPUR DISTRICT Sanctioning Authority: The West Bengal Biodiversity Board, Government of West Bengal Sanctioning Letter No. Memo No. 239/3K(Bio)-2/2013 Dated 22-04-2013 Duration of the Project: 2 years : 22/04/2013 - 21/04/2015 Principal Investigator : Dr. Tapan Kr. Dutta, Asstt. Professor in Life Sc. and H.O.D., B.Ed. Department, Panskura Banamali College, Purba Medinipur Joint Investigator: Dr. Priti Ranjan Pahari, Asstt. Professor in Zoology , Tamralipta Mahavidyalaya, Purba Medinipur Acknowledgement We express our indebtedness to The West Bengal Biodiversity Board, Government of West Bengal for financial assistance to carry out this project. We express our gratitude to Dr. Soumendra Nath Ghosh, Senior Research Officer, West Bengal Biodiversity Board, Government of West Bengal for his continuous support and help towards this project. Prof. (Dr.) Nandan Bhattacharya, Principal, Panskura Banamali College and Dr. Anil Kr. Chakraborty, Teacher-in-charge, Tamralipta Mahavidyalaya, Tamluk, Purba Medinipur for providing laboratory facilities. We are also thankful to Dr. Silanjan Bhattacharyya, Profesasor, West Bengal State University, Barasat and Member of West Bengal Biodiversity Board for preparation of questionnaire for fish fauna survey and help render for this work. Gratitude is extended to Dr. Nirmalys Das, Associate Professor, Department of Geography, Panskura Banamali College, Purba Medinipur for his cooperation regarding position mapping through GPS system and help to finding of location waterbodies of two district through special GeoSat Software. -

Journal of History

Vol-I. ' ",', " .1996-97 • /1 'I;:'" " : ",. I ; \ '> VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY Journal of History S.C.Mukllopadhyay Editor-in-Chief ~artment of History Vidyasagar University Midnapore-721102 West Bengal : India --------------~ ------------ ---.........------ I I j:;;..blished in June,1997 ©Vidyasagar University Copyright in articles rests with respective authors Edi10rial Board ::::.C.Mukhopadhyay Editor-in-Chief K.K.Chaudhuri Managing Editor G.C.Roy Member Sham ita Sarkar Member Arabinda Samanta Member Advisory Board • Prof.Sumit Sarkar (Delhi University) 1 Prof. Zahiruddin Malik (Aligarh Muslim University) .. <'Jut". Premanshu Bandyopadhyay (Calcutta University) . hof. Basudeb Chatterjee (Netaji institute for Asian Studies) "hof. Bhaskar Chatterjee (Burdwan University) Prof. B.K. Roy (L.N. Mithila University, Darbhanga) r Prof. K.S. Behera (Utkal University) } Prof. AF. Salauddin Ahmed (Dacca University) Prof. Mahammad Shafi (Rajshahi University) Price Rs. 25. 00 Published by Dr. K.K. Das, Registrar, Vidyasagar University, Midnapore· 721102, W. Bengal, India, and Printed by N. B. Laser Writer, p. 51 Saratpalli, Midnapore. (ii) ..., -~- ._----~~------ ---------------------------- \ \ i ~ditorial (v) Our contributors (vi) 1-KK.Chaudhuri, 'Itlhasa' in Early India :Towards an Understanding in Concepts 1 2.Bhaskar Chatterjee, Early Maritime History of the Kalingas 10 3.Animesh Kanti Pal, In Search of Ancient Tamralipta 16 4.Mahammad Shafi, Lost Fortune of Dacca in the 18th. Century 21 5.Sudipta Mukherjee (Chakraborty), Insurrection of Barabhum -

Other Places

H A L D I A Haldia Dock Complex was commissioned as a Bulk Handling Dock System of KoPT in 1977 on the confluence of two rivers Hooghly and Haldi. It is an impounded dock system operated by a single Lock Entrance of 330 metres length and 39 metres in width. In the year 2003-2004, Haldia Dock Complex has handled 32.5 million metric ton of sea-borne Cargo out of which 14.05 moved by Rail. In the year 2004-05 (April to October) Haldia Dock Complex has handled 20.4 million metric ton out of which the rail share is 8.23 million metric ton. Haldia Port now holds 4th position as far as volume of traffic handled is concerned, amongst major Ports of India. Connectivity : Direct EMU service from Howrah (H 601) and Suburban EMU service and Mail Express (7045, 8030) upto Mecheda and then by road to Haldia via Tamluk. T A M L U K Ancient Tamralipta & Goddess Bargabhima Temple : The principal object of interest in the Tamluk town is the temple of Bargabhima, which represents ‘Tara’, one form of Sakti …… situated on the banks of the Rupnarayan river. Some say that it was built by Biswakarma, the engineer of the gods. The temple is on a raised platform accessible by a flight of stairs consisting of 22 steps. The skill and ingenuity displayed in the construction of the temple still attracts admiration. The idol is formed from a single block of stone with the hands and feet attached to it. The goddess is represented standing on the body of Siva, and has four hands. -

Applying a Coupled Nature–Human Flood Risk Assessment Framework in a Case for Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

water Article Climate Justice Planning in Global South: Applying a Coupled Nature–Human Flood Risk Assessment Framework in a Case for Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam Chen-Fa Wu 1 , Szu-Hung Chen 2, Ching-Wen Cheng 3 and Luu Van Thong Trac 1,* 1 Department of Horticulture, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung City 402, Taiwan; [email protected] 2 International Master Program of Agriculture, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung City 402, Taiwan; [email protected] 3 The Design School, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +886-4-2285-9125 Abstract: Developing countries in the global south that contribute less to climate change have suffered greater from its impacts, such as extreme climatic events and disasters compared to developed countries, causing climate justice concerns globally. Ho Chi Minh City has experienced increased intensity and frequency of climate change-induced urban floods, causing socio-economic damage that disturbs their livelihoods while urban populations continue to grow. This study aims to establish a citywide flood risk map to inform risk management in the city and address climate justice locally. This study applied a flood risk assessment framework integrating a coupled nature–human approach and examined the spatial distribution of urban flood hazard and urban flood vulnerability. A flood hazard map was generated using selected morphological and hydro-meteorological indicators. A flood Citation: Wu, C.-F.; Chen, S.-H.; vulnerability map was generated based on a literature review and a social survey weighed by experts’ Cheng, C.-W.; Trac, L.V.T. -

Prout in a Nutshell Volume 3 Second Edition E-Book

SHRII PRABHAT RANJAN SARKAR PROUT IN A NUTSHELL VOLUME THREE SHRII PRABHAT RANJAN SARKAR The pratiika (Ananda Marga emblem) represents in a visual way the essence of Ananda Marga ideology. The six-pointed star is composed of two equilateral triangles. The triangle pointing upward represents action, or the outward flow of energy through selfless service to humanity. The triangle pointing downward represents knowledge, the inward search for spiritual realization through meditation. The sun in the centre represents advancement, all-round progress. The goal of the aspirant’s march through life is represented by the swastika, a several-thousand-year-old symbol of spiritual victory. PROUT IN A NUTSHELL VOLUME THREE Second Edition SHRII PRABHAT RANJAN SARKAR Prout in a Nutshell was originally published simultaneously in twenty-one parts and seven volumes, with each volume containing three parts, © 1987, 1988, 1989, 1990 and 1991 by Ánanda Márga Pracáraka Saîgha (Central). The same material, reorganized and revised, with the omission of some chapters and the addition of some new discourses, is now being published in four volumes as the second edition. This book is Prout in a Nutshell Volume Three, Second Edition, © 2020 by Ánanda Márga Pracáraka Saîgha (Central). Registered office: Ananda Nagar, P.O. Baglata, District Purulia, West Bengal, India All rights reserved by the publisher. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording -

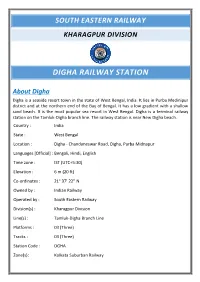

Digha Railway Station

SOUTH EASTERN RAILWAY KHARAGPUR DIVISION DIGHA RAILWAY STATION About Digha Digha is a seaside resort town in the state of West Bengal, India. It lies in Purba Medinipur district and at the northern end of the Bay of Bengal. It has a low gradient with a shallow sand beach. It is the most popular sea resort in West Bengal. Digha is a terminal railway station on the Tamluk-Digha branch line. The railway station is near New Digha beach. Country : India State : West Bengal Location : Digha - Chandaneswar Road, Digha, Purba Midnapur Languages [Official] : Bengali, Hindi, English Time zone : IST (UTC+5:30) Elevation : 6 m (20 ft) Co-ordinates : 21° 37' 22'' N Owned by : Indian Railway Operated by : South Eastern Railway Division(s) : Kharagpur Division Line(s) : Tamluk-Digha Branch Line Platforms : 03 (Three) Tracks : 03 (Three) Station Code : DGHA Zone(s): Kolkata Suburban Railway History Originally, there was a place called Beerkul, where Digha lies today. This name was referred in Warren Hastings's letters (1780) as Brighton of the East. An English businessman John Frank Snaith started living here in 1923 and his writings provided a good exposure to this place. He convinced West Bengal Chief Minister Bidhan Chandra Roy to develop this place to be a beach resort. An old Church is well famous in Digha, which can be seen near the Old Digha Main gate this place is also known as Alankarpur Digha. A new mission has been developed in New Digha which is known as Sindhur Tara which is beside Amrabati Park its a Church where you can wish for the welfare of your family and loved ones. -

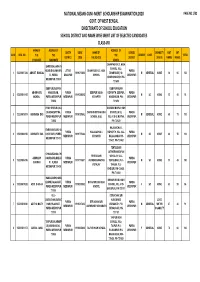

Purba Mednipur Merit List

NATIONAL MEANS‐CUM ‐MERIT SCHOLARSHIP EXAMINATION,2020 PAGE NO.1/82 GOVT. OF WEST BENGAL DIRECTORATE OF SCHOOL EDUCATION SCHOOL DISTRICT AND NAME WISE MERIT LIST OF SELECTED CANDIDATES CLASS‐VIII NAME OF ADDRESS OF ADDRESS OF QUOTA UDISE NAME OF SCHOOL DISABILITY MAT SAT SLNO ROLL NO. THE THE THE GENDER CASTE TOTAL DISTRICT CODE THE SCHOOL DISTRICT STATUS MARKS MARKS CANDIDATE CANDIDATE SCHOOL DHANYASRI K.C. HIGH SARBERIA,NARAYA SCHOOL, VILL- NDARI,BHAGWANPU UTTAR DHANYASRI K.C. HIGH PURBA 1 123205017226 ABHIJIT MANDAL 19190710003 DHANYASRI,P.O- M GENERAL NONE 58 65 123 R , PURBA DINAJPUR SCHOOL MEDINIPUR SRIKRISHNAPUR, PIN- MEDINIPUR 721655 721659 DEBIPUR,DEBIPUR, DEBIPUR MILAN ABHIMANYU NANDIGRAM , PURBA DEBIPUR MILAN VIDYAPITH, DEBIPUR, PURBA 2 123205011155 19191206002 M SC NONE 53 40 93 MONDAL PURBA MEDINIPUR MEDINIPUR VIDYAPITH NANDIGRAM, PIN- MEDINIPUR 721650 721650 PANCHPUKURIA,KA DAKSHIN MOYNA HIGH LIKADARI,MOYNA , PURBA DAKSHIN MOYNA HIGH SCHOOL (H.S.), PURBA 3 123205016015 ABHINABA DAS 19190105602 M GENERAL NONE 60 70 130 PURBA MEDINIPUR MEDINIPUR SCHOOL (H.S.) VILL+P.O-D. MOYNA, MEDINIPUR 721642 PIN-721629 KALAGACHIA J. RAMCHAK,RAMCHA PURBA KALAGACHIA J. VIDYAPITH, VILL VILL- PURBA 4 123205004150 ABHISHEK DAS K,KHEJURI , PURBA 19191707804 M SC NONE 63 55 118 MEDINIPUR VIDYAPITH KALAGACHIA PIN- MEDINIPUR MEDINIPUR 721431 721432, PIN-721432 TENTULBARI JATINDRANARAYAN CHINGURDANIA,CHI TENTULBARI VIDYALAY, VILL- ABHRADIP NGURDANIA,KHEJU PURBA PURBA 5 123205004156 19191703601 JATINDRANARAYAN TENTULBARI, P.O.- M SC NONE 51 49 100 BARMAN RI , PURBA MEDINIPUR MEDINIPUR VIDYALAY TIKASHI, P.S.- MEDINIPUR 721430 KHEJURI, PIN-721430, PIN-721430 NAMALBARH,NAMA BHOGPUR K.M. HIGH LBARH,KOLAGHAT , PURBA BHOGPUR K.M. -

Tamralipta Mahavidyalaya Vill

TAMRALIPTA MAHAVIDYALAYA VILL. - ABASBARI, P.O. - TAMLUK, DIST. - PURBA MEDINIPUR WEST BENGAL – 721 636 List of Equipments NIT NO-WBDHE /TM/eNIT-02/2019-20(2nd Call) Parameter Commercial/ Business Desktop Computer Quantity Bidder's to fillup the Compliance in (Approx.) Details ( only YES or NO is not Acceptable and will be Rejected Summarily ) Make HP/ Dell/ Lenovo only Model Vendor To Specify CPU Intel® 8th Generation Core™ i7 or Higher Chipset Intel B / Q Series Chipset or higher Bus Architecture 2 PCI Express (PCIe) or Higher Memory 4GB, UDIMM, DDR4-2666, extendable upto 32 GB Hard Disk 1TB (1000GB) 7200 rpm SATA 6Gbps or Higher Monitor TCO 7.0 certified 19.5 inch, 1600 x 900 LED Digital colour monitor Keyboard 104 Keys with USB interface Mouse Optical scroll Mouse with USB interface Graphics Intel UHD Graphics 630 Port Minimum (6) USB 3.1 Gen 1, (4) USB 2.0, (1) VGA, (1) DP, (1) HDMI, (1) RJ-45, Audio Cabinet Tower (15 Ltr or Higher) Networking 10/100/1000 On board integrated network port with remote booting facility, remote wake up, TPM enabled 1.2 chip using any Standard Management Software 53 OS Pre Loaded Windows 10 SL Original Licensed Version (Fifty Three) Environment ENERGY STAR 7.0 ; EPEAT Silver rating; GREENGUARD ; RoHS-compliant Power 180 watts, autosensing, 85% PSU or Higher Cables and Dust Good Quality Cables must be included Plug 1x VGA Cable for monitor to PC 1x HDMI Cable for monitor to PC 1x DP Cable for monitor to PC 2x Power Cable included. Dust Plug Complete Set (for USB, VGA, HDMI, DP and RJ45 Port ) Warranty 3 years Comprehensive onsite warranty on Desktop PC & Monitor Authorization Tender Specific Authorization Needed from OEM Brochure Need Brochure of the Respective Quoted Model UPS Make APC/BPE/Iball only Model Vendor To Specify INPUT Voltage (VAC) 100~300VAC Load Dependent Frequency (Hz) 50 / 60Hz ± 10Hz Auto Sensing OUTPUT Voltage AVR Mode 200-245V 53 Voltage Battery 230VAC 10% Mode (Fifty Three) Frequency (Hz) on 50/60Hz ± 0 1Hz Battery Waveform Simulated Sine Wave No. -

Dynamics of Land Use /Land Cover Changes and Its Impact on Land Surface Temperature in the Keleghai River Basin, West Bengal, India: a Remote Sensing Approaches

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 12, Issue 2, February-2021 579 ISSN 2229-5518 Dynamics of Land Use /Land Cover changes and Its Impact on Land Surface Temperature in The Keleghai River Basin, West Bengal, India: A Remote Sensing Approaches. Mr. Goutam Kumar Das M.Phil. Student of Department of Earth Science, Vidyasagar University, Medinipur, W.B, India Abstract: Land surface temperature is an important factor to play and change that estimate radiation budget and control the heat balance at the earth’s surface. Rapid population growth and changing the existing patterns of Land Use/Land Cover (LU/LC) globally, which is consequently increasing the land surface temperature (LST). The transformation of LU/LC due to rapid Built-up land expansion significantly affects the functions of Biodiversity and ecosystems as well as local and regional climates. This study evaluates the impact of LU/LC changes on LST for 2000, 2010 and 2020 in the keleghai River Basin using multi-temporal and multi-spectral Landsat-7 TM and Landsat-8 OLI satellite data sets. Our results indicated that, Built-up area and Brick kiln area were 1070.06 km2 and 46.18 km2 and decreased water bodies, agricultural land, agricultural fallow land and scrub land are 1382.13 km2, 4196.14 km2, 1529.95 km2 and 24.59 km2 respectively in the last 20 year in the study area. The distribution of changes in LST shows the Built-up area and Brick kiln area recorded the highest mean temperature and increased 26.72oC – 40.34oC and 29.28oC – 41.34oC respectively.