JEMMS 2/2014 Special Issue: Textbooks, Identity Politics And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Entries

List of Entries A Ahmad Raza Khan Barelvi 9th Month of Lunar Calendar Aḥmadābād ‘Abd al-Qadir Bada’uni Ahmedabad ‘Abd’l-RaḥīmKhān-i-Khānān Aibak (Aybeg), Quṭb al-Dīn Abd al-Rahim Aibek Abdul Aleem Akbar Abdul Qadir Badauni Akbar I Abdur Rahim Akbar the Great Abdurrahim Al Hidaya Abū al-Faḍl ‘Alā’ al-Dīn Ḥusayn (Ghūrid) Abū al-Faḍl ‘Allāmī ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn Khaljī Abū al-Faḍl al-Bayhaqī ʿAlāʾ al-DīnMuḥammad Shāh Khaljī Abū al-Faḍl ibn Mubarak ‘Alā’ ud-Dīn Ḥusain Abu al-Fath Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar ʿAlāʾ ud-Dīn Khiljī Abū al-KalāmAzād AlBeruni Abū al-Mughīth al-Ḥusayn ibn Manṣūr al-Ḥallāj Al-Beruni Abū Ḥafṣ ʿUmar al-Suhrawardī AlBiruni Abu’l Fazl Al-Biruni Abu’l Fazl ‘Allāmī Alfī Movements Abu’l Fazl ibn Mubarak al-Hojvīrī Abū’l Kalām Āzād Al-Huda International Abū’l-Fażl Bayhaqī Al-Huda International Institute of Islamic Educa- Abul Kalam tion for Women Abul Kalam Azad al-Hujwīrī Accusing Nafs (Nafs-e Lawwāma) ʿAlī Garshāsp Adaran Āl-i Sebüktegīn Afghan Claimants of Israelite Descent Āl-i Shansab Aga Khan Aliah Madrasah Aga Khan Development Network Aliah University Aga Khan Foundation Aligarh Muslim University Aga Khanis Aligarh Muslim University, AMU Agyaris Allama Ahl al-Malāmat Allama Inayatullah Khan Al-Mashriqi Aḥmad Khān Allama Mashraqi Ahmad Raza Khan Allama Mashraqui # Springer Science+Business Media B.V., part of Springer Nature 2018 827 Z. R. Kassam et al. (eds.), Islam, Judaism, and Zoroastrianism, Encyclopedia of Indian Religions, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1267-3 828 List of Entries Allama Mashriqi Bangladesh Jamaati-e-Islam Allama Shibili Nu’mani Baranī, Żiyāʾ al-Dīn Allāmah Naqqan Barelvīs Allamah Sir Muhammad Iqbal Barelwīs Almaniyya BāyazīdAnṣārī (Pīr-i Rōshan) Almsgiving Bāyezīd al-Qannawjī,Muḥammad Ṣiddīq Ḥasan Bayhaqī,Abūl-Fażl Altaf Hussain Hali Bāzīd Al-Tawḥīd Bedil Amīr ‘Alī Bene Israel Amīr Khusrau Benei Manasseh Amir Khusraw Bengal (Islam and Muslims) Anglo-Mohammedan Law Bhutto, Benazir ʿAqīqa Bhutto, Zulfikar Ali Arezu Bīdel Arkān al-I¯mān Bidil Arzu Bilgrāmī, Āzād Ārzū, Sirāj al-Dīn ‘Alī Ḳhān (d. -

Ideology of the Faraizi Movement of Bengal History 2001

IDEOLOGY OF THE FARAIZI MOVEMENT OF BENGAL ABSTRACT i THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF THE il "^ »L;i. ! HISTORY I i ^ if By » <t MUHAMMAD AHSAN ULLAH Under the Supervision of PROF. ISHTIYAQ AHMAD ZILLI CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2001 ABSTRACT The Faraizi movement of Bengal was the first organized Islamic revivalist movement in British India, it was not merely a religious movement but its activities also extended to socio-economic, political, cultural, dawah, and agrarian spheres. Its genesis could be traced to local factors such as religious^ socio-economic and political conditions prevailing at that time in Bengal. But it was also influenced by the general awakening in the Muslim world and the rise of Islamic revivalist movements during the 19**' century throughout the Muslim world. This movement was launched by Haji Shariatullah (17S1-1840) in the first quarter of nineteen century in British Bengal. The basic aims and objectives of the movement were related to the religious reform and restoration of the true Islamic spirit but gradually its activities were extended to the spheres of Politics, economy and culture as without all round upliftment of the Muslims no real change could be expected to take place. Morover, as Islam does not countenance a division among the various sphere^ of human society, the Faraizis could not have legitimately looked over these aspects. 2- This thesis seeks to put the the Faraizi movement in its correct perspective by working out its ideology in relation to not only religion but other aspects of its activities which covered politics, economy, culture etc. -

Chapter-3 Monitoring the Behaviour of Law Enforcement Agencies

Odhikar Report 2006 Published by Odhikar House No. 65 (2nd Floor), Block-E Road No. 17/A, Banani Dhaka-1213, Bangladesh Tel: 880 2 9888587, Fax: 880 2 9886208 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.odhikar.org Supported by Academy for Educational Development (AED) Eureka House No. 10 A Road No. 25 A, Banani Dhaka-1213, Bangladesh Tel: 880 2 9894016 Fax: 880 2 9894016 (Ext. 106) Website: www.aed-bd.org Cover Design Md. Sazzad Hussain Copyright c Odhikar Any material published in this report may be reproduced with acknowledgement to Odhikar Table of content Chapter 1 : AED and Odhikar: Four Years of Partnership 7 Chapter 2 : Civil and Political Rights in Bangladesh 11 Chapter 3 : Monitoring the Behaviour of 21 Law Enforcement Agencies Chapter 4 : Documentation and Fact Finding on 35 Human Rights Violations Chapter 5 : Human Rights Advocacy: The Media Roundtables 39 and a Regional Discussion Meeting Chapter 6 : Successful Outcomes of the Project 49 ANNEXTURE Annex-i Fact finding reports 2006 53 Annex-ii Keynote paper for Roundtable Meeting on 171 ‘Police Behaviour in Crowd Management’ Annex-iii Papers presented at the Regional Discussion Meeting 181 on Security and Law: South Asian perspective Annex-iv Newspaper clippings 215 Acknowledgement The Academy for Educational Development had supported Odhikar's work for four years - the last year being an extension to help the organisation complete its activities, carry out follow-up missions of noteworthy incidents of human rights violations and improve its fact finding skills. Odhikar would like to thank the AED for extending its project for another year, where time could also be spent in evaluating the work of the previous years. -

Global Digital Cultures: Perspectives from South Asia

Revised Pages Global Digital Cultures Revised Pages Revised Pages Global Digital Cultures Perspectives from South Asia ASWIN PUNATHAMBEKAR AND SRIRAM MOHAN, EDITORS UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS • ANN ARBOR Revised Pages Copyright © 2019 by Aswin Punathambekar and Sriram Mohan All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid- free paper First published June 2019 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication data has been applied for. ISBN: 978- 0- 472- 13140- 2 (Hardcover : alk paper) ISBN: 978- 0- 472- 12531- 9 (ebook) Revised Pages Acknowledgments The idea for this book emerged from conversations that took place among some of the authors at a conference on “Digital South Asia” at the Univer- sity of Michigan’s Center for South Asian Studies. At the conference, there was a collective recognition of the unfolding impact of digitalization on various aspects of social, cultural, and political life in South Asia. We had a keen sense of how much things had changed in the South Asian mediascape since the introduction of cable and satellite television in the late 1980s and early 1990s. We were also aware of the growing interest in media studies within South Asian studies, and hoped that the conference would resonate with scholars from various disciplines across the humanities and social sci- ences. -

NO PLACE for CRITICISM Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS NO PLACE FOR CRITICISM Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary WATCH No Place for Criticism Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary Copyright © 2018 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36017 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org MAY 2018 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36017 No Place for Criticism Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Information and Communication Act ......................................................................................... 3 Punishing Government Critics ...................................................................................................4 Protecting Religious -

Searching for the Greatest Bengali: the BBC and Shifting Identity

National Identities Vol. 10, No. 2, June 2008, 149Á165 Searching for the greatest Bengali: The BBC and shifting identity categories in South Asia Reece Jones* University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA Drawing on debates generated by the BBC Bengali Language Service’s naming of the greatest Bengali of all time, this article investigates the shifting boundaries between group identity categories in our ‘globalising’ world. First, the con- troversy over the meaning of the term ‘Bengali’, which emerged in contemporary Bangladesh and India in response to the BBC’s list, is investigated. Then writings and speeches of several of the individuals who were honoured as the greatest Bengalis are analysed in order to draw out the multiple ways they approached their own Bengali identities. In the conclusion, it is argued that rather than imagining the end of place-based identity categories through the process of globalisation, it is more useful to conceptualise shifting categories that continue Downloaded By: [Jones, Reece] At: 15:14 29 April 2008 to incorporate a place-based aspect, but in hybrid and contradictory ways. Keywords: categories; ethnicity; nations; globalisation; South Asia In Spring 2004, following the British Broadcasting Company’s naming of Winston Churchill as the greatest Briton of all time, the BBC Bengali Language Service conducted a survey of its twelve million listeners to determine the greatest Bengali of all time (BBC, 2004).1 Respondents were asked to rank their top five choices and in the end more than 100 individuals received votes. The top twenty were announced one per day beginning on 26 March, Bangladesh’s Independence Day, and ending on 15 April, the Bengali New Year’s Day, with the naming of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman as the greatest Bengali of all time. -

Islamic Education in Bangladesh: Second Year Report

ISLAMIC EDUCATION IN BANGLADESH: SECOND YEAR REPORT Mumtaz Ahmad Executive Summary 1. Islamic education in Bangladesh represents a wide variety of pedagogic approaches and institutional structures. First, there are private Quomi madrassas that are exclusively focused on traditional Islamic sciences. Then there are government-funded Alia madrassas that have added several modern subjects along with a condensed version of traditional Islamic education. Besides these two systems of madrassas, there is this phenomenon of the newly emerging English medium Islamic schools that offer an integrated curriculum combining both Islamic and modern, “secular” education. Finally, there are the public universities’ programs in Islamic Studies and Islamic History and Culture that have introduced, without discarding the body of learned tradition, considerable changes over the years by adding a variety of new disciplines as well as relatively recent scholarship, including Western, in their programs. 2. Islamic education in public universities could have emerged as an alternative to the higher education offered in traditional madrassas, but having been modeled initially on the Delhi College and the Calcutta Madrassa, it has neither been able to offer a modern orientation and critical stance in Islamic Studies, nor it has achieved the legitimacy of traditional Islamic scholarship. 3. As for the madrassa education, there is more continuity than change. No serious reform effort is currently underway either in the Alia or the Quomi system. In a political context defined by (a) intense hostility between the two mainstream political parties and (b) the imposition of emergency and the postponement of elections by the Care Taker Government, the issues such as the political parties’ reforms and the future of democracy in Bangladesh seem to have overshadowed whatever little enthusiasm was there for reforms in the Alia madrassas a couple of years ago in the government circles. -

Macroeconomic Variables and Poverty in Palestine: Polices, Effects, Implications and Poverty Reduction

Al-Azhar University-Gaza Deanship of Postgraduate Studies Faculty of Economics and Administrative Science Department of Economy Macroeconomic Variables and Poverty in Palestine: Polices, Effects, Implications and Poverty Reduction By Hakam Abdel Hakeem Atallah AL Ajrami Supervisor Dr. Mahmoud M. Sabra Associate Professor of Economics A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master in Economy 2017 بسم اهلل الرمحن الرحيم قُلْ إِنَّ صَﻻَتِي وَنُسُكِي وَمَحْيَايَ وَمَمَاتِي لِلّهِ رَبِّ الْعَالَمِنيَ }162{ ﻻَ شَرِيكَ لَهُ وَبِذَلِكَ أُمِرْتُ وَأَنَاْ أَوَّلُ املُسْلِمِنيَ }163{ صدق هللا العظيم اﻷنعام 162 163- Holy Quran quote i Dedication I dedicate my study to my dear parents My sisters and brothers My friends and colleagues My teachers at Al-Azhar University ii Acknowledgements First, I would like to express my appreciation to Allah for giving me the power, knowledge, and health to start and complete this thesis. Special thanks are due to Dr. Mahmoud Sabra, my thesis supervisor, for his endless support, guidance, and knowledge. I appreciate and thank the referees; Dr.Abdel Hakeem Ahmad Eltalla (Associate Professor of Economics, Alaqsa University) and Dr.Naseem Abo Jamie (Associate Professor of Economics, Al Azhar University). for their pieces of advice, comments, and great efforts. Also, I thank Dr.Abdullah Kurraz for his English language editing, and my friend Haytham Al Najar for his help in the econometric section. iii Abstract This study investigates the impact of macroeconomic variables on poverty in Palestine for the period 1995 to 2014 by using linear regression and simultaneous equations analysis. In addition, descriptive analysis has been used to identify the phenomenon of poverty, its causes, measurements and its indicators after reviewing the poverty theories that explain poverty. -

Desecularisation and Rise of Political Islam* in Bangladesh*

Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bangladesh (Hum.), Vol. 57(1), 2012, pp. 29-40 * DESECULARISATION AND RISE OF POLITICAL ISLAM * IN BANGLADESH Harun-or-Rashid* Introduction Forty years ago Bangladesh, a breakaway state in south Asia, came to be founded upon the ideal of secularism as one of the fundamental state principles by shunning the Pakistani path of use of religion in politics. The new republic under the leadership of its founding father, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was believed to be free from communal politics once and for all. However, to utter surprise of many, very soon use of religion in public matters and rise of Islamism being the religion of the dominant majority community with resultant impact of communalisation marked a pronounced manifestation. How to explain this? What are the factors that may account for this development? What is the future of syncretism upon which the Bangladesh society is historically based? The present paper is an attempt to examine the process of desecularisation and the rise of political Islam in Bangladesh keeping in view the above questions. The discourse can be better understood in terms of three distinct eras of political rule. First, the Mujib era (1972-1975) that was characterized by the prohibition of use of religion in politics. Second, the military era (1976-1990) under General Zia and Ershad, which saw the re- emergence of political Islam within the arena of mainstream politics. Third, the democratic era spanning over the rule of Begum Khaleda Zia and Sheikh Hasina (1991 to date ), a period marked by the emergence of a host of militant Islamist groups followed by attempts to curb influence of Islam as a political ideology. -

Car Loan Final List of Officer by LPR Seniority.Xlsx

RESTRICTED LIST OF OFFICERS LT CDR & ABOVE ( SENIORITY AS PER DATE OF RETIREMENT Wef-27 JULY 2020) Ser Rank & Name P No Billet / Appointment Age Limit 1 Lt Cdr M Golam Farooq, (SD)(R), BN 1563 BNS HAJI MOHSIN / EO 8/1/2020 2 Cdre Mohammad Rashed Ali, (TAS), NGP, ndc, psc, BN 535 BNS HAJI MOHSIN / CHINA FRIGATE (TYPE 053H3) / Proj Offr&Overall IC 25-08-2020 3 Cdre Syed Maksumul Hakim, (ND), BSP, ndc, ncc, psc, BN 464 BNS HAJI MOHSIN / Embassy of Bangladesh / Defense Advisor-Sri Lanka 27-08-2020 4 Cdre Mohammed Jahangir Alam, (E), NUP, ndc, psc, BN 465 BNS HAJI MOHSIN / Payra Port Authority / Chairman-PPA 18-09-2020 5 Cdre Mohammad Monirul Islam, (S), OSP, PCGMS, psc, BN 513 BNS HAJI MOHSIN / Defense and Strategic Studies Course, China 29-09-2020 6 Cdr Mohammad Shahed Karim, (C), BN 780 BNS HAJI MOHSIN / Embassy of Bangladesh / Asst Defense Attache-China 10/25/2020 7 Lt Cdr G Uttam Kumar, (SD)(R), BN 1722 BNS TITUMIR / MTO 10/30/2020 8 Cdre Abu Mohammad Quamrul Huq, (ND), NGP, ndc, afwc, psc, BN 473 BNS HAJI MOHSIN / Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Maritime University / Treasurer 01-12-2020 9 Cdre Sheikh Mahmudul Hassan, (H), NPP, aowc, psc, BN 539 BNS ISSA KHAN / CHO & BNHOC / Chief Hydrographer 31-12-2020 10 Capt Masuq Hassan Ahmed, (G), PPM, psc, BN 590 BNS ISSA KHAN / Marine Fisheries Academy / Principal 31-12-2020 11 Instr Cdr Sharif Mostafa Shamim, (G), BN 1372 BNS HAJI MOHSIN / NHQ/DNAI&S / Additional 01-01-2021 12 Cdr Mohammad Ismail, (S), BN 787 BNS SHEIKH MUJIB / ADMIN DHAKA / Principal- Anchorage 04-01-2021 13 Lt Cdr Ferdous -

The Threat from Jamaat-Ul Mujahideen Bangladesh

THE THREAT FROM JAMAAT-UL MUJAHIDEEN BANGLADESH Asia Report N°187 – 1 March 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 II. JMB BEFORE 2005.......................................................................................................... 2 A. SHAIKH ABDUR RAHMAN AND THE FOUNDING OF JMB.............................................................2 B. EARLY STRUCTURE....................................................................................................................4 C. RECRUITMENT ...........................................................................................................................5 D. ONE MAN’S RECRUITMENT........................................................................................................6 E. TRAINING ..................................................................................................................................6 F. FUNDING....................................................................................................................................8 G. OPERATIONS ..............................................................................................................................9 III. JMB AND THE BNP-JAMAAT GOVERNMENT..................................................... 10 IV. 2005-2007: THE 17 AUGUST BOMBINGS AND THE -

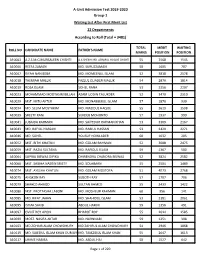

A-Unit Admission Test 2019-2020 Group-1 Waiting List After First Merit List 22 Departments According to Roll (Total = 3481)

A-Unit Admission Test 2019-2020 Group-1 Waiting List After First Merit List 22 Departments According to Roll (Total = 3481) TOTAL MERIT WAITING ROLL NO CANDIDATE NAME FATHER'S NAME MARKS POSITION POSITION A10003 A.Z.S.M.G.MURSALEEN CHISHTI A.A.SHEIKH MD. ASRARUL HOQUE CHISHTI 55 2568 1545 A10006 REEFA ZAMAN MD. SURUZZAMAN 58 1605 707 A10007 RIFAH NANJEEBA MD. MOMEENUL ISLAM 52 3818 2578 A10018 TASMIAH MALLIK FAZLUL QUADER MALLIK 54 2879 1814 A10019 ROZA ISLAM SOHEL RANA 53 3356 2207 A10023 MOHAMMAD MOOTASIM BILLAH AZAM UDDIN TALUKDER 52 3479 2310 A10029 MST. MITU AKTER MD. MONABBERUL ISLAM 57 1870 939 A10034 MD. SELIM MOSTAKIM MD. MAZIDUL HAQUE 55 2629 1598 A10039 SREETY RANI SUKDEB MOHONTO 57 1937 999 A10041 JUBAIDA RAHMAN MD. SAIYEDUR RAHMAN KHAN 53 3309 2167 A10043 MD. RAFIUL HASSAN MD. RABIUL HASSAN 53 3429 2271 A10046 MD. SOHEL YOUSUF HOWLADER 60 1032 205 A10052 MST. BITHI KHATUN MD. GOLAM RAHMAN 52 3688 2475 A10059 MST. RAZIA SULTANA MD. RAFIQUL ISLAM 59 1367 500 A10064 SUPRIA BISWAS DIPIKA DHIRENDRA CHANDRA BISWAS 52 3824 2582 A10066 MST. SABIHA NASRIN SRISTY MD. SOLAIMAN 55 2504 1489 A10074 MST. AYESHA KHATUN MD. GOLAM MOSTOFA 51 4073 2768 A10075 ANGKON RAY SUBOTH RAY 57 1707 796 A10079 SHAHED AHMED SULTAN AHMED 55 2433 1422 A10080 MST. PROTTASHA LABONI MD. MOSHEUR RAHMAN 60 956 141 A10085 MD. RIFAT JAHAN MD. SHAHIDUL ISLAM 53 3181 2061 A10095 ISTIAK SAKIB ABDUL HAKIM 59 1356 491 A10097 OVIJIT ROY APON BHAROT ROY 55 2614 1585 A10099 MOST. NASIFA AKTAR MD.