Immersion Emergence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Trajectory of a Struggle

SSHAHRIHAHRI AADHIKARDHIKAR MMANCH:ANCH: BBEGHARONEGHARON KKEE SSAATHAATH ((URBANURBAN RRIGHTSIGHTS FFORUM:ORUM: WWITHITH TTHEHE HHOMELESS)OMELESS) TTHEHE TTRAJECTORYRAJECTORY OOFF A SSTRUGGLETRUGGLE i Published by: Shahri Adhikar Manch: Begharon Ke Saath G-18/1 Nizamuddin West Lower Ground Floor New Delhi – 110 013 +91-11-2435-8492 [email protected] Text: Jaishree Suryanarayan Editing: Shivani Chaudhry and Indu Prakash Singh Design and printing: Aspire Design March 2014, New Delhi Printed on CyclusPrint based on 100% recycled fibres SSHAHRIHAHRI AADHIKARDHIKAR MMANCH:ANCH: BBEGHARONEGHARON KKEE SSAATHAATH ((URBANURBAN RRIGHTSIGHTS FFORUM:ORUM: WWITHITH TTHEHE HHOMELESS)OMELESS) TTHEHE TTRAJECTORYRAJECTORY OOFF A SSTRUGGLETRUGGLE Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Objective and Methodology of this Study 2 2. BACKGROUND 3 2.1 Defi nition and Extent of Homelessness in Delhi 3 2.2 Human Rights Violations Faced by Homeless Persons 5 2.3 Criminalisation of Homelessness 6 2.4 Right to Adequate Housing is a Human Right 7 2.5 Past Initiatives 7 3. FORMATION AND GROWTH OF SHAHRI ADHIKAR MANCH: BEGHARON KE SAATH 10 3.1 Formation of Shahri Adhikar Manch: Begharon Ke Saath (SAM:BKS) 10 3.2 Vision and Mission of SAM:BKS 11 3.3 Functioning of SAM:BKS 12 4. STRATEGIC INTERVENTIONS 14 4.1 Strategies Used by SAM:BKS 14 4.2 Intervention by SAM:BKS in the Suo Moto Case in the High Court of Delhi 16 4.3 Media Advocacy 19 4.4 Campaigns of SAM:BKS for Facilitating Access to Entitlements and Realisation of Human Rights 20 5. THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA AND THE ISSUE OF HOMELESSNESS 22 5.1 Role of the Offi ce of Supreme the Court Commissioners in the ‘Right to Food’ Case 22 6. -

Slum Rehabilitation in Delhi

WHOSE CITY IS IT ANYWAY? KRISHNA RAJ FELLOWSHIP PROJECT Madhulika Khanna, Keshav Maheshwari, Resham Nagpal, Ravideep Sethi, Sandhya Srinivasan August 2011 Delhi School of Economics 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank our professor, Dr. Anirban Kar, who gave direction to our research and coherence to our ideas. We would like to express our gratitude towards Mr. Dunu Roy and everyone at the Hazards Centre for their invaluable inputs. We would also like to thank all our respondents for their patience and cooperation. We are grateful to the Centre for Development Economics, Delhi School of Economics for facilitating our research. CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 1 2. POLICY FRAMEWORK ...................................................................................................................... 2 2.1. SLUM POLICY IN DELHI ............................................................................................................ 2 2.2. SLUM REHABILITATION PROCESS ........................................................................................... 4 2.2.1. IN-SITU UP-GRADATION .................................................................................................. 4 2.2.2. RELOCATION.................................................................................................................... 4 3. RIGHTS AND CITIZENSHIP ............................................................................................................... -

The Challenge of “Human” Sustainability for Indian Mega-Cities: Squatter Settlements, Forced Evictions and Resettlement & Rehabilitation Policies in Delhi

V. Dupont Do not quote without the author’s permission Paper presented to: XXVII IUSSP International Population Conference Busan, Corea, 26-31 August 2013 Session 282: The sustainability of mega-cities The challenge of “human” sustainability for Indian mega-cities: Squatter settlements, forced evictions and resettlement & rehabilitation policies in Delhi Véronique Dupont Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (Institute of Research for Development) Email: [email protected] Abstract This paper deals with the “human” dimension of sustainability in Indian mega-cities, specially the issue of social equity approached through the housing requirements of the urban poor. Indian mega-cities are faced with an acute shortage in adequate housing, which has resulted in the growth of illegal slums or squatter settlements. Since the 1990s, the implementation of urban renewal projects, infrastructure expansion and “beautification” drives, in line with the requirements of globalising cities, have resulted in many slum demolitions, which increased the numbers of homeless people. Delhi exemplifies such trends. This paper’s main objective is to appraise the adequacy of slum clearance and resettlement and rehabilitation policies implemented in Delhi in order to address the challenge of slums. Do such policies alleviate the problem of lack of decent housing for the urban poor, or to what extent do they also aggravate their situation? It combines two approaches: firstly, a statistical assessment of squatters’ relocation and slum demolition without resettlement over the last two decades, completed by an analysis of the conditions of implementation of the resettlement policy; and, secondly, a qualitative and critical analysis of the recently launched strategy of in-situ rehabilitation under public- private partnership. -

Public Interest Litigation and Political Society in Post-Emergency India

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Columbia University Academic Commons Competing Populisms: Public Interest Litigation and Political Society in Post-Emergency India Anuj Bhuwania Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2013 © 2013 Anuj Bhuwania All rights reserved ABSTRACT Competing Populisms: Public Interest Litigation and Political Society in Post-Emergency India Anuj Bhuwania This dissertation studies the politics of ‘Public Interest Litigation’ (PIL) in contemporary India. PIL is a unique jurisdiction initiated by the Indian Supreme Court in the aftermath of the Emergency of 1975-1977. Why did the Court’s response to the crisis of the Emergency period have to take the form of PIL? I locate the history of PIL in India’s postcolonial predicament, arguing that a Constitutional framework that mandated a statist agenda of social transformation provided the conditions of possibility for PIL to emerge. The post-Emergency era was the heyday of a new form of everyday politics that Partha Chatterjee has called ‘political society’. I argue that PIL in its initial phase emerged as its judicial counterpart, and was even characterized as ‘judicial populism’. However, PIL in its 21 st century avatar has emerged as a bulwark against the operations of political society, often used as a powerful weapon against the same subaltern classes whose interests were so loudly championed by the initial cases of PIL. In the last decade, for instance, PIL has enabled the Indian appellate courts to function as a slum demolition machine, and a most effective one at that – even more successful than the Emergency regime. -

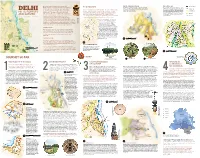

JOURNEY SO FAR of the River Drain Towards East Water

n a fast growing city, the place of nature is very DELHI WITH ITS GEOGRAPHICAL DIVISIONS DELHI MASTER PLAN 1962 THE REGION PROTECTED FOREST Ichallenging. On one hand, it forms the core framework Based on the geology and the geomorphology, the region of the city of Delhi The first ever Master plan for an Indian city after independence based on which the city develops while on the other can be broadly divided into four parts - Kohi (hills) which comprises the hills of envisioned the city with a green infrastructure of hierarchal open REGIONAL PARK Spurs of Aravalli (known as Ridge in Delhi)—the oldest fold mountains Aravalli, Bangar (main land), Khadar (sandy alluvium) along the river Yamuna spaces which were multi functional – Regional parks, Protected DELHI hand, it faces serious challenges in the realm of urban and Dabar (low lying area/ flood plains). greens, Heritage greens, and District parks and Neighborhood CULTIVATED LAND in India—and river Yamuna—a tributary of river Ganga—are two development. The research document attempts to parks. It also included the settlement of East Delhi in its purview. HILLS, FORESTS natural features which frame the triangular alluvial region. While construct a perspective to recognize the role and value Moreover the plan also suggested various conservation measures GREENBELT there was a scattering of settlements in the region, the urban and buffer zones for the protection of river Yamuna, its flood AND A RIVER of nature in making our cities more livable. On the way, settlements of Delhi developed, more profoundly, around the eleventh plains and Ridge forest. -

A River and the Riverfront: Delhi's Yamuna As an In-Between Space

ARTICLE IN PRESS City, Culture and Society ■■ (2015) ■■–■■ Contents lists available at ScienceDirect City, Culture and Society journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ccs A river and the riverfront: Delhi’s Yamuna as an in-between space Awadhendra Sharan * Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, 29, Rajpur Road, Delhi 110054, India ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: This essay examines the presence of Yamuna in the city of Delhi, from two perspectives: (i) understand- Available online ing riverscapes as simultaneously aquatic and terrestrial and (ii) understanding these as conjoining issues of environment and technology. With events over the course of the last century as its backdrop, the essay Keywords: focuses on the last few decades of the twentieth century, to examine the relation of land and river in Yamuna Delhi; the interface of people and projects, especially the issue of slums; and the risks posed to the river Pollution on account of waste and pollution. All these featured prominently in the events leading up to the staging River of the Commonwealth Games in Delhi in October 2010, which provides the most immediate context for Nature Sustainability this essay. In conclusion, I propose that the current strategies of rejuvenating the river are limited, often Planning anti-poor and far from sustainable. © 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Introduction elsewhere, was a means to brand the city and to manufacture solidarities around an urban place ‘by Over the last decade and more Delhi aspired to imbuing it with an affective charge, a structure of transit from a ‘walled city’ to a ‘world city’.1 In the feeling that is generated by the scale, compression process, it attempted, or at least its elite groups en- and celebratory content of the event itself’ (Baviskar, deavoured, to reshape spatial arrangements, 2011b). -

HOMELESSNESS ABOUT BUTTERFLIES Children in News Homelessness

HOMELESSNESS ABOUT BUTTERFLIES Children in News Homelessness VOL. XXIV, 2015 HIS NAME IS TODAY Years V 1989 -2014 OL. XXIV , 2015 U-4, Green Park Extension, New Delhi-110016 CHILDREN IN NEWS VOL XXIV, 2015 1 Tel.: 26163935, 26191063 E-mail: [email protected] Delhi Child Rights Club The Delhi Child Rights Club (DCRC) was launched by BUTTERFLIES in 1998. There was a need to have a children's forum in Delhi where children could articulate their issues and collectively take action to get their entitlements which is rightfully theirs. BUTTERFLIES invited children of NGOs working with children based in Delhi to be part of this forum. The response to this invitation was encouraging. Today there are children from 15 NGOs who are members In the little world in which and in recent times children from various neighbourhoods have attended DCRC meetings. The primary objective of DCRC is to have children's voices heard by civil society and policy makers, their views on issues children have their existence pertaining to their lives be taken seriously, and to consult them on all issues related to their welfare, development and protection. DCRC is open to all children of Delhi under 18 years of age whether from working whosoever brings them up,there is class, middle class or upper class background or a child living in an institution. A city-wide Child Rights Club is one mechanism where by children can work together towards the creation of a child safe and nothing so finely perceived and so friendly city. The children envisage a city where children's rights to respect, dignity, opportunities, growth, development and protection are ensured. -

Pavement Dwelling in Delhi, India: an Ethnographic Account of Survival on the Margins Deborah K

Human Organization, Vol. 76, No. 1, 2017 Copyright © 2017 by the Society for Applied Anthropology 0018-7259/17/010073-09$1.40/1 Pavement Dwelling in Delhi, India: An Ethnographic Account of Survival on the Margins Deborah K. Padgett and Prachi Priyam This article examines survival among homeless persons (“pavement dwellers”) in Delhi, India. In particular, we explore the role of formal and informal relationships in meeting the demands of daily existence and how and when public social welfare programs assist pavement dwellers. Over fifteen months, beginning in 2013, participant observation was conducted, and approximately 200 individuals (homeless persons, government officials, and NGO representatives) were interviewed in Hindi or English. Triangulated data including documents, interviews, and fieldnotes were subjected to thematic analyses. Results produced five themes: persistent illegality, dependence on charitable others, personhood and worthiness, migration and social isolation, and precarious relationships and distrust. Based on the research findings, we make recommendations for legal inclusion, decriminalization, access to health care, and income support for parents with dependent children. Broader concerns about global homelessness are also discussed in the context of growing income inequality. Key words: homelessness, Global South, stigma, income inequality Introduction United States, Canada, and Western Europe, Hojdestrand’s (2009) research in St. Petersburg, Russia, examines the plight he worldwide problem of inadequate housing is espe- of homeless adults consigned to the margins of post-socialist cially evident in low-income countries where the status Russian society. Marr (2015) took a cross-national approach in of being homeless could arguably include millions his description of adults exiting homelessness in Los Angeles T and Tokyo. -

Forced Evictions and the 2010 Commonwealth Games Report of A

Forced Evictions and the 2010 Commonwealth Games Fact- finding e Housing and Land Rights Network (HLRN) is an integral part of the Habitat International Coalition (HIC) - Mission an independent, international, non-prot movement of over 450 members specialised in various aspects of human settlements. Members include NGOs, social movements, academic and research institutions, professional associations Planned Report and like-minded individuals from 80 countries in both the North and South, all dedicated to the realisation of the human right to adequate housing for everyone. 14 HLRN seeks to advocate for the recognition, defence and full implementation of everyone’s human right to a secure Dispossession place to live in peace and dignity, by: Promoting public awareness about human settlement problems and needs globally; Forced Evictions and the 2010 Commonwealth Games Cooperating with UN human rights bodies to develop and monitor standards of the human right to adequate housing, as well as clarify states’ obligations to respect, protect, promote and full the right; Defending the human rights of the homeless and inadequately housed; Upholding legal protection of the human right to adequate housing; Providing a common platform to formulate strategies through social movements and progressive NGOs; and, Advocating on their behalf in international forums. To attain these objectives, HLRN member services include: Building local, regional and international member cooperation to form eective housing and land rights campaigns; Human resource development, human rights education and training; Action research, fact-nding, and publication; Exchanging and disseminating member experiences, best practices and strategies; Advocacy and lobbying; Developing tools and techniques for professional monitoring of housing and land rights; and, Urgent actions against forced evictions and other housing and land rights violations. -

Commonwealth Games 2010 and Use of the Facilities After the Games

Commonwealth Games 2010 and Use of the facilities after the Games A business of hope Submitted to Centre for Civil Society By Maina Sharma Working Paper No 214 Summer Research Internship 2009 CONTENTS I. Abstract……………………………………………………….. 3 II. Introduction………………………………………………….. 5 III. Commonwealth Games 2010: Overview……………… 7 1. Facilities…………………………………………………….. 1.1 Sporting…………………………………………… 1.2 Non- Sporting……………………………………. 1.3 Games Village……………………………………. 2. Key Stakeholders………………………………………….. IV. Impact on Various Sectors……………………………… 20 V. Recommendations………………………………………… 28 VI. Conclusion………………………………………………….. 38 References 40 Centre for Civil Society 2 I. ABSTRACT It was called Great Britain because of its rich history, of having ruled over infinite masses all across the globe under the crown of the British Empire. This great empire organised an inter-colony sporting event, which after many years, came to be known by the name of The Commonwealth Games. Now, after 22 years, New Delhi, the capital city of India has won the bid for organising the 9th Commonwealth Games in the year 2010. It follows, then, that like any other host country, India is in the proc- ess of investing a great amount of effort in putting together this hallmark event, and is determined to make a favourable mark on the global scene. However, the ques- tion then arises of whether the city is prepared enough to organise such an event. Also in what different ways does it hope to benefit from this international contest? After spending a huge amount of time and money in preparing -

River Yamuna: Deteriorating Water Quality & Its Socio-Economic Impact

River Yamuna: Deteriorating Water Quality & its Socio-economic Impact JULY 2020 Tata Centre for Development The Tata Centre for Development (TCD) at the University of Chicago works to identify novel solutions to India’s most pressing development challenges and to ensure that these ideas are translated into outcomes that improve people’s lives. Launched in 2016 with generous support from the Tata Trusts, TCD follows a unique approach that harnesses evidence-based insights from UChicago’s rigorous economics research. An affi liated Centre of the Becker Friedman Institute for Economics at UChicago, TCD upholds the university’s tradition of applying economic thinking to a wide range of social challenges and advancing important research on India through a convergence of scholars from across disciplines. To translate research insights into policy action, TCD engages with policymakers at all levels of government and policy entrepreneurs across sectors and launches pilot projects to demonstrate success. Representing the joint work of the Tata Trusts and the University of Chicago, TCD asks diffi cult questions, challenges conventional thinking, and creates a new model for impact in India. Water-to-Cloud (W2C) Water-to-Cloud is an initiative housed under Tata Centre for Development to map water quality over large water bodies using in-situ cyber-physical systems. It aims to create a repository of reliable water quality data from rivers across India with the belief that putting out such comprehensive and actionable data in the public domain can lead to positive action to improve the health of our water bodies. So far over 300,000 water quality data points have been collected across 11 sites on the 4 major Indian rivers and some lakes since 2016. -

Yamuna Pushta.Pmd

I. Introduction The Delhi landscape is distinctive among Indian and other ‘third world’ megacities. The heavy impact of state policies has been evident for a long while. Today, state policies are in a “India Shining” distinctive new phase. A new, socially sanitized Delhi of ‘international standards’, of expressways and flyovers, Commonwealth games villages, places of exorbitant consumption, and landscaped Yamuna riverfronts, is in the making. Part of this state-sponsored redevelopment of the city requires suddenly ousting lakhs of slum-dwellers and not rehabilitating them. The latest to come under attack are the countless people staying in and around the riverfront in Yamuna Pushta, with the police, the courts, urban development agencies having decided to dispense with their lives and livelihood. Of course, demolitions and ‘resettlements’ have been A Report On standard fare for Delhi’s slum-dwellers, most notoriously during the Emergency in1975. In terms of the violation of people’s rights, Demolition and Resettlement of the Yamuna Pushta demolitions are therefore not unique. And yet they must be seen not merely as repetitions of earlier demolition Yamuna Pushta Bastis episodes but also as part of a recently renewed and intensified state commitment to the branding, upgrading and gentrification of the city. In the third and fourth weeks of April, amid media silence, PUDR conducted a fact-finding into the demolitions at Yamuna- Pushta and into the displacement of people to verify the government’s claim of a lawful, orderly and tranquil relocation. The arrests of residents, two fires in quick succession, and the plight of men, women and children forced to live without a roof under the blazing summer sun made for the urgency in releasing our findings to the press and in petitioning state authorities.