Forced Evictions and the 2010 Commonwealth Games Report of A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Trajectory of a Struggle

SSHAHRIHAHRI AADHIKARDHIKAR MMANCH:ANCH: BBEGHARONEGHARON KKEE SSAATHAATH ((URBANURBAN RRIGHTSIGHTS FFORUM:ORUM: WWITHITH TTHEHE HHOMELESS)OMELESS) TTHEHE TTRAJECTORYRAJECTORY OOFF A SSTRUGGLETRUGGLE i Published by: Shahri Adhikar Manch: Begharon Ke Saath G-18/1 Nizamuddin West Lower Ground Floor New Delhi – 110 013 +91-11-2435-8492 [email protected] Text: Jaishree Suryanarayan Editing: Shivani Chaudhry and Indu Prakash Singh Design and printing: Aspire Design March 2014, New Delhi Printed on CyclusPrint based on 100% recycled fibres SSHAHRIHAHRI AADHIKARDHIKAR MMANCH:ANCH: BBEGHARONEGHARON KKEE SSAATHAATH ((URBANURBAN RRIGHTSIGHTS FFORUM:ORUM: WWITHITH TTHEHE HHOMELESS)OMELESS) TTHEHE TTRAJECTORYRAJECTORY OOFF A SSTRUGGLETRUGGLE Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Objective and Methodology of this Study 2 2. BACKGROUND 3 2.1 Defi nition and Extent of Homelessness in Delhi 3 2.2 Human Rights Violations Faced by Homeless Persons 5 2.3 Criminalisation of Homelessness 6 2.4 Right to Adequate Housing is a Human Right 7 2.5 Past Initiatives 7 3. FORMATION AND GROWTH OF SHAHRI ADHIKAR MANCH: BEGHARON KE SAATH 10 3.1 Formation of Shahri Adhikar Manch: Begharon Ke Saath (SAM:BKS) 10 3.2 Vision and Mission of SAM:BKS 11 3.3 Functioning of SAM:BKS 12 4. STRATEGIC INTERVENTIONS 14 4.1 Strategies Used by SAM:BKS 14 4.2 Intervention by SAM:BKS in the Suo Moto Case in the High Court of Delhi 16 4.3 Media Advocacy 19 4.4 Campaigns of SAM:BKS for Facilitating Access to Entitlements and Realisation of Human Rights 20 5. THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA AND THE ISSUE OF HOMELESSNESS 22 5.1 Role of the Offi ce of Supreme the Court Commissioners in the ‘Right to Food’ Case 22 6. -

Slum Rehabilitation in Delhi

WHOSE CITY IS IT ANYWAY? KRISHNA RAJ FELLOWSHIP PROJECT Madhulika Khanna, Keshav Maheshwari, Resham Nagpal, Ravideep Sethi, Sandhya Srinivasan August 2011 Delhi School of Economics 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank our professor, Dr. Anirban Kar, who gave direction to our research and coherence to our ideas. We would like to express our gratitude towards Mr. Dunu Roy and everyone at the Hazards Centre for their invaluable inputs. We would also like to thank all our respondents for their patience and cooperation. We are grateful to the Centre for Development Economics, Delhi School of Economics for facilitating our research. CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 1 2. POLICY FRAMEWORK ...................................................................................................................... 2 2.1. SLUM POLICY IN DELHI ............................................................................................................ 2 2.2. SLUM REHABILITATION PROCESS ........................................................................................... 4 2.2.1. IN-SITU UP-GRADATION .................................................................................................. 4 2.2.2. RELOCATION.................................................................................................................... 4 3. RIGHTS AND CITIZENSHIP ............................................................................................................... -

The Challenge of “Human” Sustainability for Indian Mega-Cities: Squatter Settlements, Forced Evictions and Resettlement & Rehabilitation Policies in Delhi

V. Dupont Do not quote without the author’s permission Paper presented to: XXVII IUSSP International Population Conference Busan, Corea, 26-31 August 2013 Session 282: The sustainability of mega-cities The challenge of “human” sustainability for Indian mega-cities: Squatter settlements, forced evictions and resettlement & rehabilitation policies in Delhi Véronique Dupont Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (Institute of Research for Development) Email: [email protected] Abstract This paper deals with the “human” dimension of sustainability in Indian mega-cities, specially the issue of social equity approached through the housing requirements of the urban poor. Indian mega-cities are faced with an acute shortage in adequate housing, which has resulted in the growth of illegal slums or squatter settlements. Since the 1990s, the implementation of urban renewal projects, infrastructure expansion and “beautification” drives, in line with the requirements of globalising cities, have resulted in many slum demolitions, which increased the numbers of homeless people. Delhi exemplifies such trends. This paper’s main objective is to appraise the adequacy of slum clearance and resettlement and rehabilitation policies implemented in Delhi in order to address the challenge of slums. Do such policies alleviate the problem of lack of decent housing for the urban poor, or to what extent do they also aggravate their situation? It combines two approaches: firstly, a statistical assessment of squatters’ relocation and slum demolition without resettlement over the last two decades, completed by an analysis of the conditions of implementation of the resettlement policy; and, secondly, a qualitative and critical analysis of the recently launched strategy of in-situ rehabilitation under public- private partnership. -

Public Interest Litigation and Political Society in Post-Emergency India

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Columbia University Academic Commons Competing Populisms: Public Interest Litigation and Political Society in Post-Emergency India Anuj Bhuwania Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2013 © 2013 Anuj Bhuwania All rights reserved ABSTRACT Competing Populisms: Public Interest Litigation and Political Society in Post-Emergency India Anuj Bhuwania This dissertation studies the politics of ‘Public Interest Litigation’ (PIL) in contemporary India. PIL is a unique jurisdiction initiated by the Indian Supreme Court in the aftermath of the Emergency of 1975-1977. Why did the Court’s response to the crisis of the Emergency period have to take the form of PIL? I locate the history of PIL in India’s postcolonial predicament, arguing that a Constitutional framework that mandated a statist agenda of social transformation provided the conditions of possibility for PIL to emerge. The post-Emergency era was the heyday of a new form of everyday politics that Partha Chatterjee has called ‘political society’. I argue that PIL in its initial phase emerged as its judicial counterpart, and was even characterized as ‘judicial populism’. However, PIL in its 21 st century avatar has emerged as a bulwark against the operations of political society, often used as a powerful weapon against the same subaltern classes whose interests were so loudly championed by the initial cases of PIL. In the last decade, for instance, PIL has enabled the Indian appellate courts to function as a slum demolition machine, and a most effective one at that – even more successful than the Emergency regime. -

Success on the World Stage Athletics Australia Annual Report 2010–2011 Contents

Success on the World Stage Athletics Australia Annual Report Success on the World Stage Athletics Australia 2010–2011 2010–2011 Annual Report Contents From the President 4 From the Chief Executive Officers 6 From The Australian Sports Commission 8 High Performance 10 High Performance Pathways Program 14 Competitions 16 Marketing and Communications 18 Coach Development 22 Running Australia 26 Life Governors/Members and Merit Award Holders 27 Australian Honours List 35 Vale 36 Registration & Participation 38 Australian Records 40 Australian Medalists 41 Athletics ACT 44 Athletics New South Wales 46 Athletics Northern Territory 48 Queensland Athletics 50 Athletics South Australia 52 Athletics Tasmania 54 Athletics Victoria 56 Athletics Western Australia 58 Australian Olympic Committee 60 Australian Paralympic Committee 62 Financial Report 64 Chief Financial Officer’s Report 66 Directors’ Report 72 Auditors Independence Declaration 76 Income Statement 77 Statement of Comprehensive Income 78 Statement of Financial Position 79 Statement of Changes in Equity 80 Cash Flow Statement 81 Notes to the Financial Statements 82 Directors’ Declaration 103 Independent Audit Report 104 Trust Funds 107 Staff 108 Commissions and Committees 109 2 ATHLETICS AuSTRALIA ANNuAL Report 2010 –2011 | SuCCESS ON THE WORLD STAGE 3 From the President Chief Executive Dallas O’Brien now has his field in our region. The leadership and skillful feet well and truly beneath the desk and I management provided by Geoff and Yvonne congratulate him on his continued effort to along with the Oceania Council ensures a vast learn the many and numerous functions of his array of Athletics programs can be enjoyed by position with skill, patience and competence. -

Immersion Emergence

immersion emergence ISBN 81-7525-751-2 ravi agarwal immersion emergence the shroud : self-portrait ravi agarwal April 27, 2006 Copyright © 2006 by Ravi Agarwal All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy- ing, recording, or by any form of information storage and retireval system, without permission in writing fromt e publisher. Published by Ravi Agarwal, New Delhi, India. E-mail [email protected] to order copies. Price: Rs 300 (India) / USD 25 (international); postage at actuals Printed in India by Ajanta Offset & Packagings Limited ISBN xxx To my parents Acknowledgements To the river waters, who let me in. To those who live on and around it. To my friends, family and colleagues, who were there at my asking, some all the while, some who joined along the way, or had to leave, even as I came and went. Nanni, Bharat, Aniruddha and Anjali, Salil and Monika, Amit, Jeebesh, Sveta, Monica, Rana, Shuddha, Dorothea, Sonia, Gauri, Gayatri, Bina, Sharda, Alka, Reena. To Ritika and to Anand, who directly participated in and helped deepen my explorations. To Geeti Sen for my first river writing. To my colleagues and friends at Toxics Link who accepted me on my own terms. To Cdr. Siddeshwar Sinha and Dunu Roy, who graciously shared their knowledge about the river. To Jeebesh for forever unfailingly showing my mind a light. To Naintara for patiently shooting me in “The Shroud”. To Aniruddha and Salil for lovingly designing and producing this. To my elusive inseparable Varda. -

Commonwealth Games INTRODUCTION the Next Commonwealth Games Are Going to Be Held in 2010 in New Delhi, the Capital of Our Country

Yuva for All Session 3.11 TITLE : Looking forward to the Commonwealth Games INTRODUCTION The next Commonwealth Games are going to be held in 2010 in New Delhi, the capital of our country. This session ai ms at preparing students to be good hosts and volunteers during the Games. It aims at enhancing life skills such as Self Awareness, Creative and Critical Thinking, Empathy, Effective Communication and improving Inter-Personal Relationships with people from other countries. 1. Objectives : By the end of the session, the students will be able to Become aware about the Commonwealth and Commonwealth Games. Become aware about the importance of events such as the Commonwealth Games. Understand the importance of extending warmth, hospitality and cooperation to the guests from other countries who visit Delhi in relation with the Games. 2. Time : 70 Minutes (Two continuous periods) 3. Life Skills Being Used : Effective Communication, Decision Making, Empathy, Problem Solving, Critical Thinking 4. Advance Preparations : None 5. Linkages : Please see Contents 6. Methodology : Group Discussion, Role play 7. Process : Step 1: Please read the Fact Sheet carefully, and go through this session well in advance before you carry it out with the students. YUVA Help Line No. 1800116888 1 Step 2: Greet the class and state that we all know that Delhi is going to host the Commonwealth Games in 2010. All agencies are working fulltime to prepare for the Games. The roads are being widened, and venues for the games are being spruced up. A whole new setup for the stay of the athletes –the “Commonwealth Games Village” - is coming up near the Akshardham temple. -

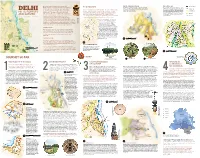

JOURNEY SO FAR of the River Drain Towards East Water

n a fast growing city, the place of nature is very DELHI WITH ITS GEOGRAPHICAL DIVISIONS DELHI MASTER PLAN 1962 THE REGION PROTECTED FOREST Ichallenging. On one hand, it forms the core framework Based on the geology and the geomorphology, the region of the city of Delhi The first ever Master plan for an Indian city after independence based on which the city develops while on the other can be broadly divided into four parts - Kohi (hills) which comprises the hills of envisioned the city with a green infrastructure of hierarchal open REGIONAL PARK Spurs of Aravalli (known as Ridge in Delhi)—the oldest fold mountains Aravalli, Bangar (main land), Khadar (sandy alluvium) along the river Yamuna spaces which were multi functional – Regional parks, Protected DELHI hand, it faces serious challenges in the realm of urban and Dabar (low lying area/ flood plains). greens, Heritage greens, and District parks and Neighborhood CULTIVATED LAND in India—and river Yamuna—a tributary of river Ganga—are two development. The research document attempts to parks. It also included the settlement of East Delhi in its purview. HILLS, FORESTS natural features which frame the triangular alluvial region. While construct a perspective to recognize the role and value Moreover the plan also suggested various conservation measures GREENBELT there was a scattering of settlements in the region, the urban and buffer zones for the protection of river Yamuna, its flood AND A RIVER of nature in making our cities more livable. On the way, settlements of Delhi developed, more profoundly, around the eleventh plains and Ridge forest. -

3.8 Malpractice in the 2010 Delhi Commonwealth Games and the Renovation Of

This content is drawn from Transparency International’s forthcoming Global Corruption Report: Sport. For more information on our Corruption in Sport Initiative, visit: www.transparency.org/sportintegrity 3.8 Malpractice in the 2010 Delhi Commonwealth Games and the renovation of Shivaji Stadium Ashutosh Kumar Mishra1 The 2010 Commonwealth Games, held in New Delhi, were marred by allegations of corruption and mismanagement, which tarnished the image of India by presenting it as a country blighted by high levels of fraud and malpractice.2 From the very beginning the event was shrouded in controversies, which continually surfaced and have still not been fully resolved. Concerns were raised during the preparatory phase, with construction work falling behind schedule and volunteers quitting in large numbers because of dissatisfaction with their assignments and with the training programme. Gross violations of workers’ rights were reported at construction sites, where workers were forced into begar.3 The conclusion of the Games brought to the fore further issues, such as the reported flouting of contracting rules by officials of the Organising Committee and the awarding of work contracts to incompetent agencies at hugely inflated prices.4 At the start it was not clear whether the Organising Committee would be covered under the national Right to Information (RTI) Act, as it did not come under the purview of the definition of ‘state’.5 Such grey areas can create a sense of immunity from rules, procedures and accountability. Concerns about the management -

Nswis Annual Report 2010/2011

nswis annual report 2010/2011 NSWIS Annual Report For further information on the NSWIS visit www.nswis.com.au NSWIS a GEOFF HUEGILL b NSWIS For further information on the NSWIS visit www.nswis.com.au nswis annual report 2010/2011 CONtENtS Minister’s Letter ............................................................................... 2 » Bowls ...................................................................................................................41 Canoe Slalom ......................................................................................................42 Chairman’s Message ..................................................................... 3 » » Canoe Sprint .......................................................................................................43 CEO’s Message ................................................................................... 4 » Diving ................................................................................................................. 44 Principal Partner’s Report ......................................................... 5 » Equestrian ...........................................................................................................45 » Golf ......................................................................................................................46 Board Profiles ..................................................................................... 6 » Men’s Artistic Gymnastics .................................................................................47 -

Commonwealth Games Canada Alumni Newsletter - November 2019 / Jeux Du Commonwealth Canada Communiqué Des Anciens - Novembre 2019

Commonwealth Games Canada Alumni Newsletter - November 2019 / Jeux du Commonwealth Canada Communiqué des anciens - novembre 2019 Subscribe Past Issues Translate RSS (le français à suivre) View this email in your browser Commonwealth Games Canada ALUMNI COMMUNIQUE Issue 6 - November 2019 HAVE YOU JOINED COMMONWEALTH GAMES CANADA'S ALUMNI PROGRAM YET? To date, approximately 3,000 Canadian athletes have competed in the Commonwealth Games. Thousands more have attended the Games as officials or given their time as volunteers. Over 200 CGC SportWORKS Officers have taken part in sport development initiatives in Canada and throughout the Commonwealth. CGC is proud to have been a part of so many lives and we would cherish the opportunity to continue our relationship through the CGC Alumni Program! Why should you become a CGC Alumni Program member? Being a CGC Alumni Program member allows you to: Stay in touch with other CGC alumni. Receive regular CGC Alumni Newsletters containing news & information about the Commonwealth sport movement in Canada and abroad. Become a mentor and contribute to the success of current and future CGC alumni. Receive invitations to CGC Alumni events happening in your area. Receive exclusive access and offers on CGC/Team Canada clothing, Commonwealth sport events tickets and packages, etc. Have a chance to win an all-inclusive, VIP trip for two to the next Commonwealth Games! Receive exclusive CGC Alumni discounts! As a Commonwealth Games Canada Alumni Program member, you are entitled to the following discounts: 20% DISCOUNT AT ALL RUNNING ROOM STORES REMINDER: If you are a CGC Alumni Program member and have not yet received your Running Room discount card, please confirm your mailing address so we can send it to you. -

A River and the Riverfront: Delhi's Yamuna As an In-Between Space

ARTICLE IN PRESS City, Culture and Society ■■ (2015) ■■–■■ Contents lists available at ScienceDirect City, Culture and Society journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ccs A river and the riverfront: Delhi’s Yamuna as an in-between space Awadhendra Sharan * Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, 29, Rajpur Road, Delhi 110054, India ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: This essay examines the presence of Yamuna in the city of Delhi, from two perspectives: (i) understand- Available online ing riverscapes as simultaneously aquatic and terrestrial and (ii) understanding these as conjoining issues of environment and technology. With events over the course of the last century as its backdrop, the essay Keywords: focuses on the last few decades of the twentieth century, to examine the relation of land and river in Yamuna Delhi; the interface of people and projects, especially the issue of slums; and the risks posed to the river Pollution on account of waste and pollution. All these featured prominently in the events leading up to the staging River of the Commonwealth Games in Delhi in October 2010, which provides the most immediate context for Nature Sustainability this essay. In conclusion, I propose that the current strategies of rejuvenating the river are limited, often Planning anti-poor and far from sustainable. © 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Introduction elsewhere, was a means to brand the city and to manufacture solidarities around an urban place ‘by Over the last decade and more Delhi aspired to imbuing it with an affective charge, a structure of transit from a ‘walled city’ to a ‘world city’.1 In the feeling that is generated by the scale, compression process, it attempted, or at least its elite groups en- and celebratory content of the event itself’ (Baviskar, deavoured, to reshape spatial arrangements, 2011b).